In a retro mood: The ethical dilemmas of cutting a deal with Xi Jinping’s China

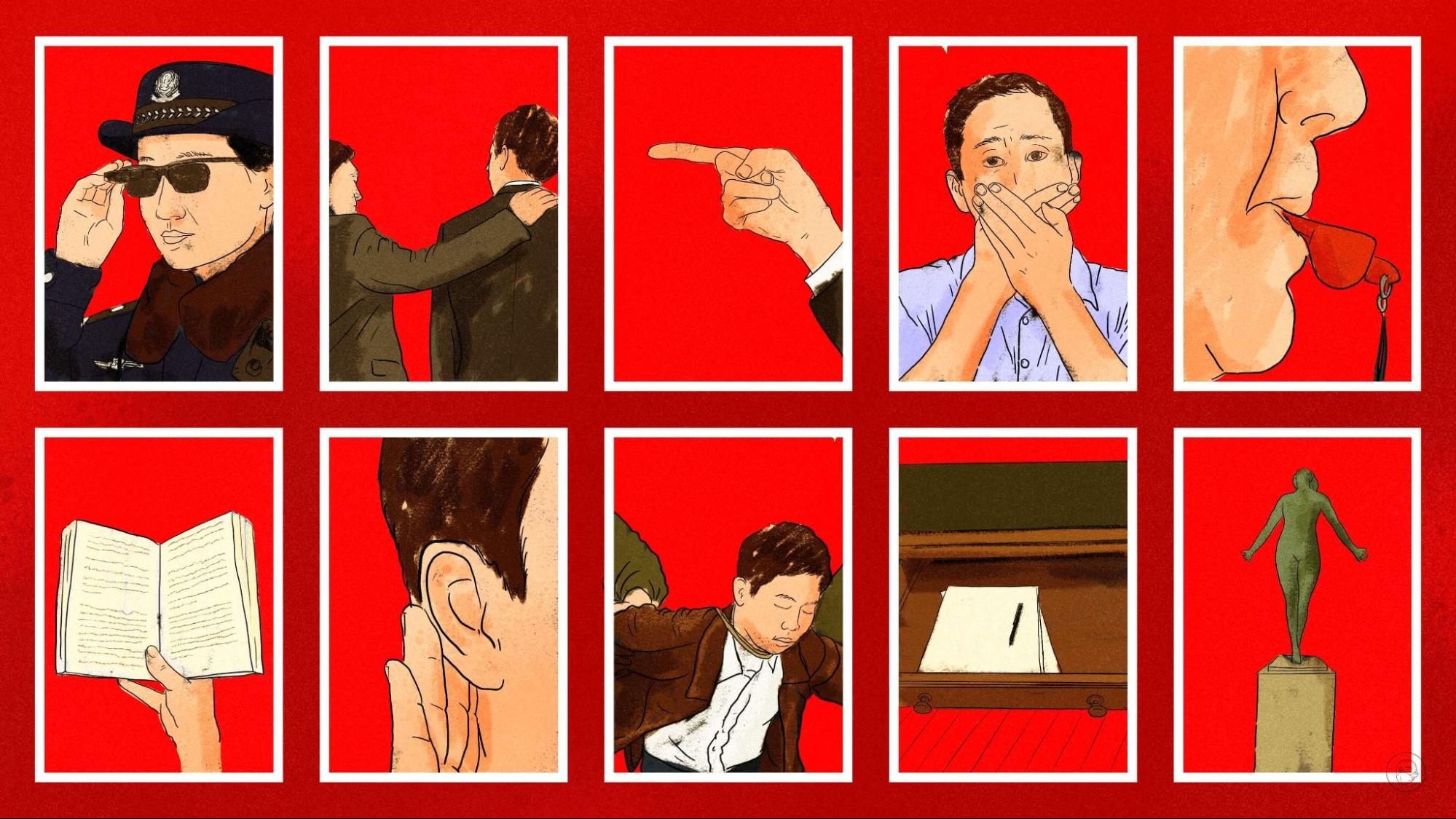

How can scholars, journalists, and others engage with China ethically? The eminent Sinologist Geremie Barmé offers 10 watchwords.

My last trip to China was in March 2017, and this is now my longest absence from the People’s Republic since I first went there to study in October 1974.

On that recent visit, I was a guest of the Shanghai International Literary Festival, the creation of Michelle Garnaut, the Australian restaurateur and cultural entrepreneur whose base was M on the Bund. My session at the festival introduced the audience to China Heritage, a new online site. At the Australian launch in December 2016, I’d given a talk titled Living with Xi Dada’s China — Making Choices and Cutting Deals. In Shanghai, I also focused on Nanking, the theme of the first China Heritage Annual.

