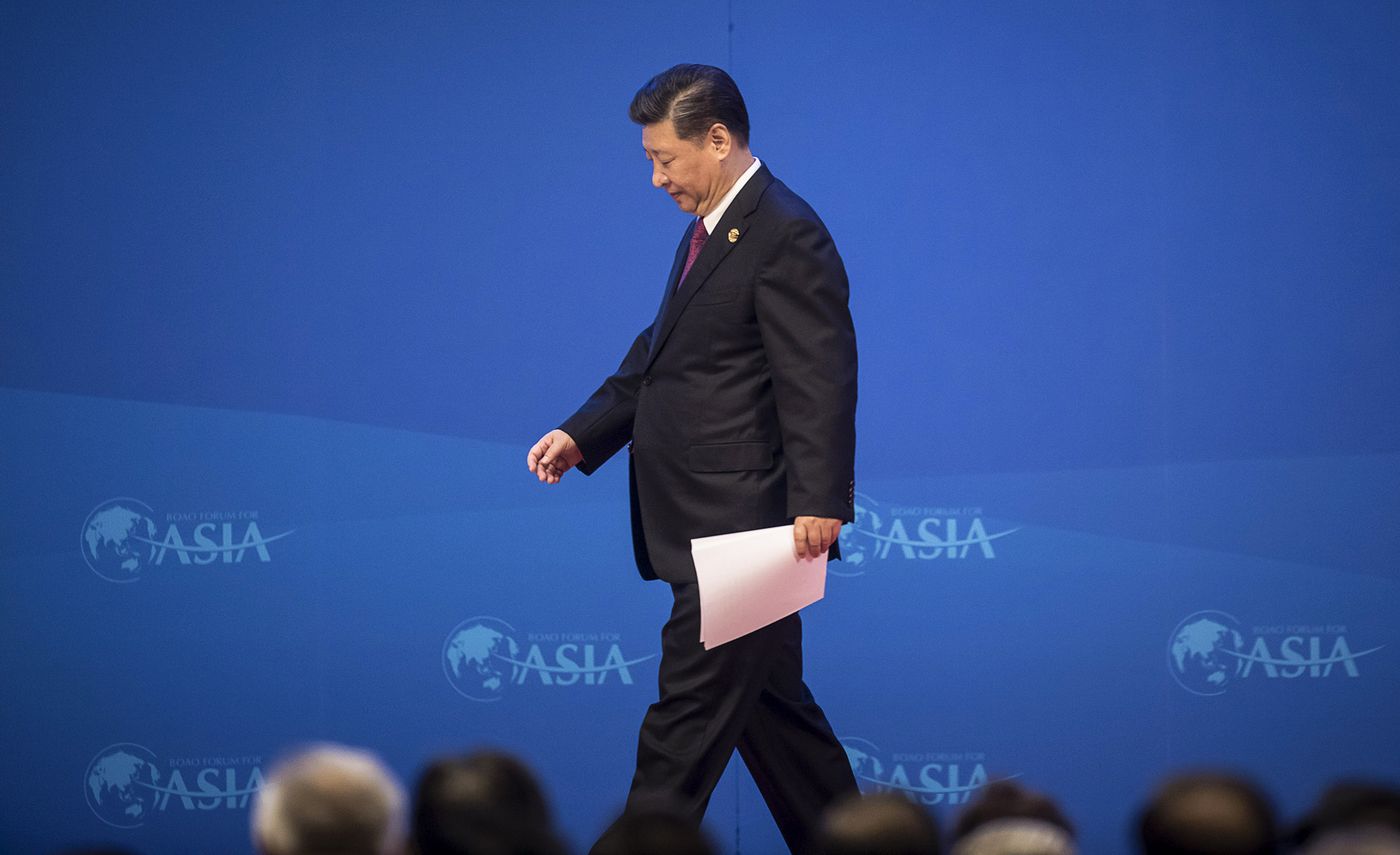

The hard choices facing Xi Jinping

Here are two different pictures of the world facing Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 by two highly respected analysts of elite Party politics:

Xi is facing unpalatable choices between hardline and conciliatory responses to the U.S. trade war and the Hong Kong protests, argues Minxin Pei in the Nikkei Asian Review. “So far it is hard to tell which direction Xi is leaning. But one thing is sure: he doesn’t have much time.”

China’s political calendar demands a quick resolution. October 1 this year is the 70th anniversary of the founding the People’s Republic. Xi obviously would like to showcase the country’s achievements under his leadership in the last seven years. The failure to end the Sino-American trade war or defuse the Hong Kong crisis will not only dampen the festivities, but also raise fresh doubts about his leadership.

Pei also notes:

While moderates in the party would like Xi not only to make the necessary compromises to get over the twin crises but also start retreating from policies that have contributed to the deterioration of U.S.-China relations, they are unlikely to have the strongman’s ear. Power has been so concentrated under Xi that only a few loyalists now have access to him. Since such people are afraid to offer advice that implies Xi’s fallibility or damages his authority, their safest bet is to tailor their recommendations to the options they believe he prefers.

“The backlash abroad against President Xi Jinping’s China, at least in developed nations, has spread rapidly in the last year,” argues Richard McGregor on CNN, adding that “Beijing’s opaque internal political system means it is hard to make judgments about domestic Chinese politics, but there can be little doubt that a backlash is underway at home, too.”

Xi’s enemies are finding their voice, McGregor writes.

As a leader, Xi is unique in post-revolutionary party politics in not having any identifiable domestic rival or successor, largely because he has ensured that none have been allowed to emerge. But Xi has earned himself an array of what we might called “bad enemies” and “good enemies” since taking office in late 2012.

They range from the once-rich and powerful families he destroyed in his anti-corruption campaign, all the way to the smaller reformers angered by his illiberal rollback of the incremental institutional advances of the reform period.

Forced to lay low initially because of the dangers of challenging him outright, Xi’s critics at home have begun to find their voice. They have been outspoken mainly on economic policy, but the deeper undercurrents of their criticisms are unmistakeable.

The sons of former top leaders, revered scholars who guided China’s economic miracle, frustrated private entrepreneurs and academics furious about Xi’s unrelenting hardline — all have complained in multiple public forums, in speeches, in online postings and in widely circulated essays at home and offshore, about Xi’s policies and style.

One of those academics who has “widely circulated essays at home” is Xǔ Zhāngrùn 許章潤, who Prospect magazine just selected as one of its “top thinkers” of the world for 2019.

If Xu Zhangrun worried that his essays published earlier this year criticizing China’s repression under Xi Jinping might not cause a stir, the Chinese state helpfully ensured they received the prominence they deserved: Xu was suspended from his post at Beijing’s Tsinghua University and barred from leaving the country. In the past year Xi has entrenched his power, including the scrapping of presidential term limits. Xu warned that Xi’s moves had “nullified more than 30 years of reform and opening up and slapped China back to the scary era of Mao.” Especially after the state’s reaction, Xu’s critique has struck a chord.

For translations of Xu’s work, see China Heritage.