Luó Yǔfēi 罗雨飞 was a product manager for a Chinese educational technology company until he was laid off in July this year, the delayed results of the government’s decision last year to stamp out the private tutoring industry.

Luo, 28, decided to stay jobless to recharge from workplace burnout. With plenty of time on his hands, he began spending his evenings prowling through Beijing in search of valuable goods abandoned on the sidewalks.

“The streets are a home goods buffet if you know where and when to look,” he told The China Project. On a recent trip last month, Luo started scouting in his neighborhood, Beiluoguxiang, a mostly residential area of traditional courtyard housing. Finding no luck there, Luo cycled his way north to Wudaoying Hutong, a renovated alleyway that has become a hip shopping destination for young Beijingers.

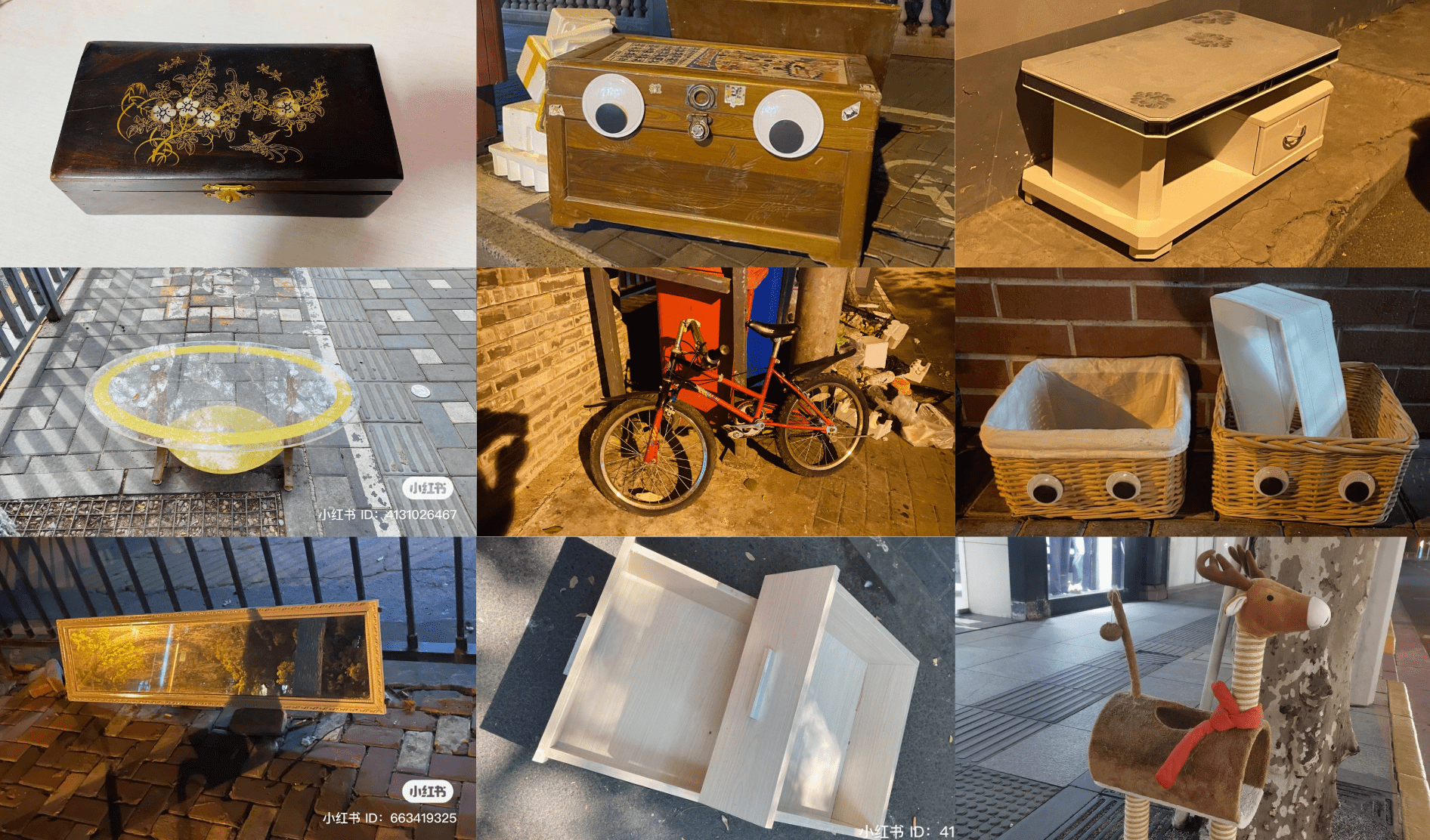

Amid cafés, boutique shops, and residential buildings, Luo spotted an acorn wood jewelry box with velvet lining and a mirror inside. The item was obviously used and visibly damaged — it had a crack, Luo said, which made him believe that it had been tossed away by a vintage store nearby. His next find was a white storage shelf that was “perfect for houseplants and books.”

