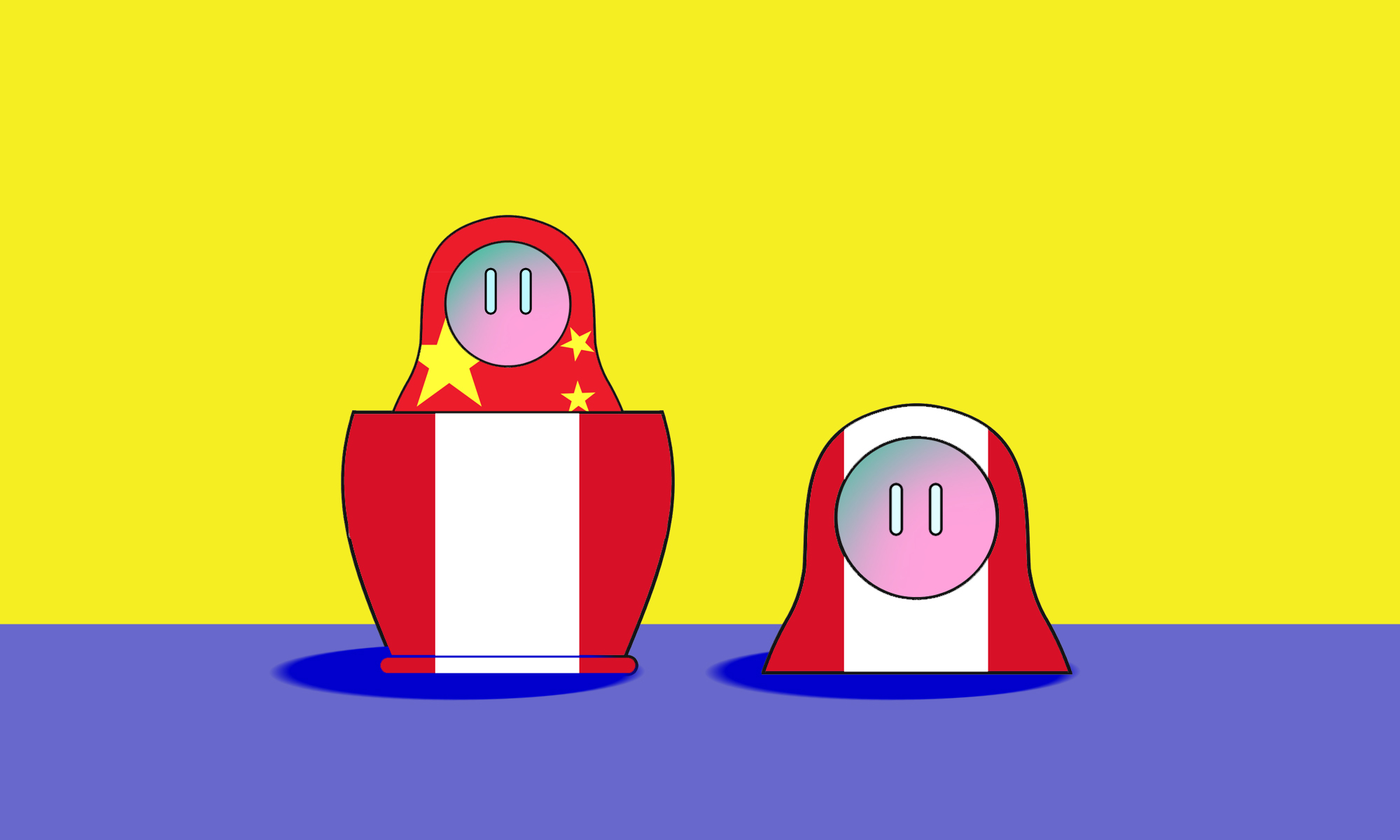

Amid political turmoil in Peru, China attempts business as normal

China is Peru's largest trading partner. Within this South American country, Chinese corporations have an opportunity to change public perception about the benefits — and drawbacks — of "Chinese influence."

In the southern Peruvian region of Apruímac, around 4,000 meters above sea level, lies a Chinese-owned copper mine. Producing two percent of the world’s copper, Las Bambas has been plagued by controversy and disruptions since its inception. And last week, the embattled mine was interrupted once again.

