China’s Dirty Web

You’ve likely not heard of Zhina Wiki, Esu Wiki, or a slew of other 4chan-like forums in China that were recently forced to shut down. These were virtual meeting places for some of the country’s worst online citizens, characterized by harassment and rampant doxing (most notoriously of the science fiction author Liu Cixin). As one of the Esu group mottos went: “To be evil and vulgar is to be righteous.”

Illustration by Anna Vignet

Two Chinese websites notorious for memes, doxing, and harassment have recently been shuttered by authorities in what appears to be a coordinated crackdown.

The sites — Zhina Wiki (支纳维基 Zhīnà Wéijī) and Esu Wiki (恶俗维基 Èsú Wéijī) — won’t be missed, at least by the many people who have seen their personal information, private correspondences, nude photographs, and anonymous message board posts made public on those platforms, nor will they be missed by the state’s internet monitors, who were occasionally the target of posts on the clownishly anti-Party Zhina.

News spread on October 28 of the arrest of several young Chinese netizens. Esu Wiki 恶俗维基 was cited by name in reporting, including in a now-deleted post on The Beijing News’s website headlined, “15-year-old male in Chengde, Hebei ordered by Public Security officials to undergo criticism and education for multiple visits to anti-China website” (河北承德15岁男生多次上网浏览反华信息被公安批评教育 Héběi Chéngdé 15 suì nánshēng duōcì shàngwǎng liúlǎn fǎnhuá xìnxī bèi Gōng’ān pīpíng jiàoyù).

What kind of content, exactly, were these sites serving up to warrant a multi-agency strike campaign? What kind of people were behind these sites, and what were their motivations?

Rather than a black-and-white parable of censorship and top-down direction of online political struggles, we have a more confusing set of stories: strict state controls on the internet running up against Wild West commercialization, the shaky collusion between the state security apparatus and a small group of tech companies building a massive reservoir of data that neither side can seem to keep secure, grassroots nationalists who flout the law to carry out online political campaigns, and the proliferation of groups that challenge the leadership of the Party but also reject liberal democracy.

