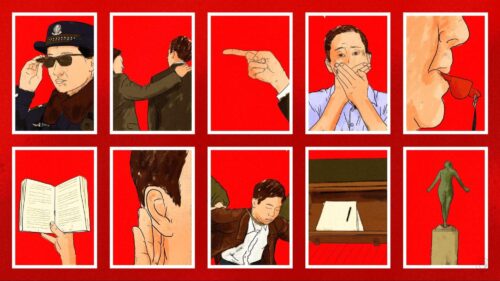

Feroza Aziz and TikTok’s censorship problem

TikTok — the short-video app owned by a Chinese company that has become popular among young Americans — has been the subject of growing scrutiny in the U.S. for several months, but this month, action began in Washington, D.C.

At the beginning of November, the U.S. government announced a national security investigation into Beijing-based Bytedance, the parent company. Bytedance’s investors, including Sequoia Capital and SoftBank, view growth in the U.S. as key to achieving their goal of an initial public offering late next year, so the company began a public relations campaign.

“No, TikTok does not censor videos that displease China,” Alex Zhu (朱骏 Zhū Jùn), head of TikTok, told the New York Times (porous paywall). “And no, it does not share user data with China, or even with its Beijing-based parent company. And even if the Chinese leader Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 himself asked the company to censor or hand over data, Zhu said, ‘I would turn him down.’”

It’s simply not credible for a Chinese company that wants to survive in the People’s Republic to refuse a direct order from Xi, who must be obeyed, we noted earlier this week. As one “former employee in TikTok’s Los Angeles office” told the Wall Street Journal (paywall): “We’re a Chinese company,” this person said. “We answer to China.”

And now this, the saga of 17-year-old Feroza Aziz, who originally posted the following video about China’s treatments of Uyghurs in Xinjiang on her TikTok account:

Here is a trick to getting longer lashes! #tiktok #muslim #muslimmemes #islam pic.twitter.com/r0JR0HrXbm

— Feroza Aziz (@ferozaazizz) November 25, 2019

She was unable to access her account soon after.

TikTok’s director of creator community Kudzi Chikumbu on Tuesday echoed the words of his chief in an interview with…CNBC’s Closing Bell.

“We don’t remove content based on sensitivities around China or other governments,”

As he appeared on the show, the Washington Post reported that a 17-year-old user in New Jersey, Feroza Aziz, was locked out of her account after she posted a viral video criticizing the Chinese government’s treatment of the Uyghur ethnic minority.

After several media reports on Aziz, including by the New York Times (porous paywall), she tweeted: “UPDATE: my tik tok is back up…very suspicious.”

UPDATE: my tik tok is back up…very suspicious

— Feroza Aziz (@ferozaazizz) November 27, 2019

What will TikTok do next?

Reuters says that Bytedance is seeking to “ringfence its TikTok app” so that it can run independently from the parent company’s operations in China. According to Reuters’ sources:

- Bytedance “completed the separation of TikTok’s product and business development, marketing and legal teams from those of its Chinese social media app Douyin in the third quarter of this year… During the summer, it also hired an external consultant to carry out audits on the integrity of the personal data it stores.”

- TikTok says its user data is stored “entirely in the United States, with a backup in Singapore. It has also said that the Chinese government does not have any jurisdiction over TikTok content.”

- There is a new push in Mountain View, California, for TikTok to set up a team that will “oversee data management [and] determine whether Chinese-based engineers should have access to TikTok’s database, and monitor their activity.”

- “TikTok is also hiring more U.S. engineers to reduce its reliance on staff in China… TikTok employs about 400 people in the United States,” and about 50,000 worldwide.

What about WeChat, the elephant in the room?

In our January Red Paper, we suggested that it was only a matter of time before WeChat, the messaging-and-everything-else app from Tencent, drew the attention of American lawmakers and activists for censorship or something else. That hasn’t really happened yet, but there has been a steady trickle of media reports.

Here is the latest report on WeChat censorship, from the Verge, which cites a Texas resident whose WeChat account was shut down for posting about the Hong Kong elections, which prompted him to join a “WhatsApp group for Chinese Americans who’ve recently been censored on WeChat.” This was Tencent’s explanation:

In a statement emailed to The Verge, a Tencent spokesperson said, “Tencent operates in a complex regulatory environment, both in China and elsewhere. Like any global company, a core tenant [sic] is that we comply with local laws and regulations in the markets where we operate.”

The company emphasized that WeChat and Weixin are separate apps with separate rules. “If you register with a Chinese mobile number (+86), you will be using Wēixìn [微信], the version for Chinese users. If you register by any other method you will be using WeChat, the version for international users. Weixin and WeChat use different servers, with data stored in different locations. WeChat’s servers are outside of China and not subject to Chinese law, while Weixin’s servers are in China and subject to Chinese law.”

We can expect that statement to be tested frequently in the coming months. WeChat is also bound to come under scrutiny for misinformation about the 2020 American elections, which will, no doubt, spread like the common cold on WeChat groups run by U.S. residents.