Doing business in China, from a cultural perspective

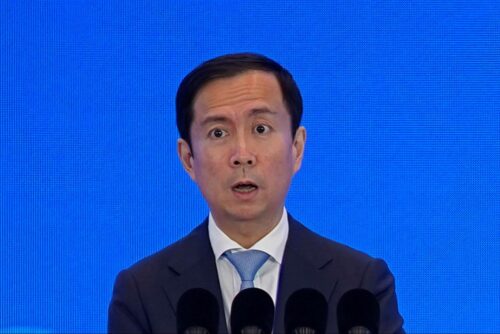

Mona Chung, a bicultural business leader, discusses some of the cultural challenges and strategies that foreign companies face when doing business in China.

Below is a complete transcript of the China Corner Office Podcast with Mona Chung.

Chris: Hi everyone. Thanks so much for joining us today on China Corner Office, a podcast powered by The China Project, the New York-based news and information platform that helps the West reach China between the lines. I’m Chris Marquis, a professor at the Cambridge Judge Business School. And today, we are joined by Mona Chung, a bicultural expert on doing business in and with China. After getting her PhD, Mona was a professor at Deakin University in Australia, and most recently joined BlueMount Capital, a consulting firm advising international businesses in China.

We started our conversation exploring Mona’s academic career and her dissertation and subsequent book that focused on Foster’s, the Australian beer company, and the company’s failed market entry. Mona shared her research on how a lack of awareness and understanding of cultural differences undermined Foster’s work in China from the start. She told me many interesting, and sometimes funny stories of cultural misunderstanding such as translation of the brand name, preferences of beer types and temperature, and also pricing strategies. We then moved on to discuss some of the common cultural differences that might create tensions between Chinese and foreign businesses, especially in areas like marketing and cross-cultural management.

With this in mind, we also discussed Mona’s work at BlueMount Capital and the challenges her clients face. She shared some useful cultural communications and negotiation strategies that helped one of her clients, an Australian wagyu exporter navigate the China market, especially during the pandemic when face-to-face communications are becoming even harder to realize. Mona has also written extensively on Huawei. And we also discussed Rèn Zhèngfēi’s 任正非 recent memo addressing Huawei employees that paints a gloomy picture of the company’s future. Mona shared her thoughts also on Ren’s army connections and the nature of the relationship between the Chinese Communist Party and Chinese companies.

Also covered in our conversation is the lasting importance of Maoism in China and how Máo [Zédōng 毛泽东] fundamentally changed Chinese society. Mona gives credits to Mao for elevating women’s positions, of course embodied in the famous quote, “Women hold up half the sky.” But she also pointed out that the Cultural Revolution planted seeds of distrust in China’s relationship-based society, which makes communications even more important when doing business. We concluded with Mona giving three valuable suggestions to Western companies wishing to enter the China market in today’s tense climate.

Thank you so much for listening and enjoy the show.

Chris: Mona, welcome to China Corner Office.

Mona: Chris, thank you very much for having me.

Chris: The first question, I’d love to dive in a little bit about your research on Foster’s beverage in China. You have this really evocatively titled book called Shanghaied: why Foster’s could not survive China. One of the reasons why I think that’s appealing to learn about is that there’s so much celebration of success cases and there’s a lot of things we can learn from companies that actually don’t survive. So, would love to just hear your summary of, in some ways, the book and the argument, and why actually Foster’s was unable to survive in China.

Mona: Sure. First of all, Foster’s is the largest beverage company in Australia. The title came about as the first joint venture of Foster’s was set up in Shanghai. There are a couple of very interesting coincident key points. The first joint venture started in Shanghai in 1993, which is Shanghaied because consequently they set up the Guangzhou one and then they set up the Tianjin one, so they had three joint ventures altogether. Enormous number of investments actually went into the Chinese market. On their annual review is $256 million. Obviously, there’s a different figure that’s not going on the book. Nonetheless, whichever the number we are looking at, we’re talking about hundreds and hundreds of millions.

