Is the Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act working?

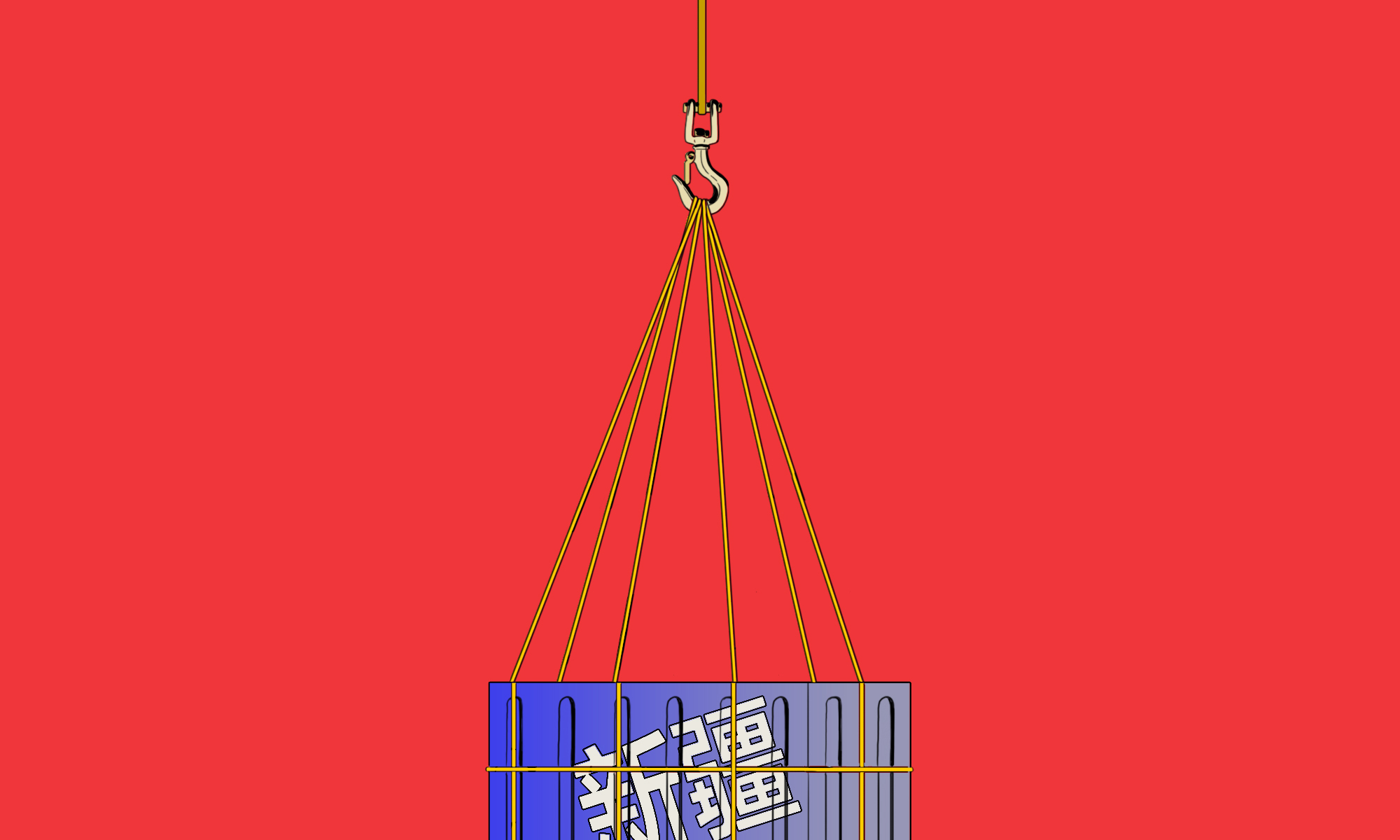

Half a year after Washington enacted a set of laws intended to prevent products of coerced labor from entering the U.S. market, supply chains in the solar power and apparel industries are snarled up, but it’s uncertain if the Uyghurs themselves have seen any benefit.

Vast numbers of goods worth hundreds of millions of dollars have been piling up at U.S. ports since the Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act (UFLPA) came into force in June 2022. One thousand shipments of vital solar energy components and other goods worth $266 million were seized by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and by the end of the fiscal year in September, there had been 1,500 seizures under the UFLPA valued at $500 million.

But the jury is still out on the success of this legislation that is intended to prevent goods tainted with Uyghur forced labor entering America’s markets. Since its launch amid fanfare and expectation six months ago, the UFLPA has delivered mixed results.

