Lou Reed’s posthumous book ‘The Art of the Straight Line’ reveals a tai chi master

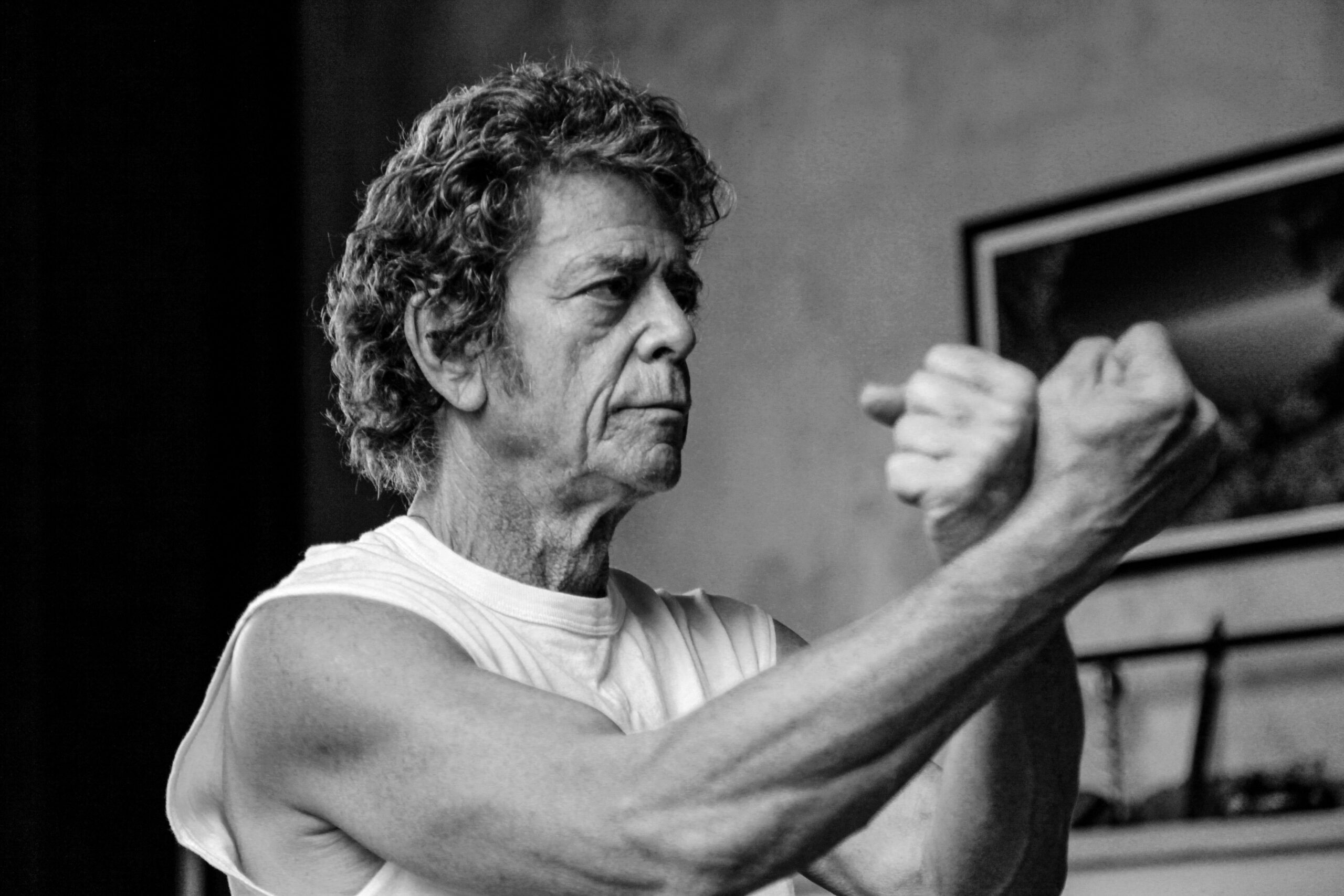

Lou Reed was a visionary rock ‘n’ roll musician. He was also a dedicated practitioner of the ancient Chinese martial art of tai chi. That passion is the subject of The Art of the Straight Line, a posthumous collection of Reed’s writing on tai chi and conversations with friends and teachers that is the subject of this conversation with Laurie Anderson and Stephan Berwick.

