The man behind the protests at Pakistan’s Belt and Road hub at the port of Gwadar

Resentment at the Chinese-funded port development at Gwadar in Pakistan’s Balochistan Province has been building for several years and one man is leading an ongoing protest movement.

Surbandan is a town on the Arabian Sea shore in Gwadar District, Balochistan Province, Pakistan. It’s 25 kilometers (15 miles) from the main port town of Gwadar, where China is developing a port and transport infrastructure.

One day, at the beginning of 2021, locals spotted five Chinese trawlers in the sea when they woke up in the morning. The ethnically Baloch residents, many of whom depend on fishing for their livelihoods, gathered together to protest the arrival of Chinese trawlers. The protests were led by Maulana Hidayat-ur-Rehman, who is in his late 30s and was then a little-known politician from Surbandan. By the end of the year, he was organizing regular protests, and he has now emerged on the national scene in Pakistan.

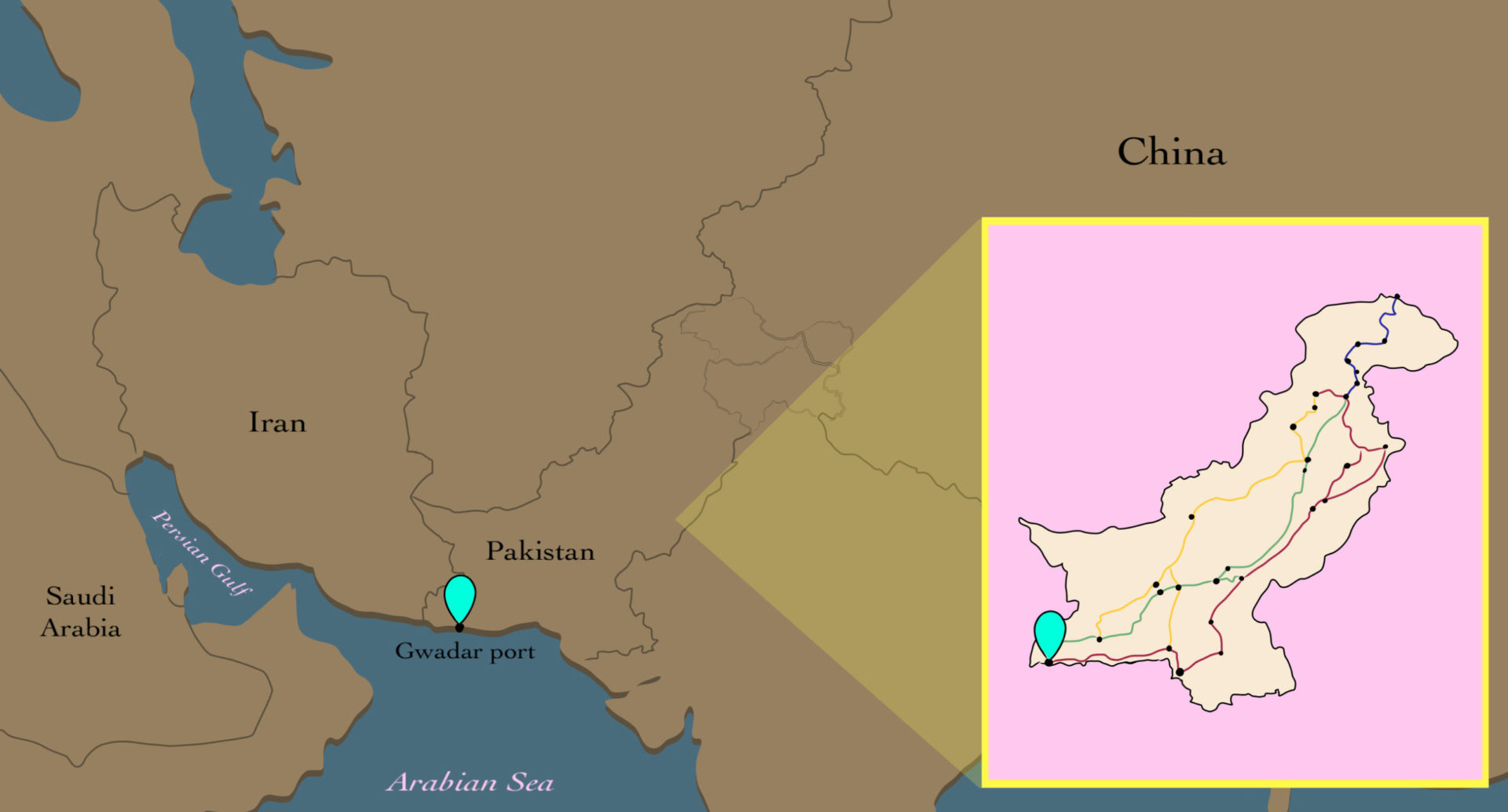

The port town of Gwadar, perhaps better described as a harbor next to an impoverished village, is a key node of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which makes up the backbone of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Pakistan.

CPEC, valued at $65 billion, is a massive bilateral project between China and Pakistan to improve infrastructure within Pakistan for better trade with China and to further integrate the countries of the region. For China, the project offers a direct connection to the Indian Ocean at Gwadar, straight from the western province of Xinjiang.

But many locals do not see the upside.

“We have been protesting for one and a half years in Gwadar for our basic rights,” said Anwar Ali Baloch, a local shopkeeper in Gwadar. “Although Gwadar is dubbed as the jewel in the crown of the CPEC, we have been crying for our basic and constitutional rights such as health, education, electricity and water rights, among other things, which we lack to this day.”

