Rural ecommerce: In China, farmers find new ways to grow

Farm-to-kitchen ecommerce companies are changing the lives of China’s farmers and urban consumers. For a country whose rural sector is dominated by small farms with minimal technology, the use of digital technology is spurring a revolution.

Moving north from Beijing’s center, the glass buildings and clean roadways give way to ramshackle brick structures and dusty roads. Around where one can see mountains rising, there is an organic farm, Everyday People Farms (平人农场 píng rén nóngchǎng), which sells eggplants, peppers, tomatoes, potatoes, and cabbages.

The owner, Zhào Fēi 赵飞, says that profit has increased significantly in the past few years. What has driven the growth? Alongside his physical store, Zhao now runs a WeChat store, a marketplace within China’s ubiquitous app, WeChat, where farmers can become entrepreneurs.

Zhao is not alone. Thousands of Chinese farmers have taken to selling their products online, particularly after COVID-19 struck.

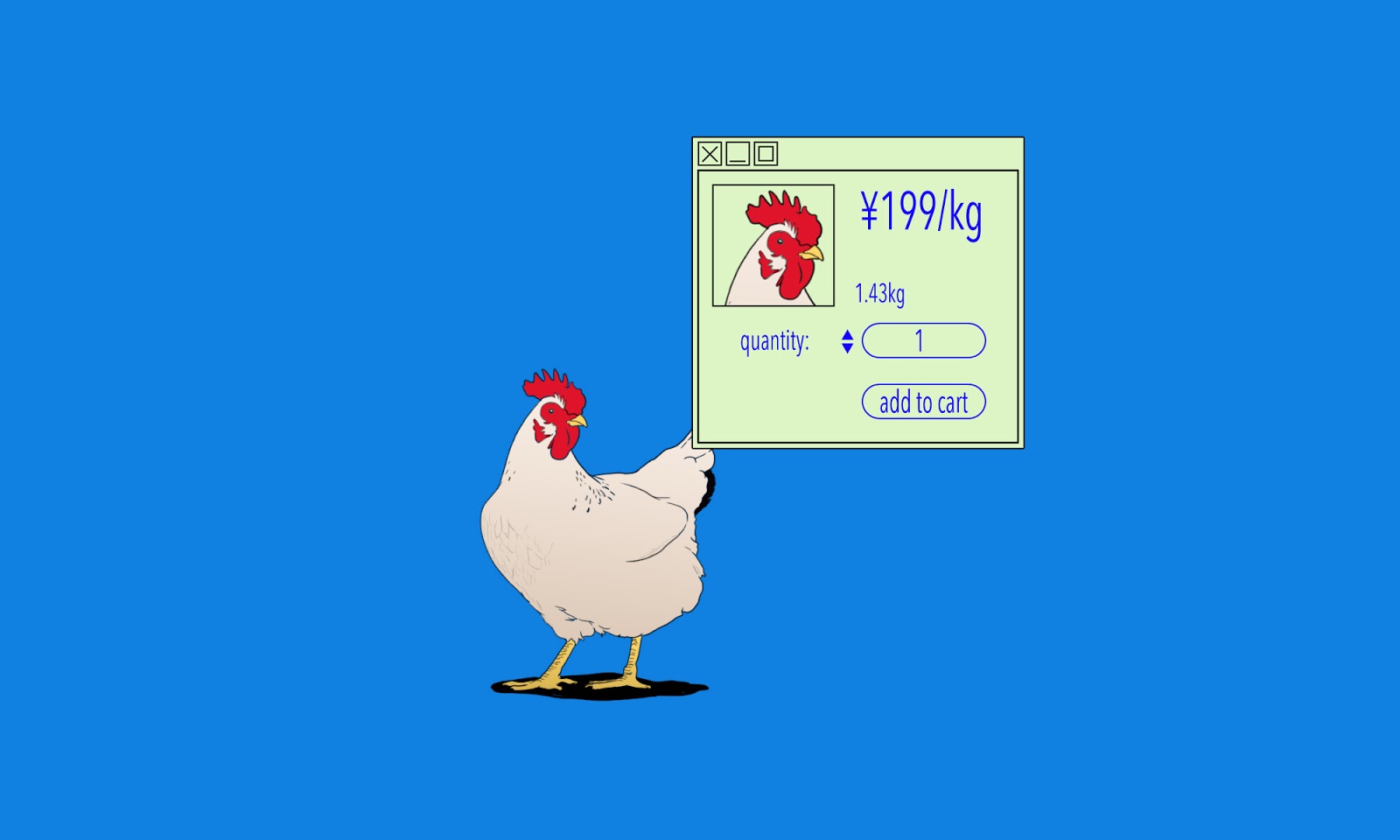

In the first quarter of 2020, Pinduoduo — China’s largest interactive ecommerce platform — saw more than a billion orders in agricultural products on its platform, a 184% increase over the same period in 2019. In 2019, 136.4 trillion RMB ($20.8 billion) of agricultural goods were sold on Pinduoduo. Today, more than half a million accounts are selling agricultural products on the platform, and Pinduoduo is doubling down on its efforts to dominate the farmer-to-consumer market.

