TikTok is the focus of U.S. lawmakers, but Chinese spies get more out of LinkedIn

China’s 2013 hack of U.S. government personnel records exposed American LinkedIn users with security clearance to recruitment and blackmail. But how much does the U.S. really have to worry about Chinese spies anyway?

A major social media platform is known to have been used by Chinese spies to target government officials in the United States and elsewhere, luring them to betray their countries, yet few people in Washington are talking about it.

It is not TikTok.

From 1987 to 2012, Kevin Mallory worked in a variety of intelligence jobs, including as a Central Intelligence Agency case officer recruiting spies. In February, 2017, Mallory found himself out of work, behind on his mortgage and $200,000 in debt when he received a message on LinkedIn from one Richard Yang, inviting him to become a part of his network.

Mallory’s training led him to suspect that Yang was likely a Chinese spy, and court records show that Mallory replied, “I’m open to whatever. I’ve got to — you know — pay the bills.”

Richard Yang then passed Mallory to Michael Yang, likely a member of the Shanghai bureau of the Ministry of State Security (MSS, 国安部 guó’ān bù), China’s main civilian intelligence agency. (Their Chinese names could not be confirmed.)

The Yangs told Mallory they were looking for an expert on foreign affairs to help them with research for the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences. The “research” they asked him for turned out to be classified information. Although the U.S. is unsure how much spying Mallory did for the MSS, in 2019, he was sentenced by the Virginia Eastern District Court to two decades behind bars, a term he is now serving at the U.S. Penitentiary in Canaan, PA.

In 2018, William Evanina, then America’s top spycatcher, said China was running a “super aggressive” effort on LinkedIn to recruit spies. Evanina, then the director of the U.S. Counterintelligence and Security Center, told Reuters that LinkedIn’s website was the “ultimate playground for collection” of intelligence because government officials frequently post about their security clearance status, making it easy for Beijing’s spooks to spot targets.

At the time of the Mallory case, LinkedIn Vice President of Trust and Safety Paul Rockwell said that the company was talking with U.S. law enforcement and doing “everything we can to identify and stop this activity.”

The U.S. is not the only nation being targeted on LinkedIn. A French report claimed that Chinese spooks approached 4,000 members of the French government and business elite on LinkedIn. German security services concluded that at least 10,000 German citizens were contacted by Chinese spies on the social network, warning the number was probably a significant undercount. In 2021, the British government warned that spies had tried to contact more than 10,000 U.K. nationals to lure them to spy. This last report did not point the finger at China, but the recruitment efforts sounded similar to those in the U.S., France, and Germany.

LinkedIn declined to comment for this article.

America’s spring season of paranoia

In the spring of 2023, Chinese spying is having a moment thanks to a series of events that have further exposed American fears about the rising power across the Pacific.

