ChatGPT and China: How to think about Large Language Models and the generative AI race

China’s tech companies face significant challenges in developing AI, including domestic censorship and regulation, and American export controls on hardware. But the U.S. approach might end up making the Chinese companies stronger.

Much ink has been spilled in the last few months talking about the implications of large language models (LLMs) for society, the coup scored by OpenAI in bringing out and popularizing ChatGPT, Chinese company and government reactions, and how China might shape up in terms of data, training, censorship, and use of high-end graphics processing units (GPUs) under exports controls from the U.S.

But what is really at stake here? The issue needs to be explored first outside the usual lens of great power competition. Here is a framework for thinking about this problem which you have likely not read about in all the many columns on the subject written by generalists, people with a clear China axe to grind, or investors plugging a particular technology. Then we can get to great power competition.

China’s approach to LLMs and ChatGPT-like platforms will be different

For China, the OpenAI phenomena is somewhat novel, as there are few equivalent organizations in China.

OpenAI is an artificial intelligence (AI) research laboratory consisting of the non-profit OpenAI Incorporated, and its for-profit subsidiary OpenAI Limited Partnership. Small and run like a startup, OpenAI has been able to move more nimbly than some of the major U.S. AI players, all of which have been working on similar services. But Google, AWS, and Meta all have other businesses and reputations to protect, and so have been more circumspect in rolling out new generations of generative AI applications. Not OpenAI.

In China, the rough equivalent of OpenAI is the Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence (BAAI). BAAI has developed Wu Dao, a GPT platform it claims is trained on 1.75 trillion parameters, and is able to simulate conversational speech, write poems, understand images, and even generate recipes.

