Political turmoil, separatist violence threaten China’s investments in Pakistan

China’s Vice Premier He Lifeng is in Pakistan talking up cooperation. But Pakistan’s fragile government in Islamabad also has to deal with local resentments at Beijing’s massive infrastructure projects, and its own complicated relationship with Washington.

July marks a decade of cooperation in the $62 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Abbreviated to CPEC, it is a vast infrastructure development scheme, and a key spoke in Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Chinese Vice Premier Hé Lìfēng 何立峰 is in Pakistan this week to celebrate, bearing a letter of congratulations from Xí Jìnpíng 习近平.

Today, in the capital, Islamabad, He called for “an upgrading of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) to promote a closer China-Pakistan community.” Pakistani Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif responded in a speech expressing his appreciation “to President Xi for attaching great importance to Pakistan-China ties and CPEC.”

But CPEC is delayed by political turmoil in Islamabad and separatist violence in the region where its big projects lie.

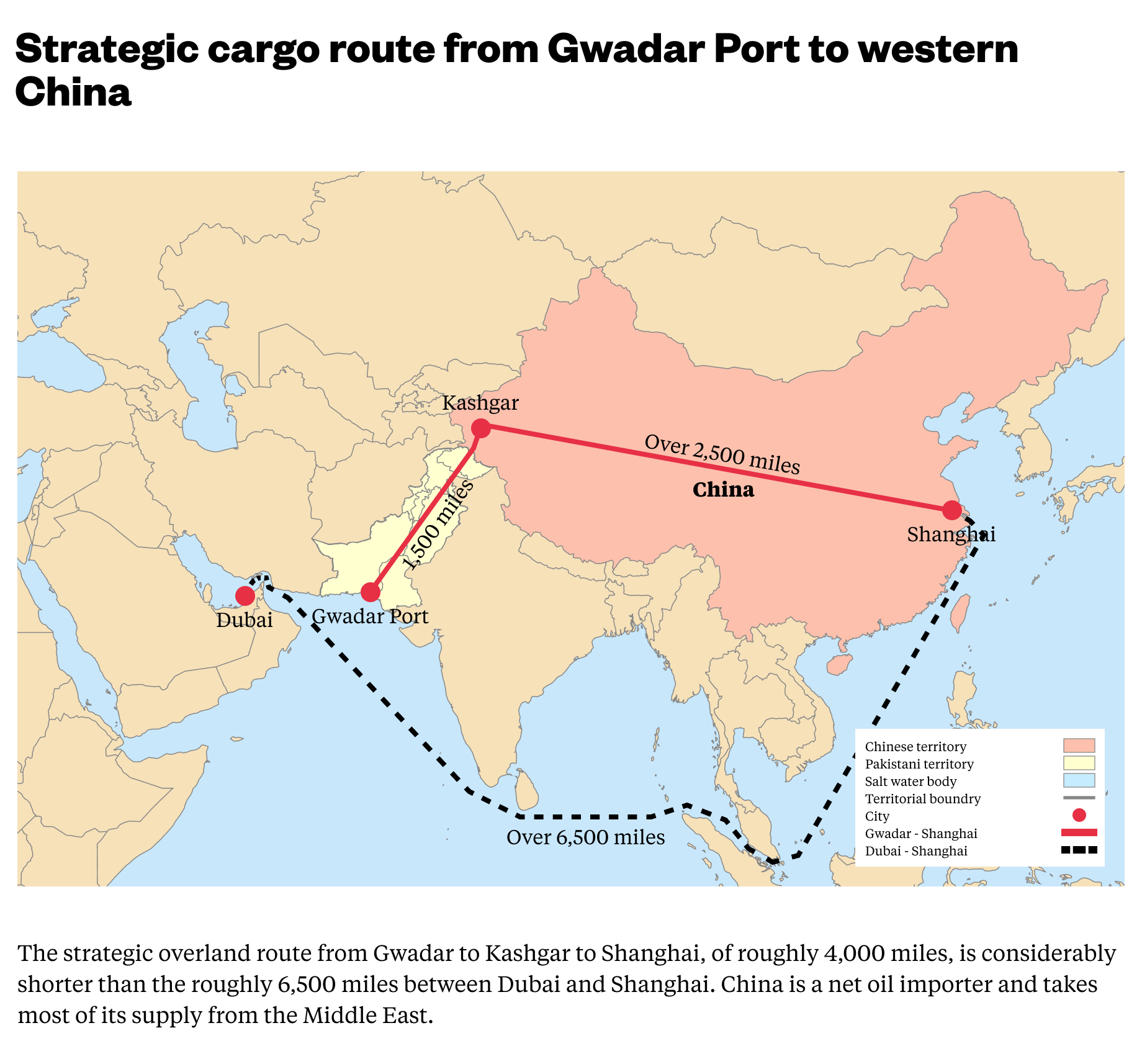

CPEC has seen China’s money — and often its laborers — build out Pakistan’s transportation networks, energy infrastructure, and special economic zones as the start of a long-term plan to link northwestern China’s resource-rich Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region with the port of Gwadar on Pakistan’s southwest coast.

