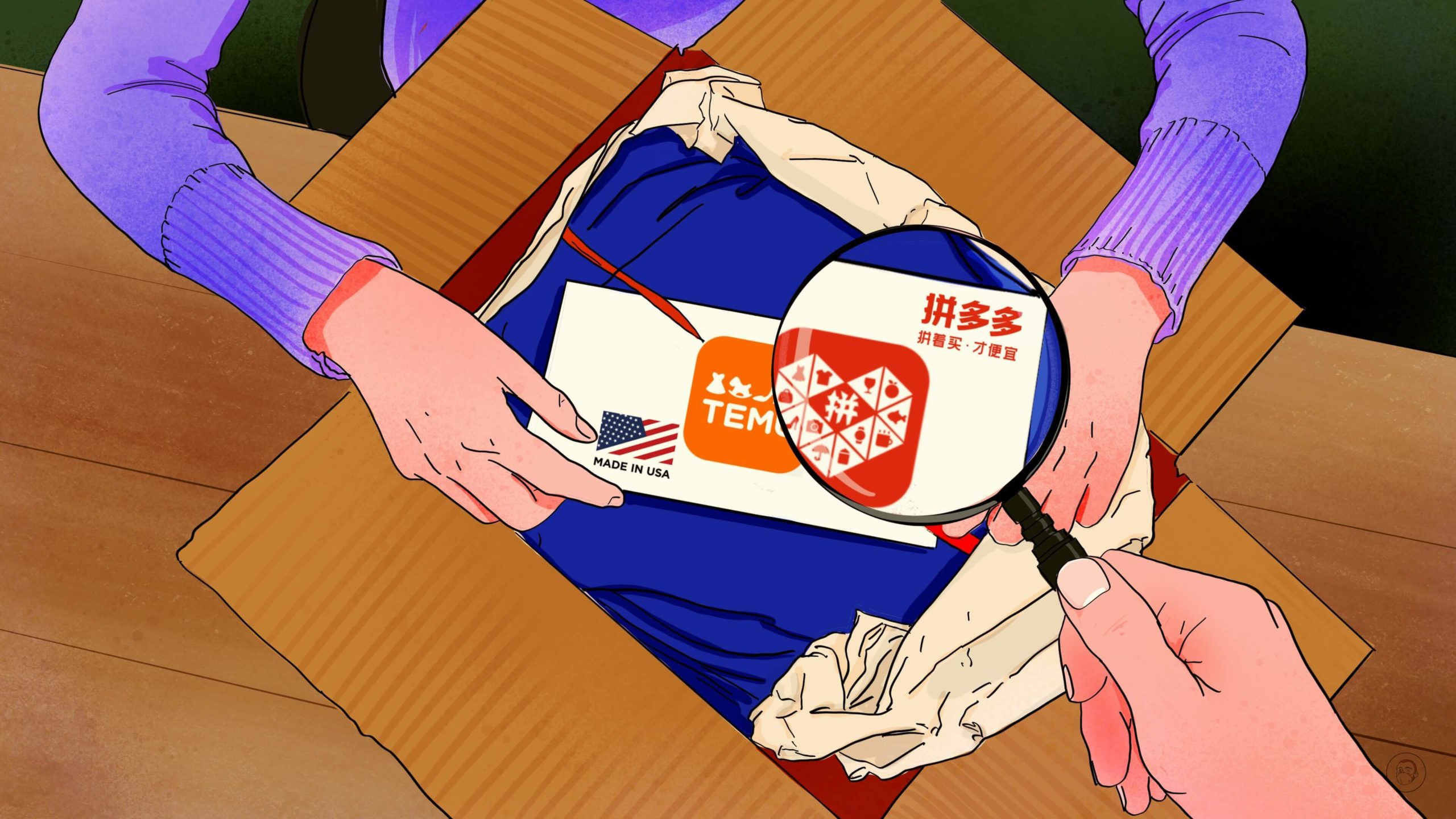

Can Chinese discount ecommerce firm Temu charm America?

Pinduoduo is China’s king of low cost ecommerce. Four months ago it launched Temu, a similar service for the American market. How sustainable is the new startup?

The name Temu (pronounced tee-moo) is an unorthodox abbreviation of “team up, price down,” a rough translation of Pinduoduo, referring to a business model of offering large discounts by selling products to large groups of customers.

Pinduoduo has earned the moniker “the price butcher” for its astonishingly low prices, and Temu is emulating this. Its main competition is the fast-fashion brand SHEIN, which launched in 2018 and rapidly became a favorite of young Americans, who spend at least $10 billion a year on the app according to some estimates. Temu still has some way to go though: Its projected gross merchandise volume (GMV) for this year is $3 billion, still only one tenth of the numbers SHEIN posted in 2022.

But Temu may catch up quickly, with Pinduoduo’s financial backing: The Nasdaq-listed parent company has a market capitalization of more than $132 billion, and had annual revenues in 2022 of more than $17 billion. And Pinduoduo is reaching into its deep pockets to fund Temu’s rise: Jiemian, a respected Shanghai-based media organization, recently took a sample set of Temu’s products, and discovered that similar items were 30% more expensive on Shein. (However, when The China Project attempted to replicate these findings, Shein’s offerings across a wide range of products were cheaper than Temu’s 80% of the time.)

