BRI at 10: China’s Maritime Silk Road

Beijing aspires to a leading position on the high seas. This has made multiple countries uncomfortable, for different reasons.

Foreign leaders are converging in Beijing tomorrow for the third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, demonstrating that the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) continues to hold currency, globally and within Chinese foreign policy.

However, the BRI of 2023 is not the BRI of 2013. The initiative has faced some adjustment at the policy level, but the BRI has also shifted simply because China’s global footprint is constantly evolving. The focus on renewables, for example, is not led purely by ministerial guidelines, but by host country demand.

In 2019, I spent a year traveling overland from the U.K. to Vietnam, visiting Belt and Road projects and talking to people about the impact of China’s ambitions. This year, I marked the BRI’s anniversary by heading back out on the road to see what has changed, and have produced this four-part series called the Belt and Road Dispatch. The other pieces in this series looks at:

The physical reality of the BRI — consisting of the projects that identify with the initiative — remains an eclectic, ad-hoc collection of investments, deals, and initiatives. It will remain ever necessary to scrutinize how they play out on the ground.

I pull up outside the China-UAE Industrial Capacity Cooperation Demonstration Zone intending to take some photos of the site. The China-UAE project is in the Khalifa Industrial Zone, a desert logistics hub that Abu Dhabi Ports has set up right next to its flagship Khalifa Port in Abu Dhabi. The highway is empty and there are no guards, but the structures around the road are bristling with surveillance cameras.

When I’m refused an official site visit, I usually turn up under my own steam and take photos, but this feels riskier than usual. Governments are sensitive about port infrastructure at the best of times, but this is especially true when you’re suspected of hosting a secret Chinese military facility.

The reports, based on U.S. intelligence leaks, don’t indicate the exact location of the alleged facility, but Chinese shipping giant COSCO Shipping does own the CSP Abu Dhabi Terminal at Khalifa Port. It won the 35-year concession to develop the new terminal back in 2016, not long after Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 signed an agreement for the China-UAE Industrial Capacity Cooperation Demonstration Zone.

Both the port terminal and demonstration zone are of course proudly part of the Belt and Road Initiative — more specifically, the maritime road component of the BRI. At the inauguration ceremony for the new CSP Abu Dhabi Terminal in 2018, China’s deputy minister for transport called the terminal a “major achievement from China and [the] UAE’s joint efforts to implement the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road.”

The perimeter of the Demonstration Zone is also lined by slogans such as “walk the road of peace and win-win, inherit the Silk Road spirit.” The project is led by the Jiangsu Overseas Cooperation and Investment Company (JOCIC), a consortium of companies from the Chinese province of Jiangsu. Due to successful lobbying efforts by the local government, Fujian is the province most associated with the 21st Maritime Silk Road (MSR), but Jiangsu also made a successful campaign of marketing itself as being on the crossroads between the West-facing Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) and the East-facing 21st Maritime Silk Road.

In the tradition of province-state pairings, Jiangsu is also the Chinese province with deepest ties to the UAE, and it was appointed in 2016 to lead the Development Zone project. Two years later, ground was broken on a 2.2-square-kilometer patch of land dedicated to high-end manufacturing, and this year infrastructure was completed.

Unlike many BRI projects, which are simply branded BRI retrospectively for the sake of political convenience, Khalifa Port and the Development Zone can make a robust claim to be in line with Beijing’s strategic vision. Khalifa is typical of Beijing’s “industrial park-port interconnection, two-wheel and two-wing approach” to BRI development in the Middle East, and is one of four such park-port complexes arranged in a horseshoe from the Gulf up to the Mediterranean.