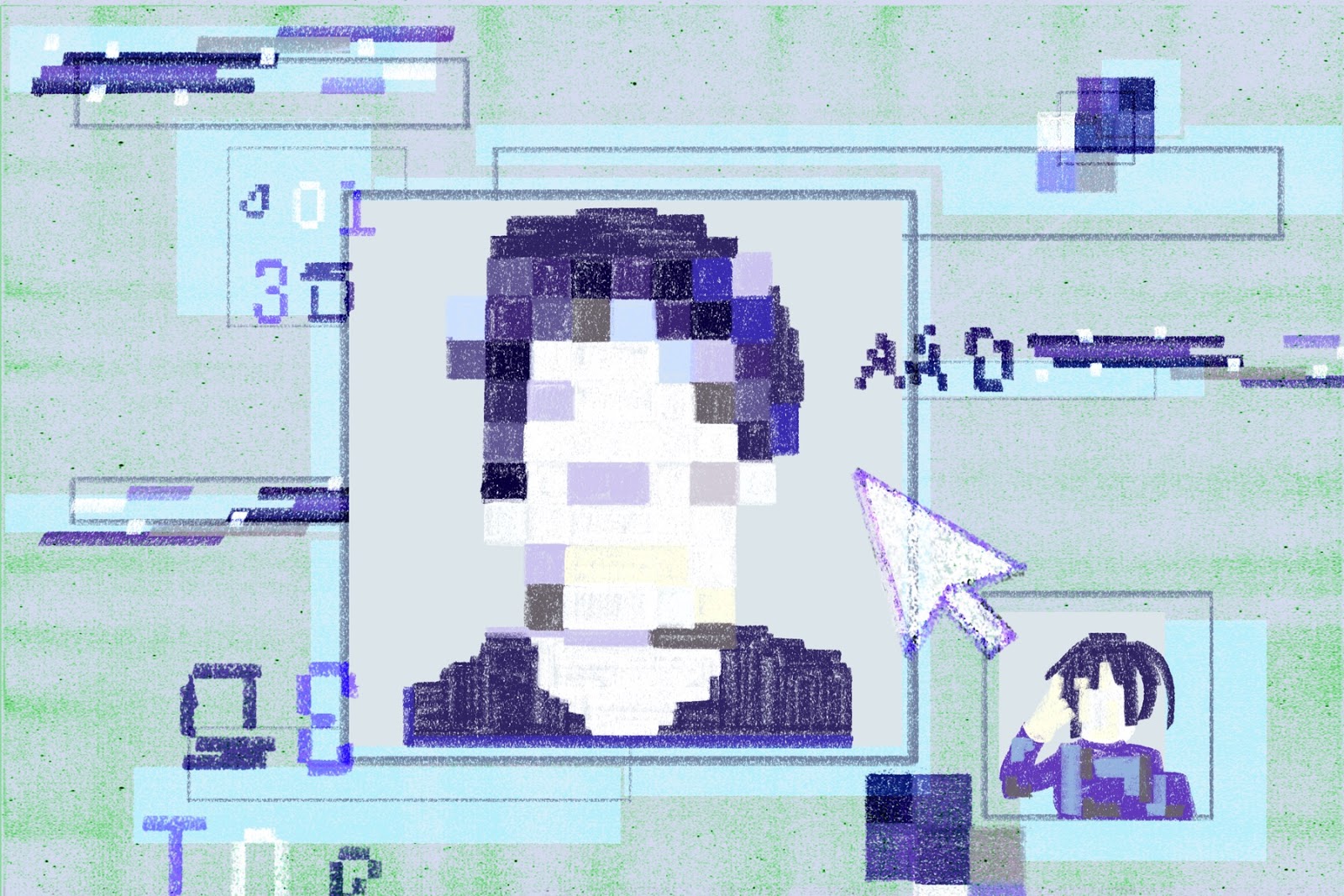

The two wiki-based sites, Zhina Wiki and Esu Wiki — and sister sites such as EXOZ Star Wiki (EXOZ明星维基 míngxīng wéijī) and Esu Gou Wiki (恶俗狗维基 èsúgǒu wéijī) — were conceived as something of an Encyclopedia Dramatica for the Chinese internet, a wiki for internet subcultures, memes, and web celebrities. But they grew into something far darker, taking advantage of lax corporate and government data security to furnish materials for doxing and harassment campaigns.

Esu Wiki, the first of the two sites to appear, grew from the popular Di Bar 帝吧 (dìbā) subforum on the Bǎidù Tiēba 百度贴吧 message board. Originally a forum to circulate memes about footballer Li Yi, it became a hotbed of aggressive memeing and Chinese nationalism.

The chūzhēng biǎoqíng 出征表情, or “battle memes,” of Di Bar might have gotten spicy at times, but the targets, which have included Taiwan sovereigntists and pop stars, were considered fair game. Content was otherwise relatively wholesome, often nationalistic, or arcane enough that nobody got their feelings hurt.

A cadre of Di Bar users known for èsú míyīn 恶俗迷因 (literally: evil and vulgar memes) often ventured into unacceptable territory — mostly political but not always — at least as adjudicated by Tieba users or administrators. Sometimes their targets were fellow users. Esu Wiki was created as a place to store their memes and keep track of targets of harassment.

The vile and vulgar memes of Di Bar and its offshoots will be familiar to readers of chan site imageboards, whether the Japanese originator 2ch or its Western copycats, 4chan and 8chan. Both make use of much of the same source material, too, relying heavily on manga, fascist imagery, and erotic fan art.

I asked an Esu contributor for the quintessential Esu meme, and her reply: Gong poems (龚诗 gōng shī) — doggerels written in a cod classical style that are basically incomprehensible.

Opaque to outsiders, hilarious to insiders, open to infinite modification, with origins in a harassment campaign: Indeed, the Gong poem has it all. Here’s an example of what it looks like:

Written by Esu users and attributed to a previous target of online harassment (the first two characters of his name, Gōng Shīfēng 龚诗峰, are “Gong poem”), deep knowledge of obscure slang and intertextual allusion is required to decode these “poems” — if decoding them is even possible, since a key element is attempting to pull meaning out of what seems to be nonsense.