However, unlike Shein, whose focus is primarily on clothing, Temu offers a bewildering array of products, more akin to Amazon. From home appliances and sneakers, to sex toys, security cameras, and Donald Trump 2024 memorial coins, Temu offers almost anything you might need, and plenty you don’t.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

Meet the parent

Pinduoduo is the brainchild of Colin Huáng Zhēng 黄峥, a software engineer who spent years at Microsoft and Google before returning to China. Founded in 2015, it had the fastest revenue growth trajectory of any company in history, hitting $100 billion in five years. It has expanded from its initial ecommerce service that focuses on selling cheap manufactured goods to rural and small town markets to offering marketplaces for small-scale farmers to reach urban consumers with next-day delivery of fresh produce, and other services aimed at rural communities.

Pinduoduo has recently been showered with awards, including from the UN’s Food & Agriculture Organization (FAO) for its technological innovations on the management of farming systems and emissions reductions, which FAO director-general Qū Dōngyù 屈冬玉 said were making significant contributions to sustainable agricultural development and global food security.

American investors have consistently backed the company, with many considering it a strong buy in the last quarter. As of January 27, Pinduoduo shares closed at $104.68, the highest price since July 2021. This strong start to 2023 continues a robust upward trend that started back in April of 2022. Such confidence came despite growing uncertainty throughout last year caused by U.S.-China geopolitical tensions, the ongoing Chinese government crackdown on tech companies, and perhaps most significantly, the prospect of Chinese companies being forced to delist from American exchanges. (Until December 2022, when the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) managed to secure access to Chinese firms’ accounts, Beijing had refused to allow U.S.-based auditors to investigate Chinese firms listed on U.S. exchanges.)

Risks: Labor abuses, quality concerns, and geopolitics

However, the picture is not all rosy for Pinduoduo. In recent years Chinese firms have increasingly found themselves singled out in discussions on labor rights, the environmental impact of fast fashion and low quality products (which abound on Temu), and data privacy concerns. Temu could be in for similar treatment, especially with the recent establishment of a Republican-led House Select Committee on Strategic Competition between the U.S. and the Chinese Communist Party.

It remains to be seen whether Chinese tech companies in non-strategic industries will receive the same scrutiny as firms like Huawei, and Temu seems less concerned with geopolitical headwinds and more with its market peers on the ground. But there is no mention of Temu’s Chinese ownership on the “about” page on its website, and press releases emphasize that the company is “Boston-based,” with no mention of China. In the current geopolitical environment, such sleight of hand is understandable — in December the U.S. Senate voted unanimously to ban Tiktok from government-owned devices, tightening the ratchet on the popular global app from Beijing-based ByteDance.

Risks: Troubled relations with suppliers and high ad spend

Some Chinese media reporting on Temu argues that the company’s setup leaves merchants with practically no agency: While suppliers provide the goods, Temu handles everything else, including pricing and order volume. This has led to merchants complaining of opacity in Temu’s communications with them, and of sharp increases in initial orders followed by very limited orders later on. It seems to many that Temu’s prices are unsustainably low, and if they fail to build a loyal user base of returning customers before prices inevitably rise, they have little chance of success. Temu clearly has a major challenge to put its relationship with its merchants on a firmer footing.

The main focus of Temu’s (and Pinduoduo’s) spending is on marketing. Advertising is central to Temu’s business model (something which founder Colin Huang presumably learned from his time at Google), and it ran over 1,000 ads on its platforms in its first two months, many more than rivals Shein and AliExpress 全球速卖通. According to China tech news site Pingwest, Instagram currently accounts for 30% of Temu’s new customer acquisition, making it a dominant medium for reaching potential users.

Risks: The culture gap

However, the results of Temu’s marketing campaigns do not seem to be commensurate with the spend: Scroll through Temu’s Instagram account, and its brand strategy comes across as simple and somewhat naive. The captions are littered with typos and inaccuracies that makes one half suspect that they have been mangled by a translation tool, or generated by a chatbot. One recent Instagram caption read “Twenty-four Seven, all about you. Temu did. Here is the saying. Mention the people you cursh on in comments of this post” [sic]. After The China Project reached out for comment, Temu deleted several of its posts.

Risks: Delivery and return problems

Temu does not yet operate warehouses in the U.S., and most goods are sent from China in individual packages for individual customers or in small bundles for small groups of customers.

With this system, delivery times are currently around two weeks, about double the time Shein takes, and much slower than Amazon, which offers deliveries to many American markets in less than a day.

Temu’s after-sales service is also currently weak. Reports from customers interviewed by The China Project and comments on forums such as the Better Business Bureau and Temu’s social media feeds are mixed: for every positive review at the astonishing value for money, there is a sense that the prices were too good to be true because the goods took too long to arrive, could not be easily returned, or were not what the customer had expected.

The opportunity: The everything store for the coming recession?

China (and Chinese companies operating in other Asian countries) is still the world’s source of cheap manufactured goods and this is not going to change anytime soon.

Inflation and the prospect of a recession haunt the U.S., and the strong job growth of the pandemic era has come to an end. In this environment, consumers are increasingly seeking out low-priced goods, and Temu might be the company that is best suited to sell to them.