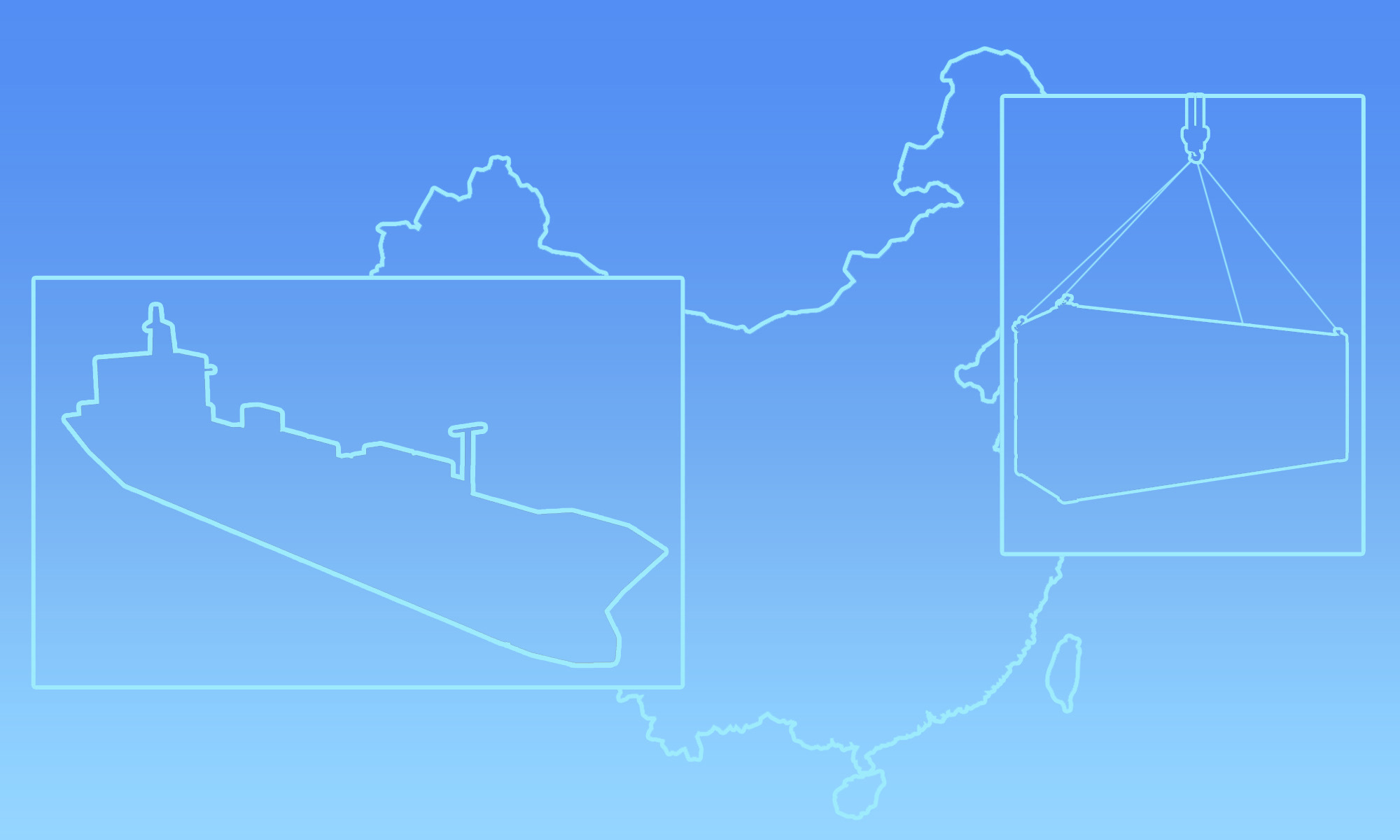

Maritime Silk Road

Confusingly, it’s the “belt” — the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) — that goes overland, and the “road” — 21st Maritime Silk Road (MSR) — that goes by sea. The SREB was announced by Xi Jinping in the capital of Kazakhstan on September 7, 2013, and the MSR came less than a month later, announced by Xi at the Indonesian parliament. As with the SREB, rhetoric around the MSR is steeped in “Silk Road Spirit,” mostly through allusions to the legendary Ming dynasty admiral Zhèng Hé 郑和.

According to the “Vision for Maritime Cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative,” issued in June 2017 by the powerful National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the State Oceanic Administration, the MSR consists of three “blue passages:” 1) China through the Indian Ocean, to Africa, and the Mediterranean; 2) China to the South Pacific; and 3) China-Europe via the Arctic.

As with corridors under the SREB, these “blue passages” are clearly very broad and offer more of a loose, conceptual framework than a concrete blueprint. However, as the concrete reality of Beijing’s “industrial park-port interconnection, two-wheel and two-wing approach” demonstrates, these strategic visions are perhaps taken a little more seriously along the MSR.

China’s expanding “port-folio”

The cross-continental “New Silk Road” element of the BRI has captured the public imagination, but continental traffic is miniscule compared to maritime trade, with a full 95% of China’s foreign trade going by sea.

Given this reality, as well as the fact that China is the world’s largest trading nation, it is unsurprising that Beijing aspires to a leading position on the high seas. Even before the BRI, Hú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛 was calling for China to become a “strong maritime power,” and when Xi assumed the presidency in 2013, he incorporated this ambition into his “China dream” and the BRI.

The modernization of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy is an obvious component of this strategic goal, but the expansion of China’s merchant navy is just as vital to the achievement of maritime power. Today, China is already a dominant force in maritime trade: it is the world’s largest shipbuilding nation, has the world’s largest merchant fleet, and owns or operates 96 terminal assets in ports worldwide.

