When Comrade Xi invited Monsieur Macron to tea

Xi Jinping took visiting French president Emmanuel Macron for a pas de deux in the Pines in a garden originally built for Chairman Mao. Macron was suitably impressed, and said all the right things that a ‘true friend of China’ must say.

It’s 45 years since I first heard about South Lake, the guesthouse where Xi Jinping served up tea and history lessons to French President Emmanuel Macron on 7 April this year. It’s over half a century since I swam at Beidaihe, the Party’s seaside resort; over forty years since I enjoyed a gift of freshly picked fruit from Marshal Ye Jianying’s orchid at Jade Hill outside Beijing; forty years since I was investigated by the Communist Party’s Central Office for having slipped into Mao’s former residence in the Sea Palaces (Zhongnanhai) in the heart of Beijing; nearly twenty years since I hung out at his rambling residence on Lushan in Jiangxi; and, fifteen years since I was able to spend time at Liu Zhuang, the Chairman’s favorite lakeside retreat in Hangzhou and the place that he called his real home.

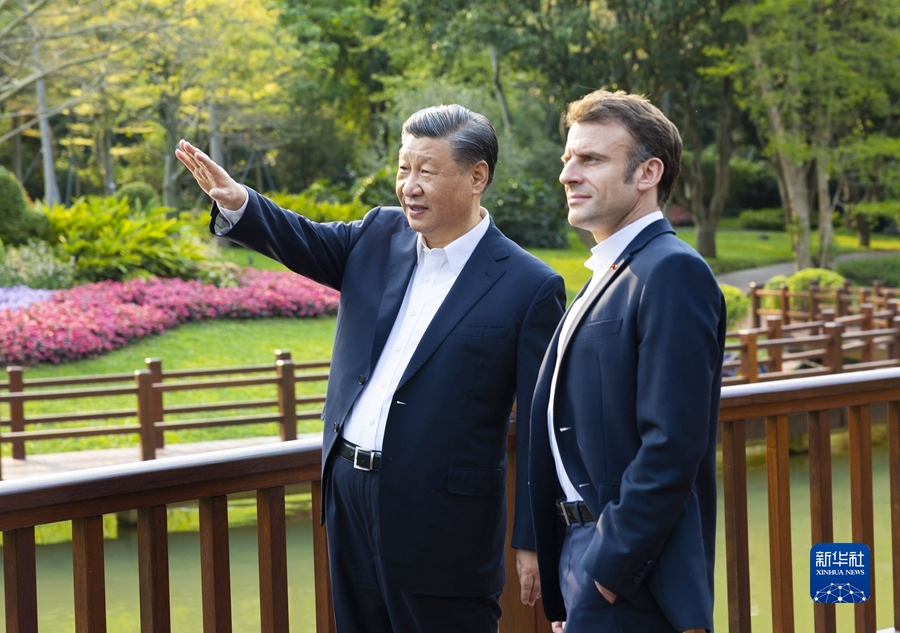

A Pas de Deux in the Pines. Source: Xinhua.

In the Garden of Pines

Spring in Guangzhou: the brilliance of the season is heightened by a brocade-like covering of blossoms. The Garden of Pines, nestled in the foothills of the White Cloud Mountains, is embraced by lakes, its pavilions and lookouts enlivened by bubbling cascades. The scenery is suffused with poetry…

So reads the preamble to the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs report on the perambulation of presidents Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 and Emmanuel Macron around the Garden of Pines resort outside Guangzhou on April 7, the last day of the French leader’s controversial trip to China.

As they strolled through the gardens the two heads of state engaged in casual conversation, stopping at times to appreciate a picturesque landscape that exemplifies the unique geography and climate of southern China.

Written in the mawkish style of party-state prose deployed when describing politics as romance, in an updated version of what Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 dubbed “revolutionary romanticism married to revolutionary realism,” the Foreign Ministry’s report fused formulaic poetic turns of phrase with carefully sculpted diplomatic fact. Since Mao first championed the concept in 1939, politics suffused with poetics has been a central feature of what I think of as the Communist Party’s “mytho-poetic hyperbolic complex.”

Having taken seats by the lake, the two leaders pursued a discussion that ranged over history while engaging with the present. They sipped fine tea as they appreciated the scenery.

