Below is a complete transcript of the Sinica Podcast with Lyle Goldstein.

Kaiser Kuo: I’m Kaiser Kuo, coming to you from Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

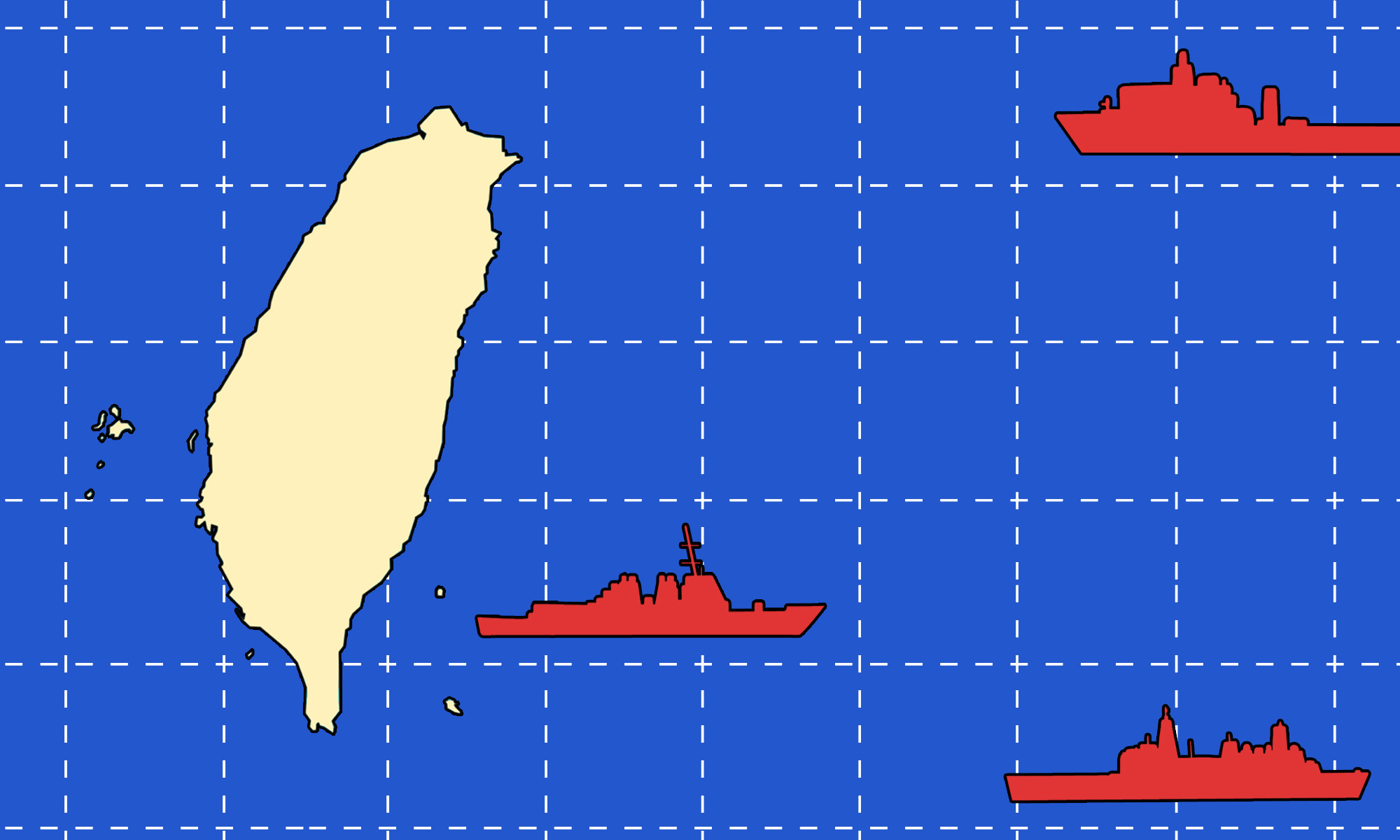

What would happen if China launched a full-scale amphibious assault against Taiwan? This is a question that has preoccupied American war planners, and presumably their counterparts in Beijing and Taipei and Tokyo, and in other capitals, really since the KMT’s retrenchment on the island in 1949. The question has, of course, gained new currency in recent years, whether you think the likelihood of such a scenario has markedly increased or not. So now, how do war planners answer or attempt to answer that question? Well, by staging wargaming exercises. Today, we are going to look at one such exercise, one that stands out, because unlike the vast majority, which are conducted by war colleges or in Annapolis or within the Pentagon, and are classified, for the most part, this one is, in its methods, its assumption, its execution, and its results, public.

They were all made public, and I think that’s to its great credit. Titled The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan, it took place in 2022 and was published in January 2023. The wargame was conducted under the auspices of CSIS, the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and was put together by Mark F. Cancian, his son, Matthew Cancian, and Eric Heginbotham. The latter two were the designers of the wargames. It assumed an amphibious assault, and in the base scenario, direct American military participation in defense of Taiwan. We’ll talk about other assumptions of the game as well. It ran through two dozen iterations with different tweaks to variables. As we’ll see, it’s quite extensive in its scope and a very interesting thing.

Now, there are folks I really respect who tend to be dismissive of such exercises. One very good friend has spoken of grown-ass men going pew, pew, pew with little ships and rolling dice like in Dungeons and Dragons. I confess, I’ve leaned that way. I may still lean that way. But whether you see wargames as basically only a little bit above the level of Milton Bradley — “Aww, you sunk my battleship!” — or you see them as really valid, valuable, and instructive approximations of likely outcomes, we need to look at what they’re all about, and most importantly, what they purport to tell us.

With me to talk about all the pros and cons of wargames, and this one in particular, is Lyle Goldstein, the director for Asia Engagement at Defense Priorities, and a visiting professor at Brown University. Lyle has been on the program twice before — once to talk about his really excellent book Meeting China Halfway, which I really wish more people in Washington had read and internalized back when it was published, and more recently to talk about North Korea. Lyle was formerly a professor at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. Lyle Goldstein, welcome back to Sinica. Great to see you.

Lyle Goldstein: Hi there, Kaiser. Hi, everyone. So glad to be back on.

Kaiser: I’m glad you could make the time to join us. Lyle, you have told me that in your many years, I think it’s two decades at the Naval War College, you didn’t actually participate much in either planning or gaming out the many wargames that are staged there. They’re classified anyway so I wouldn’t ask you to say anything specific about those games, but maybe you could give the listeners a sense for just how important they are at the War College or in other institutes affiliated with the DoD. Perhaps you could talk a little bit about the history of wargaming. I mean, I know for instance, that War Plan Orange, which was the U.S. plan for a war against the Japanese Empire, developed long before Pearl Harbor, actually seems to have grown out of wargaming exercises like these, no?