“Not to get too flowery here, but I want more out of life than a gold record and fame. I want to mature like a warrior. I want the power and grace I never had a chance to learn…tai chi puts you in touch with the invisible power of — yes — the universe. The best of energies become available, and soon your body and mind become an invisible power.”

— Lou Reed, from an original letter published by The New York Times, October 25, 2010

Lou Reed was a founding member of the legendary rock band The Velvet Underground, and had a groundbreaking solo career that spanned five decades until his death in 2013. His many collaborators included Andy Warhol, John Cale, Robert Wilson, and Metallica. Reed’s influence continues to be heard in the music of every generation of artistic outcast that yearns for a sound that reveals tenderness underneath a rough exterior.

Some might be surprised, however, to learn of Reed’s other great passion: tai chi (太極拳 tàijí quán), a martial art that originated in China some 2,000 years ago. Reed’s dedication to the form began in the 1980s and continued all the way to his very final moments in 2013, as you can read below.

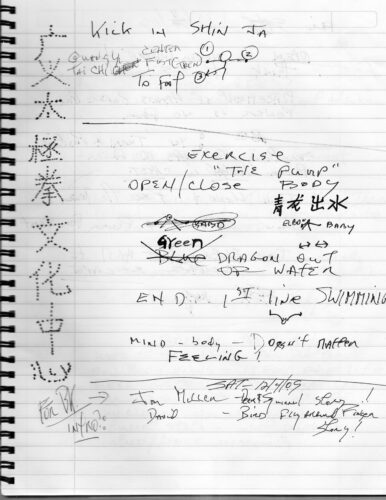

Before Reed passed away, he left behind scattered notes about tai chi for a book. His wife, the musician and artist Laurie Anderson, worked with Stephan Berwick, Bob Currie, and Scott Richman to bring together his writings and create The Art of the Straight Line. The book shares the story of Reed’s physical, mental, and spiritual journey through the challenges of tai chi, and is also something of a how-to guide for aspiring tai chi practitioners.

I talked to Anderson and Berwick about the book last week. This is an abridged, lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

—Susan St.Denis

The China Project: How did you two first meet and get to know Lou Reed?

Stephan Berwick: I first met Lou in 2003 at a large Chinese martial arts event out in California with his teacher Rèn Guǎngyì 任广义, who insisted that I come with him. He really wanted me to meet Lou. Master Ren, as we all called him, was just getting started teaching Lou, and right off the bat I saw what kind of relationship they had.

Laurie Anderson: We met a few times, but we were in different sorts of circles. When you think of the New York art world, art music world, there’s about 25 different circles in there. You can revolve around your own little circle, in a little eddy of your own, and never meet other people within their little so-called art world. Our first date (I didn’t realize it was a date at first) was at the Acoustical Engineering Society. We went to see two microphones. We both loved microphones, and we went to look at them. We were together from then on.

Lou began this book in 2009, but unfortunately was unable to finish it before his passing. What led you to take on the task of picking up where he left off and bringing this book to completion?

Laurie: My experience after he died was pretty much like a 15-story building fell on top of me. I was suddenly responsible for the whole estate, for the music — for everything, and being the one who had to make all those decisions. So, I did that very gradually, and hired a couple of people to help me.

The book was always on my mind, but it wasn’t number one. It took us maybe three or four years after his death to kind of go, “All right, let’s finally do the book. Let’s try to gather these pages up and see what we can make of it.”

There wasn’t enough for a book, in terms of pages; there was enough for a pamphlet. So we decided to expand it and talk to his friends, to his fellow practitioners, and to his various teachers of all kinds, and kind of make a collage…it was always for us. The idea was not to make a portrait of Lou, but it was to inspire people to do tai chi, period. It was going to be a handbook.

Stephan: Lou was just overwhelmingly passionate about promoting this particular piece of Chinese culture. He was a ‘Kung Fu head’! He loved Chinese martial arts, like so many people do all over the world. But he didn’t come to it like a Sinologist. He didn’t come to it like so many folks of a certain age, maybe the Gen X age, who, when China first opened up, ran over to China to study the language and taste an exotic new world. He really came to it as a brilliant artist who was open and hungry for something to improve himself.