Chinese and Pakistani officials have dubbed CPEC a game changer that will transform the fate of the entire region. Success would enable Middle Eastern oil to flow to China overland by avoiding sea passage through the Malacca Strait, and unlock an exit for oil and gas from landlocked Xinjiang via export terminals at Gwadar, at the head of the Gulf of Oman. In the 2,700-kilometer corridor between the two, Chinese money has upgraded and expanded roads and is set to build new railways, mostly in Balochistan, bordering Afghanistan and Iran, where separatists unhappy with rule by Islamabad increasingly target Chinese workers.

Though first conceived in 2013, CPEC wasn’t announced until 2015, when Xi Jinping, newly risen to General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, visited Pakistan’s then prime minister Nawaz Sharif in Islamabad. The scheme’s start, and Xi’s visit, were delayed by anti-Sharif protests led by cricket superstar turned populist politician Imran Khan.

CPEC projects slowed down under Imran Khan

Less than two years after Xi met Sharif, before many of the 51 initial CPEC projects they had agreed on broke ground, the revolving door to the office of the prime minister of Pakistan started to spin, raising China’s concerns about their massive investments. Over the next five years, Pakistan’s voters went through four more prime ministers.

Imran Khan’s rise to power in August 2018 agonized China as he and his minister for commerce, industry, and investment suggested that all CPEC projects be suspended for renegotiation.

Then, in 2020, two years into Khan’s term in office, COVID’s arrival practically shut off trade, pushing Pakistan’s finances further downward under the weight of deep debt and skyrocketing inflation.

“CPEC projects in Pakistan slowed down, which contributed to China’s disappointment in Pakistan under Imran Khan’s rule,” Muhammad Aamir Rana, the director of the Pak Institute for Peace Studies, told The China Project.

Each time Pakistan changed prime ministers, vested interests supporting the incoming political party reassessed their relationship to China. Even if Beijing’s money was intended to help bring Pakistan back from the brink of financial collapse — with infrastructure, jobs, and the extraction of salable resources — CPEC instead helped plunge Pakistan into a stalemate.

“All political parties, especially the mainstream political parties, pursue their own vested interests, rather than pursuing the public interests,” Jalal Khan, an independent political analyst with no relation to the former prime minister, told The China Project from Quetta.

When, in April 2022, voters replaced Prime Minister Khan with Nawaz Sharif’s younger brother, Shehbaz Sharif, Khan blamed his own anti-American rhetoric for his loss and analysts began to compare Pakistan with Sri Lanka, suggesting that it would be the next South Asian nation to default on its debt.

The long view on CPEC

In June 2023, sensing its investments in Pakistan were under increased threat, China granted a $1 billion bridge loan to Islamabad to help Pakistan avoid a default. Soon after, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, who is up for reelection in October and running, once again, against Imran Khan, secured $3 billion in loans from the International Monetary Fund in Washington, D.C.

Pakistan’s politicians and political parties are neither pro-Chinese nor pro-American, the political analyst Jalal Khan said. But, according to Kaiser Bengali, economist and former member of the Policy Reform Unit of Balochistan’s government, Islamabad’s scrambling for loans from the IMF, was a distraction from Chinese-funded CPEC projects already in the works.

Nonetheless, as the COVID lockdown abated and business returned to normal, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif had reason for cautious optimism.

“Small businesses from China have started pouring in,” Rana of the Pak Institute for Peace Studies said on the phone from Islamabad. “If big CPEC initiatives are stalled but small Chinese business is rising again, that means confidence is beginning to restore between the two countries.”

The younger Sharif would be wise to heed his older brother’s experience with their opponent Imran Khan, who once again is agitating to rally against the sitting government, perpetuating infighting that could paralyze progress.

“Among other reasons, this [infighting] is why Pakistan is in the grip of an acute economic crisis, let alone working on the CPEC projects at the same pace as they started back in 2015,” Rana said.

But China and Pakistan appear to be taking the long-view on CPEC, according to Yun Sun, Director of the China Program at the Stimson Center in Washington, D.C.