Lyle: That’s right, Kaiser. I want to say upfront, I was not in the wargaming department, and honestly, I tried to stay out of those games. I was more or less a scholar, a China expert there, leading the China Institute for a while, and really trying to organize our China research. Occasionally, some wargamers would come and ask me questions, things like that, and I would give lectures occasionally to them over the years. But I would state that within how the Pentagon planning process works and the Navy planning process, I think wargames are incredibly important. Going around from my 20 years at Naval War College, I can say that the gaming effort there is not only, you know massive, but it is also treated as sort of the crown jewels of the institution.

I think that goes well beyond Naval War College to the other places where this is done. Part of that is the storied history of War Plan Orange, which is a fascinating story, probably with some lessons for us today. But the United States started wargaming against Japan in 1919 if you can believe it. We were allies with Japan in World War I, and then right turned around and started preparing for war. So, I guess that tells you how things work, what’s changed. Anyway, by 1924, this was described as War Plan Orange, and took on a more official status. But the interesting thing I learned about it is that in the 1930s, the plans were majorly readjusted to take account of the fact that Japan’s Navy was really increasing at a very rapid pace.

This had some major effects on U.S. planning. Originally, I think the plan was to send the fleet over, save the Philippines and give Japan a mighty bruising in the very early stage of the war, but that was all carefully examined, decided not to be realistic, and came up with a much more realistic policy, which we pursued successfully in the war, which was this kind of rather cautious island-hopping strategy, which did not try to get out ahead of ourselves. So, it was quite successful. But I dare say that there are some similarities in that caution that the war planning process imbued our decision makers. I think it’s highly applicable today. We’ll get to that.

Kaiser: Yeah. Absolutely, we will. So, let’s talk more specifically. I mean, we could go on a lot about history. I think that’s fascinating and I’d love to read up more about that. But given your knowledge of wargames, even though you were distant from them at the Naval War College, is your sense that this one differed significantly from the others you’ve seen run? After all, those are all classified. We don’t know the details of how they’re run. I don’t really know whether the Cancians or Mr. Heginbotham had direct exposure to DoD or any of the war college games themselves. But were they significantly different?

Lyle: Not to my knowledge. One can imagine in classified games, there’s more fidelity, more access to higher classifications of intelligence, things like that. But no, as I understand it, the approach is pretty similar. And now, there’s this quite revealing passage in this, first, I’ll call it the first battle report from the CSIS game where they talk about these classified games, and they say, interestingly, that some of this has leaked out into the press. Traditionally, the results have been very high losses and very pessimistic outcomes. That’s what they say. And then they’re quite dismissive, I think, of that, for whatever that’s worth.

There was quite a famous random analyst, I believe he was an Assistant Secretary of Defense, David Ochmanek, I believe. He had said something to the effect of we do this over and over, and the U.S. keeps getting its ass handed to it by the Chinese, which I remember when I first read that, I sort of thought, wow, this is interesting that this is coming into the public realm, to say the least. But again, we don’t know what’s in those games, and we don’t really know, with any fidelity, the results. That’s all behind the black curtain as it were.

Kaiser: Lyle, you’ve said that these are incredibly important to the Naval War College and to the DoD. I know it’s a really broad question, but what is the value of wargaming?

Lyle: Well, I do think it’s extremely valuable. Somebody I admire very much once said that you can’t prevent a tragedy unless you can envision it. Why? Because to prevent it, we have to fully understand the tragedy, if you will. It’s an uncomfortable topic. The idea that we can sit around a table and talk about tens of thousands of people getting killed. I mean, in a way, it’s an awful endeavor to undertake. But to my estimate, even though it’s rather a dark subject, it’s critically important because it allows us to see that tragedy, and therefore to think really hard about how it can be prevented. I would say, of course, that U.S. national security policy and defense policy has a lot of problems. And one of them has been a kind of failure to anticipate certain issues.

Whether it’s the Pentagon Papers or the Afghanistan papers, we’ve seen this again and again, so it’s a related problem, but can we use all the tools at our disposal to look through the crystal ball and see what might happen? I think this has to be done with a lot of modesty, right? Warfare is inherently complex, fog, friction, there are so many unknowns. I mean, the number of factors in play, I don’t think we could ever develop a good algorithm. Some would argue that even the attempt here is kind of, how to put it, it’s immodest. It suggests we could predict. I do think that maybe one of the cautions coming out of this is just that we need a very high level of modesty here.

Kaiser: I completely agree. This isn’t the first Taiwan invasion scenario wargame that has been held, just the first large-scale publicly available one I believe. How significant is it that this has been released publicly?

Lyle: I think it’s incredibly significant. I track the whole literature across the board on China-military scenarios, but the Taiwan scenario is sort of the scenario par excellence, that is, it is clearly the most dangerous one I would say in all respects. Following the literature, I can say I’ve seen some attempts to get this close, but I’ve never seen this kind of fidelity. I do want to strongly commend it to people and congratulate the authors on their extraordinary work here. That’s one reason I wanted to bring this to the attention of Sinica listeners, yourself included obviously. The idea was to start a debate. But of course, that debate hinges on people reading it closely and not just reading the takeaways or something like that, but really getting into the fine print.

I think that’s absolutely necessary. Again, kudos to the authors for putting it out there. Obviously, it was done with all unclassified sources, which is not easy. By doing so, I think they have taken our understanding several levels further. So I really urge all people interested in U.S.-China relations, and in particular in the defense aspects, which, obviously, there’s so much more to the U.S.-China relations. I’m a good Sinica listener, so I know that, and I’m so glad that Sinica is here to remind us frequently that let’s focus on so many other important areas of this relationship. But this one is absolutely very important as you know, Kaiser, and thanks for making time for it, but I really urge people to look at it. Set some time aside, read it carefully. This is so important to the future of our planet.

Kaiser: We will obviously have a link to the report, and although I’m not acquainted with its authors, if they happen to be listening or if they catch wind of this, I would love to speak to one or all of them after this show.

Lyle: I would be listening closely to that, for sure.

Kaiser: Let’s talk a little bit about how wargames like this one are actually set up. Can you describe the physical setup, the game board as it were, and the markers, the dice, and the role of computers in generating contingency and things like that? I’m really curious about what this looks like physically.