He wanted the world to know, to understand, what this is, not on the mystical side, but on just the practical side. He seemed to understand what is powerful about this piece of culture. And whether you speak the language, whether you have immersed yourself in the culture socially or personally, it doesn’t matter, you can still get something out of this rich and deep art form. And that was the message he wanted to get out there. That’s honestly what fueled us to get this book done

You mentioned that he would often say that tai chi was more important to him than his music, and I think that’s something that might shock a lot of his fans. Did you ever have a moment, in the process of working on this book, where you learned something surprising about Lou that you didn’t know while he was still with us?

Laurie: Well, first of all, that thing about being more important than music, that’s a bit of a misquote, I think. In the last three or four years of his life, he decided to do tai chi every day. And he was still doing a lot of music. But he did say that tai chi was his priority at that point. But of course, that’s the end of his life.There were many other times in his life where he had to find a balance between doing this thing, because he was a really busy performer and person. It takes time to learn these things and to work on them, which he really wanted to do. So, I would not say it was more important than music — no way. He was a writer, and he loved all of those things. They influenced each other. His writing influenced tai chi, his tai chi influenced his writing, and his musical style, in particular his stance, and the way he held the guitar, and the way his feet were firmly planted.

When I look at some of how he did some of the forms, the relaxation in his hand, I think, “That’s a guitar player’s hand.” I just saw him doing tai chi when I saw him play guitar. It was really about the way he was holding the instrument, the way he held his stance as a musician. And, of course, when Master Ren came on tour, that was even more obvious when you saw Lou standing there, you thought, “That’s the way a martial artist stands.” It was such a shocking and beautiful thing to see that in his body, in his hands, his arm, his back, that was his training. It was astounding.

Stephan: Yeah. One of the people we interviewed in the book — and we interviewed about 80 people from all walks of life who either knew Lou very well, taught him, or who trained or worked with — one of the most insightful personalities we spoke to was Chén Bǐng 陳炳. Chen Bing is possibly the most famous of the younger Chen Family Masters in China. We’re talking about the family that created tai chi, born and raised in the founding family village of tai chi, Chenjiagou, Henan Province.

Chen Bing is a very interesting because of the wide variety of folks he’s taught and worked with. In our interview, he talks about how he worked with other musicians in some form or another in China. And he said that what he saw in Lou, seeing Ren Guangyi on stage with him performing in all types of venues, in the David Letterman Show and on Top of the Pops — very commercial, mainstream venues — he said it always struck him how Lou and Ren were able to bridge a lot of gaps between the freewheeling feeling of Western rock music with this more strict, traditional kind of rules-based discipline of tai chi that goes back very far.

The whole East-West thing, how do you combine something like this? How do you combine very rich rock with high poetry behind it with the performance of tai chi, and very traditional tai chi, not interpretive tai chi?

Chen Bing, thought that was extraordinary. He described how he had never seen that happen before. For him, it was like a big pioneering act, of seeing these cultures — actually two expressions of two very different cultures — somehow coming together in a way that just makes perfect, perfect sense. That’s another important message. We talk quite a lot about what is multiculturalism? How does one culture affect another culture? How does one culture help another culture? For me, this is where Lou was going with this, and his active promotion of tai chi is a testament of that.

How did Lou meet Master Ren, and what was their experience working together? What was the impact of Master Ren on Lou’s life?

Laurie: I have to say it was really pretty crazy because I had been going to other schools with Lou since ’92 when we met. We’d been experimenting with different things, but eventually I thought, you know what? I don’t want to do every single thing my partner is doing and follow him around. I asked around, and I can’t remember who told me about Master Ren, but I started going to his class on Lafayette Street. It was probably only a couple of months after that that I said to Lou, “I hate to say this, but my teacher’s better than yours, and you’d better come and check this guy out.” And he did. I will never forget when they met. I will never forget…Lou just came to the classroom, went, “Wait a second. This is the real thing.”

And then I was a third wheel. I think it was easier for Master Ren to have a friendship with a man than a woman, for sure. He’s very egalitarian in terms of his class. In fact, most of his students now are women, and he treats women very, very respectfully. And he challenges us to do things. He is not at all patronizing, not for one second. But I did feel like the third wheel, I went slinking off, and I didn’t really return to the class. Once in a while I would go with Lou, around 2006, but the bonding between them was so…they became brothers.

Martial arts presented challenges to Lou which he had to overcome. How did this reflect in his later life, and what changes did you notice in him?