Another early Esu contributor told me that Esu Wiki attracted a number of outcasts from other online communities, such as Liu Zhongjing fans, or people known as Yífěn 姨粉, followers of a radical online figure who prophesies a Great Flood that will lead to the de-Sinification of China and its replacement by dozens of smaller ethnostates. They were looking for harder stuff than boards like Di Bar could provide (Esu also hosted its own message boards). Since Esu Wiki was hosted outside of China and usually blocked on the mainland, it operated without the censorship that Di Bar was bound by and attracted users that were comfortable jumping the Great Firewall, or who had physically jumped the wall (a useful term: ròushēn fānqiáng 肉身翻墙, to physically make the leap outside of mainland control, rather than merely VPNing through).

With minimal restrictions on content and a new breed of user, it wasn’t long before Esu Wiki became a battleground for not only gleeful shitposting and memeing, but also for settling internecine feuds with humiliating doxing and humiliation campaigns.

Here, state power and the commercialization of the internet come together: Internet companies in China are collecting vast amounts of data, and much of that data ends up being handed over to the government.

Doxing is a tradition that goes back to at least the 18th century, when Voltaire made public Rousseau’s abandonment of his children, and was a common feature of early internet Usenet and IRC feuds.

The tradition continues: the Gamergate backlash against Depression Quest developer Zoë Quinn climaxed with threats and doxing before spilling over to include doxing and harassment of various sideline characters, like indie developer Phil Fish, who had stirred controversy by calling Gamergaters on 4chan “essentially rapists.” In another recent incident, 8chan, a message board notable for having fans among a series of mass shooters, doxed a federal judge. And entire communities, like Kiwi Farms, thrive on what often approaches the doxing of what they call “lolcows,” eccentric online personalities who can be “‘milked’ for amusement and laughs.”

Doxing takes on a different character in China, and consequences can be more severe.

Christian Weston Chandler has an entire wiki-based site dedicated to his eccentric behavior, but he is in no danger of being dumped in a black cell for posting videos of himself drinking semen and Fanta. True internet outlaws like Fredrick Brennan, founder of 8chan, and Andrew Anglin of the Daily Stormer keep a low profile (whereabouts of both men is currently unknown), but both are fairly sure that they will never be softened up in a tiger chair before giving a televised confession, a fate that has befallen even mild critics of the Chinese state.

Maintaining anonymity in China is far more difficult than it is in the West.

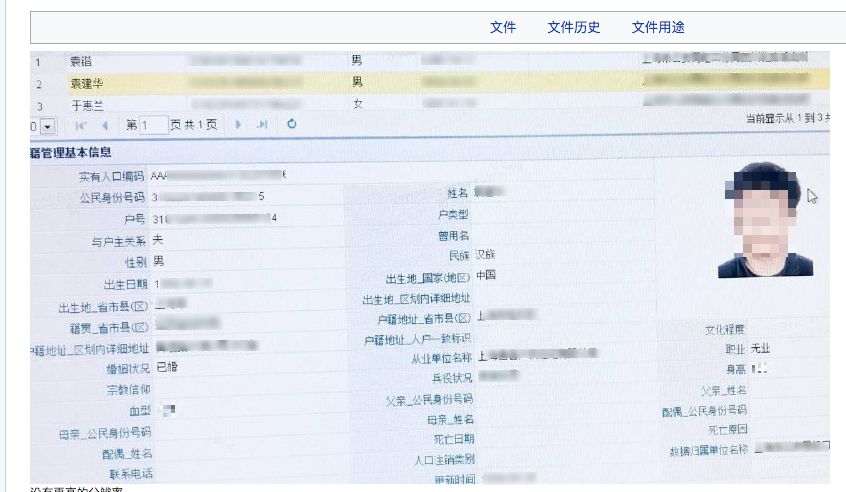

The Chinese internet is a privacy nightmare. The real-name registration system, or shímíngzhì 实名制, was intended to civilize the Chinese internet, but it adds to the amount of data floating around in the backend of websites. The existence of centralized government databases, which hold identification cards and easily verifiable serial numbers and links to other data, makes it all the simpler to unravel the anonymity of netizens. Here, state power and the commercialization of the internet come together: Internet companies in China are collecting vast amounts of data, and much of that data ends up being handed over to the government.