Lyle: I hesitate here to make too many comments because I don’t think this was discussed very much in the report that’s available. There were a couple of pictures of maybe the game board and some of the parameters. You have to understand that any, I don’t want to speak for the authors, but I think they would readily admit that any game of this kind is, by definition, a vast simplification of numerous human interactions between humans and machines and technology. Therefore, within the game, you make these difficult calls about this level of simplification. And that has to do with how big the hex is. If anybody has played wargames out there, you know that the actual size and lay down of the parameters of the spaces on the map, that influences deeply how the pieces are able to move around the board and so forth.

I think there’s some of that. I imagine a lot of that is done by computers, certainly at Naval War College it was, but these aggregations of force, in a way I think that is, and the authors themselves, I think, say in the report that that’s, in a way, the hardest. For example, how can you account for morale? So many intangibles. But also they say quite clearly, and here I think is one of the main points of this whole exercise that is we have never seen, other than what we’re seeing in Ukraine, we have never seen high-intensity warfare, certainly not in the naval and air realm, of the kind that would occur in such a Taiwan scenario — never seen that. Perhaps the last time we did see it, frankly, was 1945. That’s an awful long time ago. Another mentor of mine used to say, military operations, as we conceive of them, are like asking a surgeon to operate every 40 years or so.

Kaiser: Wow.

Lyle: Can you imagine? Think about that. Surgeons are trained day to day, and they have the most up-to-date techniques and technologies and practices. But on the military side, the amount of data you have, what are we talking about? We’re talking about learning from the Falklands War? Yeah, you bet. There’s a huge amount of Chinese literature, by the way, Chinese military literature study of the Falklands War. Why? Because that is the last high-intensity air enabled combat that the world has seen.

Kaiser: I also think about the role of contingency. You mentioned morale and the other intangibles, but even something as simple as weather, I mean, in history, we can think of a couple of great examples. The two, in fact, Mongol invasions of Japan that were scuttled, that were completely ruined because of weather, the Kamikaze, right? The divine wind. Then, of course, the Spanish Armada in 1588, also, just because of weather, it was completely wrecked. Is this something you can just roll dice for, or is this maybe so understood now? Have our forecasting capabilities reached a point where weather just can be assumed away as a variable?

Lyle: No, I think you raise a good point. Weather, geography, certainly these play a huge role. But it’s also true to say that progress of information science, intelligence gathering, I mean, often we use D-Day as an analogy, and I think quite appropriate, and the authors of this study do frequently allude to the Normandy invasion from 1944, the allied invasion at Normandy. But then think about General Eisenhower, he didn’t have any helicopters. He didn’t have any drones. He didn’t have any overhead satellite intelligence to look at. Just the information environment has changed to an incredible degree. So, while we should absolutely draw on these analogies, try to understand them, that’s one of the difficulties. And again, lots of credit to the authors. They do quite a good job at drawing historical examples. But I do have some differences in where they made some judgments, as we’ll talk about, I think.

Kaiser: Yeah, we will.

Lyle: And by the way, China has quite a vastly improved weather forecasting effort. A lot of it is directed at these massive hurricanes that hit China occasionally, but a lot of it is also dedicated to military applications.

Kaiser: What sorts of assumptions are built into an exercise like this? One would think that you’d have to have a very good idea of each participant’s, not just their capabilities, but also their own orders of battle, right? What they plan to do. I don’t know how well we know China’s or even some of our allies’ orders of battle, and we don’t know what their warfighting assumptions are. Even the basic scenario here, which posits a massive amphibious assault, is that what China would do necessarily? There are all sorts of people who talk about blockades or other things that are short of full amphibious assault. So I don’t know how much we know this with confidence, and I don’t know how one decides what variables to plug in or what assumptions to plug in.

Lyle: Well, you’re right. That’s why this is so vitally important. But it’s important that we read it critically and that we bring fresh eyes, fresh ideas to this, people of all different backgrounds. There are just too many variables. I think the authors, the report would readily concede that they had to pick and choose and make some judgments. They’re bringing a lot of subject matter experts, of course, and many of them are named in the report and very qualified. But I think that people have differences about how they see this. Now, a couple of fine points there. You alluded to the orders of battle. That is really important. One point of caution that I would say is, look, we have a pretty good understanding of what American forces look like, but even there, I think there’s probably a lot of things that are held, capabilities that are not discussed.

Kaiser: Sure.

Lyle: Let’s put it that way, for sure.

Kaiser: Hope so.

Lyle: Right. Hope so. On the other hand, I’m quite confident on the Chinese side, there are a lot of capabilities that aren’t discussed. So, we’re operating almost in this fog, and we’re doing the best we can. Traditionally, people draw on the IISS annual reports on the military balance as a kind of, well, we can all agree this is pretty decent as far as the set of orders of battle. I’m pretty sure that’s where the authors took the orders of battle. But I have long been concerned that we put too much stock in this that we are overconfident. After all, China is an enormous country, not a lot of transparency there, a lot of warehouses, a lot of underground facilities.

I frequently reminded people that we may think this is what China’s military looks like, but we may not truly know. You raise the issue of how the scenario might look very different. I would just make the quick comment that among people who focus on this day-to-day, we tend to think of at least possible options. There is a kind of political pressure campaign, essentially intimidation. China is already in that. Honestly, if we look at earlier in April, there was that giant exercise, and then back in August 2022, during the Pelosi visit, they were shooting missiles over the island and going over the median line and so forth, although that’s continued. So, you could say that’s already going on.

Kaiser: Stepped up from that, though, obviously.

Lyle: Two other steps up from there, of course, are the blockade, which is much discussed, and rightly so. And then the authors of this report sort of lay that aside, say that’s a good topic. It may be more likely than this, but that’s not what we’re looking at. And I can tell you why, in a way, we should also look at this amphibious invasion, not just blockade. But then there’s one interim step there too, which I would call limited attack. That would be a Chinese assault, let’s say, on, well, it could be on the offshore islands, although I kind of doubt that. I do think an attack on the Penghus is possible the way that was in the 17th century. That’s how the Chinese conquered Taiwan through the Penghus. And Penghus are just 25 miles off the western coast. So that would be a huge blow. I think the minuses outweigh the pluses if I’m trying to step into the shoes of a Chinese strategist. But it is an important scenario to consider. And then, of course, the scenario that we’re talking about today generally is this all out amphibious assault.

Kaiser: Each team presumably has humans playing the roles, right? We’re all familiar or at least sort of familiar with the outlines of Red Team-Blue Team exercises that we had running all through the Cold War. But how much ability do the players have to actually deviate from what they understand are the country that it’s playing and its war fighting plans? In other words, how much agency do the players have?

