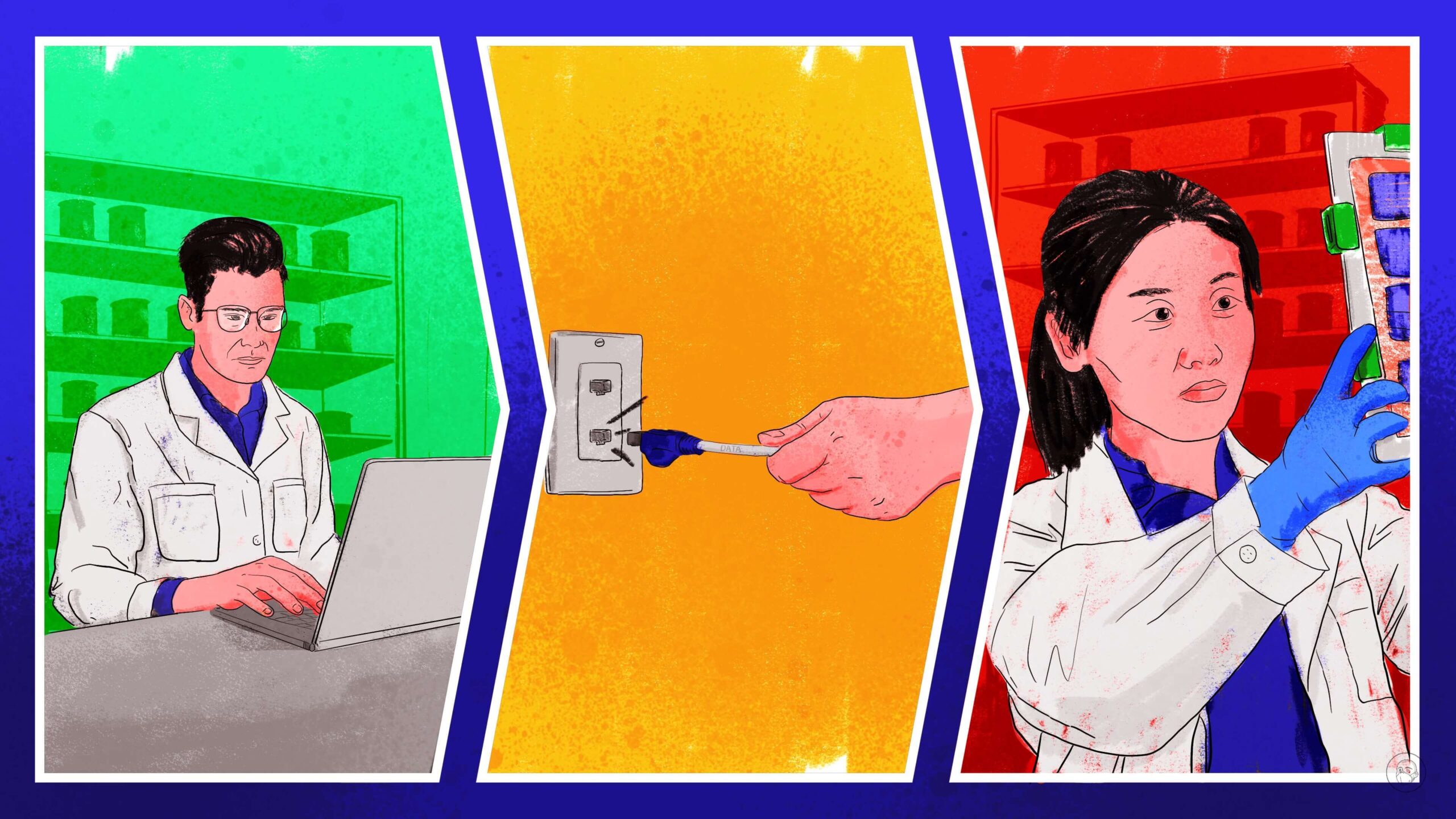

Cut off from China’s data and info, overseas academics, analysts get crafty

People who work with and on China in science, business and government are finding new ways to stay informed in spite of new hurdles and risks.

Three months after China began to block anybody outside its borders from accessing major databases key to global scholarship and commerce, international researchers are scrambling to work around the dearth of accurate information coming from inside the world’s second largest economy.

In April, the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) platform, cut Georgetown University and the University of Notre Dame, to name but two of its 1,600 institutional users outside of mainland China, off from some of its database of statistical and academic publications.

Researchers in the hard sciences also use CNKI in their work. A 2013 master’s thesis by a Chinese student, downloaded from CNKI, was a crucial source for scientists in India who published a 2020 paper on the origins of COVID-19. Under China’s information block, it’s impossible to download that master’s thesis and others like it from accounts outside China.

U.S. government agencies and think tanks historically relied upon the Chinese corporate database Qichacha, citing its information in reports on China’s space capabilities and its corporate social credit system, both from the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission in Congress. Qichacha data also was cited in a report on China-Russia defense trade from the research organization Center for Advanced Defense Studies.

Since April, Qichacha has prompted users to input a Chinese phone number for verification before allowing access, making it hard to verify the meat of many of the U.S. government reports.

Overseas users also report losing access to one of China’s top financial data providers, Wind Information. Corporate database website Tianyancha does not open unless the user’s IP address is in mainland China.

China walling off its information started in September 2022, when the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) began implementing regulations that require the review of major exports of data.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

To put the sweep of China’s export restrictions in perspective, imagine if the U.S. refused outside entry to the JSTOR academic database, the corporate database Crunchbase, and the market intelligence firm ZoomInfo all at once.

The China Project reached out to CNKI, Qichacha, Tianyancha and Wind Information. None responded to requests for comment.

Data from Taobao?

