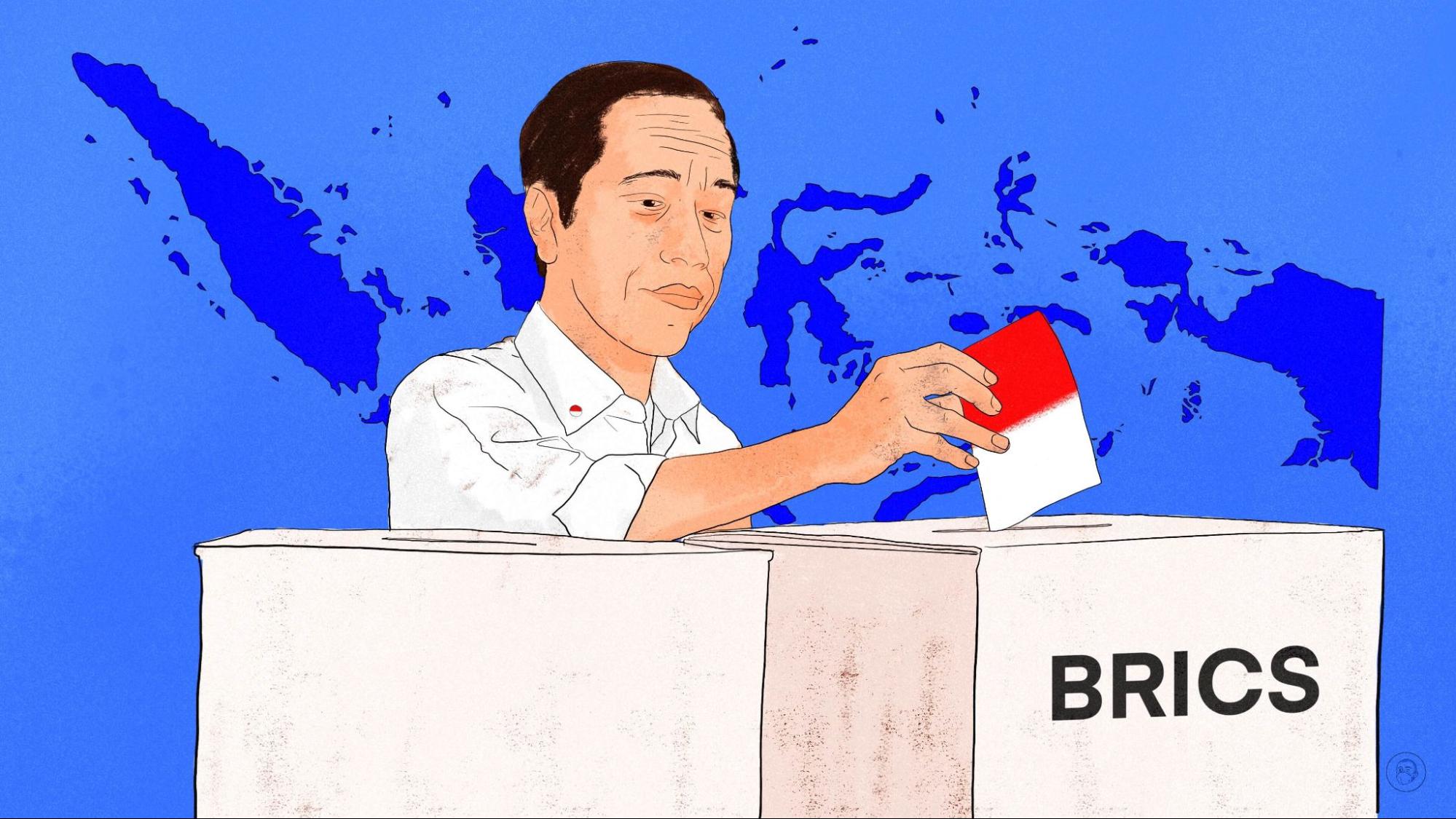

Why Indonesia did not join BRICS

Indonesia has a tricky balancing act to pull off right now. Like many countries, it’s stuck between a Chinese rock and an American hard place. This is what’s at stake.

Last month’s BRICS summit in South Africa ended with Indonesia not joining the group. Some wondered why the country did not become a new member. After all, Indonesia is a Global South nation with one of the world’s largest populations and economies, and a history of developing country leadership: The first large-scale Asian-African get-together, the Bandung Conference, took place in 1955 in Bandung, Indonesia.

After participating in the summit, Indonesian President Joko Widodo made it clear that his administration was “reviewing and considering the country’s possibility of joining” the group, according to a government statement.

