Philippines voids joint oil exploration pact with China

A mere week after a friendly visit to Beijing by the Philippine president, the country’s Supreme Court brought the gavel down on an “unconstitutional” 2005 pact with China and Vietnam to explore oil in the disputed South China Sea. The waters have only gotten murkier.

On January 10, the Philippine Supreme Court revoked a pact with China and Vietnam to explore oil in the disputed South China Sea one week after Chinese President Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 and his Philippine counterpart, Ferdinand Marcos Jr., announced efforts to revive similar talks. During his trip to Beijing in the first week of 2023, Marcos agreed to a slew of trade deals and even a memorandum of understanding over the South China Sea with Xi.

“The Philippine Supreme Court and legal system has taken steps to protect the country’s sovereignty when it sees the political leadership not standing up to protect it,” Pooja Bhatt, maritime researcher and author of Nine Dash Line: Deciphering the South China Sea Conundrum, told The China Project.

The new Supreme Court ruling was over a 2005 pact called the Joint Marine Seismic Undertaking (JSMU), which was signed between China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), Vietnam Oil and Gas Corporation (PETROVIETNAM), and Philippine National Oil Company (PNOC).

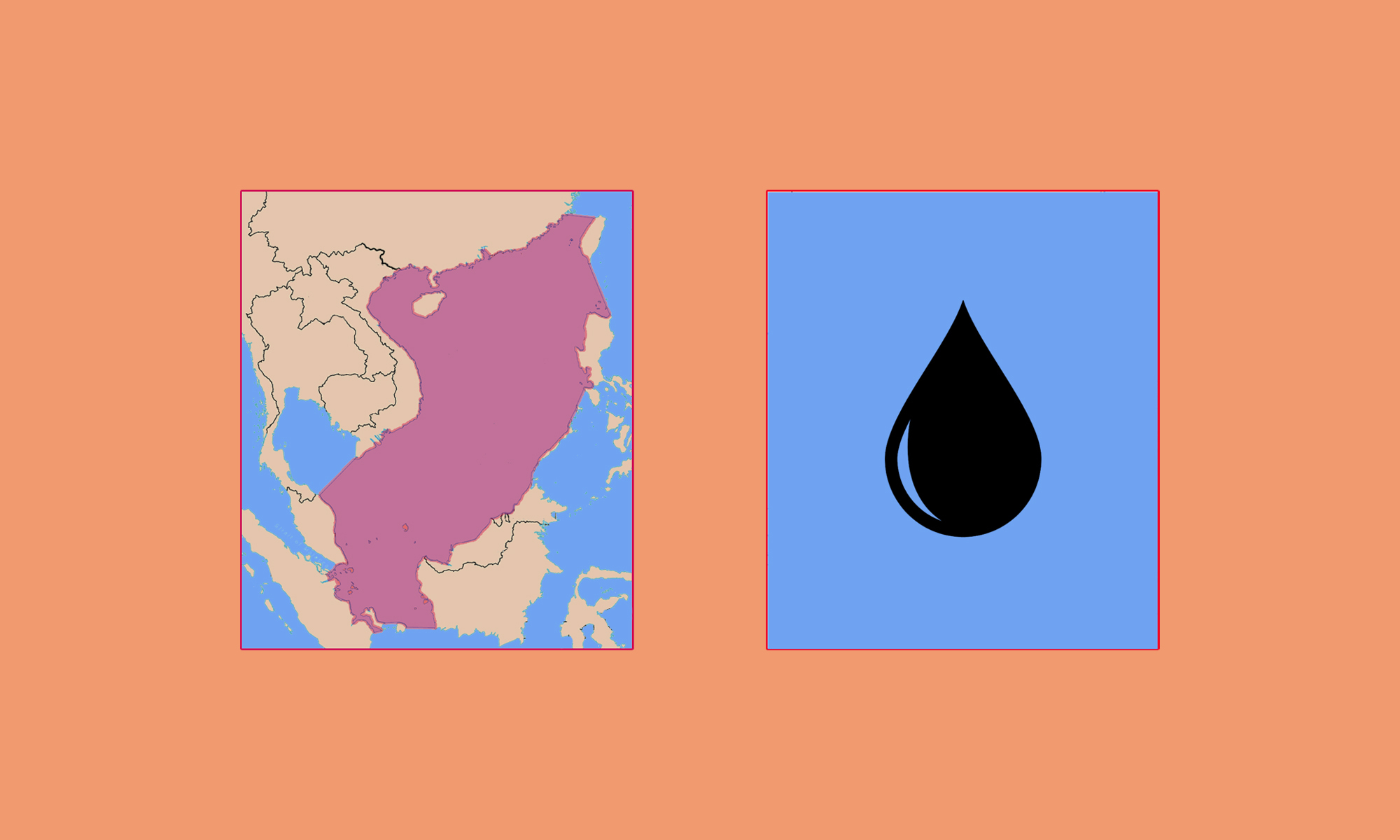

- Under the deal, the three nations would be permitted to conduct a joint seismic survey in the 142,886-square kilometer (55,168-square-mile) “agreement” area in the South China Sea.

