China’s first civilian in space, and maybe a man on the Moon

With three new astronauts on its space station and a promise to put people on the Moon by 2030, China took another step toward advancing its goals of becoming a major space power by 2045.

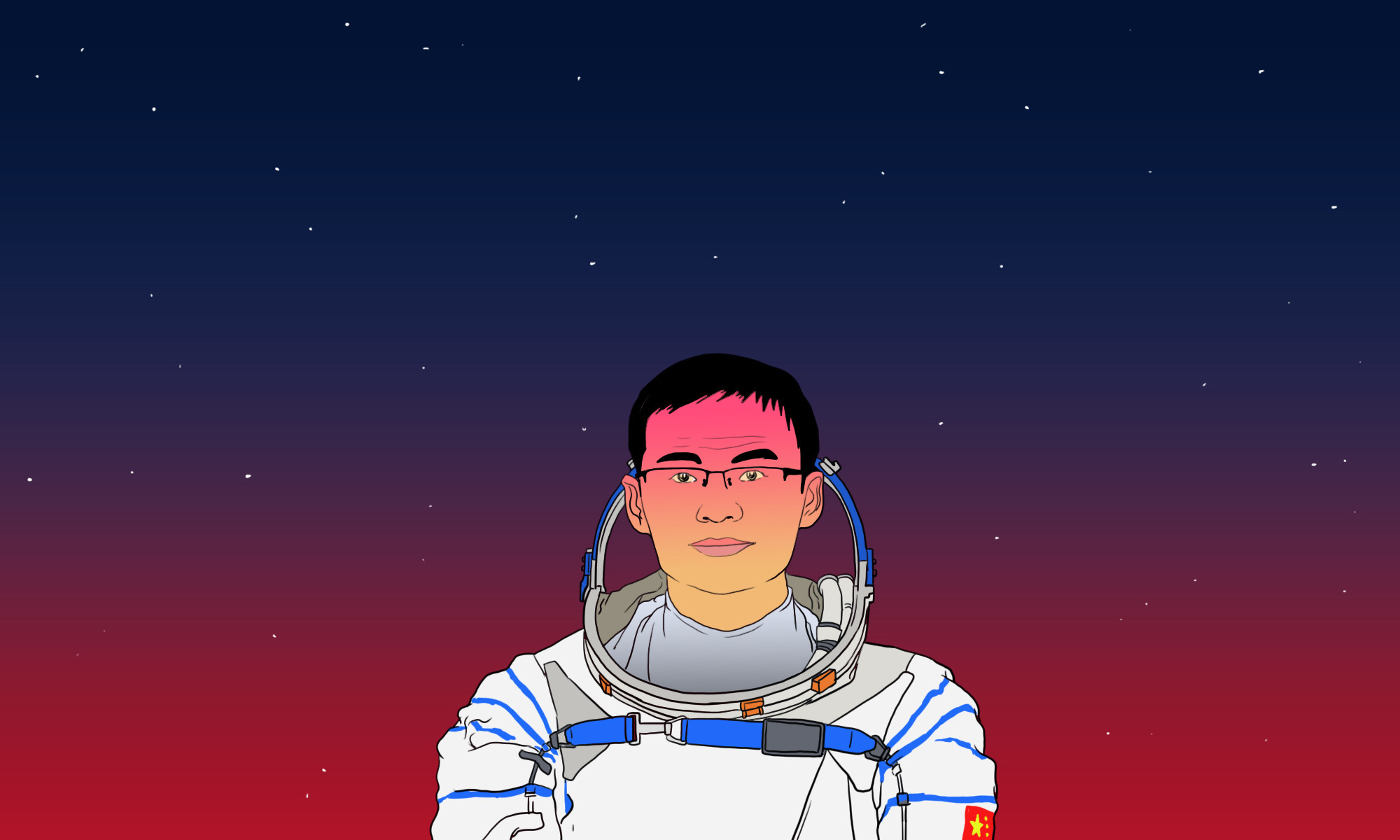

China sent its first civilian astronaut to space as part of a three-person crewed mission to the country’s newly completed Tiāngōng 天宫 (“heavenly palace”) space station, the China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) announced at a press conference (in Chinese).

