Why Chinese viewers hate Disney’s ‘Mulan’

As Hong Kong activists solicit worldwide solidarity for the #BoycottMulan movement and Disney faces growing criticism for shooting much of the movie in Xinjiang, Chinese moviegoers have found different reasons to tear the movie apart.

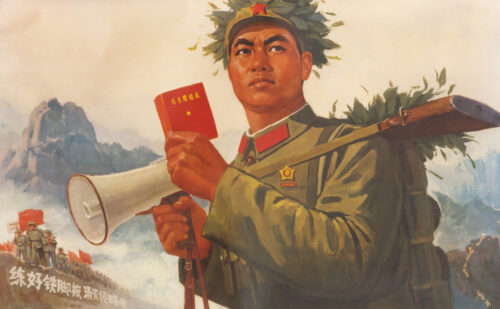

As Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 once said, “We should support whatever the enemy opposes, and oppose whatever the enemy supports.” Chinese viewers of Mulan (2020), however, seemed to have forgotten about this commandment: As Hong Kong activists solicit worldwide solidarity for the #BoycottMulan movement and Disney faces growing criticism for shooting much of the movie in Xinjiang, there is no helping hand from China. Instead, Chinese moviegoers have found different reasons to tear the movie apart.

Despite fielding a cast of A-list Chinese stars, Mulan’s live-action remake currently has a horrid 4.7 on Douban (China’s IMDb), significantly worse than the 1998 original’s 7.8, and even lower than the notorious The Great Wall’s 4.9. The all-Asian cast, most scenes being shot in China, and the expensive royal palace background sets: None of these hit it home for the Chinese audience.

One review (in Chinese) compared the incorporation of “authentic” Chinese cultural elements into the movie with “the taste of General Tso’s Chicken”: “It is cooked in a wok and served with chopsticks, but that doesn’t make it Chinese food… Under the coat of Chinese culture, Mulan presents the inherently American narrative that you can overcome anything in the world by being yourself. It uses our culture as the medium to convey their values. If you change every ‘qi’ to ‘force’ and ‘Mulan’ to ‘the Chosen one,’ you will get a perfect remake of Star Wars: The Force Awakens.” In particular, the movie’s refrain “I will bring honor to us all” struck this viewer as more reminiscent of “the individualistic heroism of chivalry” than the Chinese takeaway of “sacrifice yourself, enlist for your father, and serve your country.”

Wáng Xiāo 王骁, an agitator from the nationalist website Guancha.cn, suggested on Weibo (in Chinese) that Disney had usurped China’s “discursive power,” or “the power to interpret our own culture.” This resonated with many viewers, who were angered by the movie’s presentation of “a Western understanding of Chinese culture as conservative values (of feudal piety), failing to realize that many of these values have since been abandoned by the Chinese people. It just wants to look Chinese enough to fool the Western audience.” A particularly nationalistic comment tried to relate this to Sino-American tension: “With a supposedly all-Asian cast that conveniently has no PRC nationals, Mulan is yet another one of the West’s attempt to vilify and fetishize China.”

The Chinese audience found it hard to relate to a depiction that boasts of its cultural authenticity while being rife with jarring historical mistakes. Many were bewildered when they saw the Hua family living in a tulou — a bagel-shaped structure featuring mud walls and a courtyard in the middle, typically found in Hakka communities in Fujian. Its appearance does not make any historical sense because Mulan is set in the period of the Northern and Southern dynasties, and there is no way that the Northern Wei (A.D. 386–534) emperor could conscript someone from the other end of the country. It is also anachronistic: Tulou only became commonplace nearly a millennium after Mulan’s setting.

The movie also suffers from painfully out-of-place references to the archetypal Ballad of Mulan, the poem on which subsequent versions of the story are based. Mulan’s opening scene with the two rabbits was a direct homage to the Ballad’s concluding couplets:

But when the two rabbits run side by side,

Can you really discern whether I am a he or a she?

The allusion, however, strikes the Chinese audience as facetious. Accented Cinema, a Chinese YouTuber who does commentary on Chinese movies, accused this scene of “blatantly virtue signaling,” as it “took one of the most iconic and powerful lines from the poem and turned it into a throwaway fan service moment” (in other words, something cheap and commercial).

Many also took offense at the translation of “四两拔千斤” (sì liǎng bá qiān jīn) into “four ounces can move a thousand pounds,” because it came off to them as Disney’s unconvincing attempt to sanitize its orientalism by appropriating Chinese idioms into the imperial units. It comes off as immensely awkward, too, because its context has been taken out: In the 1998 original, Mulan outsmarted everyone by using two golden weights to her advantage in climbing up the pole, which is quite literally an instance of “四两拔千斤”; the live-action, however, took out the element of Mulan’s wit as the exercise was changed into walking up a mountain with two barrels of water, something that could only be accomplished with brute force.

To the great displeasure of fans worldwide, Disney removed the beloved character Mushu from the live action, not because of CGI difficulties, but because of the concern that the 1998 original’s comedic representation of the dragon might have belittled China’s cultural totem. However, not all dragons are created equal in Chinese mythology, and poking fun at lower-tier dragons (the ones of Mushu’s size) happens to be a common theme. Thus, the Chinese audience did not take offense in Mushu’s representation in the animated version. In fact, they were as disappointed as everyone else by the absence of its comic relief. Some pointed out that the 1998 original became a hit in China largely thanks to the legendary comedian Chén Pèisī’s 陈佩斯 superb voice-over for Mushu.

Perhaps remembering the better days of action stars Donnie Yen (甄子丹 Zhēn Zidān) and Jet Li (李阳中 Lǐ Yángzhōng), the Chinese audience was immensely disappointed by Disney’s underwhelming action scenes. The combat scenes were poorly choreographed, the editing was simply catastrophic, and to make everything even worse, the movie copied outdated, clichéd kung fu tropes. One viewer noted that “Mulan lifted many scenes from martial arts classics like Hero, Crouching Tiger, and House of Flying Daggers, and managed to butcher all of them.” Others blamed excessive CGI and excessively unrealistic fight scenes for ruining the mysterious yet solemn atmosphere of the martial arts genre.

As soon as the casting decisions were released, fans doubted why Liú Yìfēi 刘亦菲, who has the reputation of being a mediocre actress in China, deserved to have multiple Oscar-nominated legends as her supporting actors. Many took issue with Liu’s poker-faced acting style, and suggested that Disney should have cast Zhāng Zǐyí 章子怡 as the lead instead.

The movie is also under heavy fire for sidelining its best talents. Fans were not happy seeing their childhood heroes in disappointingly one-dimensional stock characters. The witch played by Gǒng Lì 巩俐, which was hyped by the trailer as Mulan’s anti-heroine, ended up with a baffling character arc and zero psychological depth. Donnie Yen’s general was simply non-consequential, while Jet Li’s emperor, aside from not being a historically faithful character, was only given one shot to demonstrate Li’s martial arts skills. To add salt to the injury, “this wouldn’t be the first time that Hollywood butchered an all-star Asian cast. Remember Jackie Chan’s The Forbidden Kingdom?”

“I want to apologize to Zhāng Yìmóu 张艺谋,” concluded the most brutal comment on Douban. “The Great Wall is f***ing amazing compared to this.”