Lyle: It’s a little bit hard to tell. From my little exposure to these kinds of games, I would say that they, frequently, it’s said, don’t fight the game, really try to play within the rules because there’s always that tension, right? What the wargamers are looking for is to yield these creative insights that either red or blue could play, or green. So, there is that possibility. Again, I give a lot of credit to the organizers of this game and the writers of the report that they have tried to allow you almost to sit there with the gamers and kind of appreciate some of their problems. Occasionally, throughout the report, they’ll say, “Well, some players tried to do this.” And they’ll say, “Well, most of our players playing the Chinese side opted to invade from the south.”

They say that. That’s very interesting. I wouldn’t have known that. I thought this was a fascinating insight, and again, I think they’re quite candid about the results of the report, good on them for that, they say, “Well, look, they have assumed a nuclear decision-making.” I think we’ll talk about this a bit. They’d assume nuclear decision-making out. There are no nuclear decisions, nuclear weapons decisions in the game. And yet they said they still found that players tended to be concerned with escalation and to behave accordingly, which is very interesting. Even though they were explicitly told there’s no use of nuclear weapons or decisions about nuclear weapons in this game, they still almost behaved as if they still existed. A lot of candor in the report. That’s an interesting insight.

Kaiser: Last question before we get to the sort of meat of our conversation in which I will really ask you to talk about the pros and the cons, your critiques as well as the praise you have, last question, how are the political decisions of other countries, South Korea, especially Japan, Australia, how are they factored in?

Lyle: I was just studying that part of the report, and it’s particularly fascinating. As far as I can tell, they didn’t try to model all of those. It seemed like they focused on Japan, which is natural to focus on. And one of the, I would say the top four conclusions of their report, is just the all-importance of Japan and in their view Japan’s decisions on this sort of determine the war either way. I have my own thoughts on that.

Kaiser: So, iterations that didn’t include Japanese participation on Taiwan’s side ended in defeat or ended in what? Less optimal outcomes for the blue team, right?

Lyle: I think they looked at several iterations of Japan’s role. One was total neutrality, presumably that takes off the table. American use of Japanese bases. They basically say that’s the end of that. There would be no U.S. intervention in that circumstance. Then they say it’s also possible that Japan will sort of say, “Yes, you can use the bases,” but Japan’s forces will not be active. Then there are gradations of how active Japan’s forces are going up to fully engaged. What’s interesting here is when they talk about South Korea, Philippines, Vietnam, some of these other countries, and I think they were justifiably cautious, basically saying that their expectation is that South Korea would be neutral.

Kaiser: Sure.

Lyle: The Philippines as well, which is an interesting conclusion. Some may disagree with that, but I, myself, think that’s quite realistic.

Kaiser: I want to spend the rest of our time today just looking at the actual wargame, the CSIS wargame. I know you have quite a number of critiques, but you also have many good things to say about it. You’ve said some very favorable things. I want to just start there. What did you find that you liked that was admirable about this exercise?

Lyle: Well, there are several things that I really liked about it. Again, I’m very glad that this report came out and I just can’t say strongly enough how much I recommend it to colleagues that they not just read the text, but that they read the footnotes, and really go through it carefully. Why? Because it is the best fidelity look. It’s the most detailed and thoughtful approach and really tries to look through different options in a reasonably objective way, I’ll say that. Some other things that I really liked about the report is that it’s very candid about the results. I think some of the reporting was pretty accurate, the reports that came out of the press that said, “Wow, the losses potentially here are huge.” We’re talking potentially tens of thousands of Americans, hundreds of U.S. aircraft could be lost, dozens of ships, and even more possibly, we’ll talk about that, some of their very dark scenarios.

Kaiser: Well, I think the entire Air Force and Navy of Taiwan are lost in the way it’s played.

Lyle: That’s right. That right there I think is meant as a message to Taipei. I mean, frankly, quite accurate. From my assessment too. When I saw that, I was surprised because that’s often, let’s say American strategists think that. They may not say that. They’re too polite, and in this case, I think they were right to put the truth before being diplomatic. Why do they do that? Because a lot of people are concerned that Taiwan is spending a lot of money on its Air Force and Navy, especially over the last 10 years, I think they’ve just launched a new ship, and an oiler. Before that, they launched a major amphibious ship. Got to say that these naval ships are completely worthless in the scenario that we’re envisaging here. The candor there is very welcome. They criticize some U.S. programs as well. I will say that again, rather brave, in the Washington milieu today.

Kaiser: It’s not what the Pentagon wants to hear.

Lyle: Right. For example, I think the Air Force will be a little…. I mean, they’ll be happy because the report really seems to put a high value on bombers. But by contrast, they seem to see fighters as not particularly useful, which the Air Force, generally, is run by fighter pilots. By the way, the Navy is often also run by fighter pilots. That’s not going to be a very welcome conclusion. They also are rather tough on the Army and the Marines which have both put forward this concept of using basically HIMARS, which has become famous in Ukraine. By the way, Asia Pacific security experts knew about HIMARS before it went to Ukraine, because for more than a decade, we’ve been talking about how this weapon system might be put on the islands and used to constrain the Chinese Navy. But I’ll tell you that this report is quite dismissive of those capabilities, saying, actually, it doesn’t really make a difference.

Once the initial set of missiles have been shot off, how are you going to keep these little island strongholds supplied? So, they’re rather dismissive of that capability. They don’t think it’s a very important aspect of the campaign.

Kaiser: That falls under the whole, “this is not Ukraine” kind of.

Lyle: That’s another. Again, one of the top results that the report underlines in the introduction and conclusion is that we really need to think differently here. This is not Ukraine, and therefore the idea that you’re going to continue to push in supplies at a high level and continuously supply the island, that’s completely off the table. They’re very clear about that. They’re also extremely clear about very heavy U.S. losses, especially to surface ships. Here, they do not mince words. They say, if you look, especially the fine print there, the losses are massive. They say in most scenarios, I believe they said within the first couple of turns, the U.S. has lost two aircraft carriers.

Kaiser: Oh, Lord.

Lyle: A couple of dozen surface ships. Those are devastating losses. I taught at a Naval War College for years. Many of my students would be on those ships. It’s almost unimaginable. Those are World War II type losses. By the way, many people, including myself, have said that submarines are the key to the whole campaign. They’re more cautious. They say that submarines actually, while important, are not decisive, because they have a small magazine, a magazine is how many munitions you can carry aboard, and the truth is submarines have very limited magazines. Therefore, their firepower is inherently limited. But yeah, I have a lot of good things to say about this study. I have a lot of critiques as well, but I congratulate the authors on their incredible work.

