Chinese Muslims and police clash over partial demolition of historic mosque

Protesters clashed with police in Nagu, Yunnan Province, on Saturday, as the mostly Hui Muslim residents of this town feared that authorities were commencing with plans to remove the dome and minarets of the historic Najiaying Mosque.

Nothing foretold any trouble on Saturday, May 27, when Hui Muslim residents of Najiaying Village in China’s southwestern province of Yunnan left their mosque at dawn after performing morning prayer. By 10 a.m., however, they saw trucks, cranes, and bulldozers entering the centuries-old mosque’s courtyard.

The vehicles were protected by a special police force that, witnesses reported, numbered close to 400. Wearing dark-color tactical uniforms and carrying riot shields, they blocked the entrance while a construction crew began erecting a scaffold around the mosque façade. A People’s Liberation Army (PLA) unit was also dispatched on-site, with videos showing the military marching through the street leading to the mosque and stopping to stand by around 300 feet away from the entrance.

Protests erupted when local residents feared that this was the start of a long-scheduled “renovation” of the mosque, namely the removal of a domed roof and four minarets.

Clashes are believed to have been ignited when someone spotted a construction crew smashing the decorative fences around the greenery and uprooting the trees. “It was just like the Jewish army humiliating the Palestinians in Jerusalem,” a witness told me. “They got into the mosque courtyard and started smashing everything that stood in the way of the cranes and bulldozers!”

Efforts to break through the cordon lasted until the noon prayer, by which time some people reportedly began publicly professing their willingness to claim martyrdom if they weren’t allowed inside for prayer. Another set of videos show people walking toward the mosque while some throw objects in the direction of the police retreating from the courtyard. “They temporarily left, and the cranes are also removed, thank God,” a male voice says on a video that shows people dismantling the bamboo scaffolding structures.

The incident in Najiaying, part of Nagu Township, was as sudden as it was predictable. Back in April 2020, a photo of an internal document issued by the Ethnic and Religious Affairs Committee of Sichuan Province briefly circulated on WeChat until it was censored. Called “Notice on the rectification of the ‘Arabic-style’ mosques,” it instructed authorities to “pay attention to the means and strategies” in the work of “altering” mosques and “prevent causing contradiction or any incidents of unrest.”

“The campaign is forced, but it has to look voluntary,” one Shadian resident explained to me back then. The resident suggested that the provincial authorities were tasking officials on the ground with implementing the campaign without bringing bad publicity or causing trouble for the upper levels of the government.

The people of Nagu and Shadian I talked to feel they are powerless in the face of the campaign, but they also believe they can potentially delay the implementation of the campaign by talking history with the authorities on the ground and biding time. “On the issue of the mosque’s minarets and the dome,” one Shadian resident said to me, “we want the authorities to understand that it is such similar policies that caused the Shadian Incident.”

Meanwhile, provincial authorities have tried to convince locals that the demolition is necessary. One Shadian resident reported that his wife, who works in the local school, attended a meeting where all the teachers were requested to show support for the “alteration” project.” Absence of their signatures in an internal letter of support distributed by the government, they were told, would be adversely reflected on their paychecks. Authorities also seem to have reached out to the private business owners who sustain the upkeep of the mosque through their charitable donations. “They ask us to show agreement,” one of them said, “and their meaning is that they would open our past tax returns for investigation if we don’t make right decisions.”

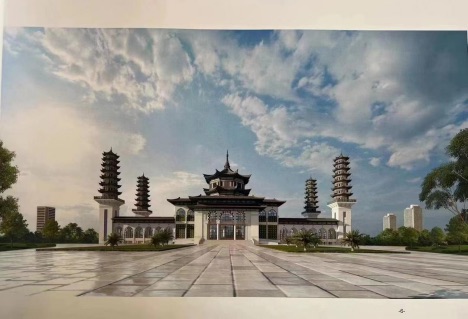

Provincial authorities also formed a working team specifically tasked to conduct ideological work. This Ramadan, which began on March 22, the team stayed in Shadian for two weeks, during which they walked this town of 14,000 residents household by household, showing them the blueprint for the mosque’s new look, featuring seven-tier pagodas in places where minarets stood and an outsized Chinese temple-like stupa sitting atop the main prayer hall. The blueprint was said to have been obtained from the same architectural institute that came up with the existing Medina-style design.

One resident reported that his home was visited twice and that an official from the working team called him twice. “Every time he tells me that this campaign comes from the center and that they have no choice but to implement it,” the resident said. “Last time he asked if I liked the new design and I said I don’t. ‘No rush,’ he then said to me. ‘Let’s discuss this together.’ He was polite. But I know that this is not about showing respect but about power.”

The end of an era

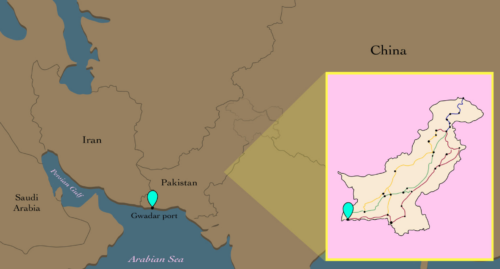

Thousands of mosques across the country have since seen parts of their previously approved architectural features demolished. The Najiaying Mosque and the Grand Mosque in the neighboring village of Shadian are considered to be the last two government-approved “Arabic-style” mosques in China. But their days seem to be numbered. Hui Muslims in Shadian, where I did two years of my ethnographic fieldwork, tell me that the “alteration” of their mosque is scheduled to begin in late June.

