This is the story behind Taiwan’s Freedom of Expression Day, which falls today

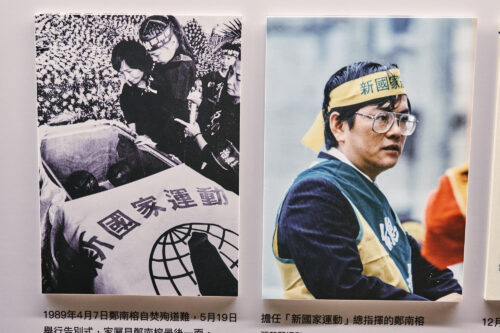

On April 7, 1989, pro-democracy activist Nylon Cheng a.k.a. Cheng Nan-jung self-immolated to protest anti-sedition laws that were used to silence dissent. A temporary exhibit in Taipei looks back on his sacrifice.

International tourists have flocked to Taiwan over the Qingming Festival holiday, and the first stop for many is Liberty Square, an important site in the country’s transition from authoritarianism to democracy. Looming over the expansive plaza is the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial, where the Republic of China pays homage to the man who enacted 38 years of martial law and imposed a Chinese identity on Taiwan – for a while, at least.

Chiang ((蔣周泰 Jiǎng Jièshí) sits at the top of the Chinese-style ziggurat modeled after the Altar of Heaven in Beijing, looking out over what was once his feared Taipei garrison, which enforced his White Terror on the capital. Within the monument’s base is a small museum featuring a permanent exhibit containing personal items owned by Chiang, including his two bulletproof Cadillacs.

A temporary exhibit space across from Chiang’s old wheels currently highlights the Taiwanese struggle for free speech: April 7 is Freedom of Expression Day. The exhibit is centered around Nylon Cheng (鄭南榕 Zēng Nánróng a.k.a. Nylon Deng a.k.a. Cheng Nan-jung ), the uncompromising Taiwanese publisher whose dramatic self-immolation in 1989 shocked Taiwan and shamed the Kuomintang party-state into relaxing its draconian sedition law. At the center of the exhibit is a statue of the charred corpse Cheng left behind. A documentary running on loop shows actual footage of his body on the scene, his hands curling inward and mouth frozen in an eternal scream.

A statue of Cheng Nan Jung’s burnt body on display as part of the exhibition, Taiwan’s Long Walk to Freedom of Speech, at the Chiang Kai Shek Memorial Hall. April 3rd, 2023. Photograph by An Rong Xu for The China Project

The day of Cheng’s death, April 7, has been a national holiday in Taiwan since 2017. It highlights both the free-speech hero’s sacrifice, as well as the fragility of freedom in a country whose hard-earned democracy is still young and is once again under threat from an uninvited Chinese ethno-nationalist government.

Beijing is not only attempting to curb discussion of Taiwan’s geopolitical status globally, it is applying its domestic laws to Taiwanese people commenting on the internet in Taiwan.

No one knows this better than Lee Ming-che (李明哲 Lǐ Míngzhé), who is perhaps the most famous example of the attempts by China’s Communist Party to chill speech in Taiwan. Lee, a community college administrator and human rights activist, was convicted of state subversion by a Chinese court in Hunan Province in 2017. His court appearance and forced confession took place 177 days after he had been disappeared by China’s authorities after entering the mainland from Macau.

Released last year after spending five years in a Chinese prison for a conviction based upon Facebook posts and other online comments he made while in Taiwan, Lee reflected on Cheng’s sacrifice.

“Nylon Cheng gave our generation of Taiwanese the total freedom of speech we have today,” Lee told The China Project. “As we enjoy this freedom, we need to ask ourselves: What price are we willing to pay today so that the next generation isn’t invaded by China, and can continue to have such freedom?”

Today Cheng’s office is the site of the Nylon Cheng Foundation, as well as a small museum that maintains the burned-out office that captivated Taiwan as it burned on live television, smoke billowing out from the outside as firefighters doused the flames. On April 6, the foundation unveiled a multilingual virtual tour of his former office, now the Nylon Cheng Memorial Museum, for people who can’t make the trip to northern Taipei.

A replica of Cheng Nan Jung’s burnt office as part of the exhibition, Taiwan’s Long Walk to Freedom of Speech, at the Chiang Kai Shek Memorial Hall. April 3rd, 2023. Photograph by An Rong Xu for The China Project

Speaking at the virtual museum’s launch on Thursday, Cheng’s widow — and former Taiwan vice-premier — Yeh Chu-lan (葉菊蘭 Yè Júlán) noted with a smile that “advancement of digital technology is enabling my husband’s story to pop up in living rooms and kitchens around the world.” She also thanked those in attendance “for remembering an incident from 34 years ago.”