The banality of the Foreign Ministry’s report reminded of an earlier moment in Sino-French history — the meeting of French president Georges Pompidou and Mao Zedong in September 1973. That encounter featured in Peking Duck Soup, a documentary that lampooned Chinese politics while taking side-swipes at France’s engagement with the People’s Republic — Charles de Gaulle’s government had fully recognized the P.R.C. in 1964, becoming the second Western power after the U.K. to do so. In his 1977 review of Peking Duck Soup, the sinologist Simon Leys observed of the Mao-Pompidou meeting:

…while the screen shows us the two leaders putting their great jovial heads together for a talk, the soundtrack plays the tune of Jingle Bells barked by a clever collection of singing dogs. This vocal rendition by trained poodles, so mercifully drowning out the words of the two statesmen — if you remember, their actual exchange, conducted with the sententious wisdom of a pair of traveling salesmen in ladies’ underwear, concerned the historical evidence (and some conjectures) on Napoleon’s stomach troubles — barely has time to ruffle the delicate good taste of all sensitive members of the audience when the real act of indecency occurs.

Half a century later, Xi Jinping’s high tea for Emmanuel Macron disguised another act of indecency — Macron’s fawning acceptance of “Chinese wisdom” as promoted by the Chairman of Everything. That having been said, however, some relatively routine “foreign handling” might have been a welcome break for Xi Jinping who, after years of byzantine political maneuvering, was now arguably the most powerful Chinese leader, be it in terms of his accumulated titles or in actual political strength, since the First Emperor of the Qin 2,200 years ago.

After all, as Xi told his French guest: “To understand China today, you have to start with Chinese history.”

Macron remarked on the “very fragrant tea” and sat seemingly entranced as Xi launched into a boilerplate recitation of select historical data points: Guangzhou was the cradle of the revolution that brought down China’s last imperial dynasty in 1911 as well as being at the vanguard of the nation’s economic reforms. Today, Xi emphasized, Guangdong province “continues to play its role as a bellwether and a locomotive for high-quality development.”

The venue for the latest jovial exchange between the leaders of China and France — the Garden of Pines (松园 sōng yuán) to the north of Guangzhou, also happens to be where Xí Zhòngxūn 习仲勋, Xi Jinping’s father, had started his tenure as leader of the province in 1978. As the New York Times reported:

President Xi Jinping recalled “taking notes in order to understand” when he visited his father, then governor of the southeastern Guangdong province, in 1978. He also observed, extolling Chinese economic development, that the province now has “four cities with more than 10 million people.”

It was an exchange of remarkable intimacy, the two leaders, tieless, sharing pleasantries in what was once the official residence of Mr. Xi’s father.

Tea after a stroll. Source: Xinhua.

China’s Secret Gardens

When I first heard about the Garden of Pines in 1978, it was known by the shorthand “South Lake” (南湖 nán hú). A heavily guarded Party compound shrouded in secrecy, the villas dotted around the lake were rumored to have been built for Marshal Lín Biāo林彪, Mao’s “hand picked successor” who died in mysterious circumstances following a coup attempt in September 1971. Locals believed that a submerged command center under South Lake was to have been Lin Biao’s headquarters in the event that the coup failed. From there, he would lead a military resistance in south China against Mao (codenamed “The B-52” in Lin’s plot) in the north.

In reality, Guesthouse Number Six of the Guangdong Revolutionary Committee, as South Lake was formally known, had been built for Mao and his supporters in the early 1970s. Although Mao never visited, the compound boasted a status equal with the other villas and garden-retreats built specifically for Mao in Shanghai, Hangzhou, and Wuhan — where the Chairman spent most of his time. In 1980, Guesthouse Number Six was renamed South Lake Hotel. Only in 1982 did it become the Garden of Pines.

Garden palaces were also favored by many Qing dynasty rulers. They directed the affairs of state from secluded demesnes and they also entertained foreign visitors in carefully choreographed “guest rituals” aimed at wooing and overwhelming local allies and outsiders alike. In 1793, for example, the Qianlong emperor met with the British Lord Macartney first at his Hunting Lodge in Chengde and again at the Garden of Perfect Brightness just outside Beijing. The Empress Dowager, de facto ruler of the empire during its last decades, courted diplomats’ wives at the summer palace refurbished to celebrate her sixtieth birthday. During the Republic of China, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek (Jiǎng Jièshí 蔣介石) used his villa at the Guling hill station at Lushan, Jiangxi province — known as his “Summer Capital” — to meet with American diplomats who he was anxious to keep on side, as well as with representatives of the Communist Party with whom he tussled.

Despite these dynastic and republican precedents, the model for the networks of villas, guesthouses and hotels where China’s post-1949 Communist leaders could both be entertained and foreign dignitaries showered with socialist hospitality was the “Reception Office,” or Jiāojìchù 交际处.

