A memorial to Uyghur civil rights and the legacy of Tiananmen

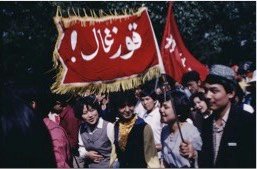

Pictured: The Uyghur student activist Örkesh, better known in English-language media as Wu’er Kaixi, raises his arms with fellow protesters in Beijing in 1989.

Protests in Xinjiang in 2009 became a watershed moment in Uyghur history. Henceforth, Uyghurs who showed any sign of civil disobedience could be categorized in one of three ways: as separatists, extremists, or terrorists. There was no more space to petition for civil rights.

Just over 30 years ago, on May 18, 1989, the Uyghur college student Örkesh Dölet (Ch: Wu’er Kaixi) sat in the Xinjiang Room of the Great Hall of the People and confronted Chinese Premier Li Peng. Like his fellow Han classmates, he spoke forcefully, criticizing Li for not responding to student demands. He beat out his words, waving his right hand to the rhythm, as he told one of the most powerful people in the country, “You are not sincere at all.”

Back then, Uyghurs committing acts of civil disobedience were not met by immediate violence, though the student protesters would be punished soon enough. Örkesh, along with the exiled poet Tahir Hamut, the novelist Perhat Tursun (who was disappeared in 2018), and other Uyghur, Kazakh, and Tibetan students, were every bit a part of the pro-democracy movement that seized Beijing in the spring of 1989. They were all demanding the freedom to access the “true meaning of life.”

Örkesh and other student leaders confront Premier Li Peng on May 18, 1989

Uyghur civil rights in 2009

Twenty years later, Uyghur students again took to the streets, this time in the capital of their “autonomous region” in Northwest China. On July 5, 2009, Uyghur college and high school students marched from their schools to Ürümchi’s People’s Square, some carrying Chinese flags, demanding that their civil rights as Chinese citizens be protected. Some of them had heard about the way Örkesh led thousands of Han students in protest decades before, but most did not know that the Beijing protest had ended in bloodshed. Like the protesters in Tiananmen, they were demanding that the government value their lives and protect their civil liberties.

The Uyghur students were responding to the Shaoguan Incident, the beatings and killing of Uyghur factory workers by Han migrant workers at a toy factory in Guangdong Province. Dozens of rural Uyghur young men who had been sent to Han-run factories as part of a coercive labor transfer program were beaten with metal rods “until they stopped moving” as they tried to hide under their bunk beds. Their bloody bodies were dragged out into the courtyards between factory dormitories as trophies, lynch-mob-style. Videos of this ethno-racial violence circulated widely on the Uyghur internet.

A widely-circulated video of Uyghurs being beaten by Han workers at the Xuri Toy Factory on June 26, 2009.

The student protesters marching in Ürümchi were met with police violence. Bedlam ensued, with Uyghur migrants destroying Han businesses in nearby neighborhoods and beating and killing more than 100 Han pedestrians. Over the next few days, Han citizens responded with mob violence against Uyghurs, and eventually armed police arrived. Hundreds, if not thousands, of people were killed or disappeared as a result of the violence. The event also laid the groundwork for a cycle of violence that produced the current mass internment of Uyghurs and creation of ubiquitous surveillance systems.

The 2009 protests were a watershed moment in Uyghur history. Henceforth, Uyghurs who showed any sign of civil disobedience could be categorized in one of three ways: as separatists, extremists, or terrorists. There was no more space to petition for civil rights.

A video of interethnic violence in a Uyghur neighborhood near the Grand Bazaar of Ürümchi, followed by video of the mass disappearance of Uyghur young men in the Heijiashan neighborhood of Ürümchi in July 2009.

As tragic as this outcome has been, a potentially more damaging aspect has been the way that solidarity between disenfranchised Uyghur and Han students or rural-to-urban migrants has been deeply fractured. Moments of social protest, such as when Örkesh, Wang Dan, Chai Ling, and other student leaders confronted Li Peng as a force unified in their demands for democracy and labor rights, now seems like something that is impossible to consider. Instead, over the past decades, state leaders have accelerated a structural antagonism between Uyghur migrant natives and Han migrant settlers in the city. This has made the economic success of Han migrants dependent on the dispossession of Uyghurs. Since the state actively recruits dispossessed Han settlers from Eastern China, blocks Uyghur migration, discourages Han dissent, and violently represses Uyghur protest, the commonalities between Uyghur and Han rural-to-urban migrants have been radically diminished.

Post-2009 social fracture

Since 2009, state policy and policing has encouraged a social fracturing centered around ethnic markers, cultural difference, and notions of progress and security. It produced a process that began to exclude Uyghurs from urban, public life and punish them for using their already limited forms of cultural expression. It began to assume their guilt as “three categories” people by virtue of their age, ethnicity, employment status, social network, and religious practice. It began to outlaw their way of life.

As a Uyghur friend who I’ll call Ablikim told me back in 2015, before he was sent to a mass internment camp:

No one knows what caused the violence in Ürümchi in 2009. There are all kinds of theories that it was organized by some centralized group or something. I think it is pretty clear to see that many people have deep anger that they can’t express. Many, like those people who live in the poor areas, are frustrated and hopeless. They can be pretty easily persuaded by other people who take advantage of that sort of anger. But in any case, what happened after 2009 did not address the real sources of the problems. It is just like 1989 or the Cultural Revolution, the leaders just say some very vague things about how things have been taken care of and now everything is harmonious. They just ignore the real problems and act like they never happened. That is a very Chinese way of doing things. They will just act as though that was in the past in another place and now those problems have been taken care of. Of course they haven’t. Those people’s lives have gone on; but for most of them they haven’t gotten any better. Most people will just see (Uyghurs in the city) and think they are bad people who aren’t willing to work or are maybe involved in some sort of crime, but the way they got to that condition was because society itself has rejected them. They didn’t really have that much choice.