Kaiser: I think a couple of other things that I would note that are important is they do call this the first battle. This isn’t how the entire thing plays out, right? They’re very clear about that, that this is just the first encounter. A turn, you alluded to us losing two aircraft carriers in the first turn, our first two turns. A turn is only, what? 36 hours in this game, I believe. So, 72 hours, it’s just…

Lyle: Yeah. I mean, it’s devastating. These are devastating losses.

Kaiser: One of the other assumptions, you mentioned this, and I think it is good that they built this. It would’ve been unmanageable to do otherwise, perhaps, but I know this may be part of your critique as well, the whole nuclear question. Maybe we can get to that, but just in the plus column, I would note that they do assume that any strike on the mainland elevates the risk of nuclear escalation unacceptably, right? There are no strikes on the Chinese mainland in this scenario.

Lyle: Well, I don’t know if I’d be that emphatic. Throughout, the authors are saying they believe that the best approach to the United States is to go into planning more or less with the idea that they will not conduct strikes and generally will not overfly the mainland either. They talk about escalation and they talk about how players were concerned with that. But there are also several parts of the report where they say, “Well, actually, we may have to, as it were, overrule that, or certainly there’ll be a temptation to do that.” I can give you some examples, but I think, generally, they’re very candid about this, about how they’ve taken nuclear decision-making off the table. And that’s good to be honest about that.

I certainly understand it, but I must say I’m a little disturbed, though, if we get in the mode where we consider it likely that, for one, that there could be a war with China and nuclear weapons wouldn’t be used, but maybe not. Again, the authors are quite candid about this, and I think in the last couple of pages of the report, they say, “Nobody knows what would happen.” And that’s right. I’m afraid it could be substantially worse even. If you read the pages of International Security and whatnot, a lot of articles recently about inadvertent escalation to nuclear war, that means nobody intends for there to be use of nuclear weapons, but somehow it just happens because some radars are knocked out or satellites are knocked out, and that just gets the ball rolling.

But that’s not how I see it. I think you could have advertent escalation that either side is losing and opts to use a nuclear warning shot or limited use to convey that the war needs to end, if you will, escalate to de-escalate that approach. I heard a lot about that in Ukraine. I’m just concerned by the whole idea that we can assume nuclear weapons out. I certainly understand why it has to be done at some level, and you have to try to understand what war looks like without, but then we just don’t know if nuclear weapons would be used or not.

And by the way, China is building up its nuclear forces in a very robust way. I put it to a very senior strategist in Shanghai when I was in China back in April, I said, “Why is China building up its nuclear weapons so rapidly?” He looked at me and said, “We’re preparing for the worst-case scenario in Taiwan.”

Kaiser: Wow.

Lyle: That, to me, really hit hard. I mean, and I have not heard Chinese strategy, that wasn’t the only time I heard something like that when I was in China. I saw a lot of, as it were, flashing signals there. This is very disturbing, and we ought to keep this in the forefront of our mind. I understand why it was done, but I also feel that we absolutely in every circumstance have to remind ourselves. By the way, when this was rolled out on January 9th, it’s a recorded video, I think you can find it on YouTube when this report was rolled out, you could see some disagreement actually among the experts gathered there about the nuclear risks. One of the presenters there, a former general, said, “Well, we just have to call their bluff and not worry about it. And if we have to attack the mainland, so be it.” While other presenters were much more cautious, and I would be on the cautious side there.

I think nuclear escalation is so dangerous that we had better play cautious. I also want to say, with respect to your point on the first battle title, it is a striking title. It is an important title. I think a lot of people, including myself, sort of went into the report without reflecting too much on the title, but here’s my problem with it. At the same time as calling this the first battle, we call it a wargame. Throughout the report, it is referred to as a wargame. Shouldn’t it be called a battle game? We kind of lose sight of that. I’m just saying, psychologically, reading through this whole thing, we treat it as if we’re talking about the war. We’re not talking about the war. If it was a true wargame, it would model the war to its conclusion. It doesn’t. There’s no theory of termination.

A very fine experienced specialist, Lonnie Henley, stood up at that January 9th gathering, and you can see that on YouTube, and said, “Hey, how does this war end? Because you just said how this China’s amphibious invasion is maybe defeated, but you didn’t explain how the war ends.” I think this is a huge problem. What I’m saying is that the costs of this war could be many times greater than what is discussed in the report. In effect, we should, I guess not to nitpick, but we might call this instead of a wargame. It’s a battle game.

Kaiser: Fair enough. I think the fact that they do bring up, though, they remind us periodically through the report that this is about the first battle and that it is not about the war. I mean, I’m not sure what else, what more they could have done to reinforce that point, but I take your point.

Lyle: Well, hold on. You do occasionally see this kind of odd reference. We can talk about what they call sort of the most pessimistic scenario, which they hit somewhere on sort of page 99. So, you have to read well into the report. But in that very dark scenario, at one point they basically say the U.S. losses are huge. And then they say the game was called, but what does that mean? Game was called? I guess it means everybody was tired and depressed. That’s what I’m saying.

Kaiser: Game over, man

Lyle: I guess if you iterate this 24 times, you can’t possibly, and I think somewhere it says in the report that you could have thousands, even millions of variations if you continue to, and they have to make this realistic. But still, you have to keep in mind that a war could be a decade of war. It could be maybe the first war. There could be another war or third war. When we talk about superpowers going to war, as we are here, we better keep that in mind.

Kaiser: At the risk of getting a little bit too much into some of the military nitty-gritty, I do want to ask you about your take on the amphibious assault in general. I think you have a pretty different set of conclusions or assumptions than the authors did. Can you unpack that a little bit?

Lyle: In general, I’m afraid some of their assumptions could be questionable here. I do feel strongly that they underestimate the number of U.S. Navy ships that might be sunk, unfortunately. But you can look at some of their numbers when they talk about the success of anti-ship missiles, and I see things like they’re crediting the Chinese with something like a 3% hit rate — 3%. Well, to me, that would be wildly optimistic. But let me return to this issue of amphibious. What does the Chinese amphibious fleet look like? And why do I think there’s a problem here in the report? Here, they’re very crisp about this. They say, look, the Chinese have about 96 large amphibious ships of various kinds. Those are the main ships of concern. By the way, they include in that RoRo ferries.

Kaiser: Just a quick note, RoRo means roll on, roll off.

Lyle: But they say it comes down to this number 96 and say, if they sink, some good portion of those 60 or 80 of those ships that’s feasible for U.S. forces and that’s the whole invasion. I disagree. I think a lot of Chinese soldiers will get to Taiwan by parachute or by helicopter, and they’re very dismissive of that possibility. But the larger problem is this, Kaiser, China has a massive merchant fleet, a massive coast guard, a massive fishing fleet, and there’s good evidence that all of this will be very strongly engaged in this endeavor. By the way, check out a report by Lonnie Henley. I’ve recommended him before, but he has a report at Naval War College published by Naval War College in May 2022, where he says, this effort to use the merchant fleet, civilian shipping is the backbone of the invasion.