In Making Choices and Cutting Deals, I had offered a gathering of mostly younger scholars of China some reflections on half a century of involvement with the Chinese world. I had concluded with a few suggestions on how to cope with the increasingly treacherous intellectual and academic environment of China under Xí Jìnpíng 习近平. I was motivated by the fact that, by 2015, some graduate and postdoctoral scholars I knew had found themselves under increased surveillance during their research trips to China; some were even attracting the attention of the “relevant agencies” in their own countries. There was no doubt that, before long, many other academics working in and on China would confront a similar situation.

Following that trip to Shanghai, and since I had retired from institutional academia, I suggested to former colleagues both in Australia and North America that perhaps it was time for China scholars to reflect on how they would deal with a revanchist People’s Republic, a topic that I previously commented on in “Ugh, here we are,” an interview with The China Project. In particular, I thought it was necessary to revisit the history of how Western academics had engaged with the Soviet Union during the Brezhnev era, and how China specialists had worked in China during the 1970s and 1980s, as well as in the three-year counter-reform of 1989–1992 (elsewhere, I have argued that those years adumbrated the Xi Jinping era).

Since the lifting of COVID-era travel restrictions, and in light of the even more treacherous intellectual and cultural environment of China today, I have yet again encouraged friends in academia to engage in a broader, multi-perspectival discussion about individual and academic ethics and the P.R.C. I believe that such discussions will also be of interest to people working in journalism, government, business, and consulting.

Before offering an updated version of the advice I shared with my audience in December 2016 below, I discuss some personal experiences from nearly a lifetime’s engagement with Chinese people and experience dealing with the Chinese party-state. I hope these thoughts and suggestions can supplement the efforts of those who are already working on navigating a way forward.

The political commissars in Mao’s China perceptively condemned me for what they called my “bourgeois anarchic” attitude. It was an assessment with which my German-Jewish father wryly concurred. Indeed, I’m the first to admit that I’m not the kind of phlegmatic guide to the diplomatic skills so often required in China studies. Nonetheless, I do feel that I have acquired some insights into the moral hazards of China-related scholarship. I also hasten to add that I am not American and, although I have spent long periods working with an independent film group in Boston and pursuing projects in New York and Las Vegas, my personal and professional perspective is not that of an American. Caveat lector!

Under the Party’s ears and eyes

Over the decades, too often have I had the wrong interests, pursued the wrong ideas, befriended the wrong people, and written the wrong things. So it is no surprise that, to a greater or lesser extent, I’ve often been the object of official scrutiny. Surveillance was a feature of my Chinese life from the moment I arrived in Beijing in October 1974 and it wasn’t long before I was made aware of the universal presence of “eyes and ears” (耳目 ěrmù).

One morning, shortly after having settled in to the Foreign Languages Institute, I was brushing my teeth in the collective washroom of our dorm when a gruff voice barked at me over the cement trough that divided the rows of spigots: “You’re sneak-listening to enemy broadcasts!” (偷听敌台! tōutīng dítái!).

The voice belonged to a Worker Peasant Soldier Study Officer (工农兵学员 gōngnóngbīng xuéyuán — Cultural Revolution-era terminology for “student”) who was wearing, even at that darkling hour, a high-collar blue Mao jacket. Steely faced, his tone was both a warning and an accusation. I had no idea what he’d just said. I’d put my small radio — listening to which I hoped would help improve my language comprehension — on the dividing ledge of the trough. The radio was tuned in to a station with a newsreader I could just about believe that I understood. They weren’t declaiming the news in the harsh shotgun staccato, or at the seemingly impossible speed that was blaring out of every loudspeaker in our dorm and around campus. The delivery was nearly dulcet in tone and I presumed that this milder voice must be coming from some local station or even a provincial broadcaster.

“It’s Soviet Revisionist radio!” (苏修广播! sūxiū guǎngbō!), my grim-faced interlocutor spat. That, I understood. But it still took me a moment to work out what was wrong. I was soon enlightened by the political commissar who was in charge of our small contingent of students from Australia and Canada. The incident had been reported and I was now chastised for having threatened the ideological purity of my Chinese classmates by listening to “the enemy,” no matter that I had done so inadvertently.

