‘They screamed like babies’: Uyghur prisoner describes abuse in Xinjiang

In one of the most detailed accounts from a Uyghur prisoner in Xinjiang to date, the fashion model Merdan Ghappar leaked video and text describing his detention, including instances of torture that he witnessed. Ghappar’s account shows that even well-integrated Uyghurs are being targeted, and that arbitrary detentions have continued into 2020.

Merdan Ghappar (Màiěrdān Āba 麦尔丹∙ 阿吧) was, until January of this year, living in the southern Chinese metropolis of Guangzhou. A successful Uyghur fashion model, fluent in Chinese and well integrated into society, he had so far been spared targeting by the state’s mass detention and coercive assimilation program for Uyghurs that has been ongoing since 2017.

Then, like so many other Uyghurs, he received a call to return to his home in Xinjiang. The BBC reports:

…police knocked on his door, telling him he needed to return to Xinjiang to complete a routine registration procedure.

The BBC has seen evidence that appears to show he was not suspected of any further offence, with authorities simply stating that “he may need to do a few days of education at his local community” — a euphemism for the camps.

On January 15 this year, his friends and family were allowed to bring warm clothes and his phone to the airport, before he was put on a flight from Foshan and escorted by two officers back to his home city of Kucha in Xinjiang.

Ghappar was detained, but managed to leak out evidence of his treatment and the abuse of fellow prisoners that he witnessed. It is one of the most detailed accounts from a Uyghur prisoner in Xinjiang to date.

- Ghappar’s extensive written account, sent as one long text message to a relative in Europe, has been translated in full by the scholar James Millward. It contains horrifying details of crowded prison cells — even as COVID-19 spread into the Xinjiang region — as well as instances of torture that he witnessed. One in particular stands out:

In the evening, another four people came in, the youngest 16 and the oldest 20. The facts of their case were that during the epidemic period, they were outside playing a kind of game like baseball. In the evening they were brought to the police station and beaten until they screamed like babies. The skin on their buttocks split open, they couldn’t sit down.

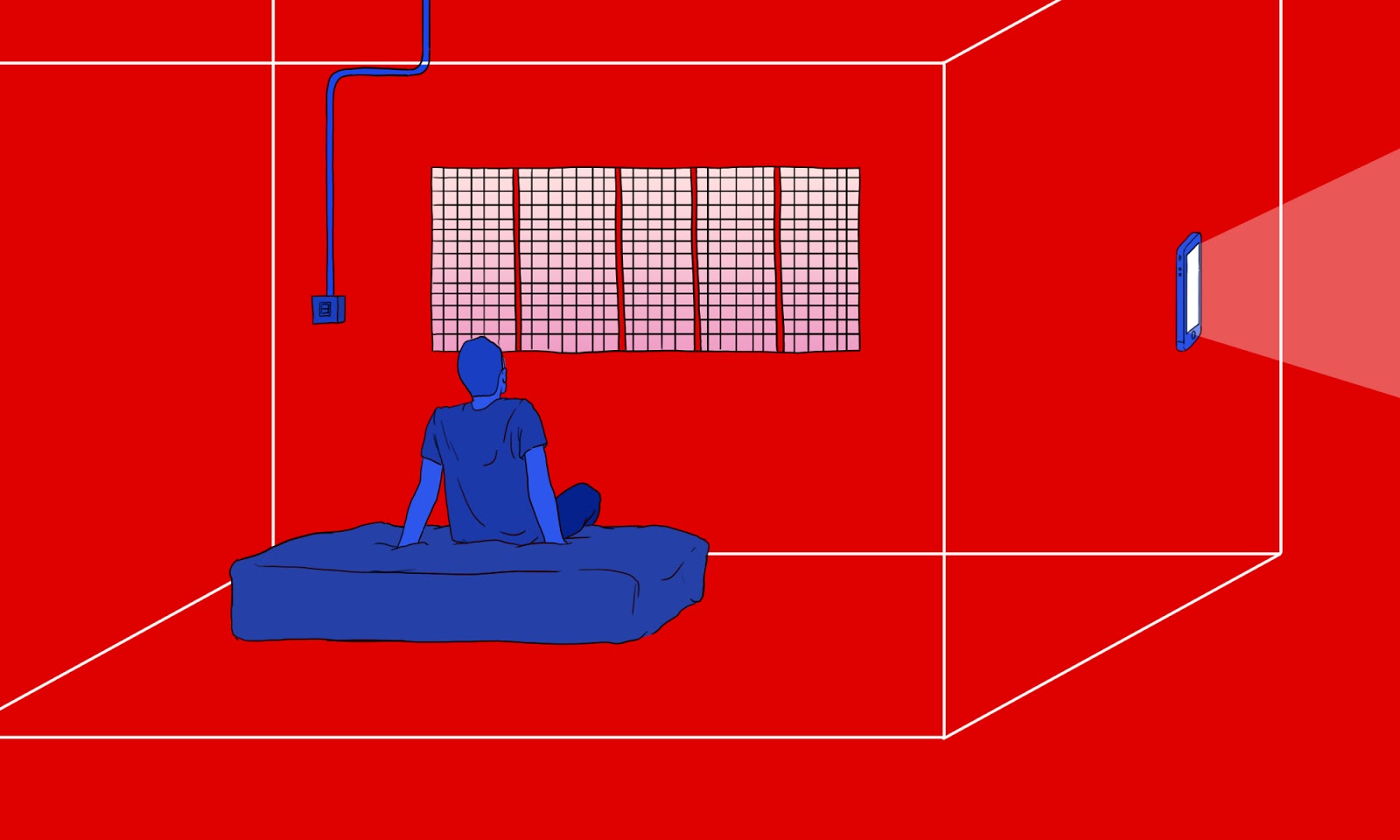

- Ghappar also filmed himself in a quarantine cell, where he is seen with his wrist shackled to a bed while propaganda blasts over loudspeakers. The Globe and Mail verified details in Ghappar’s account:

Mr. Ghappar’s account, jointly reported with the BBC, is based on interviews with the man’s family and friends, as well as their documentation of what they learned as they sought to understand what happened to him. Social-media accounts belonging to Mr. Ghappar and a modelling agency validate additional elements of his account, as does a digital court record.

Identifiable buildings in video sent by Mr. Ghappar match buildings in Kucha, where he says he was taken — and where police told his family that he was being held in quarantine. A document Mr. Ghappar photographed and sent to his family also includes the name of the neighbourhood in that location — and includes previously unknown details about a sweeping local campaign that required self-confession of what the state considers wrongdoings from children as young as 13.

What does Ghappar’s account tell us? Per James Millward, there are two key takeaways:

- Even well-integrated Uyghurs are targeted: “Despite official P.R.C. claims that its mass detention of Uyghurs and other non-Han people is meant to steer uneducated farmers away from extremist thinking by teaching them Chinese, Merdan clearly enjoys native fluency in Chinese and was successfully employed in Guangzhou before being taken back to detention in Xinjiang.”

- The arbitrary detentions still haven’t stopped: “His account also shows that the practice of ‘rounding up everyone who should be rounded up’ — a mandate under which Xinjiang authorities have especially targeted professionals and Uyghurs with contacts abroad — was still going on in 2020, despite the coronavirus pandemic and despite P.R.C. claims that internees have ‘graduated’ to work in labor gangs assigned to Xinjiang and eastern Chinese factories.”