His evidence is very good. He says, it’s not a stopgap. This is not like just trying to fill a hole here, but this is rather their preferred approach. I agree with that. Of course, it’s somewhat deceptive, right? Here, I’m talking about thousands of ships out there. That changes the whole equation. There’s not 96 ships you have to hit. There are thousands.

Kaiser: Reverse Dunkirk.

Lyle: That invalidates this. I think there could be 5,000, there could be even 10,000 ships in a variety of different armadas. There’s just no way you can do targeting for that problem. And they’re willing to take huge casualties. Now, the authors kind of dismissed that possibility by saying actually that this was tried at Gallipoli. Folks, do you know about Gallipoli? This happened a long time ago. They were using rowboats back then. I don’t believe that’s a good use of history there. I think that’s a mistake, a major mistake in the report. We have to conceptualize that this, the armada that China would invade with, is much, much larger.

Kaiser: You also take issue with the emphasis they place on bombers, on long-range bombers as sort of the main weapon in the American air arsenal. What’s your problem with that claim?

Lyle: My analysis generally has tended to focus on submarines. Here, I quite agree with the reports, conclusions on submarines. They say that submarines cannot be decisive here because of, like we talked about, those small magazines. There are other problems with submarines too. Mines we’ve talked about and other, and the reload of the submarine is very difficult as well. The numbers are not adequate.

But for bombers, somehow the authors really alight on bombers as the key capability. I don’t see that. The U.S. bomber force is, first of all, not very large. There are many other problems with this as well. The bombers have to get reasonably close to launch these munitions.

And China’s fighters have a lot of endurance. They have a large combat radius. They can get out pretty far. So this will be, I would say, a hot environment for our fighters. And they will definitely go after the tankers, right? Our bombers can only operate if they’re supported by tankers. The Chinese know that. They will go right after targeting those tankers, and they will target them at a distance. The gamers, in this report, they’re quite dismissive of China’s ability to reach out. I could easily see a submarine getting off of Alaska and hitting our major air force base in Alaska, for example. But the same thing could happen in Hawaii and Guam, of course, will be targeted.

Kaiser: Well, that’s an attack on the mainland, though.

Lyle: Yes, I mean, this is something I think is quite possible. Because they know that they would have to target these bombers, I think they could do so rather successfully. Now, those bombers, you have to think about the munitions they’re shooting. And here, the authors are quite specific, they admit that the number of munitions right now that they expect in 2026 is something around 400, or 50, I believe, of these specialized munitions. By the way, these munitions, they’re called LRASM, are not very long-range anti-ship missiles. These missiles are subsonic. Subsonic missiles can be targeted. They’re coming down rather predictable vectors. The Chinese know that. Chinese have exercised very frequently with like-point defense, basically putting as much metal into the sky as you can and downing some of those.

I don’t think there will be a high effectiveness for these munitions. I think there are plenty of countermeasures, and China will go all out getting its fighter force out there beyond Taiwan to form a shield, which I think will be quite effective. Then there’s the biggest problem, which alludes to the point I just made about the number of targets. If you only have to destroy 90 ships or 80 ships, maybe the bomber force could be decisive, but if the number is more like 800 or 8,000 ships, there’s absolutely no way that this is a drop in the bucket effectively. So I would strongly disagree with the conclusion that the bomber force will be decisive.

Kaiser: Lyle, what did you make of their assumptions about the way that decisions or political decisions are made in the allied capitals in the United States in DC and in Tokyo?

Lyle: I tended to focus more on things I know a lot about, the systems going at each other. That was kind of where I put my focus. But my thoughts on the decision-making calculus, frankly, I was a little bit disturbed by the tone there. Although I suppose the simulation is quite realistic, when we think about sort of truncated decision-making, meaning, Mr. President, you’ve got to make this decision whether we’re in or not, whether our forces can go right into combat or not, when you make those decisions, they seem to suggest very clearly, as part of their findings, that the U.S. and Taiwan are much better off, and to assure a win, you need those decisions made extremely quickly.

To me, it did feel very unrealistic. In fact, I don’t recall any mention in the report of whether the war powers resolution or the constitutional issue of the fact that the Congress… This would be a war, folks. Clearly, the Congress should be involved in my perspective. By the way, that goes for Japan too. At one point, I recall, I went over this the other day, their assessment of Japanese decision-making, they said, “This is fully within the powers of the Prime Minister of Japan to make this decision. So, it all depends on him or her.” Actually, I think that is a vast simplification as I understand Japanese politics, and I believe the courts might play a role in the Japanese case, right? Because there are some complications with the peace constitution.

I don’t doubt that the Japanese legislature would also seek to be involved. This is democracy after all. What I’m saying is, while from a war planners or, if you will, from a military point of view, you always want the decision to be made without delay, but yet, I just don’t think that’s how politics work really. Given what we’ve seen on Ukraine where decisions have evolved, let’s say a lot, and they started out very cautious, especially when we’re talking about two nuclear powers potentially going to war, if we took the Ukraine lesson, we have to say that it’s very unlikely that the U.S. and Japan will both jump in with two feet at that immediate moment.

Kaiser: Lyle, you also take issue, I believe, with this assumption that we would have at least two weeks of sort of unambiguous warning that this was coming. I know you’ve probably read John Culver’s report in the Carnegie Endowment for National Peace, but you think that there wouldn’t necessarily be anything like that kind of a long warning. Can you break that out a little bit for us?

Lyle: I noticed Culver’s essays cited in the CSIS report, and I think most people agree with Culver as it was a well-received piece. I don’t. I take issue with it. I have a lot of respect for him. But here, I think he’s quite off the mark. He argued that we would have months of warning. Now in the report they say, well, the Chinese might be able to orchestrate something more devious or, if you will, more deceptive. So not months, but they think days, 14 days at least. They really think 30 days. And they say 14 days of unambiguous warning. In my view, I think we can expect just a few hours, and maybe not at all. That’s my view. I’m happy to give you my where that assessment comes from. But just in a nutshell, I would say, look, we have a whole history of Chinese pattern of this where they have been very successful at deception.

Sun Tzu said all warfare is deception. Look at Korea, we were completely surprised when they entered the war against India. They were also completely surprised.

Kaiser: But we didn’t have satellites back then, we didn’t have nearly the kind of, even the OSINT that we have now.