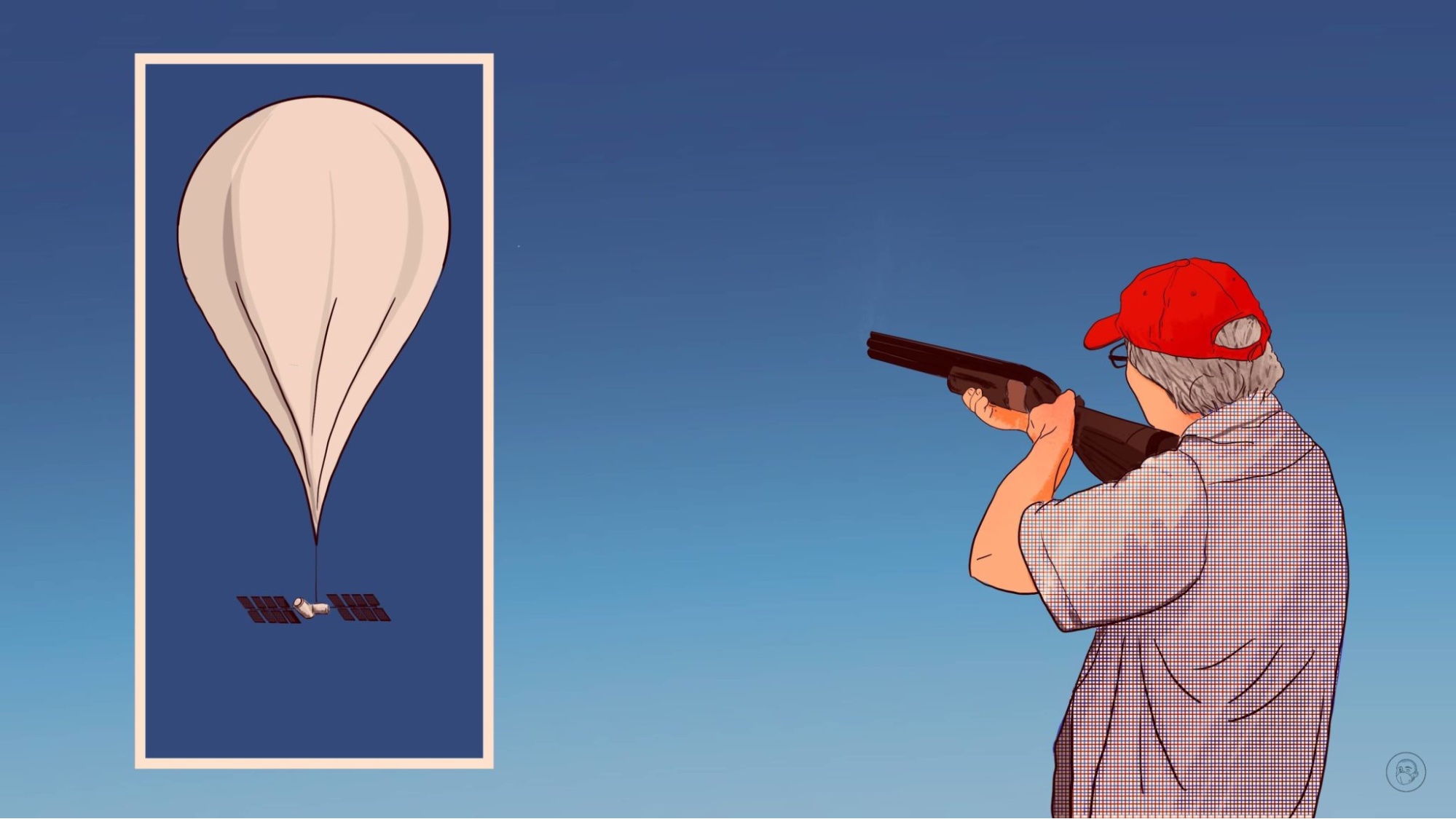

In March, the world tracked a Chinese spy balloon floating across the width of the U.S. and watched as a bipartisan committee in Congress grilled TikTok’s CEO about the ways the Chinese social media platform famous for teenage dance videos might be threatening American Democracy.

Then, in April, a national security leak by a young Massachusetts Air National Guardsman touched on China, amplifying fear of Chinese spying and once again making Beijing into a political football for U.S. policymakers heading into an election season. Also in April, New York lawmakers exposed that Chinese police had set up an office in Manhattan’s Chinatown from which they ran intimidation campaigns against ethnic Chinese who hold views divergent from those of the Chinese Communist Party. On April 26, Charles Lieber, the former Harvard chemist, was sentenced by a court in Boston for lying about his ties to China in a case of economic espionage.

As the U.S. Republican and Democratic parties jockey for position as inflation soars and Russia wages war in Ukraine, Chinese infiltration of the U.S. completed the American fear sandwich best described in a comment by Florida Republican Congressman Mario Diaz-Balart, who called TikTok “A Chinese Communist Party balloon in everybody’s home.”

Lawmakers across the country in another red state, Montana — where the Chinese spy balloon was first spotted in U.S. airspace — quickly became the first to approve a full ban of TikTok.

Yang Zeyi, a journalist at MIT Technology Review who works on issues related to Chinese tech, wonders about America’s reaction to TikTok in the current political climate.

“Nationalism is a part of it,” said Yang, who grew up in Wuhan before studying at Columbia University in New York.

“Tiktok is not significantly different from other social media apps, according to experts. It is under attack because it is a Chinese company, probably. They have privacy protection issues, but these are the same that that all social media have.”

Full of Hot Air

American politicians and the spooks meant to guard them, and all U.S. citizens, warn that TikTok is a spy threat, but offer little evidence to back their claim.

Researchers at the Citizen Lab, an independent outfit that studies internet openness and security at the University of Toronto, did an analysis of TikTok and Douyin, a sister app for China’s intranet. Their 2021 study found no evidence that the apps, both created by Beijing-based parent company ByteDance, collected contact lists, recorded photos, videos, or audio, or sent geolocation data to anybody (let alone the Chinese Communist Party) without user permission.