Chris: And back in 1993, that was a ton of money.

Mona: A lot, a lot of money. And, of course, till the last day Foster’s withdrew from China did not make even $1 of profit.

Chris: Wow.

Mona: So, a lot of money went down. What went wrong? Foster’s attitude initially was we got this great product which is Foster’s beer. We make the best beer in the world. Fantastic attitude. So, if we go to China, we make it, people will all want to drink it. So many things they did not think about. First of all, is there a beer-drinking culture? The same beer drinking culture is the one we have in Australia? No. Miles apart.

Two, how much are you selling your beer for? Their joint venture in Tianjin, for example, was at a level where it appeared to be very successful because they were selling truckloads, literally truckloads because the opening in the morning, they would have trucks lining up to pick up beer. However, the more they sold, the more they lost because they could not get the price. In 1993, ‘94, ‘96, in the early ‘90s, Chinese did not have much disposable income as they did today. Therefore, they could not afford the price mark that Foster’s set up to sell. And the cost of production was high because we have all these Australian standards: Barley had to malt, everything was imported, and etc. Foster’s just did not consider what would suit the local market.

There are just so many examples of these. One very quick one in China, Chinese would buy their beer, could be any temperature, depending on the shops. So, little local shops would have no fridge. Also, culturally, they believe that you don’t drink beer cold because it’s bad for your health. In winter especially, they turn all the fridge off. So, you buy room temperature beer where Foster’s had the culture of saying beer has to be drunk cold.

And, of course, when beer was also stored outside of the fridge, outside the little corner shop under the sun, gets sunstroke. And, of course, the taste changes, but that’s only to the standards of the brewers in Australia or coming from Australia. So, the Australian brewers went to China, did all this wonderful product and quality control, the whole lot, obviously costly. And Chinese consumers drink the product and they say, “No, this doesn’t taste right. No sunstroke, no warmth. It doesn’t taste like normal beer.”

Chris: That’s interesting. I mean, I’m curious, you mentioned prices, so what was the price differential between the local beer and what Foster’s was wanting to charge?

Mona: At the time, Foster’s beer was about 10 times more than a local beer.

Chris: Wow, that’s a huge difference.

Mona: Especially in a country where there wasn’t a lot of disposable income. You couldn’t expect people to… They probably would try it once. There were just so many cultural stories actually. There’s another very good one on how you translate. Initially, they had someone from Hong Kong who speaks Cantonese to translate. So, the translation resembles the sound disaster has arrived.

Chris: What is that in Chinese Mandarin, 普通话 pǔtōnghuà?

Mona: Now they have translated into Fùshìdá (富士达). Initially was Huòshìdá (霍士达), disasters. So, you have brewers sitting in a five-star hotel and listening to some Chinese looking at this great expensive brand new Foster’s beer going Huoshida. Who’s going to drink one of those?

Chris: There’s a famous example of a similar translation mistake when the Chevrolet brand was entering Mexico. They named it Nova which means it doesn’t go.

Mona: The other very similar story was Peugeot. When Peugeot first went into China, Peugeot in Mandarin is Biāozhì (标志), which says beautiful standard quality, lovely word. But when it’s pronounced in Cantonese, it’s the same pronunciation as prostitute. It was actually funny when I was interviewed by one of the journalists. He said, “Buy one of those and go home and say to wife, “Look darling, I bought you a prostitute, but it’s okay, it’s a French one, so it’s acceptable.”

Chris: Very funny, I hadn’t thought a lot about that before. China with different regional languages, and it’s not just Cantonese and Mandarin, but a lot of different local dialects, that really makes naming a challenge.

