Our weekly explainer series, China Ties, looks at China’s relationship with different countries of the world.

“The China-Kyrgyzstan relationship is now at its best in history,” announced President Sadyr Japarov with a swagger at the China-Central Asia Summit earlier this month, a glossy slogan backed by dark small print in a new strategic partnership signed with Beijing.

It promised to combat “East Turkestan terrorist forces,” including through “suspect repatriation.” Kyrgyzstan was the only Central Asian country to mention “East Turkestan terrorists” at the summit, and is the only one to specifically guarantee repatriation in its partnership agreement.

It puts Kyrgyzstan’s Uyghur community — up to 50,000 strong — under the spotlight in a country that, according to Niva Yau, a Non-Resident Fellow at Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub, has “the most vibrant civil society” in Central Asia. China worries the country’s entrenched system of organizations and activists could make waves across the border in Xinjiang, Yau says. “If there’s any country where this could boil over the top, it would be Kyrgyzstan.”

Today, the country’s a dangerous mix of corrupt elites and eroding civic freedoms, awash with both Chinese debt and valuable, underexploited natural resources — something Chinese companies salivate over.

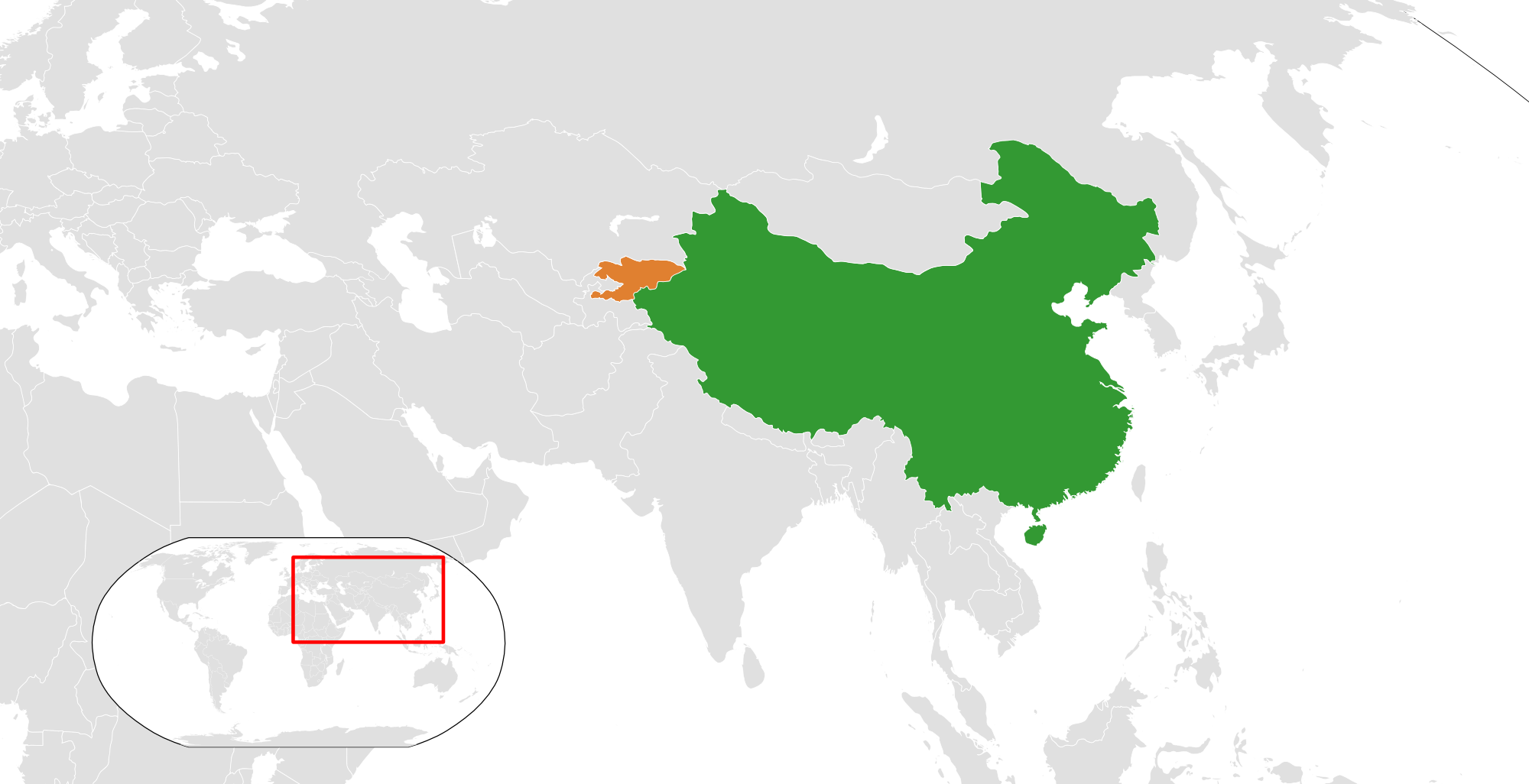

Geography alone was enough to attract China’s attention, sharing a 1,000-kilometer border along southern Xinjiang. Even when Kyrgyzstan emerged from the USSR as an independent state in the early 1990s, one of the first major treaties the two signed was a joint agreement in 1996 promising not to interfere in each other’s domestic affairs, and to patrol each other’s borders (although this didn’t stop Xinjiang’s ethnic conflicts spreading into Bishkek in the early 2000s).

The two countries had inherited fuzzy borders, a relic of the Russian and Qing empires not caring for definite lines in the sand. Only once the border was firmly drawn in 1999 did trading properly begin, growing incredibly fast. From 1992 to 2019, their trade volume increased almost 180-fold, standing at around $15.5 billion in 2022, making Kyrgyzstan China’s second-biggest trading partner in Central Asia. China provided loans for highways and electricity grids, projects that made little money to pay off Chinese debts. China is now Kyrgyzstan’s biggest lender, taking 39.8% of total public debt in 2022, according to the country’s Ministry of Finance.

Kyrgyz Republic

Founded: August 31, 1991

Population: 7 million

Government: Constitutional Democracy

Capital: Bishkek

Largest City: Bishkek

Established relations with the PRC: January 5, 1992

Site of the second-largest iron ore reserve in the world