“Its impact and effect should not be evaluated by the near-term math,” Sun told the China Project. “CPEC boosts the mutual dependence between China and Pakistan, and offers practical benefits, especially infrastructure projects to local populations, which also boosts the Chinese connectivity and trade routes through Pakistan.”

In 2022, speaking at a seminar on U.S.-Pakistan relations, Sun said she had seen Chinese government analyses urging the U.S. to not “bad-mouth” Pakistan-China ties and to mind its own business, leaving Islamabad and Beijing to negotiate without interference from Washington.

IMF vs. Beijing?

Grateful for the bridge loan from Beijing, Islamabad cannot turn its back on Washington and the IMF, whose financial support carries with it demands for transparency around CPEC in order to build a better picture of Pakistan’s future foreign exchange requirements for servicing its debts.

“Entering a balancing act between the U.S. and China, Pakistan’s engagement with China and CPEC projects got affected,” Safdar Hussain, an independent researcher based in Islamabad, said. “Our trade is with the West and the U.S. We are dependent on the IMF and other donor organizations. Without their support, Pakistan’s economy could not survive.”

To reassure Beijing and reinforce his own personal inclination toward Chinese investment, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif met Xi in September 2022, soon after he took office. The two leaders met in neighboring Uzbekistan and released statements to the press about close relations, friendship, and the importance of CPEC. Xi also stressed hopes that Sharif would guarantee security for Chinese workers and institutions in Pakistan as well as the lawful rights and interests of Chinese businesses.

Michael Kugelman, the Director of the South Asia Institute at the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C., told The China Project that Imran Khan, despite his long list of grievances against U.S. policy in the region, would likely want to have it both ways and embrace the U.S.-backed IMF as well as Chinese investment through the CPEC agreements.

“If Khan returned to power, he would presumably recognize the urgency of Pakistan’s economic stress and understand the need to ease that stress through engaging with both Beijing and Washington,” Kugelman said.

While Washington may not love the CPEC and China’s influence in Pakistan, China has good reason to back the IMF’s loans there, Kugelman said.

“If the IMF plan is properly implemented by Islamabad, it can bring the measure of macroeconomic stability to Pakistan that Beijing requires to get CPEC and its other investments in Pakistan back on track,” he said.

The protesters and militants of Balochistan don’t like CPEC

Sparsely populated, Balochistan is Pakistan’s largest province and home to most CPEC investments. Well before CPEC, China assisted Pakistan in 2002 with the launch of the $248 million Gwadar port project under then-President General Pervez Musharraf, who ruled from 1999-2008.

Once Musharraf was gone and CPEC was on the books, the development of the ancient fishing settlement of Gwadar into a high-tech, deep sea port quickly grew in significance. Soon it was considered the epicenter of the CPEC and is high on a list of global ports where China’s navy is thought to be considering establishing its next overseas base.

Khudad Wajo, a leader among Gwadar fishermen, said that Gwadar “used to be the best fishing point.”

“Besides fish, the fishermen used to catch lobsters, prawn, and shrimp all the year. But after the Chinese development of the port, we are deprived,” Wajo told The China Project.

China’s rise in investment in the port added fuel to a Baloch insurgency that disrupted the CPEC’s progress. Baloch separatists’ fight, often targeting Chinese projects and workers.

At the end of 2021, protests elsewhere in Balochistan coincided with a rise in security threats in the vacuum left behind as U.S. forces decamped from bordering Afghanistan in May. Soon, Gwadar’s main road, Marina Drive, was overrun by supporters of Haq-Do-Tehreek, a Baloch rights advocacy organization.

“Our first protest ended in 32 days, after the provincial government ensured to meet our all demands,” the Maulana Hidyat-ur-Rehman, the Muslim teacher leading Haq-Do-Tehreek, said over the phone from Gwadar after being released from jail on bail.

During the protests, the Maulana warned the Gwadar government to close down the port and the East Bay Expressway leading to it, both projects at the epicenter of China’s investment in the CPEC.

Nasir Rahim Sohrabi, a local social activist, told The China Project, that Gwadar has grown more tense since 2021.

“In the wake of CPEC, instead of dwindling, local Baloch issues, such as health, water, education, among other things, have further increased. That is why Gwadar is tense,” Sohrabi said.

Lǐ Bìjiàn 李碧建, China’s former Consul General in Karachi, told The China Project that he and his superiors met the Maulana Hidyat, who assured him that the local Baloch protests in Gwadar had nothing to do with the CPEC. But after the government failed to meet locals’ demands, they took to the streets again in protest in 2022, blocking traffic to and from the port for two months, occupying the East Bay Expressway, the $168 million CPEC project inaugurated by Chinese officials and Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif.