There are signs that supply chains are in chaos, as goods stack up at U.S. customs, and the mountain of bureaucracy is just too high for some companies to climb, while products are already being diverted to Europe. U.S.-based Compliance Week, describing itself as the “premier governance, risk management, and compliance resource” in its field, reporting on December 6, said “businesses are no clearer today on how to comply with the UFLPA.” Haley Byrd Wilt, an associate editor for the Dispatch, commented recently that customs officials’ implementation of the legislation, was “seriously limited.”

And while companies are facing these difficulties, it is not clear that there has been any benefit to the Uyghurs themselves. Some observers fear that that goods destined for America might simply be re-routed to other markets.

Canada’s Border Services Agency (CBSA) rejected the implementation of a presumptive assumption that all goods coming from Xinjiang were more likely to be tainted with forced labor, meaning that Canada could become a dumping ground for goods rejected by the U.S. The European Union’s proposed block on goods made with forced labor is hot on rhetoric but lukewarm on execution. The ban would rely on importers flagging up concerns, and could take two years before enforcement. Moreover, it does not compel EU members to adopt the same approach, and has no focus on Xinjiang but is targeted broadly at forced labor. In the U.K., despite minor tweaking of the Modern Slavery Law, parliamentary back and forth over the definition of “genocide” means that that Britain will be sitting on the fence for some time to come. Uyghur rights campaigners sued the British government for allowing imports made with slave labor in October 2022. They are awaiting a verdict.

Products of forced labor are still coming into the U.S.

Despite the UFLPA, as well as the Trump-era tariffs, imports from China into the U.S. increase year on year, and significant numbers of shipments from Xinjiang continue to slip through the net, much to the ire of human rights campaigners and Uyghur activists.

In August despite the U.S. government’s separate 2020 move to boycott all products connected with the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (Bingtuan), the quasi-military group originally set up to guard China’s Western frontier, now an immense corporate Goliath credibly accused of using forced labor, a tell tale “Bingtuan” label was spotted by a Virginia shopper buying “sweet dates” from China. Subsequent research by the Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP) found seventy such brands of dried fruit products being sold across America. Due to the strategy of “inter-cropping” red dates in the same fields as cotton in Xinjiang, both crops are being produced using forced labor, according to Nuzigum Setiwaldi, author of the report, who said it was “shocking that forced labor goods are still making their way into U.S. stores,” making ordinary consumers “complicit in gross human rights violations.”

Cotton is a big problem: Shein, the Chinese fast fashion ecommerce app that has taken the American market by storm was found to be selling clothing that is highly likely to be made from Xinjiang-produced cotton, according to laboratory testing commissioned by Bloomberg News. Shein has neither confirmed nor denied the use of Xinjiang cotton, rather continuing to claim regular audits of its supply chains and a “zero tolerance” policy for forced labor. Of the 2.7 million low-value packages entering the U.S. every day, most come from China, with Shein’s making a considerable share of the total. According to the Bloomberg report, the retail giant’s U.S. orders “skyrocketed 568%” in the first two years of the pandemic leading up to March 2022.

One of the problems is that most of Shein’s shipments to customers fall below an $800 value threshold that triggers reporting requirements to U.S. Customs, which Representative Earl Blumenauer, a Democrat from Oregon, described as a loophole “big enough to drive a 747 through” when he made a failed attempt last year to get Congress to tighten the customs rules.

Supply chain nightmares

The UFLPA differs from previous legislation— such as International Labour Organisation (ILO) protocols that have been in place since 1930 to prevent products of slave labor from entering markets — that put the burden on customs authorities to decide whether products are the result of forced labor. The UFLPA puts the onus on suppliers to prove innocence.

The Act is wide ranging, insisting that at no stage of production can there be any hint of forced labor. A company that might have relied on local auditors in the past to sign off on conditions in a factory making designer clothing for a Western fashion brand, can no longer do so. Companies in industries from cotton, tomatoes, and polysilicon to tech, life sciences, and mining are being required to dig deep into every layer of supply and present documentary proof that they are beyond reproach.

Despite the reams of guidance for importers, and the countless firms that have set up help lines, seminars, and consulting services to navigate the supply chain complexities, there are still a formidable set of hurdles awaiting companies large and small.

Dan Whitten, vice president of public affairs at the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA), conscious that much of the UFLPA legislation is aimed at the notoriously opaque supply chain structure within the polysilicon and solar panel industry, which has been proven to be complicit in Uyghur forced labor, was optimistic in June that “most companies should be able to meet the requirements of the UFLPA.” By the end of July however the SEIA was encouraging its members to avoid sourcing from the Xinjiang region altogether.

In order to prove that their products are clear of forced labor, every stage and every layer of the manufacturing process must be documented, a task that is nearly impossible to perform remotely. Myriad forms must be filled, checked, and double checked by the U.S. customs force, whose budget next year will be increased by $70 million and whose staff headcount will increase by 300 to cope with the influx. Border staff have so far not hesitated to demand proof right back to the raw material stage.