The second and fourth largest port operators in the world are Chinese state-owned enterprises: COSCO Shipping and China Merchants Group. Both have been aggressively expanding their portfolio of overseas terminals under the banner of the Maritime Silk Road. Of these two companies, COSCO is particularly formidable — not only is it the world’s second largest terminal operator, it is also one of the world’s largest container shipping companies.

Overseas terminal acquisitions are vital to China’s control of the seas, allowing greater market access, efficiency gains, and reduced shipping costs for Chinese companies. The new terminal built with Abu Dhabi Ports at Khalifa was the first overseas terminal that COSCO built from scratch. When it was inaugurated, it more than doubled Khalifa Port’s capacity and gave COSCO a foothold in the Gulf of Arabia, a vital gateway to the Middle East North Africa region, and greater control over shipping routes to countries in the west.

U.S. suspicion of military facilities

The U.S. government is particularly concerned about China’s burgeoning “port-folio,” focusing on security concerns that these ports might be part of Beijing’s efforts to extend its military capabilities. China’s overseas port facilities are for commercial use, but the fear is that they might easily be upgraded to carry out military missions.

Besides this inherent dual-use potential, the United States is also concerned that Beijing is actively establishing military bases at some of these maritime footholds. The U.S. has military installations in dozens of countries worldwide, but to date, China has only one confirmed overseas military base, in Djibouti. However, there have also been credible reports that China is building a naval facility in Cambodia, on the Gulf of Thailand.

The alleged Chinese military installation at Khalifa was first reported in November 2021. According to the reports, construction ceased after complaints to UAE authorities, but in April this year classified documents leaked to the messaging platform Discord revealed that the U.S. intelligence community suspected the military buildup at Khalifa to have resumed.

According to the leaked materials, the Khalifa site is part of what Chinese officials call “project 141” — a PLA initiative to build five overseas bases and 10 logistical support sites by 2030.

COSCO’s port expansion in Europe

Fears in Europe about China’s port expansion have been focused closer to home. The nearest China comes to control of any U.S. ports is through China Merchant Ports’s 49% stake in majority French-owned company Terminal Link, which owns two container terminals at the Port of Miami and the Port of Houston.

That is not the case in the European Union, where COSCO Shipping and China Merchants Group own stakes in over a dozen container terminals. COSCO owns controlling stakes at two European ports: CSP Zeebrugge Terminal in the Netherlands and Piraeus in Greece. The presence in Piraeus is very significant — COSCO owns 100% of Piraeus Terminals 1 and 2, plus 67% of the Piraeus Port Authority, and under COSCO’s active leadership, Piraeus has become the fifth busiest port in the EU, up from 17th place in 2007.

Scrutiny of China’s port acquisitions in Europe peaked after it was announced last year that COSCO would take a 35% stake in Container Terminal Tollerort GmbH (CTT) at the Port of Hamburg, which advertises itself as a “Gateway to the New Silk Road.” The deal was a focal point of fighting within the German coalition government about the direction of Germany’s China policy, with Chancellor Olaf Scholz urging the deal forward and several important ministries resisting on national security grounds. In the end, the chancellor pushed through a compromise, capping COSCO’s stake at 24.99% and limiting its strategic control.

The concern around Hamburg is not so much over the dual-use nature of facilities, since European governments are unlikely to ever host Chinese military installations and Chinese concessions would be irrelevant in a wartime scenario. The main fear is regarding the influence Beijing could leverage through its control of critical infrastructure.

But influence is notoriously difficult to measure. COSCO’s central role in the Greek economy probably will make Greek elites more wary of angering China, but COSCO also has genuine commercial interests in Piraeus, and is unlikely to use its position coercively.

The biggest threat from COSCO’s acquisition spree is probably a commercial one. Europe currently boasts four of the five largest shipping companies in the world. The only other company in the top five, at position number four, is COSCO. But with a protected domestic market, a cost-cutting supply chain of state-owned enterprises, and access to cheap capital, COSCO threatens Europe’s commanding position.

The industry-wide trend in shipping is toward greater vertical integration and consolidation. This consolidation has created what is essentially an oligopoly of three shipping alliances, and COSCO is a dominant member of the OCEAN alliance, the largest of these three groups. For ports like Hamburg, the choice is between irrelevance or partnership with one of these alliances. From Hamburg’s perspective, the COSCO deal makes sense, and if it didn’t take it, a rival European port would have. But at a Europe-wide level, the deal contributes to a worrying picture of COSCO’s increasing market dominance.

Back at Khalifa, I don’t manage to glimpse any PLA officials, or secret military infrastructure, though that doesn’t mean of course that the base isn’t there. But what I do see, hidden in plain sight, is a bustling Chinese-owned terminal and a park-port complex emerging exactly according to Beijing’s plans. For European shipping companies at least, that’s probably a more disturbing aspect of the Maritime Silk Road than the PLA’s project 141.