Mona: That’s right. And after that, we’re talking about the pronunciation, but picking the characters is another one. Foster’s then moved from Huoshida, so no more disasters. They changed it into Fushida, except the two characters they picked. Fù (富) is a good character. Shì (士) is just character, which it’s okay, except the two characters they picked is the same ones as Fuji Mountain, which then causes a confusion about an Australian beer with Fuji Mountain Reference, and no one could quite understand what it’s all about.

Chris: Has Foster’s reentered China, do you know?

Mona: Foster’s did, but not with this beer. At the time when Foster’s did the beer, it only had beer and later on Foster’s bought a whole range of wine vineyards in Australia, and they added all the ready to drink drinks as well. After its official announcement of withdrawal from China, they then went back into China with wine Penfold.

Chris: Oh Penfolds. Yeah, that is really a high-class wine in China.

Mona: Especially the Bin 888.

Chris: Oh, of course, yeah.

Mona: I think they later on did also Foster’s beer simply through exporting, but it’s never actually taken off in large quantities. And today, if you go to China, you won’t find Foster’s beer. And you ask anyone about Foster’s beer, no one would actually know.

Chris: I like Chinese beer very much. I typically, in the U.S., will drink more like a hoppy type of beer, but the Chinese lager beer are very crisp and refreshing. I don’t like lager beer in the U.S. very much. And I had spent some time in Lhasa, Tibet, and there is a lots of beer which was really, really good. They say it’s because of the mountain stream water.

And they also told me, because Chinese beer uses rice as the grain as opposed to barley, this made it very, very crisp and refreshing. And they told me that actually they do have limited distribution in America, but actually what they do in America, because Americans like barley, is actually they formulate a special American version of Lhasa beer actually in Tibet using barley, and then ship it over. So, you mentioned barley. Did they put any thought into changing their recipe or they were just very stuck on barley?

Mona: Well, in fact, when they first arrived there, that was one of their challenges. They didn’t know their beer could be brewed with rice. And in Shanghai, they indeed found the local brand, Guāngmíng (光明) brand was the local brand that was brewed with rice. Initially, they were going to change from rice to malt. And, of course, that means the cost went up, so you then can’t sell a local beer at a local price, which meant the brewers in fact had to actually learn how to brew with rice. The comment was, once you’ve learned it, it’s actually the same thing because the idea is obviously the starch and the sugar they’re using. So, it’s a matter of get your mind to change around it. That’s all. Way before that, it was like, oh, I heard of it, how could you do it?

The other thing, because you were talking about the taste thing, that’s another cultural difference in the sense that Australians will not drink a beer if it doesn’t have enough strength. The hoppy taste, the alcohol level. Actually, Victoria Bitter was the biggest brand here in Victoria. I think they were at 5.4% alcohol initially, and they dropped it to 4.8 at one point and consumers complained. They could taste the difference. Where in China, especially today, I don’t think I’ve actually seen any beer that’s brewed with more than 2%, 3% of alcohol.

Chris: Maybe we could talk a little bit about your other book, your second book because this Foster’s case provides some really interesting discussion of specific characteristics where a business failed. But your second book, which is called Doing Business Successfully in China, is more about sort of general cultural differences between China and the West. And can you say a little bit about some of those cultural differences that creates some tension or problems for the people for these different countries to do business together?

Mona: I focused on the general cultural differences as one section. And I then specifically look at the cultural differences, how that influences decision makings in market entry, in investments. I then specifically look at cross-cultural management, how to actually manage a team of Australians, local Chinese, and overseas Chinese. And they were actually the three things I categorized the employees, which I guess, at least before my research, no one was actually doing that, especially between local Chinese and overseas Chinese, people just think, oh, you’re all Chinese. That’s not true.

For example, one of the managers is Chinese from Canada, he’s actually still living in China in Shanghai now with kids and wife from China. And when he first went there, of course, he didn’t speak a lot of Chinese, but more importantly, because he grew up in Canada, he was a Canadian. His entire behavior and conduct was all Canadian. And he thought he’s Chinese, he looked Chinese, people looked at him, people expected him to behave like Chinese, but he couldn’t.