It was the first lesson I learned in China and it was about the culture of snitching. A more important lesson, however, came with the realization that what I did might negatively affect those around me. My classmate had probably reported me more out of an impulse for self-preservation than as a result of some perceived anti-foreign animus, even though antipathy toward Caucasian foreigners was nearly universal — today’s wolf warriors are pups compared with the generation of former Red Guards and PLA university administrators that I encountered in the 1970s. They had been suckled on metaphorical wolf’s milk (喝狼奶长大 hē lángnǎi zhǎngdà), and it was a far more heady concoction than the watered-down version fed to the big and little pinks of today.

Before long, I realized that the “eyes and ears” were ubiquitous. That was bad enough, but it was the “claws and teeth” (爪牙 zhǎo yá) of the system that we all learned had to be avoided at all costs.

Everywhere there were blaring reminders that vigilance was vital for the security of the fatherland, summed up in the Mao slogan “Be vigilant and defend the motherland” (提高警惕,保卫祖国 tígāo jǐngtì, bǎowèi zǔguó). An early version of “see something, say something,” this was the watchword wherever you went and people acted on it with alarming frequency. With conversations reported, casual encounters with everyday people policed, letters opened, and constant warnings and cautions, it was hard not to be both paranoid and thick-skinned. I later learned that the culture of reporting worked both ways. In her patriotic fervor as a “progressive” overseas Chinese student, Jan Wong — a schoolmate who later had a distinguished career as a Canadian journalist — reported on someone who had expressed a wish to leave China.

Long-term foreign residents were both victims of and participants in the ingrained culture of reporting, backstabbing, and denunciation. Shortly after Mao’s death, I was befriended by the translators Yáng Xiànyì 楊憲益 and Gladys Yang. Although they joked about the charges of spying and corrupting the young that had landed them in jail for years, their lives had been deeply scarred by betrayal. Soon thereafter, I also encountered Sidney Rittenberg, an American journalist turned Maoist zealot. He was one of the people who had denounced the Yangs. They all lived in the “work unit” compound of the Foreign Languages Press, as did dozens of others who had turned on their colleagues in the exuberant early phase of the Cultural Revolution. Veteran editors and translators I now met were forced to share an office, or even a desk, with people who had tormented them, tortured their colleagues, and even murdered their friends. Heartbreak and trauma cast an unavoidable shadow over the post-Mao euphoria of what would become the Reform era. That shadow has stayed with me ever since.

From the early 1980s, the focus of my work was on the cultural figures of the Republican era who had been caught between political extremes. Relegated to the “dustbin of history” after 1949, they were now gradually reevaluated as being crucial to China’s agonized search for modernity. My interests granted me entrée to a revived world of letters and publishing, just as a sensibility formed by the counterculture of the 1960s led to my involvement with the unofficial arts scene. Both aspects of my work skirted around the forbidden zones of Communist Party ideology. As a result, by failing to “stay in my lane” and as an academic who also wrote for the mass media, translated contemporary authors, and frequently broached topics that were permitted one moment and outlawed the next, I frequently found myself at odds with the party-state.

Of the hundreds, possibly thousands of hours devoted to the surveillance of me (and everyone else like me) and the updating of my file, a few moments stand out: During the late 1970s, when the Yangs had introduced me to cultural figures recently returned from internal exile or labor camps, or who were released from prison, the local Party apparat and police were watching; then there was the time in the summer of 1983 when the Central Party Office questioned everyone I knew in Beijing after I visited Mao’s former residence in Zhongnanhai, illegally, as it turned out. Then there were the cautions I was given for writing about the Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign in 1984; the professional anxiety suffered by Linda Jaivin, my partner and the Beijing correspondent for Asiaweek, in 1986 due to the tireless “eyes and ears” as well as the menacing threats made against her friends; the displeasure of the censors that resulted from the monthly Chinese-language column I published in Hong Kong from 1986 to 1991; the intense surveillance I experienced from 1989 to 1992, particularly pronounced whenever I hung out with friends like Liú Xiǎobō 刘晓波 and Dài Qíng 戴晴, both of whom had been jailed for a time after June Fourth.

Then there was the 24/7 intensity of being followed by tag teams of security personnel following the release of our documentary film The Gate of Heavenly Peace in 1995, which the Chinese embassy in Washington decried for having “hurt the feelings of the Chinese people,” and again after Morning Sun, its prequel, screened in 2003. Although overwhelmed by security concerns during the 2008 Olympic year, the “eyes and ears” alerted me to their presence and, when Liu Xiaobo won the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize, security agencies “reached out” to caution me against speaking to the international media while I was still in China. The list goes on… Any misstep could lead to friends and acquaintances being questioned, something that added new notes to their own dossiers and perhaps pages to mine. Despite all of the excitement generated by social and cultural change during the 1980s, and the gradual maturation of China’s academic world, I knew that the organs of the people’s democratic dictatorship — local police, street committees, security agents, spies, party cells — were ever vigilant.

