Francis Fukuyama on the risky path Xi Jinping chose for China

As China navigates an uncertain post-COVID-zero future after highly unusual nationwide protests, celebrated scholar and author Francis Fukuyama spoke to Audrey Li Jiajia about what we can learn from the events of the past few weeks.

A year ago, it seemed that authoritarian governments were winning. In China, Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 presided over a country that grew its economy by 8.1% in 2021 while keeping COVID infections under control: The country reported just two deaths from the disease in 2021. In March 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin visited Beijing, where he and Xi talked up a “no limits” partnership between their two countries as the West reeled from both the coronavirus pandemic and a variety of political malaises like polarization and far-right populism.

But then Russia invaded Ukraine and is now bogged down in an unpopular conflict, while China went into an almost-permanent lockdown that is partly responsible for a severe economic slowdown and has now ended in a chaotic retreat from COVID zero. Authoritarianism does not look so good anymore.

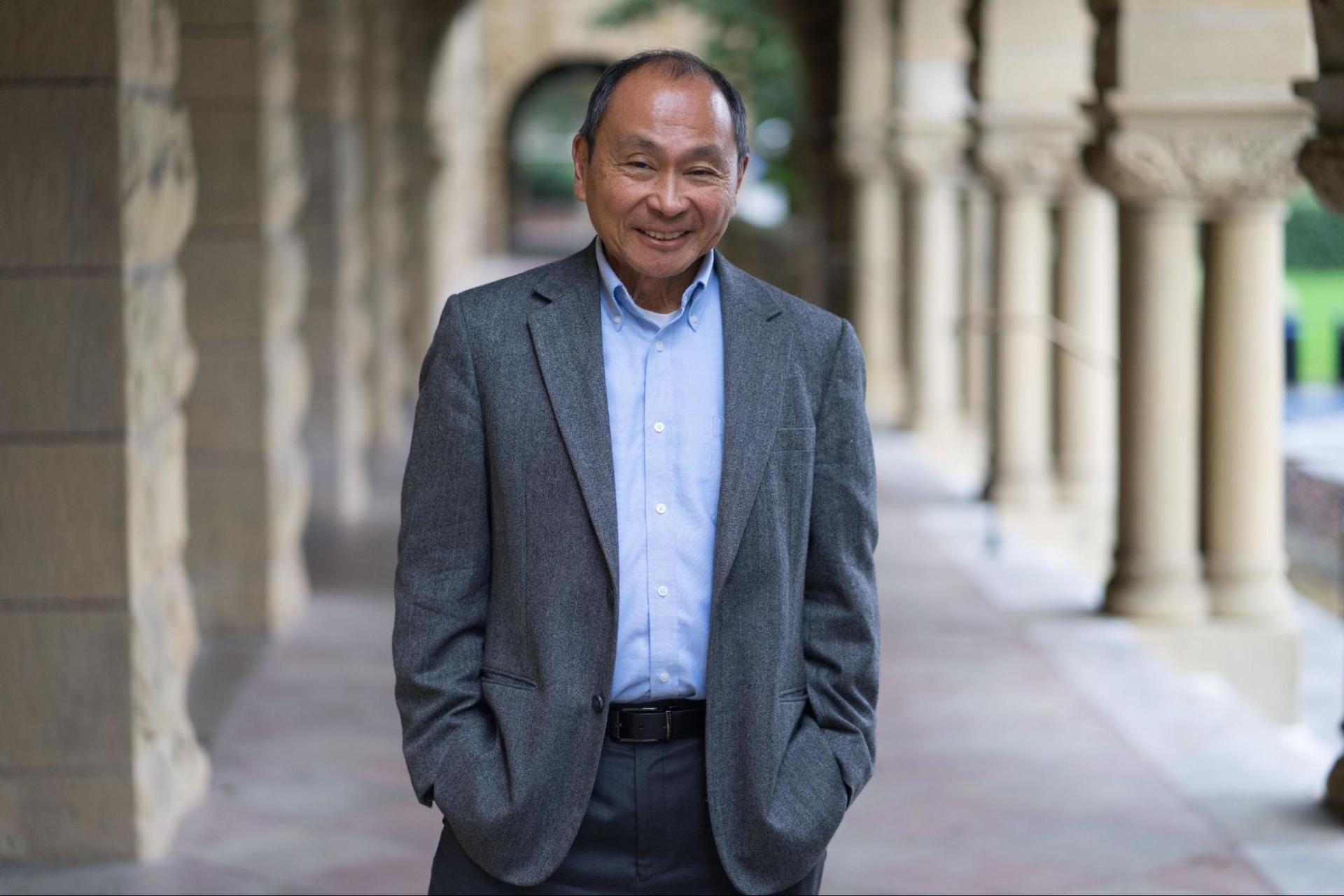

So it seems like the perfect time to talk to the renowned scholar Francis Fukuyama, who gained fame after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the fall of the Berlin Wall, and is best known for his book The End of History and the Last Man. Some of the arguments of the book have subsequently been scrutinized by some who believe he underestimated the energy of authoritarianism and overestimated the strength of liberal democracy. But Fukuyama, in fact, hasn’t stopped fine-tuning his views along the ever-changing steps of history over the past three decades.

Early this year, his new book, Liberalism and Its Discontents, took a serious look at the challenges to liberalism from the right and the left. And in October this year, his article “More Proof That This Really Is the End of History” argues that over the past year, it has become more evident that there are key weaknesses at the core of seemingly strong authoritarian states, notably China and Russia.

Fukuyama took my questions earlier this month on liberal democracy’s discontents, China’s protests, and Xi’s leadership.

—Audrey Jiajia Li

On China’s protests

As we all witnessed recently, protests spread across China, reflecting the rising public anger over the draconian COVID control policies. Some in a crowd in Shanghai even directed their fury at the Communist Party and Xi Jinping by chanting “CCP, step down, Xi Jinping, step down.” None of these would have been expected in China in general, let alone in the Xi era.

Given the fact that most Chinese youths have actually become more and more nationalistic over the past decade, did you see this coming, or did you also find the demonstrations surprising?