There were also a whole bunch of other ones. The ones from Hong Kong which had cultural issues because, before ’97, as we know Hong Kong, people thought that they were above the mainland Chinese, where the mainland Chinese did not entertain that concept. So, there’s a sort of constant conflict. One of the Hong Kong Chinese who worked for Foster’s in Hong Kong literally would not spend time in Shanghai. He would fly in in the morning and fly back in the evening. And so, the local Chinese, of course, did not sort of really accept him. And the other section I look at is cross-cultural marketing, which is to look at brand names, similar values and what consumers look at from the Chinese perspective as value and what Australians saw in the product as value.

Chris: Yeah, so what are some of those differences that maybe Chinese consumers would focus on versus Australian consumers?

Mona: If we talk about marketing of products, for example, we mentioned the cost of producing a product. The brewers believed that because they had their system of producing their beer and that they followed the same system. They can’t cut corners, everything is all very important. One of the problems they did encounter in Shanghai, the early days, is your electricity and heat maybe turned off at some point. For the Australian brewers, if you got a brewer on, the temperature has to be kept at a certain level. If the temperature drops, you pour the entire brew down the drain. Therefore, in order to make sure that your heat and your electricity doesn’t get turned off, you must have the local people who are in charge of the heat or electricity for dinner regularly. And, of course, the first thing the Australian team said was, “There is no way. That’s called bribery. We will not do that.”

And, of course, they found the electricity’s being turned off at any hour. The steam turned off for hours. They were pouring down the drain brew after brew after brew, until they came back, and realized perhaps we should resume the old tradition. So, that was one of the very good examples. There was another one. They were trying to get some bottles from another city. And, of course, the official line from the railway station, the railway master was “we have no space, we cannot ship these bottles for you.” Of course, the Australian executive team initially said that we don’t entertain, we don’t take anyone for dinner. So, there were no bottles, until the point where the local team told the Australian team that we really must do it. They had dinner. Next day, the boats were on the train.

Chris: Your background is so interesting, I think, I mean not only have you written these books and you were a professor at Deakin University for a while, you also have BlueMount Capital, where you actively work to advise companies actually entering China and doing business in China. Can you share a little bit about that experience, how you took these insights that you had from your research, from your experience, and now help companies as they do business in China?

Mona: To answer that question, I’ll probably introduce a little bit about myself and my history and background. I always called myself a reformed academic while I was in university. The reason being I came from business. My first degree was in international trade. I did that at Swinburne University. Then, when I first came to Australia in 1989, people used to ask me, “What did you do at university?” I used to say international trade, and people used to say, “What’s that?” Time has changed now, of course. But then I was consulted often by people, mostly Australian firms who wanted to do business with China, with Chinese. Very often they would come to me to say, “Look, we started to do whatever.” Say, we’ve got a product and we want to export this to China. And we started to meet Chinese. I used to give people advice at the very beginning on how you should conduct your relationship side and negotiation, etc.

Very often people would go away and do things their own way, and I often wouldn’t hear from them for a while. Then I would hear from these people just totally out of the blue. Occasionally, it would be 10 o’clock at night, and there was once, I think it was 12:30 at night. So, that person must have been rather desperate, I suppose. And usually, it would be, “Oh Mona, the Chinese don’t talk to us anymore.” There would always be the opening line. So, I’d go back to let them tell me the stories of what happened, what they did. What usually happened was, in their communication, those days also Chinese spoke less English than they were today as well. So, in their communication, something went wrong, and clearly things would go, one little misunderstanding turned into something else, and something else, and something else. So, months down the track, it will be the angry Chinese on the other side.

