Deepening divisions across Southeast Asia give China leverage

ASEAN’s leading role in Southeast Asia, a key battleground for influence between major powers, and the bloc’s nominal unity have been seriously eroded in the face of China’s rising clout, with considerable geopolitical implications beyond the region.

Deepening divisions among Southeast Asian states reflect China’s growing leverage in the region as it takes a tougher line toward the U.S. over Taiwan and other territorial claims, according to academics and former senior diplomats.

In recent weeks, Cambodia effectively vetoed Indonesia’s proposal for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to stage its first-ever joint exercises in the contested South China Sea. Meanwhile, Thailand broke ranks with ASEAN to engage the Beijing-backed junta in Myanmar.

“Both Cambodia’s resistance to an ASEAN maritime exercise and Thailand’s hosting of a meeting to discuss how ASEAN can reengage the Myanmar junta undermined ASEAN unity and goals,” said Scot Marciel, a former U.S. ambassador to ASEAN, Indonesia, and Myanmar and the author of Imperfect Partners.

Cambodia: China’s ally in the South China Sea

The South China Sea is increasingly a flashpoint of tensions in the region, alongside the Taiwan Strait, where China is regularly sending fighter jets and warships to intimidate Taiwan. China’s claims over the South China Sea are contested by Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Taiwan, with each having its own claims to various islands and reefs.

“We saw how China can have a de facto veto within ASEAN because all it has to do is to lean on one of the most dependent countries — in this case Cambodia — to prevent any kind of functional consensus on issues that affect Beijing’s interest,” said Richard Heydarian, a senior lecturer at the Asian Center of the University of the Philippines.

ASEAN countries were supposed to take part in maritime drills later this year in the North Natuna Sea, an oil- and gas-rich area off Indonesia’s northern coastlines that overlaps with the southernmost area of Beijing’s sweeping “nine-dash line” claim to almost all of the contested South China Sea.

But Cambodia’s strongman Hun Sen vehemently opposed the plans and forced Indonesia to relocate the exercises to the South Natuna Sea.

The drills were supposed to signal that the bloc can shape the region’s security architecture by conducting exercises among themselves, said Heydarian.

“It looks like Cambodia will veto, essentially on China’s behalf, any kind of initiative that is inimical to Beijing’s interest or Beijing’s conception of its interest in Southeast Asia,” he told The China Project, adding that Cambodia is “about to host China’s first naval facilities in the region.” (Cambodia is allegedly hosting a secret Chinese naval base, China’s first such overseas outpost in the region.)

“Hun Sen has to be reprimanded and put in place,” said Kasit Piromya, a prominent retired ambassador and former foreign minister of Thailand. “All along he has been using ASEAN for his own benefit. He has never been a team player. He does not understand that there is a responsibility to the whole.”

“Leadership and courage have been lacking among the ASEAN leaders. Someone has to emerge, otherwise, ASEAN will keep on sinking and becoming more irrelevant,” the veteran diplomat told The China Project.

Ongoing Burmese crisis

Meanwhile, China looms large in ASEAN’s split over the Myanmar crisis.

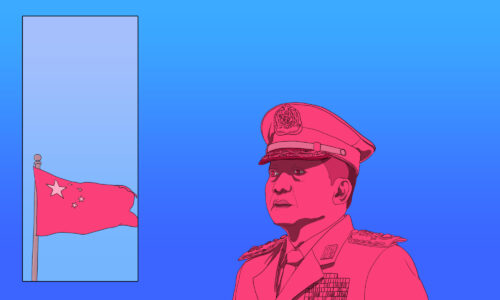

Don Pramudwinai, Thailand’s outgoing foreign minister, held a meeting last month in Thailand’s seaside town Pattaya with the Burmese junta, which has been suspended from attending the bloc’s top summits after Senior General Min Aung Hlaing failed to halt the violent crackdown he promised two years ago. The meeting was attended by China and India but boycotted by some Southeast Asian countries. Don later visited Myanmar and claimed to have met Aung San Suu Kyi.

Myanmar’s National Unity Government (NUG), a revolutionary government set up by deposed lawmakers, wasn’t impressed. “There were only two people at the meeting,” NUG Foreign Minister Zin Mar Aung told VOA. “That is why we are skeptical that the Thai foreign minister or the junta would accurately convey messages from her that don’t fit their agenda.”

“China didn’t go to the Jakarta meeting held by Indonesia but attended the controversial meeting by Don Pramudwinai in Pattaya with the Burmese junta,” a Southeast Asian senior government official told The China Project. “This signals Beijing’s pronounced support for Don’s sidelining of ASEAN and embrace of Min Aung Hlaing.”

“Through Cambodia’s veto of ASEAN’s original naval drills proposal and by expanding its clout in crisis-torn Myanmar, China is seeking to counteract U.S. influence in the Asia Pacific,” the official said. Within ASEAN, Laos, Cambodia, and the Burmese junta are more aligned with China than the U.S., they added.

Myanmar’s pariah junta is pushing ahead with a proposed China-backed deep-sea port on its west coast, which will reduce Beijing’s reliance on the Strait of Malacca by connecting Yunnan Province to the Indian Ocean.

“Look at Laos and the importance of Chinese infrastructure investments. I don’t see that much of a leadership [from the U.S.] in pushing for trade and investments, or forging a stronger alliance among democracies in the region,” the official said.

Waiting for Thailand

Many eyes are watching how Thailand’s impending political crisis unfolds. Pita Limjaroenrat, the leader of the Move Forward Party, the biggest party after Thailand’s May general elections, has expressed support for a “rules-based” world order and to work closely with the U.S. on the turmoil in neighboring Myanmar. But Thailand’s China-leaning conservative establishment has blocked Pita from taking power, paving the way for a showdown.

China is known to harbor resentment against Move Forward because of its progressive credentials. The party’s previous iteration, as the Future Forward Party, also drew the ire of the Chinese embassy in Bangkok. (Move Forward’s star politician, Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, publicly backed Taiwan’s sovereignty last year and is seen as much more willing to work with democracies.)

Ex-Thai foreign minister Kasit hopes that the new Thailand government can reset its foreign policy direction and play a leading role in ASEAN.

The Myanmar crisis, Mekong Basin management, Thai-U.S. relations, and increasing Chinese influence in Thai society and unfair trade practices should be among the top priorities of the new foreign minister, Kasit said.

It won’t be easy.

“With its consensus-based decision making, corruptibility of its leaders, and natural schisms in a host of issues, including the South China Sea, the Mekong, and Myanmar, ASEAN is highly susceptible to foreign interference, and no one is better at exploiting those wedges than China,” Zachary Abuza, a professor of strategy security at the U.S. National War College in Washington, told The China Project.

Many member states are “at the very least fearful of losing Chinese trade, investment, and development loans,” Abuza said.