Eventually, on the night of December 26, 2022, Pakistan authorities cracked down and ended the protests by force, arresting over 100 people.

“I had to go into hiding, fearing for my life,” said the Maulana Hidyat, who still holds small gatherings to address Gwadar locals’ concerns.

CPEC progress does not appear to be helping locals, the Maulana Hidyat said. On the contrary, he said, CPEC’s presence translated into a restriction of movement in his home region.

“Instead of CPEC, I see checkposts in Gwadar and elsewhere in Balochistan in the name of CPEC,” the Maulana said.

Longtime unrest

When weighing the benefits of China’s investments in Balochistan, many locals are left with the impression that no Baloch can benefit.

“The local people’s lands have been grabbed by the real estate tycoons in Gwadar in the wake of CPEC developments,” Asim Sajjad Akhtar, a workers’ rights advocate, said.

For workers concerned that CPEC has grown roots, there’s little end in sight as older Chinese projects are folded into CPEC’s portfolio and given new life.

For instance, Baloch locals complain that they have little to show for the vast Saindak Project. In the far west of Pakistan, near the border with Iran, in Balochistan’s Chaghi district, the Chinese state-owned enterprise China Metallurgical Group Corporation (MCC, 中国冶金科工集团有限公司), has mined copper and gold at Saindak for 20 years. Saindak is now called part of CPEC.

Chaghi district local Ramazan Baloch earned $80 a month driving a dump truck on and off the Saindak site. He told The China Project that he was fired without explanation after sustaining an injury on the job, landing him in a hospital in Quetta, the provincial capital.

Balochistan’s people have staged five insurgencies against Islamabad since Pakistan’s independence from Britain in 1947. The largest was the latest, begun in early 2000, and with each wave of Baloch discontent, attacks rose against Chinese workers and projects invited into the region by Islamabad.

Long before CPEC, Baloch insurgents carried out attacks against Chinese. For instance, in May 2004, militants killed three engineers working at Gwadar.

“After the announcement of CPEC, the situation has gone from bad to worse,” said Rana of the Pak Institute for Peace Studies.

Since 2018, the Majeed Brigade, a suicide squad within the Baloch Liberation Army, has carried out six organized attacks against Chinese installations and nationals. The first female Baloch suicide bomber, a 31-year-old mother of two, exploded four victims, including three Chinese who taught in Karachi at the Conficius Institute, a Beijing-backed soft-power initiative designed to spread the word of the CCP.

Beijing soon pushed to have the Majeed Brigade labeled terrorists by the United Nations Security Council. Yet the violence, which spread beyond Balochistan, continued and raised further alarms in China: in July 2021, nine Chinese engineers were killed in a suicide bombing of the bus they rode to work on the Dasu Dam, in the Kohistan District of northeast Pakistan’s of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province; and in April, 2023, also in Dasu, a Chinese man was arrested for blasphemy.

“Many in China see the emergence of extremism as a threat to the CPEC-related projects,” said Rana of the Pak Institute for Peace Studies.

CPEC after the polls

Imran Khan is contesting the reelection of current Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif in a general election that will be held by October 2023. Its outcome could determine the future success or continued delay of the CPEC projects.

Though China’s direct investment in Pakistan in the name of CPEC is so far up to $25 billion of the projected $62 billion total, all are wondering how whoever rules Pakistan next will get along with Beijing.

“CPEC projects that have been slowed down are being revived,” Muhammad Asif told The China Project. “The general elections and the new government after the election will be deciding the fate of CPEC.”

If the October election is free, fair, and transparent, popularity could restore Imran Khan to office. Now, some of the same analysts who said the 2018 polls that brought Khan to power were rigged suggest that the same sort of corruption could, this time, rig the polls to keep him away from power.

The Sharif government in Islamabad accuses Khan of stopping CPEC projects and making Beijing unhappy during his tenure, a charge Khan’s party, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, flatly denies.

“Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf is committed to taking CPEC forward, ” Shah Mehmood Qureshi, Khan’s aide, said.

The Stimson Center’s Sun said that it is natural that sources of economic support should “fluctuate, recalibrate, and recharge, sometimes reorient.”

“For a country as complex as Pakistan, it would be unrealistic to expect one solution to fix all,” she said. “That kind of solution simply does not exist. The fair question is whether the Pakistani economy could have done better without CPEC for the past decade or so. And I don’t think the answer is so straightforward.”