CNKI’s international users lost access to master’s and doctoral theses and dissertations, a database of conference proceedings, the national population census of China, as well as the platform’s statistical yearbooks, which offer information on a wide range of economic, social, and environmental topics.

Despite the restricted access to Chinese databases, researchers told The China Project that they have been able to continue their work.

Straton Papagianneas, whose Leiden University doctoral work is on the intersection of technology and governance in China, has been able to continue using the sections of CNKI most crucial to his work. “It has always been difficult to find particular documents, but it is part of the job,” Papagianneas told The China Project.

Studying China’s policies has always been a challenge. Historically, it has not been uncommon for some Chinese government agencies to stop publishing information and data, intermittently.

“It’s just a constant battle,” Victor Shih, Director of University of California San Diego’s 21st Century China Center, said. “You have to figure out a way to make the data comparable, or in cases where data series get canceled, you have to figure out alternative ways to measure certain concepts that you’re interested in.”

Taylor Loeb, a senior analyst at the research firm Trivium China, expressed the can-do spirit many researchers adopt when looking for good information from China.

“If something is online somewhere in the world, disciplined researchers will be able to access it,” Loeb said.

Workarounds for accessing some of the restricted resources exist. Researchers may use virtual private networks (VPNs) to browse the restricted Chinese databases on the Internet from a Chinese IP address — a tactic Chinese travelers abroad often use to access Chinese language movies and TV on the iQiyi platform unavailable outside China.

Some of the restricted information from the blocked Chinese databases is available for a fee from vendors on Chinese ecommerce sites such as Taobao, but this only works if researchers can read Chinese and understand Chinese websites’ different user interfaces.

Restrictions on online resources are not the most important problem facing foreign researchers hoping to understand China.

“The bigger issue is the closing space for reciprocal research more broadly in both the U.S. and China,” said Loeb.

“Online research will never be able to match on-the-ground research, and the on-the-ground environment has been deteriorating steadily for a long time, even before COVID. That lack of firsthand experience and people-to-people exchanges is the real tragedy.”

Balancing risks

In May, The Wall Street Journal reported that research conducted at the Washington-based think tanks Center for Strategic and Emerging Technology (CSET) and Center for a New American Security (CNAS) contributed to Beijing’s decision to wall off some data. The research dealt in part with topics Beijing deems sensitive, such as the Chinese military’s use of AI technology.

The developments highlight the risks that come with conducting and publishing open source research on sensitive topics inside China.

“While the changes in access to public data are dismaying, our research work has continued,” Tessa Baker, CSET’s Acting Director of External Affairs, said in an email.

The measures could have unintended consequences for Beijing, Baker warned, such as amplifying analysts with one-sided views of China.

“Losing access to Chinese data may lead to, for example, exaggerated perceptions of China’s technical advances and capabilities based on hearsay and anecdotes, preventing accurate assessments of geopolitical risk,” Baker said.

While there are risks to openly publishing information on touchy subjects for Beijing, Mark Witzke, a senior research analyst at the independent research firm Rhodium Group, said researchers shouldn’t let that stop them.

“If the data is open and accessible someone is going to use it eventually so researchers shouldn’t hold back,” Witzke said.

Some researchers looking at topics considered sensitive by the Chinese Communist Party were more vulnerable than others, especially those whose family members or friends still reside inside China.

“I think it’s our duty as scientific researchers to maintain the integrity of our work, and I would personally not compromise on these things just because of the fear of losing access,” Papagianneas said.

In addition to the regulations on data exports, China recently revised its anti-espionage law “to expand the scope of targets of espionage, with all documents, data, materials, and articles” related to national security. The revised legislation does not define the scope of national security or China’s interests and further raises the risks of sharing information across China’s borders.

“The revised anti-espionage law, which now has very vague language, says even if the information that you access is publicly available, it could be a national security violation,” U.C. San Diego’s Shih said. “If certain data are sensitive, the Chinese government should really feel free to just remove it from the public domain, instead of creating this very vague, threatening thing for foreigners.”

Wavering confidence

Since the majority of COVID-19 restrictions were lifted earlier this year, Chinese leaders have been making efforts to assure investors that China welcomes foreign investment — but the data restrictions could work to counteract those reassurances.

In late June, Chinese Premier Lǐ Qiáng 李强 expressed support for economic globalization at a global entrepreneurs’ conference in Tianjin. Li aimed to boost the confidence of foreign investors and emphasized that “investing in China means choosing a better future.”

Li’s words were cold comfort to the business community considering that in addition to restricted access to data and information, Chinese authorities have recently conducted raids on the offices of international consulting firms.

In March, U.S.-based corporate investigations company Mintz Group reported that Chinese officials detained five Chinese staff at their Beijing office, then, in April, Chinese authorities visited and questioned employees at the Shanghai office of consulting firm Bain & Company.

In June, the European Chamber said that three out of five companies surveyed noted that the business environment has become “more political”.

“It will be much more difficult for China to convince foreign businesses to be involved in its economy and for other countries to trust China,“ Witzke said.

Additional sources and data

A portal to China is closing, at least temporarily, and researchers are nervous / South China Morning Post

China’s top financial data provider restricts offshore access due to new rules / Reuters

China’s cyberspace regulator says data export review rules effective Sept. 1 / Reuters

李强出席世界经济论坛全球企业家对话会 / People’s Daily

中国有关部门对贝恩上海办事处员工进行问话 / Wall Street Journal

Mintz Group: 5 staff detained in Beijing after raid / BBC

EUROPEAN CHAMBER REPORT FINDS SIGNIFICANT DETERIORATION OF BUSINESS CONFIDENCE IN CHINA / European Chamber

Companies

Wind Information 万得信息网

Qichacha 企查查

Tianyancha 天眼查

Aiqicha 爱企查