Laurie: He used it as a way to help him get old, as a way to help him die. He was fierce. That was the way he chose to do that. He died doing martial arts, literally. I was the only one with him, and I saw that, him doing “cloud hands” as he died. That’s an amazing thing, that it takes you right to the last moment of your life, you trusted it that much. It becomes so much a part of you that it is like breathing.

But it was also his weapon: he used meditation as his weapon. We’re going to put out a record, Hudson River Meditations, that will be a kind of compliment to the book. And that’s going to be coming out hopefully at the end of the summer. The record will have what I had hoped the book would have, which is a poster of one of the forms. After all, what’s a how-to book without a step-by-step showing you what to do?

Stephan: Lou got into martial arts around the early ’80s, so it actually goes back pretty far. His second teacher, Leung Shum, had been a longtime pioneering teacher of Chinese martial arts in New York. Lou first studied Eagle Claw under Leung Shum, which involved a lot of the gymnastic stuff that Laurie talked about earlier. But he also taught a form of tai chi, Wu-style, that’s very popular in Hong Kong, which is where Leung Shum is from. He’s still around, thankfully, and was one of the first people we interviewed.

At one point Leung mentioned to us, “Oh yeah, I remember Lou recorded a song about tai chi.” And we were like, “What? Are you…” It was early in Lou’s training. When Leung mentioned that to us, it kind of freaked us out. Then a few years later, one of our co-editors, Scott Richmond, while conducting research in the Lou Reed archive at the New York Public Library, found the song. It’s called “Invitation to tai chi,” and — you’re going to be blown away when you hear this — he actually sings about his very first Chinese martial arts teacher, Peter Morales, who by the way, was one of the very first Americans who trained in China back in the early ’80s in Nanjing. That song is an anchor to so many things, so many periods of his early odyssey through Chinese martial arts.

What do you hope this book can show people about China, beyond the political sphere that we tend to look at when we think about the country?

Stephan: We hope to show the world that there are certain aspects of Chinese culture that are accessible to everyone. Tai chi, a couple of years ago, was finally placed on the UNESCO tangible cultural heritage list. It took a lot of effort from mainland China to do that. But it was something that I was happy to see because one of the big misconceptions about trying to delve into any other cultures is that if you don’t speak the language, if you don’t live there for 10 years, if you don’t marry someone there, you’re never going to be brought inside. You’re always going to be an outsider.

But with Martial arts that’s different. Tai chi has a universal accessibility and appeal that I think people just don’t fully realize. We hope this book will show people how accessible it is, how you can have a piece of this cultural heritage. And for many people, and even for many China experts, they often describe tai chi as perhaps the one art form and cultural expression from China that most represents the Chinese psyche. It is something powerful that everybody can and should be doing.

Laurie: And of course this is an American interpretation, but I think that one of the things that Lou and Master Ren shared in terms of just personality traits, and you could say in very broad strokes, are things that Americans and Chinese share: A very practical approach to the world, one in which you can improve yourself. These are both very basic to our cultures.

We’re not the French or the English. We are much closer to Chinese people in this…I mean, I’m talking obviously in ridiculous broad strokes, but I feel that the times I’ve been to China, I feel a rapport that is down to earth…And I see that in the brotherhood of Master Ren and Lou. I saw that sense of the physicality, the body, the practicality, the work ethic, it was very, very much there in that friendship. That’s something to be celebrated in the relationship between our two cultures; it’s very important to see that. This is a gift in many ways, not just to Lou’s fans, but to Chinese culture.

This is an American artist who fell in love with Chinese martial arts and Chinese culture, and wanted to bring it to the world through his music. He wasn’t ever pretending to be an ambassador, but he wanted to say, “Here, look what I learned from this, and it’s my spin on it. So, it’s not a perfect spin, but I fell in love with this, and I want to show this to you.” We’re very proud of the book, and from that point of view, it feels to me very much like a gift to all of the ideas and practices that come from China.

Stephan: There’s a very high level of elegance to any high art form. There’s elegance throughout all of this — Lou’s own elegance, the elegance of tai chi, the elegance of Master Ren. These are things that anybody can relate to and anybody can hold up high. And that comes with a deep, mature development of these art forms. There’s an elegance there that is so universal, it’s almost beyond culture.