Typically, the cultural difference is to preserve harmony and not to have a conflict. It’s better not to talk to the other side, because if you do, you can have a fight. So, this is the time when they just don’t talk to the Australians anymore. And then the Australians call me and then I’ll get to speak to the Chinese and then I’ll hear on the other side all these angry stories, “He said these, she said that, and she did these, and he did that.” You could just hear, oh, I guess you misunderstood that. It’s either through the misinterpretation of behavior or misunderstanding of the language or misunderstanding of how language was translated and the whole range of things. So, at this point, I then sort of thought, I better look for some literature to give to people to read. And my argument was you need to do some more homework before you jump into the deeper end.

At that point, I could not find much research on doing business with China or cultural differences. I then went to do a master’s degree, and then few of the colleagues after I nearly finished the degree, and few of the lecturers then said, “Oh Mona, I think this is a really good PhD topic in this. Why didn’t you do one?“ I just thought, didn’t know what a PhD was at the time, I just thought, oh yeah, it must be a good thing to do, so I did. And only when I got into it, I realized what I sort of committed myself to, but no regrets. I was also doing some work with Foster’s at the time, so look at how Foster’s were just basically wasting money at the time. I sort of said, “Look, even if I have a small portion of these, we could do something differently and turn things around. At one point, their losses in China were $44 million a year. And one executive that they employed managed to achieve a very, very huge achievement in his terms, was to reduce the loss from $44 to $24 million.

I thought, look, this is the best case study that I could actually use to base my PhD on plans, all the contacts I already have. So, then I had the support from the company as well. It was really a wonderful journey because it was always quite an enjoyable journey as well to talk to people and learn about things. From there, I continued on with the university until just before COVID. Somehow I obviously had a vision to time it quite rightly that I decided to… Because I was actually doing a lot of research teaching, at the same time I was doing some consulting work which was getting a little bit too much. At one point, I would finish teaching, hop on the plane, and in a couple of days, come straight back. And I was getting just a little bit over the top. So, I decided, look, I’ll just do the consulting work. Since joining BlueMount, I managed to actually set up a BlueMount office in Beijing in 2019, which again was great timing. As soon as we set it up, we have COVID.

Chris: But still, I think, actually, someone like yourself is probably all the more valuable now because, obviously with COVID, there’s been some interruption in trade, but also there’s been, I think, even a more consequential interruption in people going back and forth. So, I think that some of these misunderstandings that you’re talking about are much easier to happen cross culturally, and so having someone like you who really understands both cultures is probably more valuable than ever.

Mona: Very much so. Previously in my working in this cross-cultural communication negotiation space, I previously often found myself in, say, a conference negotiation session. It will be like Mr. Jones said such and such, but what Mr. Jones means such and such. That Mr. Jung said in these words, but what Mr. Jung really meant is such. Oh, that’s what Mr. Jung wants to do and that’s what Mr. Wong wants to do. Right. Mr. Jones actually wants these, not what is said on paper in words, which we don’t understand what he actually wants.

Chris: In your work at BlueMount, are there any clients or cases that you have that really encapsulate or illustrate some of the current challenges that companies are having in China?

Mona: Probably the best example of my current client, this is a wagyu export business, and this has been the most challenging thing for us for the last nearly three years since the last time we were in China was January, 2020.

Chris: This is cows raised in Australia, their meat being exported to China, is that right?

Mona: Correct. The Japanese species of cattle. They’re different from our ordinary sort of beef and steak. They have much higher fat content in their meat, and so the marble score is what the Japanese raved about. I think the U.S. was the first country that brought these cattle out of Japan, and then Australians very quickly got onto that and realized that this is a very much nicer product. Japan now won’t allow those live cattle to be exported anymore. Since 1997, they’re not allowed to export them because they’re a national treasure. And, of course, the last couple of years, I think one of the biggest challenges is that we couldn’t go to China. A lot of the communication can actually see people’s reaction, people’s response to things that’s being said. A lot of those things can’t happen. It’s rather challenging when you only rely on WeChat and some basically, if you haven’t got enough data, you don’t use video either. Even with video, it’s not quite the same thing as face-to-face.