But the biggest gain of the night was a pair of antique Chinese rosewood armchairs. Sitting in front of a public restroom, the furniture was “too good to be discarded,” Luo thought to himself. Unsure if they were available for the picking, he waited around for their owner to appear. After half an hour, Luo made the call that the chairs were freebies up for grabs. He snapped a few photos and shared them on social media with a caption saying, “They are heavy but in relatively good condition.” Hours later, one of his followers on Xiaohongshu, China’s Instagram-like lifestyle platform, showed up and took the furniture home.

From New York to Shanghai and Beijing

In Beijing, Luo is one of the early adopters of “stooping,” a practice that also goes by the names “trash stalking” and “curb mining.” It has long been a tradition in New York City, where stumbling upon sidewalk castaways is a common experience and taking them home is socially acceptable. But it was not until 2019 that the behavior came to be known as “stooping,” and was taken to a whole new level thanks to a slew of Instagram accounts such as CurbAlertNYC and Stooping in Queens, which routinely share photos of notable street finds that are ready to be stooped.

The anonymous Brooklyn couple behind StoopingNYC, the most popular stoop-spotting account among the batch, say that they started the account in August 2019 after marveling at the amazing sidewalk finds they came across while strolling around the city. Within a few months, the account doubled its follower count and the number of submissions they received shot up as the pandemic dragged on, as urbanites fled the city, leaving an abundance of valuable garbage behind. After more than 15,000 posts, Stooping NYC now has more than 407,000 followers on Instagram.

Residents of cities outside the U.S., such as Amsterdam and Toronto, have created similar Instagram pages. And in the summer of 2022, the phenomenon made its way to China.