I don’t think the protests are at all surprising given the severity of the lockdowns. It seems to me that it has several different consequences. The direct consequence of being forced to stay in your apartment or a house, or not being able to go out, not being able to see your children if you’re separated from them, or not being able to buy food and so forth. The other thing personally that must make a big difference is that it’s very hard to see how lockdowns end, because the rest of the world has pretty much opened up, but in China the number of infections has been going up pretty steadily and the scale of the lockdowns is spread — something like a quarter to a third of the whole population of China still under some kind of lockdowns. So I’m not surprised that people don’t like this.

The other big consequence is China’s economic growth. Because this is obviously taking a huge toll on China’s GDP. Although the regime says that they have 3.9% growth I don’t think any economist really believes that. I think many people in fact think over the last quarter or two China could have experienced negative GDP growth. For example, a lot of migrant workers are having to go back to their homes in rural China because their factories shut down and they don’t want to be in a lockdown in a different city. So I think altogether it’s kind of amazing that this didn’t happen earlier.

Beyond that, there’s a legitimacy problem. The legitimacy of the Communist Party really depends on its performance of the fact that it’s been bringing economic growth and stability to China. But the moment it stops performing then people will start to ask why — why do these people have to have the right to rule and I think that’s why the economic slowdown is extremely significant.

So what do you think is the reason Xi Jinping has been so determined to stick to COVID zero over the past three years? Does it speak of some kind of hubris?

I think there’s a number of things. One big problem that he still has is that the rate of vaccinations is much lower in China than in other countries. China was not willing to import any western vaccines and the domestically made vaccines are much less effective than the western ones. And the rate of the elderly vaccination has been very low. And because they’ve kept COVID out of the country, nobody has any natural immunity. Where I am in California practically everybody including myself has gotten COVID over the last couple of years — the later variants are more mild than the early ones — so I think that we have a lot of natural immunity and that simply doesn’t happen in China. So it’s really very hard to relax the policy.

But I do think as you suggested that his own vanity as a leader is at stake because he has staked his whole reputation on China having a much lower rate of COVID than Western countries. And that’s been true up till now but it’s been at this enormous social cost and economic cost. And I think that he finds it very hard to back away from that, especially since he’s effectively become a leader for life after the 20th Party Congress.

That a strong and successful leader can never be wrong or otherwise seems to undercut his authority and show weaknesses.

That’s right. I think he has built a lot of his reputation around China just being the most successful society in the world. And now it doesn’t look that successful so I think it’s very hard for him to admit that he was wrong about this.