“In Gwadar, ever since the announcement of CPEC back in 2015, the issues of people in the port town, instead of dwindling, have further compounded,” recalled Maulana Hidayat-ur-Rehman, the protest organizer, speaking to The China Project. “While traditional representatives had kept mum over the issues of the people, and I knew there was a political vacuum, too, I stepped in to become a voice of the people. Since then, people have come out to stand up for their rights in the port town along with me.”

Maulana is right to assert there are many people who stand behind him. In 2021, when he first came out to protest, there were tens of thousands of people in the port town he led to demand basic facilities and demands.

At the time, one of the protestors’ demands was to put an end to “unnecessary checkpoints” that had sprung up in and around Gwadar following the announcement of CPEC in 2015: for many locals, an invasive security presence has been the main noticeable effect on the ir lives of the Chinese investment projects. .

Displaced fishermen

“I have gone to Maulana’s protests,” said Mujeeb Baloch, a local fisherman from Gwadar, “because he raises his voice for us, the fishermen, so that we can be prosperous.”

K. B. Firaq is a rights activist in Gwadar, who has been researching the issues confronting the fishermen in Gwadar over the years. According to Firaq, fishermen have been living in Gwadar for centuries. In recent years, following the development in the port town, they have been displaced from their old settlements, including the town of Mullah Band,.

“As with the other issues confronting the people in Gwadar, Maulana has taken up their concerns to speak against injustices meted out to them [the fishermen], which is why they stand along with Maulana in the protests against the authorities,” he told me in his office in Gwadar.

The complaints are not just about Chinese activities: “Besides being displaced, their major issue is that of illegal trawling at the hands of Sindh-based giant trawlers involved in wiping out the fish stocks in the waters of Gwadar and elsewhere in Balochistan, while the provincial government is playing the role of a silent spectator.” But locals fear things will get even worse with the arrival of Chinese fishing boats: “After the arrival of Chinese trawlers, the local fishermen’s woes further compounded, as these Chinese trawlers are ten times more dangerous than the Sindh-based trawlers,” Maulana said.