Lyle: We had a lot of capability, though. We really owned the air and we had people on the ground in Korea and all that. I don’t think that’s such a good excuse. On the other hand, I think China also has a vast apparatus for creating deception. I spent a lot of time in Chinese ports like Dalian and Qingdao and so forth, and it’s just incredible, the scope of not only the merchant fleet, the fishing fleet, and all these just vast warehouses everywhere. Let me put it also to you this way that when we’re talking about air and missile forces, these are very quickly deployed, and most of the force is already in place.

The same goes for heliborne and airborne forces that again, it’s a matter of hours pushing it forward. Then what I would expect is what I call a rolling start. A rolling start begins with the missile, air drone, heliborne attack. And it’s only then, once that is underway, and there’s substantial fighting on the island, I think tens of thousands of PLA troops on the island brought by parachute or helicopter or special boats, whatever.

Only then is the full call up and things begin to go upward ships. If you look at D-Day, 150,000 troops and all their equipment went aboard in just five days. I actually think the Chinese would be much more efficient than they were on D-Day. Why? Because D-Day was put together in about a year and a half. China’s been planning this for decades and has the most advanced ports in the world. I rather suspect that these ships would be loaded very quickly. Another thing, we could talk about this all day, but another aspect of this here, well, I would say they’ve also normalized this pattern of exercises. Actually just today, there was a piece in The New York Times, it’s August 11th, a piece by Chris Buckley that talked about how these exercises have become so common that Taiwan forces have sort of said, “Well, we’re not going to intercept. It’s too expensive to try to intercept all these.”

So, it’s become rather normal for a large quantity of Chinese ships and planes to be sort of circling the island at any given time. And of course, that can quickly go into the real thing. One final thing I’ll say here is I’ve looked a lot at how China has actually studied Normandy a lot. And by the way, they studied Inchon, and Inchon is almost more interesting. Their conclusion on Inchon, this was MacArthur’s famous invasion in September 1950, where he really turned the tables with a brilliant operation. But they literally said the reason Inchon succeeded is because nobody thought they could do it there, and that’s why it was successful.

So, go with the unexpected. I’m convinced that Chinese strategists fully understand that surprise is the key to the entire operation. They will go all in on surprise. That’s why I almost find it comical when I hear my colleagues saying, “Well, I’m reading the tone of this latest editorial and PLA daily, and it sounds very chill.” Okay? So, I guess they won’t go tomorrow. They’re looking, and they also, there’s an expectation in the game. And here, I don’t agree with this in the CSIS game, they say they expect there will be about a month of crisis or something preceding the attack. I don’t see it that way. I think China is wise to this and knows that to get full surprise, they don’t want to act in the middle of a crisis. They’ll act, essentially, as a bolt from the blue. That’s my expectation. And it’s driven by the military imperative of surprise for amphibious attack.

Kaiser: In an interview that Chas Freeman did, I guess it was more than a year ago, we were talking about Admiral Davidson and the suggestion of 2027, and he said the most likely moment for a Chinese surprise attack would be after November 2024. He thinks that it’s when there’s sort of this moment of where we momentarily are kind of incapacitated, we have a presidency in transition or in the immediate aftermath of January 20th or inauguration day. That’s the danger period.

Lyle: We can think about a variety of danger periods. By the way, Hawaii is going through a terrible crisis right now, right? A lot of distraction in a major base area, I mean, probably not the actual bases, but I’m just saying one can imagine a Chinese leader saying, well, we got these variety of opportunities, what kind of opportunities they are, ranging from something going on in the Pershing Gulf, let’s say, to some massive storm knocking out power on the east coast of the U.S. One can imagine a variety of issues that might play into this decision. I’ll give you an example here again, I mentioned the Sino-Indian War. There’s a reason why not many American strategists are that familiar with it because it happened during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Kaiser: Cuban Missile Crisis, yeah.

Lyle: The U.S. was fully distracted during that, and China knew it, and therefore was able to act very robustly and without any concern. Actually, the Indians did a cable from Nehru to Kennedy, “Please send help now.” The phone was not answered at all because Kennedy was very tied up. So, I could imagine. And I do think there’s a danger with Ukraine. If the Ukraine War continues to escalate and so forth, or continues to go in unexpected directions, China could use that. Clearly, they know that a lot of U.S. effort, say intelligence effort, for example, there’s only finite capabilities to watch closely. A lot of that is now directed at Russia, of course.

Kaiser: You’re going to find yourself quoted by Bridge Colby in a second.

Lyle: I’ve gone around the bend with Bridge. He is very smart, but we disagree on a lot of things.

Kaiser: I’ve had some funny encounters with him as well. So, your overall top-level worry then is that without reading the fine print as it were, policymakers or influential media outlets or personalities, or maybe even key people in the national security establishment are going to come away though with too sanguine a view on what the upshot is, what the casualties would be, what the results would be. That this is ultimately doable. Is that fair?

Lyle: That is kind of the disturbing feeling I get after reading the report carefully. I feel like the authors have ultimately come down and said, “Look, this would be hard, but if we make a few critical decisions, we don’t need to radically expand the defense budget. We just need to invest in these several capabilities.” Like I said, they favor bombers. They want to see a lot more munitions put on these bombers. I’m quite skeptical of some of their recommendations there. Also, I do think that the estimates there, as far as losses, are far too optimistic favoring the United States. That is, unfortunately, although they’re presented as sort of catastrophic losses, hundreds of aircraft, dozens of ships, I’m afraid it could be considerably worse, Kaiser.

That’s my evaluation of their assumptions, looking at some of the numbers that go into their assumptions, and just based on my own research of some of China’s countermeasures.

Kaiser: In a nutshell, if you could summon the National Security Advisor, the Joint Chiefs, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and the President himself, get them to sit down and you give them your take on what comes out of this wargame, what would you say? You get your chance to rewrite the executive summary.

Lyle: Oh, goodness. Well, I think, by all means we should hear what the authors have to say themselves. Again, maybe I’ll refer you to that YouTube presentation they made on January 9th of 2023. My take is that I agree that the war could be devastating, but I think if we take that sober look, which we got from this report, and then inject some additional uncertainty, especially given nuclear risks, but also I would say, have we perhaps underestimated the lethality of some of China’s weapons? I think, unfortunately, that may be the case. Losses could be considerably greater, in my view, than this report says. I think losses could be even double or triple what they project. And I’d like to back that up with some evidence if you’ll permit it.

