Our weekly explainer series, China Ties, looks at China’s relationship with different countries of the world.

Chile was the first South American country to pass a number of milestones with the P.R.C., from diplomatic recognition back in 1970 and backing its entry into the WTO in 2001 to signing a free-trade agreement with the country in 2005. Through a policy of free trade and non-interference, Chile has consistently led South America in China relations. But prosperous partnerships aren’t always trusting ones.

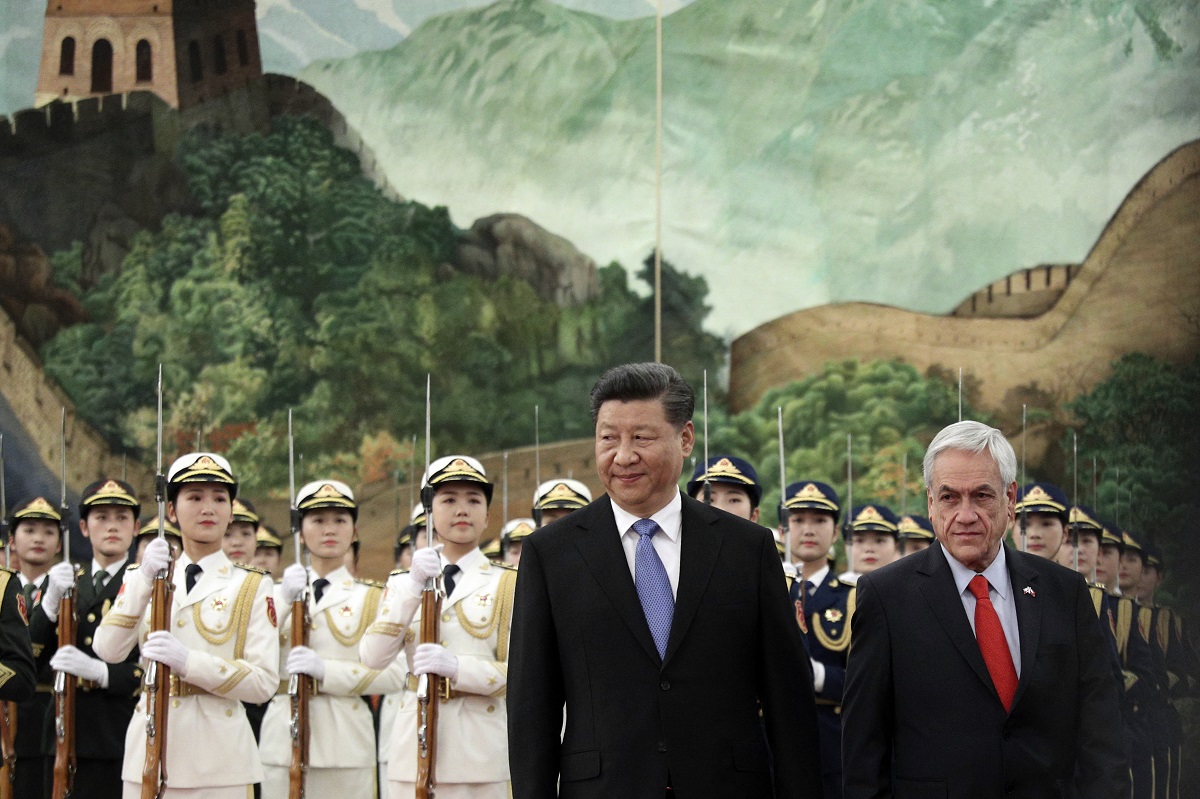

Marxist President Salvador Allende recognized the fellow Communist country when he came to power in 1970, at a time when the P.R.C. was slowly emerging from its isolation and trying to win diplomatic partners away from Taiwan. Warm words continued from 1973 to 1990 in the long and brutal dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet, despite his ruthless anti-Communist agenda.

But these bedfellows weren’t as strange as they seem. Both sides were pursuing totalitarian politics and free-market economics. Both needed foreign friends and trading partners. Pinochet wanted allies after overthrowing Allende in a military coup, while China did not want Taiwan to step into the breach if it broke off relations.

Republic of Chile

Founded: February 12, 1818

Population: 19.6 million

Government: Constitutional Democracy

Capital: Santiago

Largest City: Santiago

Established relations with the P.R.C.: December 15, 1970

There were other benefits to staying allied with Chile. In 1984, China began building the “Great Wall” station, its first research base in Antarctica, on Chilean-claimed territory at the tip of the vast Antarctic peninsula that stretches close to Chile’s borders. The story fits neatly into the usual propaganda molds of Chinese grit impressing foreigners, but omits how much help Chile (along with Argentina) gave the venture.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Chile ambitiously expanded its trade links abroad, while pursuing a policy of non-interference in the domestic affairs of their trading partners, which suited China just fine. Chile has now signed the most cooperative agreements of any South American country with China.