Deepening relations spelled trouble for the country’s Uyghur community. Uyghur groups reported that after the 1996 non-interference agreement, China made numerous arrests in Xinjiang. A report from the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada in 2015 noted a growing policy of suppression of the nation’s Uyghur rights in tandem with the expansion of China’s economic influence. Yau believes the current restrictions on the country’s civil society are to prevent Uyghurs from speaking against China, pointing to a draft law introduced late last year that if passed would curtail NGOs through restrictive regulations.

Closer ties could also be trouble for the political system. Bribery “is a normal mode of operation in the region,” says Yau, and increased Chinese business in the area will merely fuel corruption. Yau explains that Chinese companies pay a bribe to the right politician for their help or for a meeting, seen by many local politicians as a legitimate “service fee.” The Atlantic Council counted five corruption scandals between 2014 and 2019 involving a Chinese company and a senior Kyrgyz politician. In Yau’s eyes, increased Chinese business on the ground increases a culture of public offices first and foremost “as a money-making business.”

Japarov has made it clear he wants more Chinese business, speaking at the China-Central Asia Summit about the country’s abundant untapped resources. Only a week after the summit, agreements worth $1 billion have been set up with Chinese contractors, from electricity to waste incineration. He floated the idea of using Zhetim Too (the second-largest iron ore reserve in the world, which Japarov estimates to be worth $50 billion) to pay off national debts to China soon after he was elected in 2020. Beijing has repeatedly — as recently as 2021 — demanded ownership of Zhetim Too in return for building railways into Kyrgyzstan. Kyrgyzstan refused each time.

But Russia’s war in Ukraine has made a railway through Central Asia more promising than one through sanction-hit Russia. In September 2022, an agreement on the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway was signed by the three countries, which, if connected up with Turkmenistan, Iran, and Turkey, would shorten the current route from China to Europe by eight days. Each country will be paying a third of the costs. So far Kyrgyzstan has few rails — mostly inherited from the Soviet era. Japarov has said that the country needs them “like air and water,” transforming the country from a dead end into a profitable transit hub. And it is prepared to pay a fifth of the annual GDP for it. Furthermore, on May 12, the government announced that it had found the money necessary to operate Zhetim Too as a mine, but was not clear about where this money had come from.

As with Sudan, China’s non-interference policy provides no framework to restrain political elites from their worst impulses, including exploiting natural resources for personal short-term gain, rather than long-term growth. Many Kyrgyz view Chinese business with distrust — less the way out of their troubles, more a way to pile them on.