The rise of a protest leader

“Before the arrival of Maulana on the scene, we were left in the lurch by our own local administration and government,” said Jan Bibi, an elderly woman hailing from the Mullah Band area of Gwadar, where the deep-water port is situated. “But Maulana came to help us raise our voice for our rights, including of the women, in the port town, which is why I joined him in the protests along with my children, even though I was injured in the recent protests by the police.”

Maulana began his initial protests in November 2021. For over 32 days, he and tens of thousands of people demonstrated on Marine Drive Road in Gwadar, which leads to the deep-water port area that is being developed by Chinese companies. He launched a second round of protests in late 2022, which continued for two months before a crackdown on December 26, 2022, in which reportedly over 100 supporters of Maulana were arrested.

Maulana and his supporters had blocked the junction connecting the Chinese-funded deep-water port and the Chinese-built Eastbay Expressway, which leads to the Makran Coastal Highway which connects Gwadar to Karachi, Pakistan’s most populous city, and the country’s major port.

Background interviews suggest that Maulana also threatened the Chinese workers at Gwadar, and demanded they leave the port town. In a picture that went viral on social media, Maulana and other locals displayed automatic rifles and other weapons.

But Maulana denied threatening Chinese workers in an interview with The China Project: “I displayed weapons because the provincial government had failed to establish its writ in the waters of Gwadar, where illegal trawlers have deprived us of the fish stock that our fishermen and the port town depend on.”

In Karachi, Chinese consul general Lǐ Bìjiàn 李碧建 said he had met Maulana and other senior party leaders of Jamaat-e-Islami in Karachi and Islamabad. “We were assured the protests are not against the CPEC in Gwadar,” Li told The China Project, adding that he was nonetheless concerned about the protests in Gwadar.

Why locals support Maulana

Professor Mumtaz Baloch teaches at the University of Balochistan in Quetta, the provincial capital of Balochistan. He told The China Project that he believes Maulana is addressing the issues of the people of Gwadar, which is why people follow him, in the hope of making their issues heard in the media and official circles.

“For a long time, there has been a political vacuum in Gwadar and elsewhere in Balochistan,” he argues, adding that Maulana has successfully filled this vacuum through his political charisma.

Masi Zainab, 65, is a leader of the women participating in the demonstrations. She goes door to door to bring women to the sit-ins and protests in Gwadar. The women have taken part in huge rallies in Gwadar in order to show solidarity with Maulana.

“When Maulana’s name emerged following the arrival of Chinese trawlers in Surbandan, we were protesting near the port area because the security personnel were not allowing our male fishermen from the sea,” she recalled while sitting at her tiny house in Mullah Band. “No one came to us except Maulana, that too he had heard my voice note on WhatsApp when he was going out of Gwadar.”

Since then, Masi Zainab said, he has been protesting for the rights of the people of Gwadar.

As of now, Maulana has been arrested following the crackdown on the protestors who had staged a sit-in at the junction connecting the port with the Eastbay Expressway.

Gwadar’s deputy police officer Najeebullah Pandrani told this reporter that he was arrested because “he was infringing on other people’s rights.”

“We accepted all of Maulana’s demands, but despite that he continued to protest,” said the deputy commissioner of Gwadar, Izzat Nazir Baloch.

“We will protest whenever Maulana gives the call,” said one of Maulana’s supporters in Gwadar, Naeem Baloch. “We are waiting for him to be released, but we’ll not go an inch back from the demands of our people.”

In the words of Nasir Rahim Sohrabi, a Gwadar based social activists, the issues of people in Gwadar are deep rooted, manifold, and complex, which is why locals support Maulana.

Last but not least, Maulana, undoubtedly, has a lot of local support, and people in the port town do not hesitate to stand up for their rights over Maulana’s single call. Therefore, it is high time for both Pakistani and Chinese authorities to pay heed to the people’s legitimate and constitutional demands in Gwadar, where Chinese has been heavily investing. Before being arrested, Maulana told The China Project, warning, “if Gwadar’s development is not meant for the locals, then they will continue to protest until or unless they are heard.”