The intensity of surveillance waxed and waned over the years, but it never really let up. Appreciating the inexhaustible mechanisms of the people’s democratic dictatorship and the ideas that underpinned them (an ideology that upheld the unique historical role of the Party, the promise of socialist progress through stages of development, the legacy of colonialism, the threat of neo-imperialism, the ever-present dangers of peaceful evolution, and so on) allowed me to develop a sober, often somber, calculation of what really lay behind the economic statistics and the built wonders of socialist capitalism. It also meant that, from 2008, I was not particularly surprised by the Party’s ever-increasing revanchist mood.

Along the way, I modulated my behavior so that when the scrutiny proved to be too obvious and particularly invasive, I would steer clear of certain friends and warn others. In particular, I tried hard not to lead the security authorities to the homes or back into the lives of anyone who had suffered during the Mao era. Older friends knew when to duck for cover, but it was often necessary to caution younger people about the dangers of a pervasive system that they frequently dismissed as antiquated and irrelevant to their lives.

I also developed the basic social skill of knowing which acquaintances or colleagues I should talk to one-on-one, whom you could meet along with other friends, and which of them it was safe to introduce to others. Academic jealousies and rivalries were insignificant in comparison with the malevolent ley lines that crisscross the landscape of interpersonal relationships. The basic assumption was that someone was always watching and many people were always reporting. So, I was judicious about whom I met, when, and how, and I always made a point of being open about my research and my views. If I was challenged, I was happy to offer a bibliography of my publications — and I did so when I was repeatedly denounced by outspoken and ambitious xenophobes like Hé Xīn 何新, the failed Wáng Hùníng 王沪宁 of the 1980s, and again by the bilious nationalist Wáng Xiǎodōng 王小东.

Resistance and acceptance

As I observed in 2016, experienced China scholars have over long years of engagement worked out how to negotiate their relationships with the Chinese world. In many respects the Olympic year of 2008 presaged Xi Jinping’s China — the anti-foreign protests surrounding reports on the uprising in Tibetan China in the Western press; the stifling Peaceful Beijing Action Plan that reinvigorated the Maple Bridge Experience beloved by Xi Jinping; the hysterical boosterism of the Torch Relay; and the repression of Charter 08 along with the arrest of Liu Xiaobo.

My own sense of what at the time I thought of as “the closing of the Chinese mind” was heightened by contact with security agencies as part of an oral history project on Beijing. Building on insights gained as part of the first survey of the Chinese internet that was commissioned by WIRED in 1997, one that introduced the expression “The Great Firewall of China,” my collaborator and I gleaned some of the future directions of China’s “surveillance state.”

***

It is now over 30 years since Zhōu Lúnyòu 周倫佑, a poet of the “Not-not” (非非 fēi fēi) school in Sichuan, produced his manifesto, “A Stance of Rejection.” Written in response to the cultural capitulation that followed in the wake of the Beijing massacre of June 4, 1989, Zhou’s manifesto called on his fellow writers and artists to resist the blandishments of the state. “In the name of history and reality,” Zhou wrote:

in the name of human decency, in the name of the absolute dignity and conscience of the poet, and in the name of pure art, we declare:

We will not cooperate with a phony value system —

• Reject their magazines and payments.

• Reject their critiques and acceptance.

• Reject their publishers and their censors.

• Reject their lecterns and “academic” meetings.

• Reject their “writers’ associations,” “artists’ associations,” “poets’ associations,” for they are all sham artistic yamen that corrupt art and repress creativity.

Perhaps such hauteur seems too much, even impractical, for the career academic today (it certainly was for Zhou; after all, he went on to enjoy a successful career as a writer and academic). In the era of Xi Jinping, as Official China increasingly limits and polices academic exchange, scholars are confronted with ethical and moral dilemmas.

You are all involved, as I have been, in making a career in and out of China. What does that mean in the present circumstances and, as even many of your fellows would say, “going forward”? In her recent work, the Canadian writer Naomi Klein has focused on the dilemmas of “the doppelgänger world”:

the strangeness so many of us have been trying to name — everything so familiar, and yet more than a little off…That feeling of disorientation — of not understanding whom we can trust and what to believe — that we tell one another about? Of friends and loved ones seeming like strangers? It’s because our world has changed, but, as if we’re having a collective case of jet lag, most of us are still attuned to the rhythms and habits of the place and selves we left behind.