After establishing a base at Yan’an in northern Shaanxi, west China, at the end of the Long March in 1935, the Communists established a network of courtesy stations, or reception offices, in Shanxi, Sichuan, Guangdong, and Guangxi to host central party leaders, targets of the united front work as well as influential “foreign friends.” When the Chinese Soviet Republic was renamed the “Shaan-Gan-Ning Border Government” in 1937 its main entertainment venue was known as the Yan’an Reception Office. It boasted accommodation, a dance hall, a conference hall as well as the Victory Canteen (胜利食堂 shènglì shítáng), which served both Chinese and Western food.

Following the Communist victory in 1949, People’s Government Reception Offices were established in cities and provinces throughout the country. Generally housed in confiscated mansions and in the best hotels, the reception offices were primarily used to host cadres from Beijing of vice-ministerial rank or above, as well as deputy provincial leaders or above. They were also for the use of National People’s Consultative Congress, leaders of the defunct democratic parties of the rank of vice-chairman upwards, as well as élite “democratic personages” along with senior representatives of ethnic minorities and religious groups. The reception offices did double duty when Beijing hosted and entertained visitors from the Soviet Union and other fraternal socialist countries.

From the 1980s, the old reception offices were reformed. Many of the once-exclusive venues also became commercial enterprises. Party leaders also built new villas boasting top-line appurtenances to match, or even outdo, the excesses of global elites. During the high-tide of condoned corruption in the early Noughts, private clubs and villas also proliferated. Xi Jinping’s targeted purge of malfeasants has seen the Party requisition some of properties and repurpose them for the exclusive use of newly favored members of the nomenklatura — it isn’t corruption when the Party condones your access to luxury on the basis of “the burdensome requirements of work” (工作需要 gōngzuò xūyào). A well-known example is “The General’s Mansion,” the lavish Beijing residence of Xú Cáihòu 徐才厚, the vice-chairman of the Central Military Commission who was purged in 2014.

Music that only a true friend can understand. Source: Xinhua.

Tuning in, turning on

After delivering his potted lecture on Chinese history and an explanation of “Chinese-style Modernization” — a newly fashionable concept that has actually been at the heart of China’s transformation from the late-Qing dynasty — Xi Jinping encouraged Macron and the French businessmen in his party to “continue their enthusiastic engagement with the trade fairs in Guangzhou and Shanghai.”

Macron’s reply, according to the official Chinese report, was:

True friendship means mutual understanding and mutual respect. France appreciates China’s consistent support for France and Europe in maintaining autonomy and unity, and is ready to work with China to respect each other’s core interests including sovereignty and territorial integrity, open markets to each other, and strengthen technological and industrial cooperation, as well as cooperation in artificial intelligence and other technologies, to help each other achieve development and prosperity.

Pompidou would have been proud.

Having finished their tea, the two leaders “followed the strains of a melody into the Hall of White Clouds where a lone musician was playing ‘Lofty Mountains, Flowing Streams’.” Xi told his guest that it was “a thousand-year-old melody being played on a thousand-year old qin” 千年古琴奏千年绝唱. It was an inspired work by the ancient musician Bó Yá 伯牙. As the official report noted: “the two presidents had savored traditional Chinese tea and chatted about the rise and fall of powers over the past thousand years” 品千年茶韵论千年兴替. Now, Macron called for pen and paper so he could note down the name of the tune he had just heard.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

Xi related the story of Bó Yá (incorrectly referring to the ancient musician as “Yú Bóyá” 俞伯牙 — a common mistake) and Zhōng Zǐqī 钟子期, recorded in Lièzǐ 列子, a fourth-century CE Daoist text

Bo Ya was a good lute-player, and Zhong Ziqi was a good listener. When Bo Ya strummed his lute, with his mind on climbing high mountains, Zhong Ziqi said:

“Good! Lofty, like Mount Tai!”

When his mind was on flowing waters, Zhong Ziqi said:

“Good! Boundless, like the Yellow River and the Yangtze!”

Whatever came into Bo Ya’s thoughts, Zhong Ziqi always grasped it.

When Zhong Ziqi died Bo Ya is said to have “broken his qin and severed its strings” (破琴绝弦 pò qín jué xián) since there was no one who could really “appreciate his tunes” (zhī yīn 知音). Over time, the term zhī yīn came to mean a deep mutual understanding and appreciation.

Xi Jinping offered a short version of the famous anecdote (video) before telling Macron that “Only a heartfelt friend can truly understand this tune” (只有知音能听得懂这个曲 zhǐ yǒu zhīyīn néng tīng dé dǒng zhège qū). The widely used and hallowed term “zhī yīn” was thus press-ganged into the service of China’s “friendship politics.”