A draft constitution for a Republic of Taiwan

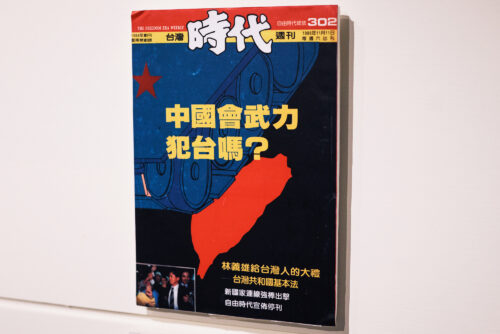

What precipitated that incident was Cheng’s magazine New Era Weekly publishing a draft constitution for a Republic of Taiwan. The government of Taiwan is still technically the Republic of China that Chiang relocated from China to Taiwan to avoid annihilation from Mao’s Communist revolution. The Republic of China (ROC, still Taiwan’s official name) may have democratized in the 1990s, but in 1989 it still had strict anti-sedition laws, which Cheng sought to challenge.

The last cover of Cheng Nan-jung’s magazine at the Cheng Nan-jung Liberty Museum in Taipei. April 4th, 2023. Photograph by An Rong Xu for The China Project

After publishing the draft constitution, Cheng was notified that a warrant had been issued for his arrest. He barricaded himself in his office off of Minquan East Road for more than two months, vowing that the Kuomintang would never take him alive. He was true to his word.

Will Nylon Chen’s death affect the next presidential election?

In a twist that highlights how young Taiwan’s democracy is: the officer who decided on April 7, 1989 to forcibly enter Cheng’s office is now a possible Kuomintang candidate for Taiwan’s next presidential election, only nine months away. Hou You-Yi (侯友宜 Hóu Yǒuyí), who is currently mayor of Taiwan’s largest city, New Taipei, has maintained that he was just doing his job and was not responsible for Cheng’s death. Cheng’s daughter, Cheng Chu-Mei (鄭竹梅 Zēng Zhúméi), is one of many voices who have criticized Hou for not apologizing for his role that day.

Today’s defenders of free speech and Taiwanese self-determination

Even though 1989 feels like a long time ago, the fight for freedom of expression, and self-determination in general, is still ongoing. Taiwanese voices have until recently been marginalized or sidelined by the very democracies that celebrate Taiwan’s achievements now that their relations with China have soured. Taiwan no longer being taboo in the West and elsewhere has opened up new opportunities for Taiwanese perspectives to reach a global audience.

Emily Y. Wu (吳怡慈 Wú Yící) is at the forefront of this trend. In 2019, Wu launched the podcast network Ghost Island Media, which has produced podcasts in English, French and Mandarin about emergent social issues in Taiwan.

“None of what we enjoy today and sometimes take for granted — the freedom, the democracy — none of this would’ve been possible if not for the activists of the past who paved the way for us,” Wu said. “We’re just continuing their work.”

Wu provided the narration for the virtual tour of Cheng’s former office. She said that it was a moving experience, despite already knowing the story.

“Reading aloud Nylon Cheng’s history, and his writing, to me it created a greater sense of urgency in terms of the work of our generation,” she said. “It’s not something we can do, or even what we should do; it’s something we must continue to do.”

Wu’er Kaixi (吾尔开希·多莱特 Wúěr Kāixī·duō láitè), a former Tiananmen student leader, has lived in Taiwan for more than two decades. He moved just months after Cheng’s sacrifice which had a major impact on Kaixi upon his arrival in Taipei. .

Now an emeritus board member at Reporters Without Borders’ Taipei office — its only Asia office — the former protester said he was immediately struck by Taiwan’s democratic transition when he arrived in 1990. When RSF was preparing to open its Taipei office, Wu’er Kaixi urged the organization to open on the anniversary of Cheng’s death, which it did in 2017.

“Taiwan transformed from a totalitarian state to the exemplary democracy it is today, and freedom of expression was fundamental to that transformation,” he said. “Nylon Cheng’s sacrifice was vital to Taiwan’s democratic transformation.”

Photos of Cheng Nan Jung on display at the exhibition Taiwan’s Long Walk to Freedom of Speech, at the Chiang Kai Shek Memorial Hall. April 3rd, 2023. Photograph by An Rong Xu for The China Project

Cheng’s advocacy for Taiwaneseness to be something based on values rather than blood has also resonated with Wu’er Kaixi and others. In 1989, whether one’s family had come over with the Kuomintang or arrived generations before was still a significant issue in Taiwan.

Cheng’s father was from China and his mother was Taiwanese. When Taiwanese revolted against and temporarily overthrew the KMT in 1947, two years after the ROC had seized the former Japanese colony, Taiwanese neighbors protected Cheng’s mother, who was pregnant with him, from Taiwanese engaged in revenge killings against mainlanders. In his writings, Cheng mentioned how heavily it weighed on him growing up to think that before he was born, his Taiwanese neighbors were protecting him.

For Wu’er Kaixi, who was born in China, carrying multiple identities doesn’t complicate his feelings for Taiwan.

“I have no problem carrying three identities,” he said. “I’m Uyghur by blood, Chinese by birth and Taiwanese by choice. If China one day attacks Taiwan, I know which side I’ll choose.”