For some companies navigating the tangled web of requirements and the challenge of dividing up the indivisible at every stage of their product’s assembly is proving too hard.

The outdoor clothing and gear company, Patagonia decided to jump in 2020 before it was pushed and entirely moved its supply chains, as did LL Bean, Victoria’s Secret parent company L.Brands, and California-based women’s-wear maker Reformation, whose chief sustainability officer and vice president of operations, Kathleen Talbot, interviewed by Fortune in 2021 said: “Unfortunately, it’s not even as simple as just saying that you’re not going to source within the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous region (XUAR). The opaque nature of supply chains in the region means it really has to be the entire country.”

According to the United States Fashion Association benchmarking study released in July 2022, difficulties in performing thorough due diligence will force 85% of fashion companies to vote with their feet as a direct result of the UFLPA and reduce cotton clothing imports from China, while 45% percent plan to reduce non-cotton apparel imports.

Setbacks for America’s green energy plans

It may actually be easier for clothing companies to comply with the UFLPA than firms in other industries, especially the solar energy sector.

The stacking up at customs of polysilicon from Xinjiang spells a serious setback to America’s burgeoning green energy plans. Between June 21 and October 25, 2022, according to Reuters, 1,053 shipments of solar energy equipment had been seized, with Longi Green Energy Technology Co Ltd, Trina Solar Co Ltd, and JinkoSolar Holding Co being the main suppliers.

The writing had been on the wall back in February 2021 when Paul Wormser, writing in Solar Power World Online, warned the industry to prepare to decouple from the world’s largest supplier of purified polysilicon, and criticized the lack of preparedness for new legislation. “If you are in the business of importing solar modules, you likely need to start preparing now. That means avoiding using any goods from Xinjiang in all the products you’re importing to the United States,” he warned.

According to Tim Sylvia of PV magazine, the seizing of a solar module shipment from JinkoSolar soon after the enactment of the law in July, showed the difficulty of documentation of the origin of quartzite used in solar equipment, saying that “an untold capacity of U.S.-bound product shipments could now be in jeopardy.”

Already since June 2021, the difficulty in finding panels has decreased solar installations in the U.S. by 23% and delayed nearly 23 gigawatts of solar projects are delayed, largely due to an inability to obtain panels, according to the American Clean Power Association trade group. The industry faces a significant challenge in finding alternative sourcing for its solar panel industry, and prices of solar projects have risen by 30-40%.

American companies lobby to water down the UFLPA

Citing supply chain mayhem for products that rely on raw materials sourced from Xinjiang, companies such as Walmart, General Motors, Caterpillar, Amazon, Honeywell, DHL Express, UPS, and Intel, have been lobbying under the banner of the Commercial Customs Operations Advisory Committee (COAC), a group of major U.S. businesses, to water down the UFLPA.

This group has attempted, without success so far, to make data collection from vessel manifests confidential, and to blur public availability of shipping manifests.

But despite an optimistic Chris Magnus, former commissioner of U.S. Customs and Border Protection, saying at the end of October that the UFLPA had got off to a “remarkably good start,” implementation is still scrappy, commitment is low among many industry giants and much of the world has yet to be on board with the idea.

Beijing’s response

Beijing has hit out at the UFLPA claiming that most cotton picking is now mechanized and that no factory laborers are coerced. A spokesman for the regional government, Xú Guìxiāng 徐桂香 attacked the Act in June, calling it “an act of blatant robbery, zero-sum hegemony and Cold War mentality,” that would pose a “big threat to the security of global industrial and supply chains,” and would “seriously undermine a fair and just international business environment.” In the same article, Hamid Abdurehim, a researcher at the Xinjiang Development Research Centre, claimed that all employees in Xinjiang “enjoy freedom, equality, safety and dignity in their work, and a comfortable and reassuring life.”

But despite their protestations there is myriad evidence that Uyghur and Turkic workers in their hundreds of thousands continue to be victims of human trafficking in its worst form, and the constant threat of “re-education” or imprisonment for those who demur.

Omer Kanat, director of the Uyghur Human Rights Project initially welcomed the UFLPA, but has been frustrated at its implementation. He said there “are still very large, well known brands in the world that haven’t changed their supply chains.”

“The international community should have a coordinated action to make sure that China pays a price for what Xi is doing,” he said.

UPDATE: Just as this article was being published, the Uyghur Human Rights Project sent out a press release commending the U.S. Customs and Border Protection for detaining “several shipments of products bound for the U.S. market, as an enforcement action under the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act.”

UPDATE 2: Reuters, January 6: The United States and Japan on Friday launched a task force to promote human rights and international labor standards in supply chains, amid shared concerns about China’s treatment of Uyghur Muslims, and said they would invite other governments to join the initiative.