The momentum of Xi Jinping’s rule appears to be inexorable and as Official China increasingly limits and modulates academic exchange, many scholars long involved with the People’s Republic are coming to grips with their own kind of “jet lag.” Some reject China entirely, others hold true to the value of meaningful exchanges, while there are also those straining to salvage something from decades of mutually beneficial engagement. All are confronted with ethical and moral dilemmas. What position will you take?

Of course, one is mindful of the blandishments of academic status, research money and superannuated salaries, position, academic authority, and a stance in regard to the ongoing Sino-international chilly war 凉战 liáng zhàn. In this new age of Silent China (无声的中国 wúshēngde zhōngguó), of a stifling Iron Room (铁屋 tiě wū) in which everyone is awake to one extent or another, when and how do you speak out? Or do you prefer to come to an accommodation with the architects of The China Story and Xi Jinping’s Chinese Dream of the Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation?

I would suggest that a strategic stance of principled resistance is more necessary now than ever: resistance in regard not only to the enticements of a comfortable engagement with China’s party-state, but a canny resistance, too, in response to the hyperbolic language of Cold War, the verbiage of untruth, and the strategies of careerism.

In my own case, after three-and-a-half decades of living with China, I chose an expression I had learned from reading classical history to encapsulate the kind of deal I was prepared to cut both with China and with the academic world that I inhabited in Australia. I would be a zhèngyǒu 诤友 — that is, a person who, despite their friendly disposition, always strives to place principle ahead of accommodation — when relating to China, officially or through my work, and as an academic in my own surroundings.

The idea is simple: to reject the black-and-white dichotomy demanded of China’s (and for that matter the “West’s”) Cold War approach. In my case, the stance of the zhengyou is grounded in liberal humanist values that defend independent thought, speech, association, and scholarship, while meaningfully and respectfully engaging with the Chinese world, which exists on a spectrum.

At one end, Chinese friends and colleagues offer an enthusiastic embrace, while at the infrared end of the spectrum, you are met with suspicion and self-regarding aloofness. From 2008, I argued that principled difference and reasoned contrariness were also the basis for the kind of independent scholarship that I personally pursue. The concept of zhengyou also underpinned the research center that I created in 2010 with the support of Kevin Rudd, then the prime minister of Australia, and its dealings with China, be it the People’s Republic, Taiwan, Hong Kong, or the broader Chinese world. In China’s Unfinished Twentieth Century, the editorial I wrote for the final issue of China Heritage Quarterly, the precursor to China Heritage, I surmised the underpinnings of my stance in a quotation about the novelist Shirley Hazzard:

…liberal humanism does not have a geographic home; it is not fixed in space, does not emerge from a single source. Rather its fragile decencies are founded on connections between disparate individuals, creative artists and people-smugglers of the intellect who carry other people’s words around inside their heads.

On balance, it is more likely than not that many readers of this essay will outlive Xi Jinping’s reign (having survived one bout of cancer, but living with its “long tail,” I do not expect the same for myself). You are engaged with a Chinese world that, despite the best efforts of the Communist Party, its obsession with security and spies, its crippled academic world, the propaganda organs and twisted party-state education and indoctrination, thrives in a myriad of ways. Xi’s China may appear to be “stagnant,” but despite the superficially placid appearances, there are countless roiling internal waves and currents. Contact with a vital, complex, contradictory China is both possible and still exciting, and you can find ways to join in fellowship with friends, colleagues, and mentors in the Chinese world, or what I think of as The Other China.

Ten watchwords for working with Xi Jinping’s China

For watchful individuals, the political biorhythms of post-Mao China were easy enough to detect. Each contraction — in 1979, 1981, 1983, 1987, 1989, 1999, 2003, 2008, 2011, and then suffocatingly steadily from late 2012 — has demanded a strategic response, even as each relaxation gave the impression of a progressive opening up. Over the decades, canny Chinese colleagues have readily exploited every opportunity that presented itself to write, publish, and convene before encountering the next treacherous zigzag on the political road.

Below, I offer 10 watchwords or cautions for those who wrestle with the conundrum of how to deal with contemporary China. These are primarily reminders to younger scholars or those who are relatively new to Chinese studies. Established academics will have long ago developed their own professional demeanor and personal strategies of coping with Xi Jinping’s China.

1. Surveillance

Remember that, even before the era of mass data collection, there would have been one or more dossiers or personnel files devoted to you that were lodged with one or more of the organizations that oversee your life in China (or, for that matter, in your country of origin). These would be frequently updated on the basis of your activities as well as with information provided directly or indirectly by colleagues and friends, some of whom are required to inform on you, while others do it voluntarily.