The other thing, if he backs down in the case of protests it also will make him look weak but if he clamps down on the protests and arrests people and continues these lockdowns it’s also going to be bad for him. So I think he’s really stuck in many ways.

Actually, he did back down to some extent. After the protests, as Beijing suppresses dissent, it is at the same time moving to address the grievances. We’ve seen lockdowns lifted and policy shifts expanded over the past week. So in that sense, the demonstrations have worked. But some protesters also chanted for democracy, freedom of press and expression, as well as an end to the authoritarianism that had enabled “zero COVID” in the first place. Do you expect the compromise on the government side signals some more fundamental changes to follow?

I really doubt that there’s going to be a fundamental change in the nature of the regime. China all along has not been as repressive as some other authoritarian countries. And oftentimes when there are protests about land seizures or against treatment of peasants, the government changes policy and tries to accommodate some of the complaints. So I think that they’re going to continue to do this. The problem of course is that they can’t really fully open up without letting the disease spread on a very rapid and massive scale, so they’re limited as far as that’s concerned. But that’s very different from actually winding down some aspects of the nature of the regime, having to do with the one man rule and the dominance of the Communist Party. And that I think is far too important to Xi Jinping and to the other senior leadership for them to really make any compromises on that.

On Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power

Is it accurate to say that in your article “More Proof That This Really Is the End of History,” you concluded that China’s problems in combating COVID are actually rooted in what you call the “personal autocracy,” and that it might have been avoided if the pre-Xi “institutionalized autocracy” had still been in place?

Yes. Dictatorship has several big drawbacks. And one of them is that it leads to a lower quality of decision making. One of the things that’s happened in China since Xi Jinping took over in 2013 is that he’s abolished collective leadership. My understanding was that under his predecessor Hú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛, you couldn’t really launch a policy initiative unless you have a consensus among all 9 members of the standing committee of the politburo. And Xi Jinping has really undermined that collective leadership so he’s replaced all of the members at the last Party Congress with loyalists. It’s very doubtful that there’s anyone that can really stand up to him. And he’s abolished term limits on the presidency so he’s going to really be there for life.

Speaking of the Party Congress, Xi scored a total victory by securing a rule-breaking third term and filling the Politburo with his loyalists. Also, he even escorted his predecessor Hu Jintao out of a highly choreographed meeting. What do you read from that?

Yes, if you look at the way that he humiliated Hu Jintao at the Party Congress by very demonstratively forcing him off the stage, he’s kind of indicated that anyone who tries to challenge him is going to be treated even more harshly. And so that means that if he launches a policy there’s nobody dare to say “Well this may not be such a good idea” or “Maybe we need to rethink this” and I think that’s really the problem right now — he makes a bad decision, and nobody can criticize it, nobody can change it.

This reminds me of your another article back in 2018. When Xi abolished the presidential term limits, you wrote, “China’s bad emperor returns.” Did you think back then things we see now were destined in a way?

Yes. China that was created by Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平 and lasted up through 2013 was authoritarianism but it was a very institutionalized form. What that means is simply that there were a lot of rules that leaders agreed to follow — you had term limits, you had mandatory retirement ages, you had rules about collective decision making about recruitment into the party and so forth.

One of things that’s happened since 2013 is that most of those rules have been stripped away and have been replaced by the sole decision making authority — one person. So I think that even without knowing what specific problems would arise, that’s not a good form of decision making, because nobody is so wise and so competent that they can really afford to make all those decisions and yet that’s the kind of situation that’s evolved. So I think it was possible to predict something like this well before it happened.

When an “emperor” dominates all the decision making, he gets to take all the credit if it turns out he has made the right call, but when wrong decisions are made, however, he doesn’t have a scapegoat to blame. Maybe that’s why some protesters put the blame on Xi himself this time. Would this omnipotent status Xi has projected become a double-edged sword that could force him to be responsive to people’s voices in the future?

That is a real problem for him — the fact that he’s not shared responsibility with other senior leaders means that he’s really the target of all the protests as you suggest. The classical Chinese “bad emperor problem” — if you have a good emperor, you can move quickly, you can do a lot of good things without constraints; but if you have a bad emperor that makes mistakes, then it’s a much worse situation.