If espionage in social media is such a threat, why are U.S. politicians not also clamoring to ban LinkedIn, where, unlike on TikTok, there appears to be ample evidence of Chinese agents fishing for classified information?

“The potential for economic espionage is bigger for LinkedIn,” said Robert D. Atkinson, president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, a Washington, D.C. think tank. “It is a way to connect with business people, people involved with technology. TikTok is not.”

When The China Project asked if the average American should be worried about TikTok, Bruce Schneier, Harvard expert on cybersecurity, emphasized that TikTok was not all that different from American internet companies.

“Nah, Facebook and Google are probably worse. We built an internet with surveillance at its core. That is what the internet does. We cannot just say, ‘They can’t do that.’ Everybody spies.”

Sure. Spies are gonna spy, but cooler heads say the U.S. has less reason to fear than the current Balloongate-TikTok bomb threat suggests.

The MSS and other Chinese spy agencies are collecting vast amounts of secret data, but their spies are sloppy. With good counterintelligence the China threat can be managed.

China’s spies are Keystone Cops

Ed Peng (彭雪華 Péng Xuěhuá) was typical of the threat posed. He was an ethnic Chinese who was very bad at spying.

In March 2015, Peng, a naturalized U.S. citizen, began working for the MSS as a cut-out, spy jargon for a go-between who carries money and messages between an intelligence officer and his or her asset. For four years, Peng’s spying typically involved him booking a hotel room in the San Francisco Bay Area or Columbus, GA, leaving $20,000 in a drawer in the room, then disappearing after having asked the desk to let a friend into the room. When Peng returned, the friend had come and gone, taking the $20,000 and leaving a secure digital memory card full of what Peng thought were U.S. military secrets. Peng would then jet off to China, taking the SD card to his MSS handlers.

What neither Peng nor intelligence officers at the MSS realized was that, for four years, they were being fooled by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, whose agents had sent Peng the “friend,” who was really a double agent, slipping Peng and his MSS contacts what intelligence specialists call chicken feed, worthless secrets they are willing to give away to fool their mark into returning for more.

Peng also never noticed that he was being followed by the FBI, whose agents filmed him in each of his hotel rooms. Peng didn’t practice even basic tradecraft, the sneaky techniques of intelligence gathering and evasion that spies use to make sure that they are not caught spying. More surprising was that MSS officers reading through the SD cards never realized that they were being strung along by the FBI. In the realm of human intelligence, or humint, China’s spies are more Keystone Cops than Jason Bournes.

“MSS officers used to not be very well regarded by intelligence officials in other countries, including the U.S., France, Britain and Canada,” James Olson, a former CIA officer said. “We’ve not seen overly sophisticated tradecraft from Chinese spies,” Olson said, adding the caution that their skills may be improving and he still considers China “the greatest counter espionage threat” in the world.

In his book, Chinese Espionage: Strategies and Tactics, Nicholas Eftimiades, another ex-CIA officer, collected 595 cases of known Chinese espionage. In his database, Eftimiades found that 80 percent of those caught spying for China are ethnically Chinese and 90 percent are men. Many of the cases he looked at were carried out by low-level operatives like Peng. Two-hundred-eighteen, or 37%, showed no tradecraft. Of the 96 cases involving MSS officers — China’s top spies — 25% were caught showing no use of tradecraft, and another 14% used only limited tradecraft, a fact Eftimiades called “astounding.”

By comparison, “the tradecraft of [Russian] KGB, [East German] Stasi and CIA officers was generally good,” Paul Maddrell, editor of The Image of the Enemy: Intelligence Analysis of Adversaries Since 1945, told The China Project. “I know of no case when they showed little or no tradecraft.”

Another case of a bumbling Chinese spook with little training is Christine Fang, who posed as a college student but actually was sent to California by the MSS to spy on politicians. When Fang met out in the open with her handler, an MSS officer working undercover in the Chinese Consulate in San Francisco, it was easy for the FBI to surveil the pair.

“Her controller did not seem to realize that the FBI would be all over him if he was meeting with her in public,” said Matthew Brazil, co-author of Chinese Communist Espionage: An Intelligence Primer. “That is definitely a training problem.” Other spies working for China — Candance Marie Claiborne, Ron Rockwell Hansen, and Jerry Chun Shing Lee (李振成 Lǐ Zhènchéng)— all showed signs of slapdash tradecraft.