Having chimed the well-worn Chinese line about “friendship” — a “trigger word” in the China’s IR lexicon that means “you agree with me on all substantive points” — over tea, Macron had demonstrated that he was on the “right wavelength” with his host.

In one his most famous, and oft-quoted, writings Mao Zedong observed:

The first and foremost question of the revolution is: who is our friend and who is our foe?

谁是我们的敌人? 谁是我们的朋友? 这个问题是革命的首要问题。

Shéi shì wǒmen de dírén? Shéi shì wǒmen de péngyǒu? Zhège wèntí shì gémìng de shǒuyào wèntí.

The answer to Mao’s question has underpinned official attitudes to outsiders since 1949 and “friendship” (友谊 yǒuyì) was and remains the unmovable cornerstone of Chinese diplomacy and Sino-foreign exchange.

Like Macron, over the decades other foreign leaders, not to mention diplomats, business people, academics and sundry others, have been similarly ensnared in the net of being a “friend” (朋友 péngyou ) of China, or, worse still, “a special friend”. To be a friend of China, the Chinese people, the party-state or, in the reform period — even a mainland business partner, the foreigner is expected to stomach unpalatable situations, as well as to keep silent in the face of egregious behavior. A “friend of China,” or an “old Friend” (中国的老朋友 zhōngguó de lǎo péngyǒu) might enjoy the privilege of offering the occasional word of caution in private; in the public arena, however, he or she is expected to have the strategic nous, good sense and courtesy to be “objective” (客观 kèguān), that is, to toe the line or parrot official Chinese talking points.

Macron proved himself more than willing to comply with China’s friendship politics and think of himself as what Xi Jiping called a zhī yīn 知音 — someone who chimed. During a lavish private banquet at the Garden of Pines Macron declared that his “friendly and in-depth exchanges [with Xi] over the two days had enabled him to appreciate China’s long history and splendid culture, and have a better understanding of the concepts of modern Chinese governance.”

Barbarian Management

The carefully choreographed performance at the Garden of Pines was only the latest in a series of other grandiose but low key diplomatic feints of a kind favored by Xi Jinping: There was the banquet that Xi hosted for U.S. President Barack Obama at Yingtai in the party-state compound of Zhongnanhai in November 2014, after which the leaders strolled around the ornate island that was once the prison of Guangxu Emperor. It is known as “Evening Chats on Yingtai” (瀛台夜话 yíngtái yèhuà). Donald Trump’s visit to the Chinese capital in November 2017, when Xi and Péng Lìyuàn 彭丽媛, China’s first lady, gave the U.S. president and Melania Trump a short tour of the Forbidden City, followed by tea and a truncated Peking opera performance, is referred to as “Meeting Over Tea in the Palace Museum” (故宫茶叙 gùgōng cháxù). And, after Xi entertained visiting Indian Prime Minister Mahendra Modi at the East Lake Guest House in Wuhan in April 2018, it was dubbed “The Spring Outing on East Lake” (春游东湖 chūn yóu dōng hú).

Perhaps the Xi-Macron confab in Guangzhou will be known as “Pas de Deux in the Pines” (松园双人舞 sōng yuán shuāngrén wǔ).

When Beijing started negotiating with the outside world in the 1840s, the traditional language of “barbarian management” was employed. Some of the old vocabulary seems relevant again today. The old tactics combined “softening up by means of a ritualistic embrace” (怀柔 huái róu), “coddling with the aim of pacifying” (抚驭 fǔ yù), and “tethering” (羁縻 jī mí) with the aim of “manipulating the clashing interests among barbarians to manage the barbarians” (以夷制夷 yǐ yí zhì yí). The terms are dated, but the strategic reasoning behind them is familiar.

However, for all of the planning and thought put into them, Xi Jinping’s staged lyricism has generally yielded few practical results. As the old Buddhist saying puts it: “flowers may shed their petals on purpose, but they’re thoughtlessly swept away by the flowing river” (落花有意,流水无情, luò huā yǒu yì, liú shuǐ wú qíng). After the banquet at Yingtai, once back in Washington, Barack Obama continued to pursue the U.S. pivot to Asia and the Trans-pacific Partnership agreement. Regardless of that cultural grooming at the Forbidden City, America’s increasing alienation from Beijing continued apace under Donald Trump. And boating on Wuhan’s East Lake had scant impact on India’s Modi and did nothing to ameliorate Sino-Indian border disputes.

Emmanuel Macron, Xi Jinping’s new BFF, might have indulged Gallic bravura on his flight back home, but talk of a French-led third pole in global affairs is about as meaningful as Charles de Gaulle’s celebrated observation that “China is a big country inhabited by many Chinese.”