But given all that, I believe that the United States should be extremely circumspect about this, and by the way, the Japanese as well, and should reflect a little less on what magic capability they can produce to solve this problem. Because after all, that’s our go-to idea. This is a tough situation. What technology can we invent to solve it? That’s how Americans do things. But that didn’t work in Vietnam, it didn’t work in Afghanistan, and it’s not going to work here. This is a bridge too far. That’s my view. We should recognize that and take a much more realistic view. That means having a very robust diplomatic track to help Taiwan preserve its autonomy to keep with strategic ambiguity, maintain the One China policy, and really use diplomacy, which we can talk about that. That’s not really discussed in the CSIS report, but it’s critically important to pursue some sort of reassurance on that count.

From a defense point of view, I think we can make some prudent investments, draw red lines that are realistic for the back, realize that the Pacific is very big and wide, and that Japan and the Philippines are not under grave threat. Taiwan is under grave threat, but our treaty allies are not, and reconsider and play this very cautiously.

Kaiser: Lyle Goldstein, thank you so much for joining me again on Sinica and for sharing your informed views on this wargame and on other subjects. It was just great to have you on again, man.

Lyle: Thank you so much, Kaiser. Really glad to join you.

Kaiser: Let’s move on now to recommendations. But first, a very quick couple of reminders. First, don’t forget that our next China Conference is in New York on November 2nd, the Midtown East area near the UN, a lovely event space. You can get tickets now. It is going to be a fantastic conference. Great speakers like Yasheng Huang and Evan Feigenbaum, lots of folks from government, from major think tanks, from the media world, from academia, and from industry. It’s going to be quite star-studded. Some very deep, very heady panels that we’ve got planned, deep-dive breakout sessions on super important topics, and even a kind of jeopardy like game show that I will be hosting at the end of the day. I will also be taping a live Sinica episode along with Jeremy on the evening of November 1st in New York, the exact location and guest, TBD. So, sign up for that as well if you can. And if you can’t come to the conference, but you still want to support the work that we’re doing, please take a moment and become an Access member of The China Project. You get our Daily Dispatch newsletter, you get early access to Sinica. and much more, all for the cost, three or four cups of coffee a month. All right, on to recommendations. Lyle Goldstein, what do you have for us?

Lyle: Well, thanks, Kaiser. I’m a little reticent here to share my recommendation just because I feel like this has probably been said before. I live in Southern New England here, and I must say the best Chinese museum presentation I’m aware of around here is at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. They have this incredible exhibit. They took an incredible, well, almost a palace, transported it, the entire thing from Anhui Province, and deposited it inside the museum. It makes a stunning courtyard. If you haven’t seen that, you must see it. Having been to Anhui myself and seeing some of these gorgeous villages, this is a very faithful take on it. It really gives just a wonderful view of Chinese aesthetics and the design and philosophy and history.

And of course, all the research surrounding it and how they moved this wonderful piece of architecture over, it’s called Yin Yu Tang. And it’s just stunning. So, please make the time and go see. By the way, I used to parade Naval War College faculty through there so that they would deepen their understanding of how Chinese think about aesthetics and design.

Kaiser: Lyle, that has not been recommended on Sinica before, and it’s a fantastic recommendation. There was no reason at all for you to be reticent about it. It’s great, man. I’m anxious. I want to get up there and check that out.

Lyle: Salem, Massachusetts. Yeah, outside Boston. You can check out the Witch museum too, there.

Kaiser: Yeah, for sure, for sure. All right. I want to recommend something once again. Actually, I’ve recommended I think bits and pieces of this before, I’m not sure I’ve ever recommended the whole thing, but the series, The Story of Civilization by Will Durant with the later volumes, co-written with his wife, Ariel Durant. Growing up, I think every family I knew had a set of these, along with their World Book or Britannicas. I didn’t know many people who actually read them, though. When I was a child, it just never sort of occurred to me, they were so thick and so daunting, and I just never pulled any of them down and really flipped through them. I started doing that in high school.

I read The Age of Faith, which is the fourth volume of 11, just because I was… I think I was writing a paper on the Crusades or something, but then I realized it was just so well written and so interesting, so engaging that I devoured the whole thing. I only revisited them maybe a decade or so ago, and then I actually set a goal of reading all of them. And so, I’ve done that. I listened to most of them. I’ve read some of them in print, but most of them were available, more and more of them became available on Audible as audiobooks. They’re just a delight. They’re just so fun to listen to. I mean, long drives or on flights or whatever, walking the dog or cooking or doing the dishes, or all those mundane things that you do where you can have a pair of earphones in. Well, these days, I listen to audiobooks as I practice archery. I try to practice for an hour or so a day, and I listen to them, but they’re just an absolute joy.

There’s all sorts of really sly, often pretty risqué humor. He’s just very funny. And just as a pro-stylist, Will Durant was just amazing. I recently finished two, I revisited two, just because I was on this sort of Thirty Years’ War kick I talked about a little bit ago, and I decided to sort of read The Reformation and then The Age of Reason Begins, which covers that. It’s actually in that one that Thirty Years’ War is covered, but all the wars of religion and the reigns of Elizabeth and the early stewards and stuff. It’s great stuff. It’s amazing stuff. Last night, just for the hell of it, I just started listening to Our Oriental Heritage, which is the very first one, which I haven’t gotten back to in a long time.

But just the opening essays of that, maybe that’ll be my more focused recommendation, the early chapters of that. There are these real essays on civilization. This was published in 1935, so it reads like it’s dated, and it’s interesting because this is before the second war, but still in the aftermath of the first. There are references to Versailles and things like that. Lots of things that are wrong with audible.com, I know, and I find them problematic as the monopsony that they are. But it just is amazing to me that for one credit, you can actually, 10 bucks or whatever, you can listen to 50-plus hours of this amazing high-quality narration of brilliant historical writing. It’s a miracle. Anyway, that’s my recommendation, Will and Ariel Durant. It just never gets old. I love their stuff so much. Lyle, thank you once again for joining me.

Lyle: Thanks, Kaiser. It’s been a real pleasure talking with you. Let’s do it again soon.

Kaiser: Absolutely. Yeah, sobering stuff too. But I will put a link to the report, and once again, if Mr. Cancian either feel or pair our listening, or if Mr. Heginbotham wants to get in touch, I would be delighted to talk to you more about this wargame and the report.

The Sinica Podcast is powered by The China Project and is a proud part of the Sinica Network. Our show is produced and edited by me, Kaiser Kuo. We would be delighted if you would drop us an email at sinica@thechinaproject.com or just give us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts as this really does help people discover the show. Meanwhile, follow us on Xeeter, as it’s now called, or on Blue Sky, or I think we’re on all of them now, Bluesky and Threads, or on Facebook at @thechinaproj. And be sure to check out all the shows in the Sinica Network. Thanks for listening, and we’ll see you next week. Take care.