The MSS appears to be aware of this training problem. It does not send its ranking spies into the U.S. unless they have diplomatic immunity. So, while Fang’s handler was protected, she, as a low-level recruit, was not. She was expendable, but also a liability to the MSS.

Evidence of China’s intelligence higher-ups’ willingness to sacrifice operatives better trained than Fang is seen in the case of Chi Mak (麥大志 Dài Dàzhì), one of the most productive Chinese intelligence officers ever caught in the U.S, a man who helped the P.R.C. steal the designs of NASA’s Space Shuttle, a crime for which the recruit he ran, Dongfan Chung (钟东蕃 Zhōng Dōngfán), was convicted in 2010.

Beijing did nothing to get Chi Mak out of his 24-year sentence in a federal prison. Rather than trade him for one of the CIA spies Beijing caught in the early 2010’s, they executed the American agents leaving Chi Mak to die in the Federal Correctional Institute at Lompoc, CA, on Halloween 2022.

“They don’t seem to care very much about their operatives,” Brazil said.

Beijing appears to have adopted a flood-the-zone strategy whose danger is hard to downplay.

“The Chinese make up for their unsophistication with hard work,” Eftimiades said. “They are just throwing numbers at the problem. The MSS has bad tradecraft. It doesn’t matter. They are going after so many people, and an intelligence service can be crippled by just a single spy within it.”

Historically, non-democratic, centrally-planned governments have excelled at gathering information but fallen short when knowing what to do with it because analysts tasked with making sense of the collected data don’t feel free to speak their minds.

“Bad analysis is inherent to communist regimes. In communism, politicization is particularly severe. Intelligence officials could not say Marxism is failing,” Maddrell said.

“What the Cold War shows is that the open societies did better, but only because they did better at analysis. Open societies won the Cold War because they were better at analysis…hands down, the Communists won the human intelligence and technical intelligence war. The West won only because they understood the intelligence better.”

Influence

Much of the recent concern over Chinese intelligence has revolved around influence operations, particularly the idea that TikTok ultimately answers to the CCP. Donald Trump’s order banning the app vaguely cited influence as his reason, a line of thinking that has been largely preserved by the U.S. intelligence community under the administration of his successor, President Joseph Biden.

“Beijing is intensifying efforts to mold U.S. public discourse — particularly by trying to shape U.S. views of sensitive or core sovereignty issues, such as Taiwan, Xinjiang, Tibet, and Hong Kong — and pressure perceived political opponents,” said the February 2023 Annual Threat Assessment from the office of the Director of National Intelligence.

Paul Heer, a former U.S. intelligence official working on China as a fellow at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, said that there are few signs that Beijing’s influence operations in the U.S. are worth worrying over.

“I am not that concerned with their influence…it is not that effective,” Heer told The China Project.

One does not need to be an expert to realize that China’s influence operations show little sign of threatening the U.S. Over the last decade, since Xí Jìnpíng’s 习近平 rise to the role of China’s paramount leader in 2012, American public opinion of China has grown significantly more negative. An April study by the Pew Research Center shows that the number of Americans with an “unfavorable” view of China rose from 36% in 2011 to 83% today.

What positive influence Beijing did have in Washington has largely been squandered. American business used to temper Washington’s mistrust of Beijing, said a source close to the U.S. business community in China. Despite frictions such as trade imbalances, intellectual property theft, and human rights violations throughout the 2000s and into the early 2010s, large American corporations “asked D.C. to give China some space.”

But Beijing’s spies hacking into the computers of those very companies that asked Washington to cut China some slack, soured them on China. Now, the source said, American businesses are quietly cheering on officials bashing Beijing. “China went too far. China earned this, China is responsible for this.”

HR Nightmare

China’s spies who have made cyberhacking their primary modus operandi have been a much greater threat to American security than TikTok and spy balloons combined.

In what is arguably the worst security breach in history, the Chinese hacked the U.S. government’s human resources department, the Office of Personnel Management (OPM).

In November 2013, Chinese hackers began snooping around OPM systems. By March 2014, the OPM realized that Chinese hackers were inside , but the OPM thought the hack was contained. On May 27, 2014, the OPM conducted what it called the “Big Bang,” a major reset of their system to clean out attackers. But it was too late. Chinese hackers had already installed malware to create a backdoor into the OPM system.