The Shenzhou-16 spaceship launched from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in the Gobi Desert at 9:31 a.m. Beijing time on May 29, before successfully docking at the Tiangong space station about five hours later. It is the fifth manned mission to the Chinese space outpost since 2021, and the first since the station was fully completed in November 2022.

The three crew members, Jǐng Hǎipéng 景海鹏, Zhū Yángzhù 朱杨柱, and Guì Hǎicháo 桂海潮, will take over from the Shenzhou-15 astronauts, who have been abroad the space station since November. The new crew will spend five months aboard the station conducting spacewalks, assisting with the docking and departure of cargo and other spacecraft, and carrying out scientific experiments.

The mission will be the fourth for veteran astronaut Jing, but the first for spaceflight engineer Zhu and payload specialist Gui. Bespectacled Gui, a professor at China’s prestigious aeronautics institution Beihang University, is the first Chinese civilian to be put in orbit. All other astronauts have been members of China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) — and those with myopia were long seen as disqualified in the running to become astronauts. But since 2017, China has updated the recruitment process for its space program to allow individuals with low-degree myopia to be considered as viable astronaut candidates. Gui’s expertise as a payload specialist, primarily responsible for experiments in orbit, follows a recent pattern of similar astronaut selections that indicate a new phase of development in the country’s space program.

“This mission continues the steady progress of China’s human spaceflight program. They are demonstrating that they can run full-scale space station operations, to the point of having a scientist astronaut fly to dedicate time to research work,” Leroy Chiao, a retired National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) astronaut and ISS Commander, told The China Project.

At the press conference, Lín Xīqiáng 林西强, the deputy director of the CMSA, also announced (in Chinese, English) official plans to place astronauts on the Moon before 2030, and to carry out lunar scientific exploration and related technological experiments. While Chinese authorities have previously signaled those ambitions in the past, Lin’s announcement marks the highest-level confirmation of China’s ambitions for a crewed lunar landing: Last month, Wú Wěirén 吴伟仁, chief designer of the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program (CLEP), told state broadcaster CCTV that setting foot on the Moon by 2030 is “not a problem” ahead of the country’s national Space Day on April 24.

“Fundamentally, this suggests that Chinese space activities are starting to be more about doing interactive science in space, which requires scientists and engineers, rather than just claiming the badge of human space flight or placing experiments in orbit,” Chad J. R. Ohlandt, a senior engineer at the RAND Corporation who studies foreign aerospace industrial policy and programs with an emphasis on Asia and China, told The China Project.

China’s big space dreams to the Moon

A manned lunar landing would be a major milestone in space exploration for China and the world. China is the only country to have successfully landed on the Moon in the 21st century, and in 2019, it became the first to land a probe on the Moon’s far side. No human has set foot on the Moon since the U.S. conducted its Apollo missions in the 1960s and 1970s.

“China rarely announces something to the world that it is not 100% committed to. If they say they will do a thing, then if you look at what happens next, it tends to come to pass,” Quentin A. Parker, the director for Laboratory for Space Research at the University of Hong Kong, told The China Project.

In 2003, China became the third country in history to launch a human into space after the former Soviet Union and the U.S. The country has been developing its space program ever since: Chinese leader Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 has reiterated calls to transform the country into a leading “space power” by 2045. A 2022 government white paper states that “the space industry is a critical element of the overall national strategy,” and its development has become a point of national pride that embodies China’s economic rise in the past four decades. Rocket launches off the tropical island of Hainan and arid sites in the Gobi Desert have become popular destinations amid a booming space tourism industry, drawing in crowds to witness the symbol of the country’s technological self-reliance.

A completed space station

Meanwhile, orbiting about 390 kilometers (242 miles) above Earth’s surface, the Tiangong space station was completed last November with the addition of the third and final module. Plans to expand the existing station have already been announced.

The space station consists of three parts: Tianhe, the main habitat for astronauts, and Mengtian and Wentian, two modules dedicated to hosting experiments such as research in biotechnology, microgravity, and space materials science. The entire station is able to support three astronauts, or up to six people during crew rotations.

China built its own space station after it was excluded from the U.S.’s International Space Station (ISS) in 2011, largely due to concerns from American officials over the Chinese space programs’ ties to the PLA. Under the Wolf Amendment, Washington prohibited all researchers from NASA from working with those affiliated with a Chinese state enterprise or entity. Some American scientists have boycotted NASA conferences due to its rejection of Chinese nationals.