On February 1, MMG Ltd. (a subsidiary of China Minmetals H.K.) began a “period of care and maintenance,” interrupting normal production. The cessation of typical operations at Las Bambas is nothing new. Due to the constant protesting of indigenous locals, Las Bambas has suffered more than 400 cumulative days of interruptions. But this recent one, for the first time, wasn’t related to the mine itself: it was because of an ongoing political crisis nationwide.

Since December 7, Peru has been rocked by political unrest. On that day, former Peruvian President Pedro Castillo attempted to dissolve Congress and rule by decree. However, without the backing of Peru’s military or police, he was promptly impeached, and his vice president, Dina Boluarte, was sworn in. Castillo is from an indigenous and peasant background, and many of the protesters view his ouster (and his replacement’s subsequent rightward shift) as a sign that their country’s democracy does not have their best interests at heart.

Protests have erupted around the Andean nation and are still ongoing. In cities and towns all over Peru, aggrieved protesters are marching for political change. They have set up roadblocks and taken over airports; in one case, a politician’s home was set on fire. Police have responded, in several cases, with deadly violence, leaving at least 49 protesters dead. In addition, one police officer has been killed and 10 others died after being unable to reach hospitals due to roadblocks set up by protesters.

In the midst of all this chaos, China is Peru’s largest trading partner. While companies like MMG, have been forced to take economic hits, neither the Chinese government in Beijing nor the embassy in Lima have commented on the current affairs.

“This silence is consistent with China’s policy of non-interference in the domestic affairs of sovereign nations,” Margaret Myers, the director of the Asia and Latin America Program at the Inter-American Dialogue, told The China Project. “And so I wouldn’t expect any real comment on the situation and no indication either of strong support [for Boluarte or any other political figure] until things are resolved.”

Examining China’s relationship with Peru

On April 28, 2009, China signed its first free trade agreement (FTA) with a Latin American country — Peru. Since then, the relationship between the two nations has grown steadily. Just 10 years after signing the FTA, Peru also signed on to the Belt and Road Initiative, resulting in China becoming Peru’s largest trading partner. This is perhaps why former president Pedro Castillo chose China as his first official embassy visit after being elected.

According to the Chinese Embassy in Peru, the trade volume between the two countries exceeded $37 billion in 2021. However, when it comes to foreign direct investment, China is not the biggest investor in Peru’s economy (Peru’s largest foreign investors are Spain, the rest of the EU, the UK, and the U.S.). There is one sector, though, in which China does represent one of the most important investors — mining.

Mining is one of the biggest sectors making up the Sino-Peruvian relationship. Around 2016, China held up to 30% of Peru’s total mining investment portfolio. In addition to Las Bambas, Chinese-owned companies such as Shougang Hierro, Minera Shouxin, Jinzhao Mining, and Chinalco have invested $577 million between January and November 2022 in mining activities.

Many of these Chinese-owned mines have attracted controversy. Additionally, projects ranging from ports to roads have also caused problems for local communities.

Mining is one of the biggest sectors making up the Sino-Peruvian relationship. Around 2016, China held up to 30% of Peru’s total mining investment portfolio.

In January 2020, the CCECC Peru Consortium won the tender to build the Cusco-Madre de Dios Corridor, a road which serves to connect the region of Cusco with the more remote Amazonian region. However, in addition to corruption issues on this project, the road has also been criticized for its potential harm to indigenous and uncontacted peoples who live nearby. Experts have warned that this corridor may put the lives of those living nearby at risk.

Controversial Chinese infrastructure projects in Peru are not only limited to mines and roads. In January 2019, Chinese state-owned COSCO Shipping Ports Limited signed an agreement to become a 60% shareholder of the consortium which owns a mega-port two hours north of Lima. When completed, the Chancay Port will be the first mega-port to be built with Chinese investment in Latin America and aims to facilitate trade between South America and Asia.

Despite the lofty goals of the Chancay Port, according to some reports, locals in the community of 60,000 have taken issue. Some community members have reportedly complained of the port hurting the local tourism industry and of the construction causing cracks in their homes.

However, Cynthia Sanborn, a political scientist at Universidad del Pacífico in Lima, views the Chancay port as a potentially positive example of Chinese investment.

