‘Pocket crime’ — Phrase of the Week

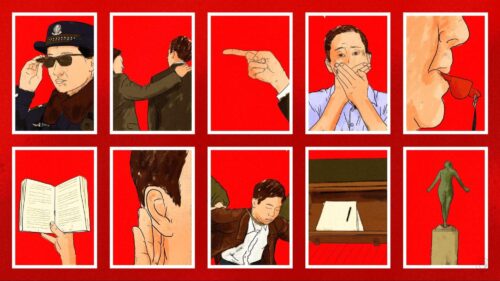

A new draft law in China may dole out punishments for “harming the feelings of the Chinese people.” It has sparked criticism in China.

Our Phrase of the Week is: Pocket crime (口袋罪 kǒudài zuì).

The context

A draft amendment to China’s Public Security Administration Punishments Law (治安管理处罚法 zhì’ān guǎnlǐ chǔfá fǎ) was published on the Chinese People’s Congress website on September 5. It is open for public consultation before China’s lawmakers finalize changes to the law.

One proposal in the draft has sparked debate in China:

In this revision, the second and third paragraphs of Article 34 indicate newly added behaviors that should be punished, including “wearing clothes and accessories in public places that are detrimental to the spirit of the Chinese nation and hurt the feelings of the Chinese nation”; and “producing, disseminating, and publicizing things or remarks that are harmful to the feelings of the Chinese people.”

在该修订中,第三十四条的第二款和第三款意见显示了新增应处罚的事项,包括“在公共场所穿着、佩戴有损中华民族精神、伤害中华民族感情的服饰、标志的;制作、传播、宣扬、散布有损中华民族感情、伤害中华民族感情的物品或者言论的。

Zài gāi xiūdìng zhōng, dì sānshísì tiáo de dì èr kuǎn hé dì sān kuǎn yìjiàn xiǎnshìle xīnzēng yīng chǔfá de shìxiàng, bāokuò “zài gōnggòng chǎngsuǒ chuānzhuó, pèidài yǒusǔn zhōnghuá mínzú jīngshén, shānghài zhōnghuá mínzú gǎnqíng de fúshì, biāozhì de; zhìzuò, chuánbò, xuānyáng, sànbù yǒusǔn zhōnghuá mínzú gǎnqíng, shānghài zhōnghuá mínzú gǎnqíng de wùpǐn huòzhě yánlùn de.”

Recommended punishments under the proposal include detention of up to 15 days and fines up to 5,000 yuan ($688).

But “harming the feelings of the Chinese people” is vague and subjective, as one commentator notes:

The meanings of “harming the spirit of the Chinese nation” and “hurting the feelings of the Chinese people” are ambiguous. If implemented, it may be a typical “pocket crime,” which is likely to be abused.

“有损中华民族精神”、“伤害中华民族感情”含义模棱两可。如果实行的话,则可能是典型的“口袋罪”。有可能同饱受争议的寻衅滋事罪和曾经的流氓罪一样,极大可能被滥用。

“Yǒusǔn zhōnghuá mínzú jīngshén,” “shānghài zhōnghuá mínzú gǎnqíng” hányì móléng liǎngkě. Rúguǒ shíxíng de huà, zé kěnéng shì diǎnxíng de “kǒudài zuì.” Yǒu kěnéng tóng bǎoshòu zhēngyì de xúnxìn zīshì zuì hé céngjīng de liúmáng zuì yíyàng, jí dà kěnéng bèi lànyòng.

And with that, we have our Phrase of the Week.

What it means

Pocket crime is a Chinese legal term first coined in 1979. It describes a crime category that is vague, broad, and can be open to interpretation and abuse by law enforcement authorities.

Three types of crime were identified as pocket crimes in 1979:

The crime of capitalist speculation, the crime of hooliganism, and the crime of dereliction of duty.

投机倒把罪、流氓罪和玩忽职守罪。

Tóujīdǎobǎ zuì, liúmáng zuì hé wànhū zhíshǒu zuì.

These crimes were further defined in an attempt to bring more clarity and less ambiguity to the law: For example, hooliganism (流氓罪 liúmáng zuì) was divided into a number of crimes that were supposed to be more specific. One of those was picking quarrels and provoking trouble (寻衅滋事 xúnxìn zīshì).

Picking quarrels and provoking trouble has also become controversial in recent years for the same reasons, and has been described as a “pocket crime.” The scope of its definition was broadened in 1997, and then again in 2013.

These changes have been criticized as part of the increasing suppression of civil society in China.

In August this year, an investigation by China’s High Court found that picking quarrels and provoking trouble was also being used widely and abused by law enforcement officials. And this week, it was reported that an American citizen had been detained in China under the crime in 2020, and has recently been released.

The latest draft amendment to China’s Public Security Administration Punishments Law is potentially another capacious grab-all category of criminality akin to picking quarrels and provoking trouble, notes Geremie R. Barmé, the editor of China Heritage.

So our translation of this week’s phrase is: “A nebulous catchall legal instrument open to interpretation and abuse.”

With thanks to Geremie R. Barmé, editor of China Heritage, for contributing to this week’s Phrase of the Week.