“China will welcome astronauts from other countries to enter its space station to conduct experiments,” Jì Qǐmíng 季启明, the assistant director of the CMSA, said last December. “Tiangong is the first of its kind open to all UN member states,” he added.

China hopes that Tiangong will replace the ISS, which is due to be decommissioned in 2031. Chinese officials have reported that they have signed agreements and carried out cooperation projects with France, Germany, Italy, Russia, and Pakistan, along with other space agencies or organizations. China also announced plans last November to begin training foreign astronauts to fly aboard Tiangong, though further details have yet to be released.

More civilians to do science in space?

The decision to include the civilian Gui comes as China continues its campaign to open up its space industry to private companies, an effort that began in 2016. Some estimates have claimed that investments are pouring in at over 10 billion yuan ($1.5 billion) a year. The European Space Agency (ESA) reported that, over the past seven years until 2021, well over 100 companies have been created and around 40 billion ($6.5 billion) has been raised by Chinese commercial space companies.

“I believe civilians on the [Chinese Space Station] will be commonplace in the future…because [it] is basically a huge science laboratory and will host many international scientific and technological experiments. These will often be sophisticated, complex, and delicate,” Parker told The China Project.

“To operate and fix such equipment needs deep technical know-how, fundamental and extensive research experience, and deep knowledge of the scientific method,” Parker added. “These skills and experience are not normally found together in the right strengths for ‘taikonauts’ (a Western term for a Chinese astronaut) from a military background. However, they can be found among our academic and government and industrial lab professional scientists.”

Competition with the U.S. on the final frontier

The dual objectives of landing people on the Moon and operating an international space station are significant for China’s growing rivalry with the United States in outer space. While China still lags behind the U.S. in spending, as well as the number of active satellites and launch pads, it is catching up. China’s space program has advanced at a rapid pace in recent years, whereas America’s has often faced setbacks due to conflicting priorities and changing administrations.

“[China’s] timeline appears ambitious for such a complex feat, but it is understood that the various hardware needed to get astronauts safely to the Moon and back is already in development, including a new crew-related heavy-lift rocket, a spacecraft capable of deep space operations, a lunar lander, a rover, and an exploration astronaut suit,” Andrew Jones, a Helsinki-based reporter who has extensively covered China’s space program, told The China Project.

NASA has also announced a plan to put people on the Moon again by 2025 after more than five decades. But the plan, known as the Artemis program, has run into delays. Beijing and Washington have also outlined similar aims of building a research station on the Moon and landing people on Mars.

“There will be a number of technological and other hurdles and variables, but China is committing to its own long-term lunar program in parallel to the U.S.’s Artemis program. This will have a number of geo- and astropolitical ramifications as the decade progresses,” Jones added.

In March, the White House proposed a $30 billion annual budget for its Space Force, a military department established in 2019 by then president Donald Trump, almost $4 billion more than the previous year.

The U.S.’s Office of the Director of National Intelligence’s (ODNI) 2023 Annual Threat Assessment released that same month stated that “China is steadily progressing toward its goal of becoming a world-class space leader, with the intent to match or surpass the United States by 2045…China’s space activities are designed to advance its global standing and strengthen its attempts to erode U.S. influence across military, technological, economic, and diplomatic spheres.” China stated in its white paper that its objectives are only for “peaceful purposes” and that it “opposes any attempt to turn outer space into a weapon or battlefield or launch an arms race in outer space.”

The ODNI report warned of China’s lunar ambitions, as well as its growing number of communications systems. Both countries have been racing to build up their rival satellite communications networks, supported by a swath of ground stations all over the world. Just this past month, China launched a satellite for its BeiDou navigation system, a rival to the U.S.’s GPS, on May 16 — the first time it had done so in nearly three years. Meanwhile, SpaceX, the California-based aerospace company co-founded by Elon Musk, launched 52 more of its broadband satellites on May 31.

“[China] shows a long-term commitment, and its aim is to be the dominant spacefaring nation in the future. It is up to the U.S. to continue our commitment to human space exploration, to continue our lead,” Chiao told The China Project.