Ablikim was a soft-spoken young man who always appeared nervous. His fingers shook when he spoke, a product of the psychological pressure he was under. He had been lucky enough to find a job as a teacher in a state-owned trade school despite being briefly arrested after the violence of 2009. He eventually left this job because of the way he was constantly mocked by his students and fellow teachers. They made fun of his nervous affect and his moustache. In their everyday conversations, he was the “Moustache Teacher.” Unlike Örkesh, he said he felt that his Han students and colleagues never took him seriously as a real person. “I could always see in their eyes that they were judging me. They were thinking that I wasn’t qualified for the job. I felt this the whole time.”

When I lost touch with him almost exactly two years ago in June 2017, he had begun a new job as a telecom worker, installing fiber-optic cables near his hometown. He had recently married and had a one-year-old son. For the first time over the years I had known him, he seemed happy. But the last batch of images he sent me of his son was accompanied by the message: “It’s been a long time that we did not talk, I am sorry to say I had to delete all foreigners from my WeChat friends list for security reasons.” His friends said that several months later he was disappeared.

The state now holds Uyghurs like Ablikim in camps, behind checkpoints where they are subjected to instruction in Chinese state politics, Han values, and the “national language.” Even highly educated individuals like Ablikim are subjected to this so-called vocational training. Their years of Party loyalty, Chinese language study, and cramming for college entrance exams no longer seems to matter. Instead, they are often judged guilty simply because of the appearance of their face and the ethnic category on their ID cards.

At checkpoints in Uyghur majority areas, Han people are invited to walk and drive through “green lanes.” Many Han who are native to the region think the checkpoints and camps are excessive and an inconvenience. They wish the controlled erasure of Uyghur society would cost them less. Some ally themselves with Uyghur acquaintances in small ways, helping them smuggle messages out to friends, but in most ways Han solidarity with Uyghurs has been foreclosed in the region. Kazakhs and other Muslim minorities have also been rounded up and sent to camps for the slightest hint of civil disobedience and solidarity with Uyghurs.

The end of Uyghur civil rights

In decades past, Uyghurs have attempted to intervene in Chinese policy directed toward them. In 1955, Saifuddin Azizi, the first and only Uyghur to become a provincial-level Xinjiang Party Secretary, stood up to Mao Zedong and asked him to name Xinjiang the “Uyghur autonomous region.” In 2013, Ilham Tohti, an economist at Minzu University in Beijing, wrote a series of Xinjiang policy recommendations at the request of state officials. Tohti was arrested within several months of writing these modest proposals which addressed the structural inequalities that were pervasive throughout Xinjiang life. He was charged with inciting separatism. In September 2014, he was sentenced to life in prison. The harshness of his sentence sent a chill throughout the Uyghur community. It told them that their thoughts on how the system should be reformed had now been criminalized. Civil disobedience was now considered “separatism.” Uyghurs such as Ablikim began to prepare for the worst. Three years later, the writings of Saifuddin Azizi were banned. In fact, all forms of Uyghur civic engagement that center on Uyghur survival have now been banned. In many ways, the restrictions of Uyghur autonomy cut even deeper than civil life, any attempt at epistemic disobedience is now also punished. This means that all refusals to conform to Han and secular Chinese social norms are now seen as resistance. Knowledge systems that existed prior to the arrival of Chinese settler colonialism are inherently suspicious. Embodied Islamic practice, eating only Uyghur food, speaking only Uyghur, even failure to carry a smartphone or greet officials are “micro-clues” of Uyghur “separatism.” Uyghurs must not only obey, but obey whole-heartedly.

For Uyghurs, one of high points of their civil autonomy within the Chinese system came in the Xinjiang Room in 1989 when 21-year-old Örkesh stood up to Li Peng, not as a subordinate but as his equal. Remembering the moment, Örkesh said: “We had the guts to do so because we had the truth on our side. The people liked what we said because in it they heard an expression of their own anger at the government” (my emphasis). Today, “the people” no longer seem to regard Uyghurs as engaged in an allied fight. Instead, institutionalized forms of Islamophobia have become widely accepted and Uyghurs have been placed in a state of exception, outside the law, their deaths and long prison sentences no longer counting as “rightful resistance.”

Over the past few months, Marxist Club students in Beijing have disappeared due to their advocacy for worker rights. But the same students, who are willing to suffer as accomplices in the class struggle of less-privileged Han workers, have been largely silent on the mass internment of their Uyghur and Kazakh sisters and brothers and the systematic violence of Chinese settler colonialism in Inner Asia. In China, Turkic Muslim struggles are no longer celebrated as the struggle of the oppressed. Students of Marxism who may recognize a Marxian ally in the translated writings of Frantz Fanon often seem not to recognize what the message of Wretched of the Earth might mean for Uyghurs in a Chinese context. Instead, among many Uyghur culture and society have come to be treated as valueless.

These are the reasons why non-Chinese allies and accomplices in the fight for human dignity must continue to mainstream Uyghur and Kazakh stories. Chinese allies outside of China must continue to organize against Islamophobia and other new forms of racism. All of us must remember that 30 years ago in Tiananmen Square, Uyghurs were regarded as equals in the struggle for human flourishing.

Darren Byler’s Xinjiang Column is published on the first Wednesday of every month. Previously:

‘Truth hidden in the dark’: Chinese international student responses to Xinjiang