“Peru is a country with an economy that depends heavily on exporting to the rest of the world, and our port infrastructure is seriously deficient,” she said. “For decades now, we’ve needed larger and more modern ports…so having a new modern deepwater port would be a potentially terrific boost for Peru’s economy with a high expectation for employment of local people.”

Sanborn believes the negative reports may be overblown.

“The number of families that have to be relocated to build the port appears to be relatively small, and as far as I know, they are being relocated in line with [Peruvian] legislation.”

The Chancay Port may be fully operational by 2024, as journalists and NGOs continue to monitor the situation on the ground.

Protests against foreign projects

There is one case of infamous Chinese investment in Peru whose controversy is apparent and less debatable. There is an iron mine in the Peruvian region of Ica that is owned by Shougang Hierro Peru S.A.A., a subsidiary of Shougang Group Co., Ltd. The mine began operating in Peru in the 1990s. Since then, Shougang has suffered from perpetual protests due to issues such as low salaries. Demonstrations surrounding the iron mine have even led to one protester being killed in 2015. Lax safety measures have also caused deadly accidents.

In addition to Shougang, various other controversies involving Chinese investments have led to at least 35 legal actions being pursued against Chinese companies in Peru as of June 2022, according to a lawyer from Peru’s Ministry of Transport and Communications.

Needless to say, China is not the only country with projects in Peru causing controversy. European and North American projects have also instigated indigenous protest and raised concern from environmental NGOs. To name a couple, these include Amazonian tribesmen killed while protesting against a Canadian oil company and workers protesting at an American-owned mine in Arequipa (a Japanese company owns a 20% share of this mine). Furthermore, a Spanish company, Repsol, is responsible for one of the worst environmental disasters in Peru’s recent history.

This suggests that Chinese companies in Peru may be no different than Western companies with regard to their impact on Peru’s environment and Peruvian human rights. To this point, one 2013 study found that Chinese mining firms’ degree of compliance with local regulations in Latin America is comparable to that of their counterparts from other countries. More recently, a 2022 study by the Solidarity Center and Peru Equidad also found that Chinese companies operating in Peru do not behave much differently than Peruvian companies or companies from other countries.

Chinese companies operating in Peru do not behave much differently than Peruvian companies or companies from other countries.

While Myers agrees that, historically speaking, what we see from Chinese companies may not be as bad as what we have seen from Western companies, she believes that with Western companies, local communities at least have some avenues to appeal for change, through established channels and mechanisms. However, NGOs may have a more difficult time directly affecting Chinese company behavior.

“International NGOs working in conjunction with local NGOs have been effective in shaping company behavior and decision making…but it’s sometimes harder to engage in the Chinese case,” Myers told The China Project.

Myers believes this is because China’s state-owned companies are beholden to different priorities, as put forth by the Chinese government.

Sanborn agrees that civil society organizations play an important role in countries like Peru, but does not believe that their presence significantly impacts behavior.

Changing public perception?

Putting aside the differences between Chinese and Western companies, if China wants to grow its influence in Peru, its may need to make efforts in the arena of public opinion, as research suggests that controversial investments in Peru can negatively impact Peruvians’ opinions on China.

A 2021 study by Kerry Ratigan, an American political scientist, suggests that rural Peruvians are less likely to trust China if they live close to Chinese investment (though Peruvians’ attitudes toward China are generally positive). However, Ratigan also posits that Peruvians who live close to Chinese investment that has benefited the local community may be more likely to trust the Chinese government.

Sanborn, though, warns about the volatility of public opinion in Peru. She points out that the racist attitudes among some Peruvians may influence public opinion polling.

“Racialized attitudes about ‘los chinos’ in Peru can influence public opinion in ways that are not related to foreign relations or trade,” she said. “Despite having a large and fairly well-respected Chinese descendent population, we unfortunately also have a lot of prejudice running through society about Asians.”

As U.S. prestige and influence continues to decline in Latin America, China may have an opportunity to fill the void. And if the Chinese government is looking to positively influence public opinion, the case of Peru may illustrate that positive investment that benefits the local community can result in positive attitudes toward the PRC. Whether it is at the Chancay Port or their copper mines, by adhering to the best corporate global standards, China has an opportunity to raise their standing in the region.