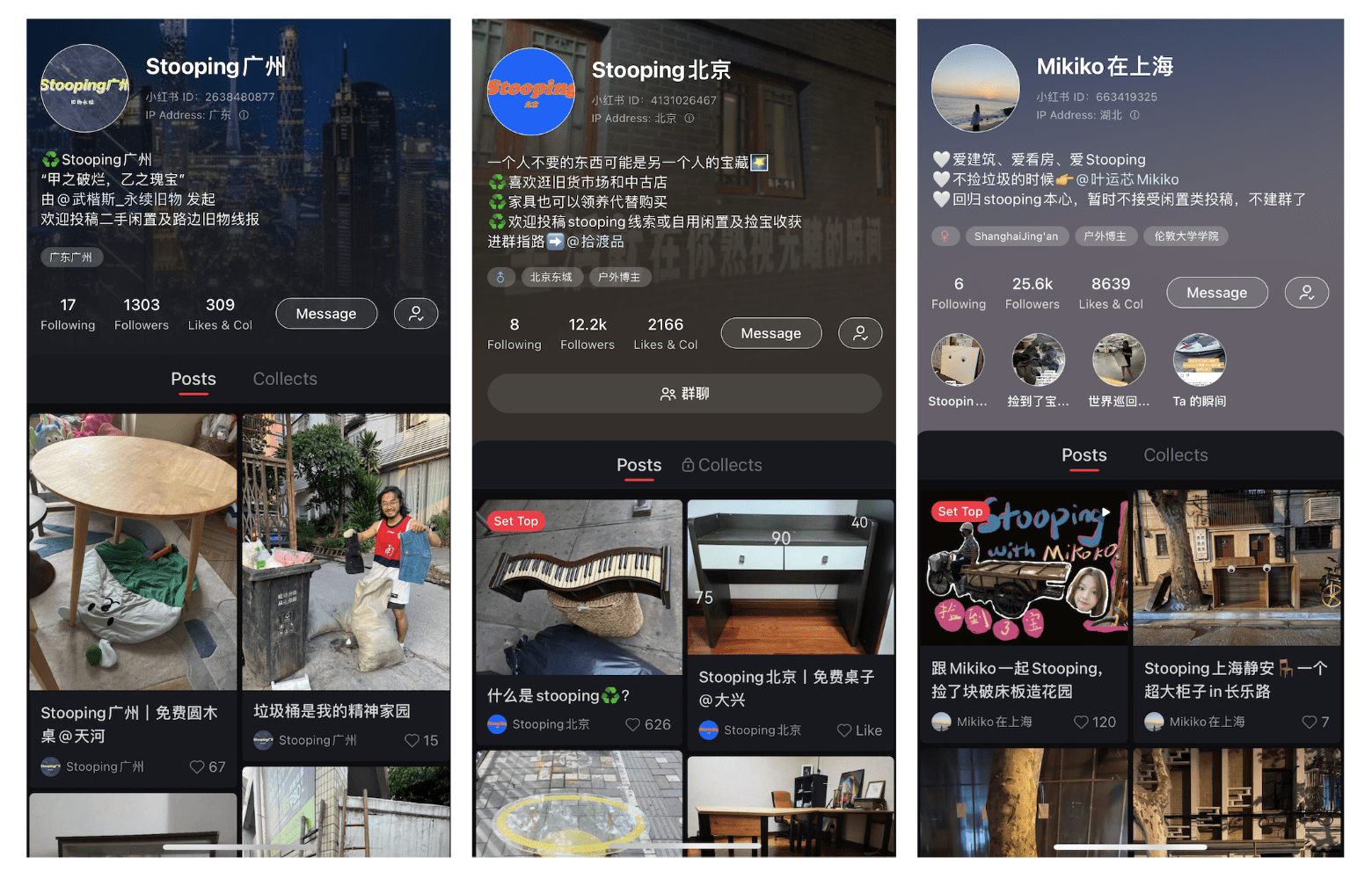

Luo was introduced to stooping on a sleepless night in late August. When scrolling through Xiaohongshu, he saw a post by Mikiko in Shanghai (Mikiko在上海), the first Chinese social media account dedicated to stooping. Launched in June by a twentysomething real estate agent in Shanghai, the account boasts nearly 26,000 followers.

“It instantly piqued my interest,” Luo said, adding that he had frequently spotted valuable discards in his neighborhood, but he didn’t know there was a term for it. Calling himself a “thrifting aficionado” and a “skilled scavenger,” Luo continued, “I didn’t have an allowance when I was a teenager and I had to look through garbage pails, sifting for bottles and other valuable items, to earn money.”

Hoping to bring the culture to his city, Luo created StoopingBeijing, where he chronicles his finds and maps curbside castoffs via citywide community submissions. The account now has more than 12,000 followers, a figure that far exceeded Luo’s expectations.

Most of his discoveries, Luo said, were left behind by people like him, who work in Beijing but do not have permanent residency there. Known as běipiāo 北漂, or Beijing drifters, these renters tend to move around a lot due to changes in their career or housing situation. “I’ve definitely faced the anxiety of not knowing what to do with my belongings when I moved out of my old apartments. Many people would just leave everything they no longer wanted in the house for landlords to dispose of.”

From Long Beach to Guangzhou

In Wǔ Kǎisī’s 武楷斯 three-story home in suburban Guangzhou, almost everything — including the mattress, the couch, the curtains, and the power strips — was schlepped from the curb. A law graduate from a prestigious university in southeastern China, Wu was first exposed to stooping when he embarked on a three-month backpacking adventure across the U.S. in 2015. In Long Beach, California, Wu spotted a functional fridge labeled “for free” on the sidewalk — and it “basically changed my life,” he told The China Project.

“I was shocked. It’s unfathomable that someone in China would put out something this nice on the streets for people to snatch,” Wu said. “The culture here is to squeeze money out of everything. For most people, if they are getting rid of something that they still see value in, they would hire professional garbage collectors to pick it up for a meager return.”

The cultural shock experienced by Wu in the U.S. turned out to be fate-altering. After returning to Guangzhou, he decided to lead a minimalist lifestyle, putting a ban on himself from buying anything other than underwear. After graduation, Wu turned his passion into a career. He now owns two thrift shops, one in Foshan and one in Guangzhou.

Wu, who has been featured in the local media as a “radical” advocate of anti-consumerism, is also the curator of StoopingGuangzhou, a Xiaohongshu account he started in early September after seeing stooping take off in Shanghai and Beijing. “I tried to see if there was one for Guangzhou, and there wasn’t. I felt I was best positioned to start this account because I know my way around garbage and am well versed in the language of social media,” he said.