The massive stores of data combined with loose regulations on data security mean that government agencies often have hackers reading chat logs over their shoulders. A 2016 report by Citizen Lab, for example, showed that Baidu software was leaving unencrypted personal data exposed. Just this year, unsecured servers opened up half a billion job-seekers’ resumes and e-commerce records to the open internet, and a database put together by state surveillance leaked online, making public “hundreds of millions of chat logs.”

Strict internet controls makes it, paradoxically, easier for truly vile content to exist on the Chinese internet. A Chinese porn site, for instance, since it is already outlawed, does not have much incentive to self-censor content such as photos of sexual assault or child pornography; a QQ group selling unapproved dietary pills does not have much incentive to crack down on vendors moving substituted cathinones or human growth hormone; and if a group is trading credit cards, there’s no particular reason they would turn their nose up at a leaked database from a local Public Security Bureau branch.

Zhāng Dōngníng 张冬宁, the spiritually Japanese cartoonist who was detained for her satirical drawings of a China inhabited by anthropomorphic pigs, is a good case study of the thorough doxings that sites like Zhina and Esu carry out, and the harsh consequences for exposure. Western media coverage seemed to suggest that she had run afoul of authorities because of her artistic output, but she was deeply involved with online subcultures that play out internecine beefs across the axis of wiki-based sites. Her Zhina entry exposed reams of chat logs, a collection of nude images, and speculation that she had made a living with sex work, and went in-depth on her links to Chinese right-wing reactionary elements online.

While sites like Encyclopedia Dramatica and Kiwi Farms operate legally and can be policed by libel law and the threat of lawsuits, sites like Zhina operated outside the reach of law.

The loss of anonymity had dire consequences for Zhang. With no updates since her arrest, it is likely that she is still being held in a detention facility. The “elegant gentlemen” (高雅人士 gāoyǎ rénshì), as the site’s hackers call themselves, likely exploited lax privacy at web companies or leaked databases from government agencies to obtain Zhang’s information.

Zhina Wiki, a very similar meme site and the source of the Zhang Dongning doxing, split from the Esu Wiki community over a previous incident of doxing that was seen as too extreme.

The target of that doxing was none other than Liú Cíxīn 刘慈欣, author of The Three-Body Problem, subject of a New Yorker profile and a personal favorite of Barack Obama.

In May of this year, Liu fell afoul of the “elegant gentlemen,” possibly the result of a disagreement among sci-fi fans. In what became known as the Liu Cixin Incident (刘慈欣事件 Liú Cíxīn shìjiàn), the writer’s ID and phone numbers were leaked, his xiǎohào 小号 (a subsidiary account or “alt”) was uncovered, and his formerly anonymous posts on Baidu Tieba were collected on Esu Wiki.

In a response to a post that originally appeared on the Zhihu 知乎 message board — “What do you think of Esu Wiki doxing Liu Cixin?” (如何看待刘慈欣被恶俗维基扒黑料 rúhé kàndài Liú Cíxīn bèi èsú wéijī bā hēi liào) — a lengthy reply (saved on Esu Gou) warned of potential consequences. The anonymous commenter echoed a sentiment voiced by Esu users — “To be evil and vulgar is to be righteous” (恶俗是正义 è sú shì zhèngyì) — but, the anonymous commenter argued, there was nothing righteous in the doxing of Liu Cixin.

An editorial in the Beijing Evening News (刘慈欣被曝隐私,网争勿用“黑暗森林法则” Liú Cíxīn bèipù yǐnsī, wǎng zhēng wù yòng “hēi’àn sēnlín fǎzé”) brought Esu to a wider audience and echoed those same warnings. The editorial managed to both dox Liu to the greater public while also ruminating on the need for a legal campaign against the hackers responsible.

In the same month that Liu’s Tieba posts were leaked, Tieba administrators locked access to all posts made on the site before January 2017, cutting off the potential for future mining of Tieba content by Esu users.