Chris: I’m curious about the wagyu, it’s an interesting counterpoint to what you were saying about Foster’s in the expense because presumably those steaks are a lot more expensive than the Chinese grown beef, but obviously, they’re able to achieve this status, prestige based on the type they are. Can you say a little bit about how the price aspect is managed? And actually, sometimes I think having a high price is even better than having a low price because it sort of really signals the status element.

Mona: Very much so. That’s another cultural element for the Chinese. It’s always this showing off element in Chinese culture. Whether you could afford it or not, that’s a separate question, of course. If you can’t afford it, you still can’t show it to other people that you can’t afford it. So, you have to make sure everyone can see that you can afford it. Although, the changes in the Chinese economy have brought a lot of people with a lot of income, so they can actually afford wagyu. This company, it’s the reverse. Foster’s was lots of money being invested into China by the Australians, where this company is a lot of money being invested by Chinese investors into Australia. And cattle are grown here, bred here. They’ve been fed on grain and then they’ve been slaughtered, and then packaged specifically for China. And the company also exports to other parts of the markets as well.

China was initially, probably the major and the biggest market, still the biggest market because of the risks and the political relationship between Australia and China, especially in the last few years with the previous prime minister. There’s always a desire to sort of reduce that reliance on the Chinese market. Nonetheless, never enough we can produce here. Plus, wagyu is a very expensive product. You don’t really need to eat like a big chunk of 500 grams of meat. The Japanese sort of slice them, they’re really, really thin. They usually cook them on a barbecue or something but it’s quite thin. And the Koreans do very similar things, and Chinese do very similar things too.

Chris: Another topic I wanted to discuss with you is Huawei. I know you’ve done a lot of writing on Huawei as well. And this is, at least from the U.S. perspective, a company that is frequently in geopolitical crosshairs, and obviously hugely innovative national champion in some way in China. I’ve actually been to a few of the Huawei locations in Shenzhen, and also a research lab of theirs, very huge, gigantic building in Shanghai. And always amazed that 70% of their employees I think have PhDs or engineering background, and this huge number of patents that they have. So, two questions I want to ask. One is how you see this tension, how Huawei can position itself vis-à-vis the tension. Then also in relation to that, so Ren Zhengfei, I think about a week or two ago, wrote a letter about how the next decade is going to be a really tough, painful time for Huawei. Just any reflections you have on that as well.

Mona: Yes, we did do a lot of work on Huawei and wrote quite a few papers and chapters on Huawei. Huawei is a very interesting successful story obviously for China. I think, no doubt, it started with copying devices, equipment. It’s a very cheap way of offering consumers a cheaper alternative. But I think Huawei has grown from its initial start, I think it’s 1992 from memory when it started. As you mentioned the huge R&D centers, they have a very large R&D center in Europe as well. They invest a lot into R&D. It’s a success story of a Chinese company by producing the lower end of the product. By the time they have large sales and more revenue, then they can afford to do the R&D.

I think the story with Huawei is unfortunately a political one. There’s always the talk about Ren Zhengfei’s connection with the army. And, of course, in Australia, the Australian government always use that as the army connection. I think it’s very naive of any western government or countries or companies to think that Chinese companies don’t have connections with Chinese government. Right now, Chinese government still owns 50% of their enterprises roughly. Where previously, the beginning of economic reform, Chinese government used to own 85% of the enterprises. So, it makes sense that if the government owns all the enterprises, then, of course, they’re interested in how to run these businesses. They need to make profit; they need to make sure so these companies can continue. The talks about Ren Zhengfei’s connection with the army was that he was in the army and then he left the army, which is again common.

There’s no way I guess we can ever confirm whether he still does or doesn’t. But nonetheless, he’s now just a citizen. But that’s always been the talk about you cannot trust Huawei. If Huawei does all the communication equipment, and there’s the connection with the army, I guess if we look at the other side of the communication in the west, what does the FBI do, CIA do? Every country has its intelligence. Where I think it appears to become a problem is that the CIA can collect intelligence, the CIA can conduct whatever it conducts. ACO can do whatever it does. If the Chinese government does it, it’s not acceptable.

