A ‘second Gui Minhai’? Taiwan publisher’s arrest in China sets off alarms

Li Yanhe, a.k.a. Fu Cha, is a well-regarded Taiwanese publisher who was detained on a recent trip to Shanghai. His disappearance has sent shockwaves through the Taiwanese publishing and culture industry.

Two months before Taiwan publisher Lǐ Yánhè 李延賀 disappeared in China, Taiwan-based journalist and bookstore owner Zhāng Jiépíng 張潔平 met Li for a meal in Taipei. They discussed his plans to return to his home country for the Qingming Festival.

“He asked me, ‘If I go, do you think it will be dangerous?'” Zhang recalled. “I said, ‘Yes, I think it will be dangerous, you don’t know where the so-called red line is, you don’t know what the logic for arrest is.'”

According to media reports, Li, who was born in China and uses the pen name Fù Chá 富察, was returning to sweep the tomb of his father, who had recently died, and to renounce his Chinese citizenship — a requirement for Chinese citizens under Taiwanese law within three months of gaining Taiwanese nationality, which Li had reportedly obtained. Soon after arriving in Shanghai, Li’s family lost contact with him, but they tried to keep the case quiet. Friends, however, raised the issue on social media. On April 26, China’s Taiwan Affairs Office confirmed that Li was being investigated on suspicion of “engaging in activities endangering national security,” but did not elaborate further.

Li is the editor-in-chief of Eight Banners Culture (八旗文化 bāqí wénhuà), a Taiwan-based publishing house also called Gusa Press, known for printing books on a wide range of nonfiction subjects, from American political philosophy to literature and art. “Eight Banners” references Li’s Manchu heritage, of which he is proud. His press publishes historical texts that challenge the Han-dominant view of Chinese history and takes a viewpoint from the perspective of “Inner Asia,” such as books on Southern Yue identities, the Central Eurasian civilization, and Islam in China.

Gusa Press has also printed many Chinese translations of books directly critical of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), including Louisa Lim’s The People’s Republic of Amnesia and Minxin Pei’s China’s Crony Capitalism.

Li’s disappearance has sent shockwaves through Taiwan’s community of writers, publishers, and booksellers in exile, who were reminded of the 2015 arrests of five Hong Kong booksellers of Causeway Bay Books. One of them, Guì Mínhǎi 桂民海 — a Swedish citizen — remains in custody, having been sentenced to 10 years of imprisonment in 2020.