Zhina, as its name — a variation on a derogatory name for China — and frontpage featuring images of Xi Jinping as Hitler might suggest, is the most explicitly anti-establishment site.

The often indecipherable nature of Esu memes and purposely obfuscatory argot can make this tough territory for an outsider to get their bearings in, and any attempt to recount a comprehensive history of Zhina and Esu would require volumes — the dramatis personæ alone would outstrip the word count of this piece. (I’ve already left out dozens of related phenomena like Red Bank [红岸 hóng àn], and the reader has been spared biographies of figures like Master Ci 磁大师.) The internal politics of Esu and Zhina are as tough a nut to crack as their ideological leanings.

Doxing and harassment on Esu and Zhina was often about simply settling scores and attacking web community rivals, but there were sometimes deeper political motives at play. Di Bar’s orientation is nationalistic and generally supportive of the state and Party, but Esu and Zhina are less homogenous.

Both Zhina and Esu played host to apolitical shitposters and tricksters, as well as devotees of various extremist subcultures. Those subcultures included those that Chenchen Zhang has connected to a global right-wing populist discourse, fed by and feeding back into sister communities on 8chan and 2ch, but also more esoteric sects like Liu Zhongjing fans and the spiritually Japanese.

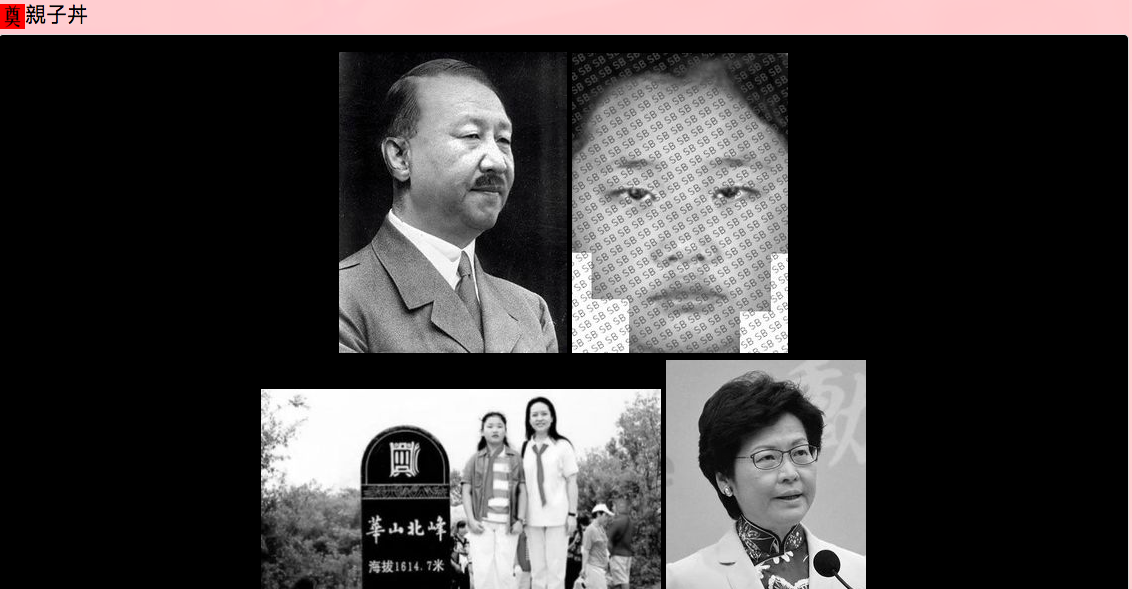

Zhina, as its name — a variation on a derogatory name for China — and frontpage featuring images of Xi Jinping as Hitler might suggest, is the most explicitly anti-establishment site. Doxing online figures remained the bread and butter of Zhina up until its disappearance, but it also hosted private materials on top leaders, a mirror of the Panama Papers, and a guide to Party princelings.

The coordinated doxing clearly violated Chinese law, which was toughened up following a crackdown on internet vigilantism and “human flesh searches” (rénròu sōusuǒ 人肉搜索) in the mid-2000s.