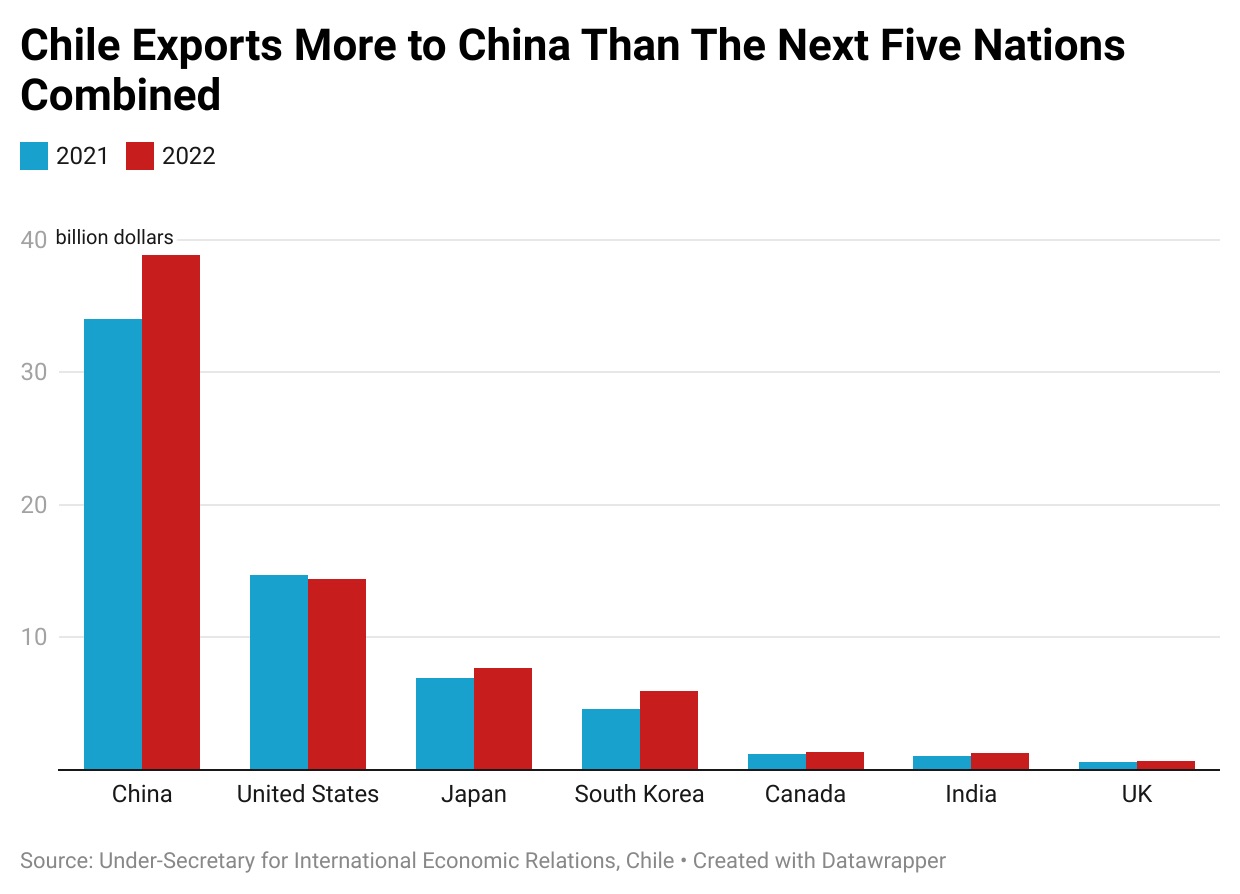

China has invested heavily in Chile. Take a major $2 billion agreement in 2005 between Chilean copper giant CODELCO and Chinese counterpart Minmetals, with CODELCO agreeing to send Minmetals 55,750 tons of copper every year for 15 years. Deals like these made Chile China’s largest supplier of copper (crucial for making solar panels and wind turbines), shipping $9.3 billion worth of the metal in 2022.

Such deals means China is economically integral. In 2022, Chile exported more to China than its next five national trading partners combined.

Key parts of domestic infrastructure are also tied up in Chinese companies — including 57% of electricity distribution — along with local produce. In 2021, local newspapers noted an uptick in Chinese companies buying up Chilean arable land, vineyards, and fruit orchards, sometimes shipping as much as 90% of produce back to China.

But all this means Chilean elites secretly view China with “mistrust and fear” due to how much leverage they now have, writes Pamela Aróstica Fernández, the director of the China and Latin America Network (REDCAEM), in a recent MERICS report.

The fear was real in 2018, when Chinese company Tianqi Lithium wanted a 32% stake in the chemicals company Sociedad Química y Minera (SQM), making it the second-largest shareholder of this major Chilean lithium mine, as part of a Chinese drive to expand the national electric car industry.

Lithium’s importance to electric car batteries is as important as Chile is to the lithium industry, accounting for around 44% of the world’s known deposits. Chilean authorities delayed the deal, concerned Chinese business could go behind their backs and start buying SQM’s goods below the market price, tanking any tax revenues in the process (as happened with Chinese mining companies in the D.R.C.).

It got heated enough for the Chinese ambassador to warn of “negative influences” on Chile’s relationship with China. After several months, Tianqi eventually got 24% for $4 billion, but only once Chilean authorities had ordered no Tianqi executives or workers could sit on SQM’s board, and no sensitive information be passed to them. In 2020, Chile also turned down a bid from Chinese telecoms giant Huawei for a trans-Pacific fiber-optic cable that would have landed in Shanghai, amid a U.S. campaign to freeze Huawei out of global projects, suspecting it of espionage.

Copper prices have taken a downturn this year due to a slump in China’s economy (and when China bought 52% of the world’s refined copper last year; if the country sneezes, the world’s copper trade catches a cold), but BNamericas notes no shortage of projects. Tianqi is lobbying to increase its SQM stake, while in 2021, automobile manufacturer BYD bid $61 million to mine 80,000 tons of lithium beneath the Atacama Salt Lake — although this was suspended by the local governor, fearing pollution.

Despite these differences, in the end, the two countries have always maintained a mutually beneficial, win-win relationship. For China in the West, that might as well describe a friendship.