China and Russia’s ‘journey of friendship’ continues as battle rages in Ukraine

Putin and Xi speak about mutually beneficial cooperation, but Beijing’s ties to Moscow fuel tension with the West.

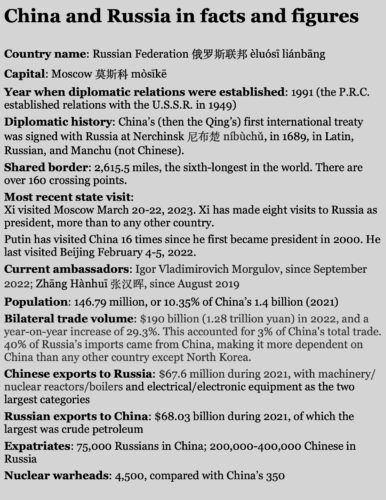

In the second installment of China’s World, our monthly series looking at China’s relationships with other countries, Duncan Bartlett focuses on the P.R.C.’s ties to Russia.

At the start of his three-day visit to Moscow that concluded yesterday, Chinese President Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 published an opinion piece for a Kremlin newspaper, which stated that “China and Russia adhere to the concept of eternal friendship and mutually beneficial cooperation.”

When Russian President Vladimir Putin met Xi, he admitted to being “slightly envious” of his esteemed visitor and spoke admiringly of the centrally managed Chinese economy.

This kind of mutual flattery suggests that Russia and China view themselves as solid partners, united in their challenge to the dominance of the established global order. China speaks of the countries as traveling on a “journey of friendship.”

They both envision a “multipolar world” in which their own actions are unconstrained by sanctions or retaliation. Yet there are issues that place the relationship between Russia and China under considerable strain. Chief among these is the war in Ukraine.

China will push for dialogue to end the war in Ukraine based on its 12-point plan

In public, China has not criticized the Russian invasion, nor has it voted to condemn Moscow at the United Nations. Chinese propaganda has stuck to the Kremlin’s line that the geopolitical security landscape in Europe has been ruined by the United States.

Nevertheless, Chinese companies have largely remained within the boundaries set by international sanctions, and the P.L.A. has avoided any overt support for the Russian military.

It may also be the case that Xi Jinping is more frustrated by the war than he cares to disclose. Last year, Putin acknowledged that Xi had come to him privately with “questions and concerns” relating to the Ukraine crisis.

Since then, China has been formulating what it calls “a political solution” to end the fighting. It takes the form of a 12-point position document, which has been praised for its “fairness” by Putin, who says it could serve as the basis for a resolution.

Success depends on whether Ukraine and the West are also willing to engage with China on the proposals. That seems unlikely — China’s proposal does not even acknowledge that what it calls the “conflict” is the result of a Russian invasion.

Xi Jinping is expected to outline his suggestions in a call to Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, although the timing has not yet been confirmed. Countries that back Ukraine militarily, including the United States, have already been scathing of the Chinese plan. The U.S. Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, said that calling for a cease-fire before Russia withdrew “would effectively be supporting the ratification of Russian conquest.”

And the Ukrainian Foreign Ministry spokesman, Oleg Nikolenko, said: “We expect Beijing to use its influence on Moscow to make it put an end to the aggressive war against our country.”

China is experiencing a range of adverse consequences as a result of the war in Ukraine

Katie Stallard, author of Dancing on Bones: How Past Wars Shape the Present in China, Russia, and North Korea, listed some of the negative consequences for China from the invasion of Ukraine in an article for the British newspaper The Sunday Times, which was published shortly before Xi’s visit to Moscow.

“Already, in just over a year, it has damaged China’s national interest in various ways,” she wrote, “by reinvigorating NATO, by undermining Beijing’s efforts to mend diplomatic ties with Europe, by weakening demand in crucial export markets, by galvanizing the rearmament of Japan, and by prompting the United States to rush weapons to Taiwan.”

There is a quid pro quo approach when it comes to the diplomatic relationship between Russia and China. In exchange for accepting that Russia was “provoked” into invading Ukraine, China expects Russia to comply with its principles on Taiwan.

These were boldly stated clearly by Xi Jinping at the National People’s Congress in March, when he said that external interference and separatist activities would be resolutely opposed. He vowed to unswervingly promote reunification of the motherland.