But the political content couldn’t have sat well with internet monitors, either.

An announcement on Zhina explained:

“Just as we expected, the Ministry of Public Security, under the leadership of a special investigations team from the Ministry of State Security, hoping to crack Chairman Winnie’s list of revolutionary heroes, have launched an overwhelming attack. Our humble website was formerly meant as simply a minor amusement, but because of the outrageous actions and regressive policies of the criminals in power, it has been forced to change its orientation.”

(不出所料,公安部、国安局专案组督办下,破站荣登维尼的红色清单,速度之快,真是让人受宠若惊嗷~寒舍最初是一个小型网络娱乐中心,在贵匪的一系列胡作非为和逆行倒施下,自发进行了转型。)

On October 17, Zhina and Esu began showing 503 Service Unavailable and 500 Internal Server errors. All alternate domains were unavailable. A former Zhina domain, zhina.red, redirected to a page operated by the Thailand Computer Emergency Response Team. They were scrubbed from the internet, almost simultaneously.

Zhina and Esu both changed domains and hosts frequently, and were only intermittently available behind the Great Firewall. They made use of Cloudflare’s services (the company has previously pulled support from sites like the Daily Stormer and 8chan after backlash on social media).

The website hosts were in Southeast Asia or Eastern Europe. As with other Chinese-speaking online reactionary communities, many of the contributors lived — or claimed to live — overseas. Speculation from a source close to Zhina suggested that several of the sites’ administrators were already under arrest.

Rumors about the fate of founders and editors have mostly been relegated to Esu Gou, the only site remaining (and, perhaps not coincidentally, a site seen as pro-establishment and not yet blocked in the mainland), where rumors about the story’s imminent breaking in mainstream media are rampant.

Speculation has also spilled over to other sites, like the post above from a Bilibili user, suggesting that there has been a handover to authorities of all user data from Zhina and Esu. Both sites took QQ numbers from members, a real-name registration system writ small, hoping to insure against editors using the site for personal gain.

Some answers recently surfaced, when arrests began to be made. Deutsche Welle’s Chinese-language website began reporting on “more than a dozen young Chinese netizens questioned or detained for visiting ‘anti-China’ websites.” Once again, Esu Wiki was directly named. DW cited the Hebei case, but also recent reports of similar cases in Xiamen, Fujian Province, and Liuzhou in Guangxi.

It seems increasingly clear that the crackdown on Zhina and Esu was a coordinated effort across multiple agencies, ranging from Ministry of State Security officials, who would be able to coordinate the seizure of domains in foreign states (official reports quoted by DW make reference to “servers located overseas”), right down to local Public Security Bureau officers in third-tier cities.

Sima Nan 司马南, a popular online intellectual and prominent New Left figure, took to Weibo following news of the arrest of the young man in Hebei, questioning the decision to arrest someone for “browsing” content that went against the Party line.

“How many people you going to grab?” he asked, in a post that quickly went viral.

It is unclear whether or not Sima Nan is familiar with the content on Esu and similar sites, and the larger issues with their use of material gained illegally.

In its coverage, Epoch Times described Esu as “a platform that exposes bad behavior by notable or famous Chinese figures,” and the detention of users as an “intensification in the Chinese regime’s efforts to crack down on internet speech.” Much of the material on Esu and Zhina, including direct threats against individuals and groups, and underage nudity, would be unlawful in many jurisdictions, including the United States, and rather than an intensification, the crackdown seems to have been carried out with less ferocity than one executed earlier this year against porn sites, which saw 17 arrests in multiple provinces.

But even those more familiar with the sites seem interested in lionizing the “elegant gentlemen” of Esu. A commentator by the name of Sister Swift (雨燕姐姐 yǔyàn jiějiě), before the arrests, wrote a piece called, “Who is commemorating the May Fourth Movement? Whose May Fourth Movement are we commemorating?” (谁在纪念五四?纪念谁的五四? shéi zài jìniàn wǔsì? jìniàn shéi de wǔsì?). She included Esu’s hackers on a short list of “true heroes” that included Julian Assange and Edward Snowden.