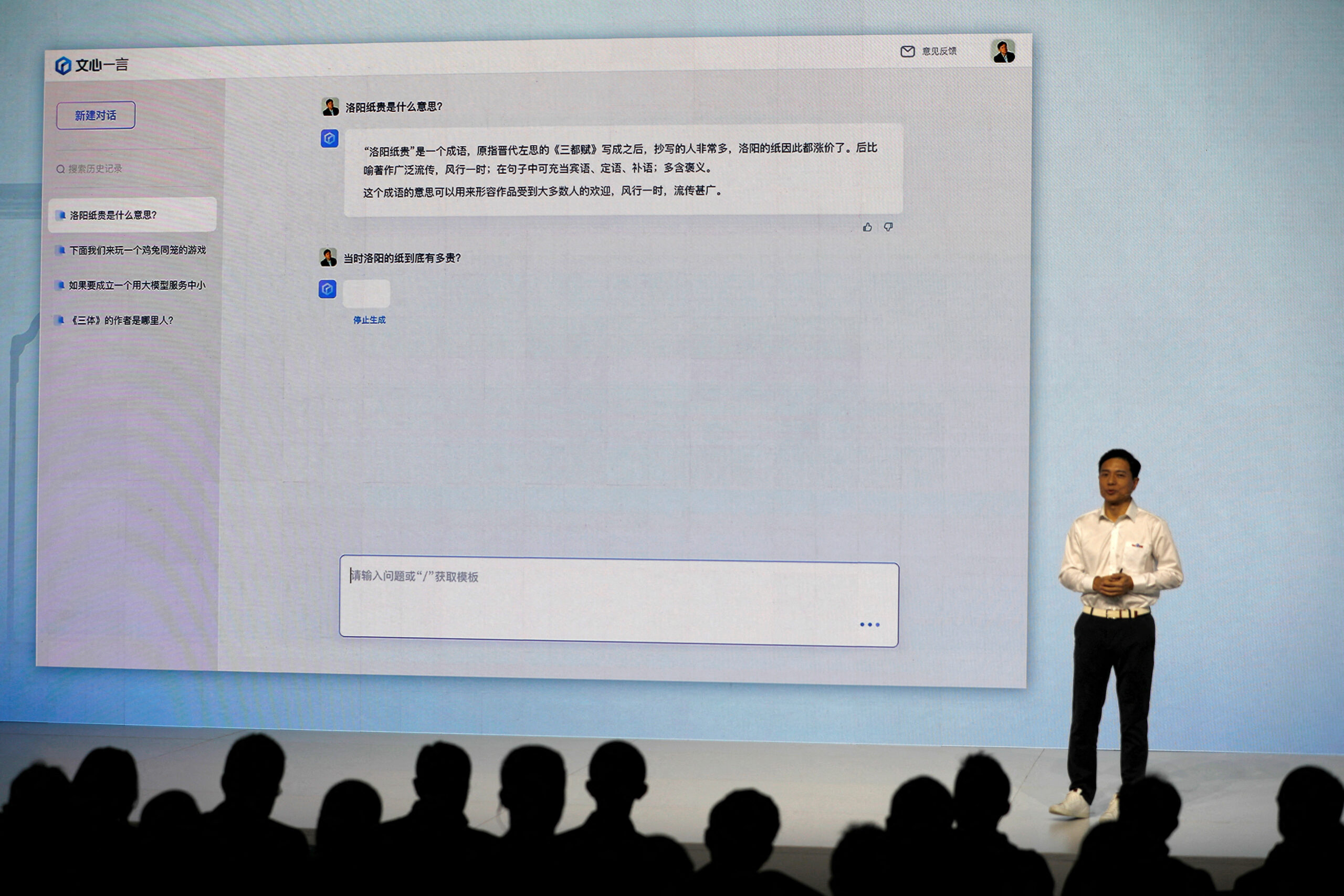

Last month a major conference was sponsored by a district government part of Beijing, there were pledges to support LLMs, and a growing number of Chinese companies including Baidu, Alibaba, and SenseTime have indicated that they are working on ChatGPT-like platforms for both general and domain-specific applications. Naturally, this type of buzz around generative AI has drawn the attention of regulators.

To emphasize the point that China’s approach to LLMs and generative AI will be different, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) this week came out with new draft rules for these platforms. The rules will seek to hold platform developers accountable for the legitimacy of the underlying data used to train algorithms, and responsible for “inappropriate content” generated by the platforms. In addition, users of the platforms will have to use real name registration and provide other information.

The new CAC rules build on a series of regulatory approaches to build a toolset to regulate AI, and pursue a different approach from the European Union or the U.S.. CAC’s move to create an algorithm registry — the Internet Information Service Algorithm Filing Systems — last year was perhaps the clearest indication that Chinese authorities were eager to get ahead of the game on regulation, even though their capacity to actually review the technical details of algorithms remains unclear. But the registry regulation was clearly a precursor for the current proposed rules around generative AI, as they mandated that recommendation algorithms with “public opinion characteristics” and “social mobilization capabilities” file with the registry. While the process of rolling out the registry has been vague at times, it appears to be intended to provide authorities with a way to track potentially problematic algorithms..

The “inappropriate information” issue is one at the heart of how different China’s LLM development and deployment will be. In general, state-of-the-art LLMs are typically “pre-trained” on huge amounts of data, which primarily means, as much openly available data on the internet as possible. This includes text and images, and even audio. Chinese LLM developers face a considerable challenge in ensuring that “content generated by generative artificial intelligence…embodies core socialist values and…does not contain any content that subverts state power, advocates the overthrow of the socialist system, incites splitting the country or undermines national unity.”

For Chinese firms, the decision on what data to use to train their models is much more complex than for their western counterparts. The magic of platforms like ChatGPT lies not only in the algorithms and training data, but in something called Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF). This is how the models can be trained to avoid sensitive topics, bias, and hate-filled language.

So Chinese models can be trained, for example, on uncensored data and then use RLHF to “align” the output with what Beijing is expecting for certain types of dialogues, i.e., avoiding sensitive political subjects that are typically censored on China’s internet, or any depictions and discussions of senior leaders like Xí Jìnpíng 习近平.

Here, the political content and image censorship problem is to some degree an extension of the broader alignment problem that is much discussed in AI circles today, around the issue AI safety. Alignment refers to the degree to which AI algorithms and applications should be designed to align with human values and interests, usually thought of as the intended goals and interests of the systems’ designers. As one of the core challenges of AI in general today, adding another highly sensitive problem of “political alignment” makes the issue more complex, particularly for Chinese companies now jumping on the ChatGPT bandwagon, such as Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, and many others.