For an insight into the analogue age of surveillance under late-state socialism, I would recommend The File: A Personal History by Timothy Garton Ash. Today, there are more “eyes and ears” working on both sides of the divide, both in as well as outside of China. In April 2023, Beijing’s expanded anti-espionage legislation added a repellent new dimension to the insecurity of visitors and residents alike. One should, therefore, remember that in dealing with suspicious individuals, your mantra should always be “I don’t know anything” (一问三不知 yī wèn sān bù zhī).

2. Collaborations

These can be exciting, productive, and crucial to expanding one’s understanding and appreciation of — not to mention empathy with — colleagues in China. They can, however, also come at a cost to all of those involved.

In formal terms, academic collaborations are overseen by Party committees and their agents at all levels. As a result, academics are constantly negotiating relationships. For the most part, you should be mindful of the fact that Xi-era academics are fundamentally members of the Skin-and-Hair Intelligentsia (皮毛知识分子 pímáo zhīshì fènzǐ), that is, the echelon of educated people created by Mao in the 1950s, and groomed under Xi Jinping: They are reliant on Party largesse and most (although by no means all) are incapable of substantially independent and effective intellectual and critical engagement with the nation’s political life.

Some scholars claim that China’s “intellectual ecology” is in certain regards pluralistic, but this is a smug fiction. It is an ecology shaped by the devastating Agent Orange of censorship and kept weed free by coercion, self-censorship, complicity, and fear. Certain measures of latitude exist by necessity, but these can be stifled at a moment’s notice. Your understanding of the give-and-take required in dealing with scholars and others in an ever-increasingly complex political landscape will develop over time. Therefore, it is necessary to be aware of the ethical dimension of your activities, not merely as determined by your home university via pro forma “ethics clearances” overseen by academic invigilators, but also as an engaged and thoughtful individual.

China constantly confronts you with situations that challenge your basic values and judgements. You need to work out how to unravel knotty problems not only for your own sake, but also for the sake and safety of others. Official collaborations will offer some scope for serious academic work, but you should also be mindful that since China’s academic system is unabashed about its politicized and repressive norms, it remains eager to advertise international partnerships, both as a measure of self-validation and for the sake of currying favor with the Party.

Of course, the term “collaboration” also has a more sinister meaning. I would ask you to remember that whenever you enjoy an official banquet, or join in one of those mandatory group photo ops with smiling academic bureaucrats, you are signaling to those absent colleagues — people who you are forbidden from or now reluctant to work with due to the changed political climate, as well as those who have been relegated to the ranks of Former People — that you are quietly, if inadvertently, adding your weight to their benighted state. Furthermore, you might be allowed privileged access to certain controversial people or forbidden topics, but this is done on the understanding that you do not publicize the fact. Such “insider access” can come at a cost to your own integrity. You might excuse your ongoing collaboration with an official academic culture suffused with lies, distortions, and silence because, after all, individual access can also contribute to the greater good — you are helping to keep channels of communication open and you’re playing a useful intermediary role (not to mention the fact that you also happen to be benefiting your own career and enhancing your sense of self-importance along the way).

3. Conflict

One way or another, you are involved in a multifaceted historical and ideological contestation that has been unfolding since 1917. It is incumbent upon you to study the Chinese context of this conflict, and how your own position and the historical environment in which you live and work relate to it. In particular, you should familiarize yourself with Mao Zedong’s response to the 1949 U.S. White Paper on relations with China and the theory and practice of the policy of “peaceful evolution” from 1959.

You should be aware that China’s own entrenched “Cold War thinking” underpinned the Anti-Bourgeois Liberalization Campaigns of 1983 and 1987, just as it did again in 1989. The powerful nexus of ideas and policies resulting from that era — yes, the Deng era! — forms the bedrock of Xi Jinping’s view of the party-state. To appreciate the clash of ideologies, and empires masquerading as civilizations, requires more than a fitful reading of mass media Party propaganda.

4. Self-censorship

I recommend the insightful account of China’s culture between the lines by Xǔ Zhīyuǎn 许知远, a cultural entrepreneur who has continued to flourish under the present draconian regime. Scholars shape their research agendas for legitimate intellectual reasons, but a cynical research life reflects as much on your scholarship as it does on yourself.