It was not until almost a year later, on April 15, 2015, that OPM security officials realized they were still being hacked. By that point, the attackers had stolen data on 22.1 million people, targeting those whose applications for U.S. government security clearance made them prime targets and potential assets for recruitment by Beijing.

Each security clearance applicant’s required SF-86 form detailed sensitive information, including health, financial, and criminal records, histories of gambling, sexual partners, and drug and alcohol use — all information that could be used as leverage in blackmail. Also included in what the hackers stole from the OPM were usernames and passwords that could compromise a targets’ other protected log-ins elsewhere on the internet. The hackers even obtained 1.1 million sets of fingerprints.

After the breach was exposed, U.S. officials concluded it was “highly likely” that every file associated with an OPM-managed security clearance application since the year 2000 had data lost to these hackers, data that could easily have helped Beijing target spies such as Kevin Mallory, who they reached out to through LinkedIn.

The OPM hack was only one in a series of damaging hacks begun early in the 21st century, when China realized that, because of changes in technology, they had an opportunity to level the espionage playing field.

“They realized correctly that breaking into someone’s computer system can be a million times more productive — and I say that literally — than breaking into the embassy safe,” Brazil said.

The rise in China’s cyberespionage began in 2003 with Titan Rain, an operation that over two years targeted computer networks in the U.S. Departments of State, Homeland Security, and Energy. Following Titan Rain, there were numerous other Chinese cyber attacks with names like Aurora, which, in 2009, targeted the U.S. high-tech industry, stealing data from Silicon Valley software giant Adobe Systems and Cambridge, MA cloud computing leader Akamai Technologies. Beginning in 2014, Chinese hackers tapped hotel chain Marriott for gigabytes of data, including 327 million passport numbers.

Despite a 2015 agreement between Barack Obama and Xi Jinping to take steps to stem the tide of cyber espionage, after which hacking dropped off for nine months, Chinese hacking continued unabated. In 2017, credit reporting agency Equifax lost the sensitive financial data of about 145 million Americans, a crime for which the U.S. government, by this time embarrassed and fed up, publicly charged ranking members of the People’s Liberation Army, citing a trove of evidence. China denied any involvement.

Though China’s cyber spies are excellent at breaking into American computer systems and stealing massive amounts of data, as with their humint gathering, they seem not to care about covering their tracks.

“China’s hacking is often sloppier and easier to spot,” author Gordon Corera wrote in his book Cyberspies. “Russia’s hackers are more expert and operate below the radar.”

However, James Lewis, senior vice president of CSIS, a Washington think tank, cautions that the Chinese may have been sloppy but they are improving. “They were clumsy and noisy a decade ago. Today, they are almost as good as the U.S. They are still catching up, but they have gotten a lot better.”

Economic espionage with a military bent

Prime among China’s cyberhacking targets are U.S. military technology companies.

The case of Sū Bīn 苏斌 is typical of the economic espionage China conducts against the U.S. Su was a Chinese national living in British Columbia running a successful aerospace company called Lode Tech, living a comfortable Canadian lifestyle and helping his wife raise their two Canadian-born children. Two hackers in China who breached the computer systems of nearby aerospace giant Boeing, in Seattle, worked closely with Su to steal the plans for Boeing’s C-17 Globemaster transport plane. Once the hackers entered Boeing’s system, Su employed his engineering knowledge to guide them as to what they should steal.

In an email bluntly subject-lined “Re: C-17_2,” Su wrote to the spies, “There are many picture documents. The useful ones are marked in yellow. Many documents are for application. They should be the computer documents of a person who uses airplane [sic], not the computer documents of a designer.”

After the hackers had stolen 65 gigabytes of Boeing’s data, Su flew to China to help the spies and engineers interpret the stolen materials. In an email between the two hackers working with Su that appeared in court documents in his case, one hacker explained to the other what China liked to steal from the U.S.

“The focus on the U.S. is primarily on the military technologies, but it also touches other areas….we still have control on American companies like [expunged] and etc. and the focus is mainly on those American enterprises which belong to the top 50 arms companies in the world.”

Joshua Skule, a former head of an FBI intelligence group who now heads his own technology security company, told Reuters in 2018 that approximately 70% of Chinese espionage against the U.S. is aimed at stealing secrets from companies, not the government.

Eftimiades agrees. “The vast majority of espionage is not directed against the national security apparatus, but against commercial companies and technologies with military applications,” Eftimiades said.