Will regulation destroy the Chinese ChatGPT bandwagon?

The CAC rules come just as Chinese technology companies are all gearing up to release versions of ChatGPT. Already Baidu has released ERNIE BOT, and Alibaba this week announced that its ChatGPT-like service Tongyi Qianwen, will be integrated into the firm’s workplace collaboration app Dingtalk. AI giant SenseTime this week released several new AI-powered applications that included a chatbot and image generator. In February, Wáng Huìwén 王慧文, the co-founder of delivery giant Meituan announced a personal investment of $50 million to build a ChatGPT-like application, and Lightyear Technology, an AI company founded by the Wang, acquired Beijing OneFlow Technology, an AI architecture startup. There are now more than 20 Chinese firms with aspirations in this space, many more than in the US.

The challenges these companies face are substantial. They include:

1) Selecting data to train their algorithms;

2) Accessing advanced hardware for training in the cloud, given new U.S. export controls;

3) Avoiding running afoul of regulators over content and data issues.

U.S. competitors such as ChatGPT, Google’s Bard, and other LLM application platforms do not face similar constraints. All companies in this space face financial challenges in putting together clusters of advanced hardware chips and operating them over an extended period to train algorithms — this is not a game for the underfinanced without a clear business strategy and deep pocketed backers.

The political alignment problem

In the short-term, the political alignment problem will be most important. If development teams at major Chinese generative AI companies are expending significant efforts on high precision “political alignment,” this will detract from all the other pieces required to build a working and robust LLM and applications based on it, things like multimodality, tool use, agent problem solving, and so forth. While it is unclear as yet the extent to which CAC will hold companies accountable for lapses in content generation deemed “inappropriate”, at least in the initial phases of development, firms are likely to devote significant effort to getting the political alignment problem right.

It is possible that some teams could work on the political alignment problem by using a less complete data set to begin with, such as a set of censored data. That could be risky because the apps will eventually need to handle uncensored material during runtime with real users. For these models, some familiarity with uncensored data and dialogues is likely to be better for the alignment problem than never having seen uncensored data in the training phase. The outcomes could be unpredictable in ways that run afoul of CAC’s evolving regime around generative AI.

Chinese firms may have some advantages though. In terms of the types of benchmarks that are used to determine the quality of generative AI models, arguably the most important ones are now human-level benchmarks, such as standardized tests, bar exams, university entrance exams, and medical licensing exams — all of these have been used to benchmark ChapGPT. With traditional machine learning (ML) benchmarks being largely saturated now with the machine type scoring that exceeds human performance, the human level testing against ChatGPT-like models has become a new key benchmark. The Chinese educational system uses heavy levels of performance testing for both university and professional exams, and Chinese language models here are likely to have a significant advantage over western versions which may have less access to large Chinese language datasets and experience with Chinese language testing protocols. Baidu claims that in some benchmarks ERNIE 3.0 has outperformed state-of-the-art competitors on 54 Chinese natural language processing (NLP) tasks, for example.

The advanced hardware access problem

In the medium term, the advanced hardware access problem will start to creep in. The U.S. controls on advanced GPUs, for example, from the October 7, 2022 export control package, restrict China’s access to the most advanced GPUs from Nvidia, the A100 and H100. These advanced GPUs, and systems built with them, are ideal for training LLMs. ChatGPT, for example, is trained on 10,000 A100s.

The GPU to GPU data transfer rate, which is the key metric determining whether a GPU falls under U.S. export controls, is also important for training models. While Nvidia has come out quickly with versions of the A100 and H100 that cut the GPU to GPU data transfer rate to below the controlled level, Chinese companies looking to use this new hardware will still be at some disadvantage. This is likely manageable now, but will grow over time as Western competitors have access to cutting edge hardware and development systems.