As Simon Leys noted long ago:

In the foreword to the 1977 edition of his classic essay on Stalin, originally published in 1935, [Boris] Souvarine recalls the incredible difficulties he had in finding a publisher for it in the West. Everywhere the intellectual elite endeavored to suppress the book: “It is going to needlessly harm our relations with Moscow.” Only Malraux, adventurer and phony hero of the leftist intelligentsia, had the guts and cynicism to state his position clearly in a private conversation: “Souvarine, I believe that you and your friends are right. However, at this stage, do not count on me to support you. I shall be on your side only when you will be on top (Je serai avec vous quand vous serez les plus forts)!” How many times have we heard variants of that same phrase! On the subject of China, how many colleagues came to express private support and sympathy (these were still the bravest!), apologizing profusely for not being able to say the same things in public: “You must understand my position…my professional commitments…I must keep my channels of communication open with the Chinese Embassy. I am due to go on a mission to Peking…”

In this context, I would also recommend J.M. Coetzee’s Giving Offense: Essays on Censorship and An Educated Man Is Not a Pot, published online by China Heritage.

5. Zhèngyǒu 诤友

See the above. In 2018, 10 years after having first suggested that the concept of the zhengyou might be useful in Sino-Other relations, I observed that:

As the People’s Republic of China, a country that is tirelessly alert to perceived slights, plots, and hints of containment, continues to warn darkly of the threat of a new Cold War — and as it responds to the fears in the Antipodes, Europe and North America that its “united front” work among patriotic Chinese is also a front for a political and economic fifth column — the pursuit of principled yet amicable disagreement appears even more distant than when Kevin Rudd addressed that audience at Peking University [in April 2008]. In an international environment in which borders, walls and paranoia inform public opinion as well as political action, principled friendship may be nothing more than the nostalgic luxury for an imagined past. … Now, as was the case 10 years ago, to be a principled friend who dares to disagree, one first and foremost needs principles, and not merely transactional tactics.

6. Reading

Apart from the works related to the century-long conflict mentioned above, I would also recommend the series Homo Xinensis, which traces ideas related to China’s “party empire,” the ongoing attempt by the power holders to remake the “Chinese national character,” and student militance from the late 19th century.

In regard to Chinese/China studies, scholars should also familiarize themself with the discussion about disciplines and Sinology in 1964, as well as such works as How to Resist China’s Influence by scholars at the think tank MERICS, and the efforts of groups such as Critical China Scholars and the Chinese Students and Activists (CSA) Network, both of which offer important perspectives on the issues at stake in working with and about China.

New Bloom magazine produced by Brian Hioe is a useful alternative to mainstream opinion on Taiwan, while the scholarship of Anne-Marie Brady on propaganda and foreign influence remains as relevant as ever.

You should also be familiar with the white papers on various current issues produced by the Chinese government. Study also the underpinnings of Xi Jinping Thought and read what he and official commentators say, not just about your own area of interest, but in relation to the broad context of party-state ideology and policy. Only when you know the contours of the official “line” will you readily be able to recognize the variations of it when they are fed to you by your interlocutors. Today, there are many independent websites, substack analysts, YouTube channels, podcasts, and newsletters that can help you understand Official China. Similarly, familiarize yourself with the history, artifice, and fallacies of false analogies and “whataboutism.”

7. Listen

There are rich resources for appreciating both Official and Other Chinas. For all of the limitations of the Xi Jinping era, and the closing down of access to academic resources, scholars of China can still access a wealth of non-academic literary, audiovisual, and cultural material. See, for example, Voices from The Other China — Ten Podcasts & Twenty YouTube Channels and the material in The Other China.

8. Survivors

You may well be familiar with human rights issues and injustices in your home country, as well as the controversies regarding human rights in mainland China and Hong Kong. But in dealing with the P.R.C., it is now also important for scholars to acquire some visceral appreciation of the breadth and depth of the issues. I therefore suggest that you try to meet and get to know some people who have direct experience of the repressive mechanisms of the Chinese state.

It is increasingly possible for you to interact with people who have been jailed, spent time in reeducation camps, or undergone thought reform in China. Look them in the eye, listen to their stories; familiarize yourself with everyday forms of control. Some of the observations that Simon Leys made about human rights in China decades ago are still relevant today: “If Soviet dissidents have, on the whole, received far more sympathy in the West,” Leys observed, “is it because they are Caucasians — while the Chinese are ‘different’?”

Leys elaborated:

When Maoist sympathizers use such arguments, they actually echo diehard racists of the colonial-imperialist era. At that time the “Chinese difference” was a leitmotiv among Western entrepreneurs, to justify their exploitation of the “natives”: Chinese were different, even physiologically; they did not feel hunger, cold and pain as Westerners would; you could kick them, starve them, it did not matter much; only ignorant sentimentalists and innocent bleeding-hearts would worry on behalf of these swarming crowds of yellow coolies. Most of the rationalizations that are now being proposed for ignoring the human-rights issue in China are rooted in the same mentality.