Chris: It always does seem very targeted and one-sided to me as well. I mean, I think it’s very reasonable to say okay, for national security reasons, we’re not going to have non-domestic partners in our telecommunications infrastructure, and I think China obviously does that. But of all this saying, oh, this person is corrupted by the government, these are things like the Snowden and other leaks showed, oh excuse me, all countries are doing this, and so I think we just should be honest about things instead of always pointing fingers.

Mona: Precisely. So, to answer your second question about his talk or paper really was more of an internal memory that was being leaked. Looking at what’s been happening with Huawei in the last couple of years, as we saw these bans between the U.S. and China, and all the chip banning, the selling of the chips to Huawei, Huawei’s revenue has been going down year by year and quarter by quarter. There are some figures I think are quite significant. We’re not talking about going down by 2% or 4%. We’re talking about going down by 29%, 19%. That’s huge amount. Which actually doesn’t surprise me to read what Ren Zhengfei said about it. So, if your company’s revenue is going down 30% every quarter, you would be very quickly on the survival mode, which is what he said. I only read the English version. I think is where there is a difference. If I could get to read the Chinese version of the paper, I possibly would have a different interpretation. But I did read in one of the comments from one of the Chinese journalists or analysts actually did talk about the tone in what he wrote. I think the word this analyst used was panic. I suppose if I were the CEO or director of a company, and my company’s going down 20%, 30% every quarter, I think I would probably panic earlier.

Chris: At one point, maybe before the trade war, like $120 or $150 billion in annual sales, and so they are probably still selling a lot. But yeah, the definitely the year-on-year rate must be very, very concerning.

Mona: And plus, the trade war also meant that there are certain parts, especially the chips the U.S. is not selling, or not allowing even related competition to Huawei, which shortly impacts on the capacity of producing certain products or the quantities.

Chris: Yeah, it’ll be interesting to see how that sort of continues to play out. One last specific question in regards to sort of your research and writing I wanted to ask because it connects to some of the work that I’ve been doing recently is on the lasting importance of Mao and Maoism. And this is how I came across some of your work actually initially in, I think it was your book doing business successfully in China, that you talk about the lasting importance of Maoism both in various control aspects, but also the lasting effect of the cultural evolution. Can you say a little bit about that work that you did and which your findings and ideas were?

Mona: Maoism is a very important cultural element, I put it in modern Chinese history. When we say modern, it’s already been 70 years. The Cultural Revolution, the Chinese government recognized it as a mistake. I think in the current textbooks or education in schools, it’s not very much taught in-depth in the attempt of perhaps pretending it didn’t happen, but it did happen. And what it changed is the traditional Chinese culture. Confucianism, the levels of structure in the society, which is on top of whom, the relationship between the father and the son, the state and the individual and all of those things has changed very much.

The other very important thing about Maoism is how Mao actually changed the position of women in China. The very traditional Chinese culture, the father is the head of the family. If the father passed away, then the older son became the head of the family, not the mother, even if the son as a tiny little kid. But Mao actually made all women leave the house to go out and get a job. Initially, women didn’t like that. Working and jobs and profession, etc. meant the women then had income. Once they have an income, they have independence. Where previously, they did not have that. One of the very famous slogans Mao used at the time was women hold half of the sky.

Nowadays, we see very big differences in Chinese organizations. For instance, you see a lot of females in very senior positions, sometimes more so than we see them in Australia. And people don’t really blink in China to have a female or a male in those senior positions or to have females above males. On that particular topic, when I first came to Australia, I felt the culture here was backward than the Chinese way, that Chinese sort of progressed.