Massive language models can be trained on a variety of hardware configurations. For example, Baidu has trained versions of ERNIE 3.0 and ERNIE 3.0 Titan on platforms such as its own clusters of Nvidia V100 GPUs, and a cluster of Huawei Neural Processing Units (NPUs) at Pengcheng Labs — Huawei launched the NPU line in 2019, calling its cutting edge version the “world’s most powerful AI chip”, and a competitor of the A100, before U.S. export controls prevented the firm from continuing to produce the chip at TSMC in Taiwan. Baidu is also offering its own NPU, with the latest version manufactured by TSMC. The next generation is expected to see commercial production in 2024. While these are touted as competitors to the A100, with the U.S. October 7, 2022 export control package, Chinese designers of GPUs and NPUs will almost certainly stop touting their products as Nvidia competitors, and play down or obfuscate specific performance parameters to avoid hitting the thresholds set in the U.S. controls.

The U.S. restrictions could also lead to greater innovation within Chinese companies using different hardware. For example, Chinese AI companies are already almost certainly exploring workarounds for dealing with less capable hardware, via software optimization methods and novel hardware configurations. Because advanced hardware is so critical for training LLMs, Chinese organizations will explore multiple ways to reduce training times and optimize training processes.

The U.S. restrictions are also incentivizing the more rapid development of domestic Chinese GPU alternatives for AI, with nearly a dozen companies involved in developing new hardware for both data center and edge applications. These include Biren, Moore Threads, Zhaoxin, Tianshu Zhixin, Innosilicon, and Xiangdixian. The major constraining factors for developing a competitive GPU, particularly for AI applications, are the cost of a new hardware design and creating alternative development environments to rival Nvidia’s widely used CUDA system.

Ethics, safety, and governance

Finally, over the long-term there is the broader problem of how China aligns with the rest of the world around AI ethics and safety, and governance issues. What does the particular issue of generative AI mean for the geopolitics of AI in general, and the geopolitics of generative AI models in particular?

The idea that the U.S. and China are competing in AI has driven a narrative about an “AI arms race,” to which hype about ChapGPT has added. When thousands of AI researchers and AI ethics researchers organized by the Future of Life Institute in late March signed a letter that called for a pause in generative AI development, many observers noted that China was unlikely to go along with such a pause. Many AI veterans acknowledged that there was no realistic way to implement a moratorium, but still warned that if the U.S. hit the pause button, this would allow China to gain an advantage. Also this week, not to be outdone, the Commerce Department issued a call for comments on how companies should think about “AI accountability,” to inform policies to support AI audits, risk and safety assessments, certifications, and other tools that can create earned trust in AI systems.

It appears that domestic forces on both sides of the Pacific are driving a greater bifurcation of how the U.S. and China both develop and regulate AI. Beijing has chosen a much more proactive approach to regulation, which differs from both the European Union’s approach via the EU AI Act, and the U.S. approach, which currently lacks a comprehensive legislative or regulatory agenda. As I argued in a 2021 paper on the geopolitics of the metaverse: “for the metaverse, the widening divide in terms of ‘values’ between the U.S. and China and other authoritarian countries has already significantly bled over into cyberspace. The decoupling of data flows, applications, and deeper layers of the technology stack has already been happening for some time, and is likely to continue, catching metaverses in its wake.” Clearly generative AI is also going to get caught in the bifurcation process, as regulatory regimes diverge, along with likely hardware and software development environments.

Generative AI models and applications are likely to diverge more quickly and decisively than some other parts of the information technology stack, particularly given the problems of political alignment, different regulatory pressures, and hardware and software development. Because LLMs require a large amount of computing power, and advantages in their development will accrue to large and well-funded technology companies with the financial and human capital required to develop and maintain applications, it is possible that more Chinese companies will jump into the fray, despite all the challenges. China is awash in AI software development talent, and U.S. efforts to control advanced hardware are only likely to be viewed as a challenge to be overcome.

In focusing on controlling access to AI-related hardware as part of U.S. efforts to maintain dominance of advanced computing capabilities, the U.S. may have ensured that Chinese companies will dominate the generative AI space in the future both within China and in developing countries that will favor Beijing’s approach.