Here I would note that according to Freedom House, there have been more than 2,800 “dissent events” in China since June 2022, including “70 cases of dissent by Tibetans and Mongolians.” Similarly, labor protests are on the rise, reflecting the poor state of the economy.

9. What’s possible?

As I observed in the introduction to the series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium:

For those who live in a global Chinese world long nurtured by the riches of Taiwan and Hong Kong, as well as by a Mainland revived during the decades of economic reform and the creativity of communities in the Chinese diaspora, it is a tragedy of immense proportions that a clutch of rigid, nay-saying bureaucrats thus holds sway, that it arrogates to itself the power to legislate and police the borders of what by all rights should be a cacophonous multiverse of Chinese possibility.

By imposing an educational regime that, to quote Xi Jinping, “grabs them in the cradle,” by creating a censorious media monolith that spews forth a carefully curated “China Story” and by pursuing a “chilly war” internationally with the encouragement of battalions of online vigilantes, the Party continues to terraform China and create a monotone landscape. All of this is aided and abetted by a sharp-edged new phase in a century-long contestation with the United States and the Western world. Although Xi Jinping’s enterprise builds on the twisted legacy of the Mao era and the darkest aspirations of the Deng-Jiang-Hu reform decades, it is obvious that his Empire of Tedium is also the handiwork of willing multitudes who travail at the behest of one man and the party-state army that he dominates.

Regardless of this glum assessment, there is ample evidence that a parallel academic world exists in China today. Both collective and individual research projects are still being pursued on the down-low. At some point in the future, “writing done for the drawer” (抽屉文学 chōutì wénxué), as it is called, even in the digital age, will see the light of day.

Meanwhile, some younger scholars of China, and numerous individuals whose lives are enmeshed with China around the world are finding ways to collaborate and create in their own communities and across borders. These vistas are still relatively open and potentially limitless. In the meantime, there are scholars and students in China itself who, despite all obstacles, continue to pursue the ideal of having an “independent spirit and an unfettered mind” (獨立之精神,自由之思想 dúlì zhī jīngshén, zìyóu zhī sīxiǎng) advocated by the celebrated historian Chén Yínkè 陈寅恪 nearly a century ago.

10. Whores and monuments

Be mindful of the lure of self-justification. A popular Chinese saying puts it like this: “While you behave like a whore, you actually think that you deserve to have a commemorative arch set up in praise of your virginity” (既要做婊子, 又要立牌坊 yòu xiǎng dāng biǎozi, yòu xiǎng lì páifāng).

Don’t fool yourself into believing that you can cut a deal with Official China and escape the scrutiny of Unofficial China. Agents of the party-state are not the only ones who are watching what you do and keeping a record.

If this all sounds too harsh, then I’m sorry to “yuck your yum.” This is the environment in which you are working and the price of admission doesn’t come cheap.

***

The banquet of China

An equitable and open intellectual relationship with China is simply not possible under Xi Jinping’s pusillanimous rule. The Chairman of Everything may well lay claim to what I think of as terminal tenure, but he is no Mao Zedong and China is not simply in the throes of Cultural Revolution 2.0.

By the same token, the kumbaya China that some foreigners imagined was possible in the past is a mirage.

Since addressing the Shanghai International Literary Festival in 2017, I have been focussed on China Heritage. Among other things, I have created an archive related to Xǔ Zhāngrùn 许章润, formerly a professor of jurisprudence at Tsinghua University and Xi Jinping’s most implacable critic. Hong Kong Apostasy follows the death throes of that unique social and cultural entrepôt and Viral Alarm provided a record of the COVID years. Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium is an ongoing chronicle of the present while in The Other China I share insights into the thriving multiverse that exists both in tandem with as well as opposition to the overculture of the party-state. In 2024, I plan to launch “The Tower of Reading” (唸楼 niàn lóu), an addition to my work on New Sinology. I’ve yet to have an opportunity to return to the People’s Republic, although, conditions permitting, I certainly plan to do so.

Each of us must decide what we are willing to do to accommodate Xi Jinping’s “Iron House,” just as we must decide whether we will partake of what, in 1925, Lu Xun called the “banquet of China”:

Feasts of human flesh are still being spread, even now, and many people want them to continue. To sweep away these man-eaters, overturn these feasts and destroy this kitchen is the task of the young folk today!

这人肉的筵宴现在还排着,有许多人还想一直排下去。扫荡这些食人者,掀掉这筵席,毁坏这厨房,则是现在的青年的使命!