American officials are right to complain that Chinese spies are stealing vast amounts of data from American companies, and often complain that this behavior is unique to China.

Michael Hayden, a former director of the U.S. National Security Agency, told Cyberspies author Corera, that while American signals intelligence and Britain’s Government Communications Headquarters also intercept foreign company data, they do so with the sole goal of keeping British and American subjects safe and free:

We don’t steal things to make Americans or, in GCHQ’s case, British subjects, rich. The Chinese do. And they do it on a massive scale. That’s the difference between what free people do in terms of signals intelligence and what the Chinese are doing.

The free peoples of France and Israel might disagree. The intelligence services of these two countries are, behind those of China and Russia, among the most prolific at stealing American economic secrets and handing them off to their own countries’ companies, doing exactly what China does.

It is notable that American intelligence does not retaliate in kind, spreading competitive intelligence gathered in the field to American companies, leaving them instead to compete for themselves in the marketplace. “The U.S. has been unusual in that regard,” said Loch Johnson, an editorial board member of the Journal of Intelligence History.

”What makes China’s economic espionage unique is not the fact that they are doing it but the scale at which they’re pulling it off.”

Back to the Future

With the rise in attention being paid to U.S.-China relations and Chinese spying, it is prudent to remember that trans-Pacific spy wars are as old as the PRC.

John Delury, an American professor of Chinese history at Yonsei University in Seoul, recently published Agents of Subversion about the U.S.-China intelligence relationship in the 1950s. The event at the core of the book involves the capture of two CIA officers who violated Chinese airspace in order to spy. When the U.S. government learns the officers are alive in a prison in Beijing, the State Department lies to the world, claiming the officers died when their plane was downed on a civilian mission. The agents become pawns in a larger standoff and years pass before the American families are informed of the truth.

Delury is concerned that Balloongate and the perceived TikTok bomb may presage a return to a U.S.-China relationship that is more like the 1950s, when the State Department prevented American citizens from going to China and China sank into thirty years of centrally-planned self-destruction. With hostility and paranoia increasing on both sides, interest in espionage has become “the new normal,” said Delury, quick to remind that even during the brief, best years of U.S.-China relations, in the 1980s — before 1989 — and then again the 2000s, neither side quit spying on the other.

Delury wonders if officials on both sides can manage the relationship in a responsible way to prevent it from backsliding into the past. “The question is how bad is it going to get and how low is it going to go.”

Backsliding?

Chinese espionage in the U.S. is dangerous, but many experts believe the threat is being overhyped.

Chinese intelligence “is not ten feet tall,” Brazil said. “They are not monster cockroaches gripping knives between their teeth, crawling up our arms. It is just spying.”

The U.S. should treat Chinese spying like Russian spying, according to Brazil. Better counterintelligence work is needed, he said: “The U.S. needs to up its counter-espionage game by hiring more people, with and without security clearance, who speak and read the language and understand the Chinese community. We are at an inflection point and it’s time for major changes.”

Instead of not taking Chinese espionage seriously enough, the U.S. faces the possibility that it is taking the threat too seriously, especially in the run up to the U.S. general elections.

“Some individuals can advance their political careers by creating external enemies,” said Johnson. “Now, we have people who are using China as a way to show their toughness and their masculinity. It works for them. But it is very dangerous. It creates this mythology that we have.”

So why are TikTok and LinkedIn treated differently? Perhaps it’s because Americans have a difficult time imagining that the leadership of the Sunnyvale, CA social network (which employs roughly 21,000 people and is owned by publicly-listed tech giant Microsoft) would be careless enough to expose its 900 million registered users to exploitation by Chinese spies seeking classified information.

Conversely, it is easy for U.S. politicians to vilify and transform TikTok into a Chinese boogeyman in an election season when it is politically expedient to do so. Despite the unbalanced threat assessment, Delury remains hopeful about U.S.-China relations.

“The Chinese people are awesome, and the American people are okay, too, if you get to know us,” he said, noting, thankfully, that since the late 1970s personal connections across the Pacific have blossomed, linking China and the U.S. and acting as ballast against turbulence when it arose in, say, 1989, in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square Massacre, when U.S. companies turned their backs on China, or again in 1999, when the U.S. bombed the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade and Chinese boycotted American businesses.

“There are still deep reservoirs in the relationships Americans and Chinese people have built up,” Delury said, adding a note of caution: “But those connections are on the backfoot.”