“We intend to conduct a thorough study and calculation. We do not want to make any hasty decision,” said the president — popularly known as Jokowi — on August 24.

“To become a new member of the BRICS group, a country must submit a letter of expression. Until now, we have not submitted that.”

Tri Tharyat — the Indonesian foreign ministry’s director general for multilateral cooperation — told The China Project on August 29 that he had no further comment on BRICS because “the president had made an official statement.” He did not respond when asked when the government would submit the letter.

“Incredible” ties

Jokowi said, “Our relations with the five BRICS member countries are also incredible, especially on economic cooperation,” referring to Indonesia’s strong relations with the group’s founders — Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.

The president also said on August 24: “We must reject trade discrimination. Industrial downstreaming should not be obstructed. We all must keep fighting for equal and inclusive cooperation.”

“BRICS can serve as ‘the forefront’ to fight for development justice and fairer world governance reformation.”

As the world’s fourth-most-populous state, Indonesia has a rising economic and diplomatic influence. The country is a G20 member and hosted last year’s summit during its presidency — attended by China’s leader, Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 — in Bali in November.

Earlier this month, Southeast Asia’s largest economy welcomed the leaders of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and other countries — including Chinese Premier Lǐ Qiáng 李强 — at a Jakarta summit under the republic’s chairmanship.

Yet Indonesia has substantial trade relations with individual BRICS founding countries.

According to Statistics Indonesia (BPS) government agency, the country of over 275 million people exported goods worth a FOB value of over $65.8 billion to China in 2022 — the largest of all countries listed. It had an export value of above $23.3 billion to India, over $1.3 billion to Russia, more than $1 billion to South Africa, and over $1.4 billion to Brazil.

Indonesia’s Vice Trade Minister Jerry Sambuaga said in mid-August that the country would be able to explore “nontraditional” markets in Africa and Latin America by making South Africa and Brazil entry points to those regions, respectively, if it were part of the BRICS.

Out of all BRICS founding members, Indonesia also has more extensive investment ties with the People’s Republic. According to the country’s Investment Ministry, mainland China was the second-largest investor throughout 2022, with $8.2 billion, and Hong Kong was third at $5.5 billion. The other original BRICS members did not make the top 20 list that year.

Nur Rachmat Yuliantoro, the head of the Department of International Relations at Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM) in the Indonesian city of Yogyakarta, said Indonesia needed to consider “good relations with these four countries” besides China, although “it cannot be denied that China is one of the central powers, if not the most important, of BRICS.”

“Indonesia must not depend only on its good relations with China, but it must also pay attention to the interests of other countries so that their representation in BRICS is respected,” he said.

Siding with any party?

Johanes Herlijanto, the co-founder and chairman of the Indonesian Sinology Forum (FSI) — an NGO that researches Indonesia-China ties — in the Indonesian capital, Jakarta, said, “China’s dominance in BRICS, as well as Russia’s support, will put Indonesia in a difficult situation if we join without doing calculations.”

“If BRICS’ main power China pulls Indonesia to show its side, this is certainly not advantageous for Indonesia. That is why Indonesia’s statement that we are still considering is the right statement,” he told The China Project.

“The problem is that BRICS in recent years has behaved like a bloc, which is certainly not in line with Indonesia’s principle of maintaining a neutral position.”

Rachmat of the UGM said the United States and its allies could see Indonesia “in a disadvantageous context” if the latter joined the BRICS.

“Therefore, what is best for Indonesia at the moment is to wait and see first, not to rush into joining the BRICS, while trying to maintain broad support for its foreign policy,” he said.

Indonesia has implemented a “free and active” foreign policy; the principle drives it not to side with any major global power. By extension, Rachmat said the country’s main challenge in becoming a BRICS member would be to “convince the international community, especially the United States and its allies, that this participation does not violate non-aligned principles and is aimed solely at Indonesia’s national interests.”

FSI’s Johanes said, “If Indonesia becomes part of the BRICS, it will add to the strength of this group, and of course, has the potential to change the geopolitical balance, although it all depends on Indonesia’s own attitude.”

“Can Indonesia, if it joins [the BRICS], only focus on taking benefits for Indonesia, without participating in issues that can potentially escalate tensions?” he said.

Yet Rachmat said the impression — if Indonesia joined the BRICS — that the country “sided with China” and became “anti-West” would be misleading.

“Indonesia does not need to be afraid of being labeled as an anti-Western country, considering that Indonesia’s geopolitical and geoeconomic potentials cannot be dismissed,” he told The China Project.

“The United States and its allies, as well as China and other BRICS countries, have and will continue to view Indonesia as a country with great regional influence.”