Let’s elaborate on this “good emperor, bad emperor” theory. You mentioned that a dictatorship with few checks and balances on the executive power could do amazing things when the emperor is “good.” What happened during the early stages of the battle against the pandemic appeared to have served as testament to this argument: China was relatively successful, compared with most countries in the West, in containing COVID and saving lives. But what looked two years ago like a triumphant success has turned into a prolonged debacle this year. So, in your view, has the emperor changed for the worse, or was he actually a bad one in the first place?

I’m not sure the outcome of the COVID-zero policy necessarily tells you that much about whether he is a bad or good emperor. I think that is kind of the reflection of the rules of the system — no leader is ever going to consistently make really great decisions. That’s why you need to spread out responsibility among people, you need to get expert advice, you need to have a lot of discussion, including a broader social discussion, about what kinds of responses can people tolerate and so forth.

And you’re setting yourself up for failure if you don’t do that, and I think that again, the concentration of power in one individual made it very hard to change policy. So you’re right that the policy looked very effective in the first year of COVID. But it really needed to change, you can actually look at other countries — Australia, New Zealand and Singapore — all followed a zero-COVID strategy for the first year, but then they very quickly realized that that was not tenable and that they couldn’t endure these lockdowns indefinitely. So they decided that they would have to bear the consequences of reopening. And so they did. It led to higher infection and death rates, but that was the price that they were willing to pay.

In the early stage of the pandemic, you wrote that the crucial determinant in performance will not be the type of regime, but the state’s capacity and above all, trust in government. During China’s zero-COVID enforcement, there has been possibly the biggest expansion of the state’s capacity due to the mobilization of a huge number of hyper local officials. For the first time, it feels like the state is everywhere to lots of ordinary people, while it could hardly be felt in the past. But actually, people’s trust in the government has been declining. Why?

I didn’t say that the state’s capacity was a sufficient condition, it was a necessary condition.If you don’t have the state power and the health capacity to deal with the epidemic you’re obviously not going to be very successful. But in addition to that, you need to have the right leadership, making the right decisions that’s based on all of the available evidence, and I think that’s really what’s been missing in China’s case.

Obviously if you had a different decision made a year ago to open up China, China would have been very capable of doing that. I still think that because of this decision not to import vaccines you still would have had a very troublesome reopening — much more so than Singapore, Australia, New Zealand — but you certainly could have done it. So the state’s capacity by itself is not enough.

And social trust I think existed earlier on, but as the policy evidently didn’t work, it was creating huge social costs. I think that trust is very much eroded.

According to the Tocqueville effect, a revolution is likely to occur after an improvement in social conditions. And paradoxically, an autocracy is actually most vulnerable when it is least autocratic. Do you agree with that theory, and if so, do you think it would apply to China, too?

It’s possible that it’ll apply to China. The argument that Tocqueville made was that if you have an autocracy that then liberalizes and opens up a little bit. People’s expectations of freedoms advance faster than their actual freedoms. And therefore what seemed tolerable previously no longer seems tolerable because their expectations are much higher.

And I think that you could see a similar kind of dynamic coming out of what’s just happened with Covid — you had a repressive policy people protested. and the regime relaxed a little bit and people began to understand that maybe protesting works and so they’re more willing to do it again in the future if they’re unhappy about something. So it is possible that you’ll see something of that sort occurring in China.

The other thing that I think is important is not popular protest but within the leadership — support for Xi Jinping. I would think that people in a way that had been the most threatened by Xi are actually senior leaders in the Party who are being sidelined and humiliated like Hu Jintao and so forth. And up to this point they can’t really organize and they can’t complain given the way that Xi has centralized power. But anything that weakens them will strengthen the ability of his fellow party leaders. Such as, maybe this wasn’t such a great policy, maybe we should change course.

Of course, there’s no transparency in the regime so we don’t know whether these kinds of discussions are happening but it would be surprising if this didn’t also provoke more internal opposition within the Communist Party.

You mean like a coup?

It’s very hard, I think, to stage a coup. As I understand, the whole senior leadership including all of the members of the standing committee are under 24-hours surveillance. they’re really not able to talk to each other privately, so I think it’s very hard to organize an uprising. That’s what happened in the former Soviet Union when they got rid of Khrushchev and indeed after Stalin’s death. They eliminated Beria, the head of the secret police by getting together and forcing him out. But as I understand, it’s very hard to do that in China today because of the kinds of controls that have been put in place. But that’s why I think policy failure like this is important, because the people that have been obedient to Xi Jinping may not be so obedient in the future, after they’ve seen that he can fail.