The incident over the weekend illustrates the latest development in a state-sponsored campaign to Sinicize Islam, dating back to a religious work meeting that Chinese leader Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 chaired in March 2016.

During that meeting, Xi stressed that religions should merge with the dominant Chinese culture and the core values of socialism. In China’s northwestern region of Xinjiang, the directive morphed into a repressive campaign of assimilation targeting Uyghurs and members of other Turkic minorities. Among the Hui ethnic minority communities across China, the drive often takes the form of alterations to structures that authorities categorize as signs of “Arabization.”

Located around 80 miles from each other, Nagu and Shadian are two affluent and urbanized Hui towns in China’s Yunnan Province. The Hui have inhabited both areas for centuries. Both towns are almost exclusively Hui, and Islamic traditions are widespread in both places (Shadian is the home of Mǎ Jiān 马坚 and Lin Song, two scholars who gave the Hui full-book Chinese translations of the Quran). The mosques of these two towns also occupy a special place within the landscape of Chinese Islam.

The Shadian mosque is a replica of the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina, Saudi Arabia. With three prayer halls and the capacity to accommodate 10,000 worshipers (roughly two-thirds of the town’s population), it claims to be the biggest mosque in China. Constructed in 2010 on local donations, this structure bears the name of the Ming-era Grand Mosque, also located in the city, which was destroyed in 1975. At that time, the communal resistance to the iconoclastic policies of Mao resulted in a military intervention that claimed the lives of more than 1,400 residents. The massacre was officially redressed in 1979 and became widely known as “the Shadian Incident.” Today, local residents refer to the victims of this ethnoreligious violence as “martyrs,” while the town had until recently been marketed by the authorities as a “national level Hui Muslim tourist destination.”

Nagu, on the other hand, is a center of Islamic education. Many clerics currently serving in Hui hamlets across the province graduated from the madrasa that is attached to the Najiaying Mosque. The mosque was also constructed with charitable donations from the community and went into service in 2004. With the capacity to accommodate two-thirds of the town’s 5,000 residents, the mosque is second to Shadian’s in size. In 2018, it was included in the county-level list of “cultural relics.”

Both mosques enjoy high prominence among the Hui, and their Arabic-style design was approved by the authorities at the time of construction. The minarets of these two mosques are a symbol of Islam but also of the multiculturalism that developed during reform-era China. Their demolition would likewise symbolize the end of a certain era of religious and ethnic governance.

“Since the campaign reached Yunnan in 2019,” one resident of Shadian told me, “authorities were keeping a close eye on the Najiaying and Shadian mosques. They know how special these two places are.”

So far, however, they have been telling the mosque management committees that they will not alter the mosques unless most of the residents agree. Most of the residents, of course, disagree. The sudden deployment of a large police team and a PLA unit in Najiaying this Saturday showcases an attempt to resolve the emergent stalemate through a show of force and intimidation.

But the attempt backfired. In Najiaying, videos from the scene on Saturday show crowds clashing with the police. Some throw water bottles and other objects while others snatch riot shields and push through the cordon to get into the courtyard of the mosque. Women can be heard wailing.

These acts of spontaneous yet collective resistance are rare in China, where the state values, above all else, “stability maintenance.” But they do happen. In August 2018, the Hui in Weizhou in northwestern Qinghai Province protected the demolition of their mosque through a large-scale sit-in protest, but they didn’t engage the police. In Najiaying, shortly before the confrontation, crowds faced the PLA unit and chanted “Allah is great” and “There is no God but Allah” in Arabic.

“A serious disturbance of social management”

On the morning of Sunday, May 28, the public security bureau and the people’s court of the county where Najiaying is located jointly published a notice. It began with a claim that “a serious disturbance of social management occurred in Nagu Township, Tonghai County, resulting in an adverse social impact.” It then requested that “organizers and participants of activities that disrupt public order surrender themselves and confess the facts of the offense.” It further mentioned that a “zero-tolerance” approach will be adopted in “cracking down on crimes against the social order.”

Reading the notice with me over the phone, one resident gave a crash course in Chinese politics: “The usual scenario in such situations is first to arrest and convict a couple of people as a way to intimidate the public. The authorities will then send working teams to do door-to-door ideological work. Finding some enthusiasts, they will use them as an example to break those who are not clear in their stance. After that, they will round up all those whose stance is firm. After that, the end!”

Meanwhile, residents of Shadian reported that the streets of their town were patrolled by militia on Sunday. A heavy police presence was also spotted on the expressway entrances closest to Shadian. To prevent local Hui from going to Nagu, officers were stopping private vehicles and asking where people were headed.

Among the mosques in Yunnan with the “Arabic” design that was previously approved by the government, those of Najiaying and Shadian are the last ones to remain un-rectified. After the dramatic events of Saturday, both communities are coming to terms with the fact that the removal of the domes and minarets from their mosques is imminent.

Rumors from Nagu at this point say that authorities have decided to postpone renovations until early next month, since the community will gather in the mosque’s courtyard on May 30 to send this year’s pilgrim delegation to Mecca for Hajj. Shadian, on the other hand, sent their delegation on May 29. The pilgrims left their hometown in despondency: They will probably come back to witness the Grand Mosque of Shadian missing its minaret and dome. The “alteration” work is scheduled to begin in late June, after the Sacrifice Feast celebrations are over.