“Agriculture is one of the hallmarks of our platform,” said Pinduoduo Vice President for Strategy David Liu.

Pinduoduo is the market leader, but other ecommerce platforms are catching up. Most major ecommerce platforms have set up units to connect farmers to customers. Alibaba plans to sell 400 billion RMB ($61 billion) of agricultural products on its platform by 2022, and WeChat has been reaching out to farmers like Zhao Fei to convince them to set up Wechat Stores.

Institutional barriers holding Chinese farmers back

Ecommerce has long been a force in Chinese retail, but only recently has companies like Pinduoduo, WeChat, and Alibaba begun to impact agriculture, one of the least innovative sectors of China’s economy.

A decade ago, most farmers had limited options for moving produce. They could either sell cheaply at nearby rural markets or sell to major agribusinesses and other middlemen. These middlemen would then sell their products to wealthy consumers in urban areas. A product that goes for as little as 2 to 3 RMB (less than 50 cents) in a local market might fetch 20 RMB (nearly three dollars) in a big city. But going through middlemen meant farmers would lose a significant portion of these gains.

In the mid-’80s, Chinese agriculture became stagnant, even while agriculture underwent a technological revolution in the rest of the world, involving the use of tractors and drones to produce more food with fewer man-hours.

In developed nations, farmers who remain in rural areas have become significantly more productive with the use of machinery. For example, in 1800 in the U.S., 73.7% of the American labor force was in agriculture. Today, only 2.5% of America’s workforce is on the farm, even as the average farm size has swollen to 440 acres.

By contrast, in China, about 35% of its workforce is still in agriculture, and the average farm size is 1.4 acres. Chinese farmers are also generally wary of investing in technology because their farms are too small to make it worthwhile. When a farm does invest in a tractor, it is usually less than 12 horsepower (most riding lawn mowers in the U.S. are between 13 and 30 horsepower). Even today, approximately 28% of the backbreaking work of plowing is done by hand in China. This would be unimaginable in all but the smallest recreational farms in the U.S.

Part of the problem in China is political. The country’s hukou system — essentially an internal passport system — assigns every person born in a rural area a land-use right which guarantees that they will have access to farmland near where they were born (this is a right to use the land, not to own it, as rural land cannot be owned in China). This right is one of the main factors holding back Chinese agriculture. Because the government divides up land equitably and rural hukou holders have a right to it, whether they use it or not, farm plots remain small and relatively inefficient. Since land cannot be owned, farmers cannot borrow against their land, meaning it is hard to build large farms with economies of scale. Farmers who cannot get loans have trouble investing in tractors.

The government has recognized the problem, but it has not yet come up with a solution. In 2013, president Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 made the elimination of poverty, particularly rural poverty, one of the goals of his administration. Recently, Xi highlighted the need for more technology in agriculture, even dropping in on a group live-streaming mushrooms for an ecommerce platform. Chinese farms have tried to innovate, but the fundamental problems holding Chinese agriculture back have changed little. Chinese citizens born in rural areas are still linked to tiny farm plots by their hukou.

The new model

These days, changes spurred by apps are happening so fast that it is hard to keep track. Livestreaming offers an illustrative example. In 2019, Taobao Live struggled to get even 1,000 farmers to livestream their agricultural activities. But COVID-19 turbocharged the platform. By May 2020, Taobao Live had 50,000 rural livestreamers. By the end of this year, the platform estimates that number will quadruple. The turning point came on February 6. In the teeth of the pandemic, the platform allowed all farmers to livestream for free. Farmers responded by selling 15 million kilograms of their products in three days. At one mango farm in Sanya, the mayor livestreamed his farm visit as a way to promote sales. The farm sold 30,000 kilograms of fruit in two minutes.

For urban consumers, watching farmers hoe or pluck fruit allows them to feel a connection with what they are going to eat, and it also assures them that what they are buying is genuine, an issue Chinese consumers have been increasingly concerned with.

This new digital revolution in agriculture echoes the innovation that flourished after Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平 opened up China’s economy in the late 1970s. Peasants were among the first to abandon Maoist collectives, transforming themselves into private entrepreneurs. Between 1978 and 1984, rural household income increased twice as fast in rural areas as in urban ones.

These days, in cutting out the middlemen, internet companies are making the farm-to-table sector of Chinese agriculture even more efficient than in America.

Silicon Valley has attempted to connect farmers to consumers. Companies like CrowdCow allow for “Steakholders” to purchase shares of an animal and get the cut shipped to them. CropSwap does something similar for local produce. Many other farms market their products directly to customers via Facebook or Instagram. But these efforts are piddling compared to what is happening on Chinese platforms.

“China is leapfrogging the rest of the world in integrating ecommerce and agriculture,” says Dr. Carmen Leong, a senior lecturer at the University of New South Wales Business School.

China’s social media giants like Alibaba and WeChat have already shown that they can supersede Silicon Valley. In the area of agriculture, China’s social media giants may do it again.