Is China at risk of repeating its historical tragedies that happened when one leader centralized total control, like during the Mao era?

Yes I think that you’re already seeing that sort of thing happening. That’s really the long term problem with a dictatorship with no checks and balances. It might look like it’s doing well for a while but that’s a limited time, and then over time as the leadership makes mistakes, the regime looks worse and worse. I think China now is risking going down that path.

On liberalism and its discontents

Let’s also talk about liberal democracy. In your article, you contended that liberal democracy might still be the “end of history” after all. And some critics thought you were blind to liberal democracy’s failures. Meanwhile, you actually also analyzed and criticized the problems and weaknesses seen in Western democracies in your new book — Liberalism and Its Discontents. Can we say that you believe liberalism is indeed in crisis, and that is because of the complacency that set in with its successes?

You have to understand that liberal democracy has a lot of strengths over the long run. It could make big mistakes, the people don’t always choose the best leaders, they can be let down a lot of different paths that don’t look very good in the short run. But the thing about a democracy is that it has checks on power and it also has ways of holding leaders that screw up accountable. And I think that you’ve already seen that in the case of Donald Trump — you only have one term as president. This is a big strength of democracies that they can correct bad policies down the road. And that’s why I think that it’s still a much better system than autocracy.

After the midterm elections in the U.S., you wrote that it was a very good week. Sounds like you are very optimistic about the self-correcting capabilities in American democracy.

For a variety of reasons. I think that the “Trump wave” is over. He’s getting crazier and crazier. He just wrote a little post saying that they are to suspend all laws and rules including the constitution and declare that he’s president again. And I just think that’s not a good platform to run 2024. There will be a certain core of die-hard supporters that will like that, but I think that’s not a formula for getting reelected as president.

Liberal democracy has seen unprecedented challenges from both the right and the left over the recent years. Can it be preserved and adjusted skillfully, and if so, how?

I think there’s not a simple answer to that. Basically the people that want strong democratic institutions have to organize and mobilize in support of it, in the United States that really means voting.

So I think that given the way that the Republican Party has developed into an authoritarian Party that means they have to be defeated. And it’s gonna happen over several elections and at that point the Republicans will begin to realize that they’re never going to regain power if they don’t fix their course, so that’s one of the ways.

I think that a lot of institutions can be strengthened. We’ve got a winner-take-all voting system that I think encourages extremism and we could change some of those. So there’s a lot of different things that can be done about it so it’s actually quite a complicated set of changes that need to be enacted.

And last, what are your thoughts on the U.S.-China decoupling going forward?

I don’t think it’s possible to decouple fully. Because of the degree of economic independence.

I think what’s been going on is that the United States and Europe and other democratic countries have realized that they become excessively dependent on China for certain strategic goods, particularly in the technology area, but even things like medical equipment and drugs and so forth. And if there is a kind of intensification of the competition with China, that means that there’s a lot of volatility so there’s been an effort to reduce supply chain so that the U.S. and Europe and Japan are not as reliant on Chinese exports as they were previously. And I think that’s important and necessary and that’s going to continue.

And I think on top of that, a lot of western companies are feeling that as long as China maintains this COVID-zero policy their own operations in China are constantly going to be destructive, that’s why they would rather move those operations to other countries that don’t have a similar policy.

But that’s not going to lead to a general pushback of the relationship.

Will the bilateral relationships get less confrontational? With China as the No. 1 bipartisan target for America, some observers even predict there would be a military confrontation between the two countries.

China has said pretty openly that it wants to reincorporate Taiwan and it’s going to do it however it’s necessary and they have not ruled out the use of military force. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, everybody suddenly realized maybe when one authoritarian state says something like that we should take it seriously.

So I don’t think that the worry about Chinese aggression is really being driven from the west. I think it is being driven by China’s own behavior in the South China Sea and towards Taiwan and in general. So that’s really why I think we’ve had this deterioration of relations.

More on the protests in China from The China Project

- After the protests, a glimmer of hope — Q&A with Li Yuan

- The scary ‘foreign forces’ behind China’s COVID lockdown protests

- Photos: Chinese people organize anti-COVID-zero protests in New York

- The anti-COVID lockdown protests: The view from Beijing

- The protests that challenged China’s governance model