Russia used similar language during Xi’s visit to Moscow. It said it supports Beijing’s “one China” principle and acknowledges Taiwan to be an inalienable part of the P.R.C. The statement added: “Russia opposes Taiwan’s independence and supports Chinese actions to protect its sovereignty and territorial integrity.”

Since the Communist revolutions of the 20th century, China and Russia have regarded themselves as part of an international socialist brotherhood

A shared history forged by Communist revolution has shaped the China-Russia axis.

In his editorial for the Kremlin newspaper Rossiyskaya Gazeta, published on March 20, Xi Jinping wrote that Russia and China “are implementing the concept of friendship passed down from generation to generation, and traditional friendship is growing day by day.”

Putin’s framing of the war in Ukraine as part of a broader conflict with the West fits neatly with Xi Jinping’s ideology. In Moscow, Xi criticized geopolitical blocs that, in his view, are responsible for “damaging acts of hegemony, domination, and bullying.”

The Chinese leader wrote: “The international community is well aware that no country in the world is superior to all others. There is no universal model of government and there is no world order where the decisive word belongs to an individual country.”

Putin hoped that Xi’s visit to Moscow would show that Russia is not isolated and still has influential friends that share a similar worldview. Just one week ago, the Russian navy conducted joint exercises with both China and Iran.

“Putin is building his own bloc,” the journalist and Nobel Peace Prize winner Dimitry Muratov told the BBC. “He doesn’t trust the West anymore. He’s looking for allies and trying to make Russia part of a common fortress with China — as well as with India, Latin America, and Africa. Putin is building his own anti-Western world.”

The concept of “the West” also ropes in Japan, an ally of the United States.

Just as Xi Jinping was being given a red carpet welcome in Moscow, Japan’s prime minister, Fumio Kishida, made an unannounced visit to Kyiv, which included a joint press conference with Volodymyr Zelensky.

Kishida called the Russian invasion of Ukraine “an outrageous act that violates the international order.” He demanded that Russia immediately and unconditionally withdraw all its forces from Ukraine.

Kishida suggested that “Ukraine today could be East Asia tomorrow” — implying that the invasion could be a prelude to a Chinese attack on Taiwan. Using this rhetoric, Prime Minister Kishida has won political support for a sharp rise in Japan’s defense budget.

During his visit to Kyiv, Kishida emphasized that it is not just “the West” that condemns Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. He said that 140 countries voted to censure Russia at the United Nations General Assembly — including many nations in the so-called “Global South” — and this represents the majority of the international community,

China makes great efforts to win over leaders of Global South countries, such as President El-Sisi of Egypt and the Brazilian president, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, who is expected to arrive in China on March 28.

Russia is one of the only countries to have a trade surplus with China

Russia would like to deepen its economic relationship with China.

While the West weans itself off Russian energy, China is buying up oil and gas at reduced rates. More than 50% of China’s energy comes from Russia, and on March 22, the Kremlin announced that it will build a second gas pipeline, called The Power of Siberia 2.

This flow of oil and gas enables Russia to maintain a trade surplus with China, and provides Moscow with an economic lifeline in light of Western sanctions.

Nevertheless, Chinese imports are vital for Russia, ranging from smartphones to large manufacturing gear. China is an important source of goods that Russia finds difficult to obtain elsewhere, such as semiconductors.

In an effort to become less dependent on what they describe as “the hegemony of the U.S. dollar,” the two countries have also been trading in their local currencies. The yuan became an alternative settlement currency in Russia in 2022, when Moscow agreed to sell natural gas supplies to China, which would be paid for half in yuan and half in rubles.

In the joint statement at the end of their meeting in Moscow, Xi and Putin described China-Russia ties as “mature, stable, independent, and tenacious.”

“Russia needs a prosperous and stable China, and China needs a strong and successful Russia,” they said.

Yet in the eyes of most of the world, Russia looks far from strong or successful. It is continuing a fight with Ukraine, which is costing around 1,000 soldiers’ lives each day. Most of its international trading partners have abandoned it. And hundreds of thousands of Russian citizens have fled their homeland, with no intention of returning.