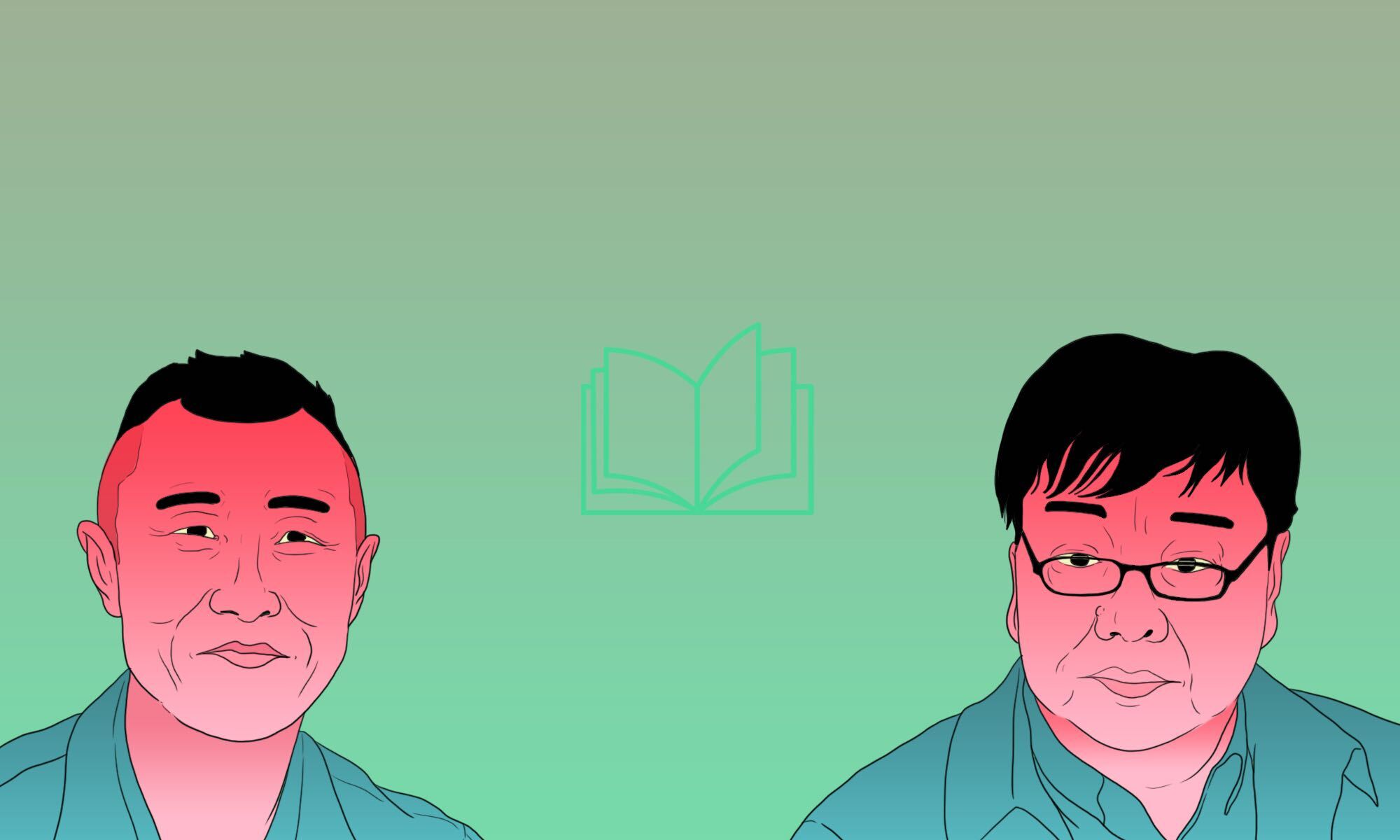

Lam Wing-kee (林榮基 Lín Róngjī), Causeway Bay Books’ owner, now lives in Taiwan and has reopened his shop in Taipei. As visiting Hongkongers stop in to catch a glimpse of Lam and buy books now impossible to find in their home city, Lam says he worries about Li’s fate. Like Gui, Li’s non-Chinese citizenship is unlikely to help his case — particularly since Beijing sees Taiwan as part of its own territory.

“Publishing any book in Taiwan is fine, as long as you’re not planning on going to China,” Lam said. “The traditional idea in China is that anyone born in the Chinese mainland is Chinese…so they might not let him return to Taiwan.”

Bèi Lǐng 貝嶺, a Chinese exile poet who lives in a mountainous hot spring town outside of Taipei, was a friend of Li’s and Gui’s as well as Liú Xiǎobō’s 刘晓波, the Chinese human rights advocate who died after being released from prison in 2017. Bei said advancements in China’s laws since the Causeway Bay booksellers case have worried him, and that Li could become “a second Gui Minhai,” citing language in Chinese reports about Li’s arrest that have called him a “Taiwan independence activist.”

Bei called Li an “intellectual” who was passionate about history and exceptionally good at his job. Before coming to Taiwan after marrying a Taiwanese citizen in 2009, he served as the vice president of a Shanghai publishing house. Bei said that as an editor, rather than a writer producing “controversial” texts firsthand, Li may have believed he was safe from potential detainment upon arrival in China.

“I’m not optimistic about this situation,” Bei said. “I think it will be very difficult for him to explain that he published these books out of love for knowledge and ideas…not Taiwan independence. His attention was much bigger and had a more international view.”

Taiwan’s Mainland Affairs Council declined to elaborate on details of the case and Li’s immigration status and reasons for visiting China. In a statement, the council said that it was paying close attention to the developments of Li’s case and “using existing cross-strait channels to make clear requests to ensure his personal safety and provide support to the family members,” the MAC wrote in response to a request from The China Project.

Li’s detainment is the third such case reported in recent weeks. On April 24, media reported that Dǒng Yùyù 董郁玉, a Chinese journalist who worked for the state media outlet Guangming Daily and was known for his liberal writings, was arrested on charges of espionage in 2022 after meeting frequently with foreign diplomats and journalists. The next day, Yang Chih-yuan (楊智淵 Yáng Zhìyuān), a Taiwanese activist and chair of the pro-independence National Party, was formally arrested on secession charges more than eight months after his detainment.

News of Li’s arrest has prompted international outcry and condemnation from groups including PEN America, the Taiwan Foreign Correspondents Club, and Reporters Without Borders. Last Thursday, the U.S. Congressional and Executive Committee on China condemned the CCP’s “long arm” of censorship, citing Li’s and Dong’s cases.

The news comes amid heightened tensions between Beijing and Taipei after President Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文 Cài Yīngwén) met United States House Speaker Kevin McCarthy in California in early April. Beijing responded with military exercises and incursions into Taiwan’s ADIZ and across the median line.

Zhang, who met with Li before he went to China, was born in China but built a career in journalism in Hong Kong before moving to Taiwan in 2020. The move has allowed her to speak more freely while pursuing her project, Matters, and running a Taipei bookshop.

She says she doesn’t think of herself as an exile. But in the past several years, as China’s red lines have become blurry, she says she wouldn’t dare risk returning to China. The disappearance of Li was only the latest example of a friend or colleague encountering trouble on the mainland. Detainments of Taiwanese in China are hardly uncommon, though it is impossible to know how many Taiwanese today are currently under arrest there.

The arrest is another reminder of the extent to which the CCP is willing to go in order to control narratives about China beyond its borders. Last year, the Thai student publishing house Sam Yan Press, which specializes in books about human rights and democracy, including those critical of China, was offered 4 million baht ($105,540) by a Chinese businessman to shut down operations.

And as “sensitive” books continue to disappear from Hong Kong bookshelves, Taiwanese publishers face a declining incentive to print books that, four years ago, may have sold well in Hong Kong.

“There has been some more caution by Taiwan publishers recently,” said Jeff Wasserstrom, whose book China in the 21st Century was translated into Chinese by Gusa Press. “If thousands of copies [of books] can no longer be sold in Hong Kong because of the market there — both with books being banned but also with more bookstores in Hong Kong being mainland-owned — then there would be a pragmatic reason to publish fewer translations of books on touchy subjects.”

Compared with the response from international organizations and some Taiwanese politicians, Li’s disappearance has drawn a noticeably muted reaction within literary and publishing circles in Taiwan — likely as a result of requests by Li’s family for privacy, said Zhang. Gusa Press has also requested that the family be given space and that the public refrain from circulating rumors. Some likely also see Li’s case as a matter that has nothing to do with them due to his Chinese background.

But Zhang and Bei said keeping quiet about the incident equates to self-censorship and would be a dangerous move for Taiwan.

“We need to understand the threats we are facing and look at how other people have lost their freedom,” Zhang said. “We shouldn’t think this would never happen to us.”