Stoopers vs. trash collectors

In Beijing, veteran trash stalker Luo Yufei said that his “biggest rivals” in getting hold of good discards are the city’s street cleaners, who are “insanely efficient in removing bulk items from the public eye.” To avoid competition, Wu usually goes on curb-mining excursions between 12 a.m. and 4 a.m., before public janitors clock in for work in the early morning.

Prime foraging destinations in Guangzhou include historic neighborhoods like Yuexiu District, where Wu Kaisi said “it’s easy to spot antique furniture thrown out for small minor dings or otherwise repairable issues.” Wu also has had success in Tianhe Central Business District, the city’s economic center, where “office workers would frequently dump high-value objects in garbage bins.”

For Luo in Beijing, the end of the day is always a good time to scavenge abandoned treasure, as young professionals head home from work and find time to declutter. In terms of location, Luo prefers trendy shopping areas, where “lots of retail shops have gone out of business during the pandemic,” yielding a plethora of freebies on the curb. In hutongs, or narrow alleys lined by courtyards in downtown Beijing, one has to carefully discern actual undesired stuff from outdoor furniture and other property of local residents.

“Many elderly residents of hutongs have their designated spots to hang out during the day. They usually leave their chairs outside when they go home. If I see a group of, say, four chairs put next to each other, I know they are unavailable for the taking,” Luo said. “Otherwise, things placed near garbage bins or public restrooms are usually free to score.”

Spending is out, frugality is in

“My followers are a mix of environment-conscious consumers, young people who want to be part of a new trend, and those who can’t afford to shop new,” said Wu. “The common denominator is that they are looking for ways to save money.”

In the past year, China has faced harsh and protracted coronavirus lockdowns, high youth unemployment, and a deepening property slump. Consumer sentiment has tanked, forcing people to rethink their spending and saving strategies. Young professionals feeling economically squeezed are choosing to eat fewer meals in restaurants, and skipping beauty salon visits, or even haircuts. Meanwhile, on lifestyle apps and video-sharing sites, influencers flaunting wealth are losing audiences for seeming out of touch with reality. Instead, those who share money-saving tips and tricks are gaining followers.

Victoria Ma, a 25-year-old freelance writer in Shanghai, nabbed a gray, velvety couch from Changning District after seeing its photo on Mikiko在上海’s Xiaohongshu page in August. She has recently moved to Shanghai and has a limited budget for furnishing her apartment, so the appeal of the piece outweighed the perils of bringing an item of unknown origins when COVID-19 was still lingering.

“I wiped it down thoroughly before it entered my living room,” May told The China Project. “Sure, I can get something similar from a furniture shop, but that would cost me probably hundreds, if not thousands, of yuan.”

Despite her stooping success story, Ma still considers herself a “passive recipient.” She said she checks Mikiko在上海 at least three times a day, but she hasn’t gone for walks to actively seek out unwanted stuff.

An ethical market for stooping?

In the eyes of Luo, stooping pages are community efforts. When he’s not out on hunts, he manages eight stooping-themed WeChat groups, a collective of nearly 4,000 members. In theory, these groups were built for participants to share photos with addresses so that fellow stoopers can rush to pick up the finds. But in practice, they function more like Facebook Marketplace, an online flea market where users can buy and sell pre-loved items of all kinds.

“Givers in these groups are largely people who want to sell unneeded items for a fraction of the original price. Some generous ones will give away stuff for free,” Luo said. Some basic rules are established and strictly enforced, such as no trading of living things like pets, but overall, Luo takes a “hands-off approach” to regulate messages, in the hopes that the community will grow organically.

Not everyone agrees with Luo’s principles, though. The most common complaints received by Luo are about freeloaders who make others feel awkward with their unrealistic expectations. “They would write they want things like cameras and electric scooters, which are not cheap. I’ve gotten private messages complaining about them looking entitled or acting like panhandlers,” Luo said. “But I fear I will lose these people if I take a hardline position on this. I value every member of my community given that it’s still very new.”

Wu is a huge advocate of expanding the definition of scooping to include shopping secondhand. The ethical foundation of stooping, he said, is “making good use of every object in your life,” which also underpins bargain hunting. “For sellers, they spend time making listings in order to find a new home for their pre-loved items. For buyers, they spend time looking for good deals,” Luo said. “Both sides are championing the ideas of waste reduction, sustainable living, and diverting items from landfills. In the end, everyone wins.”