- The agreement area includes the Spratly Island chain, a disputed territory that China, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan all lay claims to.

- Though the deal had lapsed in July 2008, the ruling also brings other proposed agreements into doubt.

The court’s decision by 12 of the 15 justices claimed that the pact violated Section 2, Article XII, of the Philippines’s 1987 Constitution, which mandates that the exploration, development, and utilization of natural resources has to be under the full control and supervision of the state. (A copy of the full court decision is not yet available. The Public Information Office released the summary of the ruling.)

- The JMSU had contradicted the domestic law, which stipulates that Manila may enter any joint venture for natural resources as long as 60% belongs to the Philippines.

- The court noted that the term exploration pertains to a search or discovery of something in both its ordinary or technical sense — essentially determining that the JMSU involves the exploration of the country’s natural resources, particularly petroleum.

The accord was controversial even when it was first signed on March 14, 2005, under then Philippine president Gloria Arroyo-Macapagal, during a previous “golden era” of relations with Beijing. Critics of the deal had claimed that it was not only unconstitutional, but also shrouded in secrecy and unfairly benefited China.

“When the JMSU deal was signed, the then-administrations of the Philippines and Vietnam saw it as an opportunity to resolve multiple issues — improving political, economic, and military relations with China, while seeing joint development of resources that were otherwise difficult in the resource-rich, yet disputed region of the South China Sea,” Bhatt told The China Project.

Since then, multiple iterations of the deal have been proposed and contested, largely due to tensions over Beijing’s hardening stance on its sovereignty claims in the disputed waters.

- The 2005 deal was signed before China asserted its “nine-dash line” claim to nearly the entire South China Sea, which it formally submitted to a United Nations body in 2009. An arbitration ruling from the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in the Hague concluded that Beijing’s claims were groundless.

- Philippine lawmakers also attempted to void the JMSU at the Supreme Court in 2008, but failed.

- The Philippines and the United States criticized China’s maritime efforts in the South China Sea last July, on the sixth anniversary of the Hague ruling.

- The administration under former Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte, Marcos’s predecessor, had signed a 2018 agreement with Beijing aimed at agreeing on terms for a possible joint oil and gas exploration in the disputed waters. But years of negotiations failed, mainly due to the aforementioned territorial disputes.

“The following years demonstrated that Beijing became politically and militarily aggressive with its maritime claims and rights much to regional and global disappointments,” Bhatt told The China Project. “Moreover, not only was 80% of the area mentioned in the deal a part of the Philippines exclusive economic zone (EEZ), but also the entire deal was kept under secrecy. The deal expired in 2008. Despite Manila winning the 2016 PCA verdict on the South China Sea against Beijing, the latter neither accepted the verdict nor backed down in its military aggression in the South China Sea.”

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

Just one week earlier, Marcos expressed willingness to revive failed negotiations for joint oil exploration with China in a meeting with Xi in Beijing last week.

- Both sides had “agreed to bear in mind the spirit” of the 2018 deal and “resume discussions on oil and gas development at an early date,” according to the official joint statement.

- China remains “committed to properly handle maritime disputes in the South China Sea…including the Philippines…and to actively explore ways for practical maritime cooperation including joint exploration,” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wāng Wénbīn 汪文斌 said today when asked about the decision, while nodding to the friendly tone of the Xi-Marcos meeting.

“The timing of this court ruling is noteworthy. Any international treaty or deal has to be ratified within the national jurisdiction to become operational. So while Marcos Jr. expressed his desire to renegotiate this deal with President Xi during his visit to China, the court struck down the legal provisions by calling it unconstitutional, creating a further blockade in the implementation of the deal at the domestic level,” Bhatt told The China Project. “Therefore, the Philippine Supreme Court and legal system has taken steps to protect the country’s sovereignty when it sees the political leadership not standing up to protect it. This step also claps back at China’s concept of ‘setting aside dispute and pursuing joint development’ in the disputed territories, instead of resolving it with its bordering nations.

“China, being the powerful party at the negotiating table more often than not, gets the better side of the deal, just as in the case of the JMSU deal, where state-owned CNOOC was the dominant partner,” Bhatt added.