The Cultural Revolution is another very important one. We mentioned what Cultural Revolution did. It broke a lot of the traditional links of the culture, which is a shame because there was a lot of very valuable artifacts, all been destroyed, which is a total shame of that part of history, which is why I suppose the government try to pretend it didn’t happen. One other very terrible thing that was caused by that Cultural Revolution is the change in the relationship between people. The very fundamentals of Chinese culture is relationship-based and lots of trust was broken during that period. Through those movements of denouncing rights against all sorts of movements, husbands and wives were denouncing each other and telling the party, what they said in the bedroom and things like that, which previously never heard of. The relationship has sort of been changed between people.

I think today people are less trusting toward each other, although the basis of the society is still relationship-based. When you have a relationship-based system but you don’t trust people as much when you really need to, sometimes causes this conflict. So, you get to hear a lot of stories now coming out of China, how people cheat each other, and fraud, and that sort of thing. We get it here too, but you tend to get some extraordinary stories coming out of China.

Chris: The women holding up half the sky quote is so interesting. I mean, that gets used around the world. Actually, when introducing Kamala Harris, the vice president, Biden actually used that quote, and I don’t think he realized he was quoting Mao.

On the interpersonal trust point too, I’ve seen some recent survey-based analysis from some economists and political scientists that actually show the lower levels of trust of people who actually went through the Cultural Revolution, and in places where there was more extreme Cultural Revolution activity. The research that I’ve been doing in the book I have coming out actually shows some findings that actually business people that also experienced it are more likely to be caught in corruption scandals and be on these lists of shameless debtors. So, I think there’s definitely something to what you’re saying.

Mona: When is your new book coming out?

Chris: It’s coming out November actually.

Mona: I’m looking forward to reading it.

Chris: Definitely. I’ll make sure to send you a copy.

Mona: Thank you.

Chris: Last question, we’re just about out of time. So, let’s say a business from Australia or the U.S., or the U.K., Western countries are interested in entering and doing business in China now, in today’s current environment, assuming maybe COVID restrictions are going to be softening hopefully soon. What’s your two or three pieces of advice for them?

Mona: My key message is the cultural differences, realize that there are substantial cultural differences between the two countries. The way it is coming back to the fundamentals about cultural differences is that those cultures determine the way people behave in that society and make that society work perfectly well. When you enter into that society with a different set of cultures and different ways of doing things, I think the key message should be don’t try to change the local culture. One is you’re not gonna succeed. You’re going to fail because it’s something that works in the local community. You can’t change it. Two is that whatever the attempt you make is really just going to make the attempt of trying to succeed less effective because you are wasting all your energy on trying to change things that you can’t. So, that probably would be my number one.

And number two, I’d say look, you got to look at the cultural differences and use as the guidelines of your strategic plan. It’s not at the other way around. Because one of the biggest mistakes that Foster’s made was they took these strategic plan in Southbank, and they take it to China, and they say, “Let’s just copy.” And in Foster’s case, because that’s what they did, they constantly found the strategies in China didn’t work. Of course, it didn’t because it wasn’t designed for it. It’s a bit like building a house. We have flat roofs and thatched roofs, and if you use the wrong roof in the wrong time zone, it won’t work, and then you can end up fixing it all the time.

So, once you have a strategy that’s based on cultural differences, I think the third message is to pay attention to your communication and negotiation, and that is going to be a constant thing. The Western business practice can see this negotiation as we enter into a negotiation, doesn’t matter how hard we bargain or whatever we do, we reach something at the end, and that’s it. We write it down and it’s finished. For Chinese, negotiations are an ongoing thing. Whatever we write down or we agree to, we can always come back and revisit it. And my advice to my client, always use that to your advantage. Why? Because circumstances change, people change, situations change, conditions change, everything changes. Why do you want to tie yourself down by a piece of paper where you’ve got no room to move?

Chris: Thank you very much. Really appreciate you spending the time with us today on China Corner Office, Mona.

Mona: Thank you, Chris.