China’s 10 richest people in 2020

The Hurun China Rich List annually recognizes China’s wealthiest. This year’s Top 10 includes familiar faces, mostly self-made billionaires who came of age when the country was poor. Who are they?

Against all odds, 2020 has been a good year for the fattest of China’s fat cats. The Hurun China Rich List (ranked alongside Forbes as a definitive record of Chinese personal wealth) has recorded a larger wealth boost this year than the past five combined — $1.5 trillion — thanks to numerous IPO listings and the side effects of pandemic life. “The world has never seen this much wealth created in just one year,” says Rupert Hoogewerf, the list’s chief researcher.

The country now has 878 U.S. dollar billionaires — it had zero back in 2003. A look at the lives of those who make up the Top 10 is to sample a cross-section of the industries and personalities driving China’s economic boom. These 10 have some exceptional qualities — assertive, determined, and courageous — willing to sacrifice stable jobs (all-important in Chinese society) and take their chances in waters less charted.

Some of the 10 are the product of the dotcom boom, that began when China logged onto the internet in 1994. But most started in the absolute poverty of the Mao years, clawing their way up from nothing.

It’s unlikely there are many U.S. billionaires from this generation who have quite the same “rags to riches” story as those who studied by kerosene lamps, or cleared sewage drains to get on the job ladder. Who are these people? Let’s take a look at the following 10, who have a combined net worth exceeding the GDPs of more than 160 world nations.

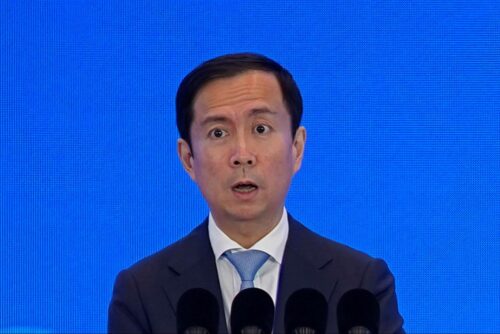

Jack Ma (马云 Mǎ Yún) — $58.8 billion

China’s Richest Man and best-known billionaire is a five-foot, big-headed, scrawny tech rock star, often appearing in traditional Chinese suits or displaying his tai chi prowess. He’s been top of the Hurun List for three years in a row, his $58.8 billion the hard-won earnings of his internet goliaths Alibaba, Taobao, and AliPay.

Ma was born the middle child of poor musicians in Hangzhou in 1964. He didn’t excel at school, once getting only 1 out of 120 in a university entrance exam. He tried three times and passed on the third (albeit to the worst university in Hangzhou), having learned English from riding on his bike at 5 a.m. every morning to the local international hotel, showing tourists the city in return for English lessons.

It was this sort of confidence, flexibility, and perseverance that made it possible for him to plow on, despite being consistently turned down from vacancies — even at KFC. It led him to keep going despite the failure of two previous search engine start-ups. It was how he persuaded Goldman Sachs to invest in Alibaba when it launched in 1999 (the new search engine buying up the stock of every company that listed with them — storing it all in a garage — to boost people’s confidence). Keeping employees confident and energized was of such importance that they were made to do handstands during breaks to keep the blood flowing.

For him, education isn’t everything. “I’m running one of the biggest ecommerce companies in China, maybe in the world, but I know nothing about computers,” he confessed in 2014. What he knows, he knows through life experience — he spent three years trying to persuade Chinese companies to commission him to design websites for them, despite the internet being a little-used fad at the time. “I was treated as a con man,” he later admitted.

Aside from the company, Ma indulges in games of Go and painting (one of his works selling for $5.4 million in 2015 in Hong Kong). Ever the showman, in 2009 he performed in a flamboyant punk-rocker outfit for 20,000 of his employees.

How many corporate leaders would have had the confidence to do that?

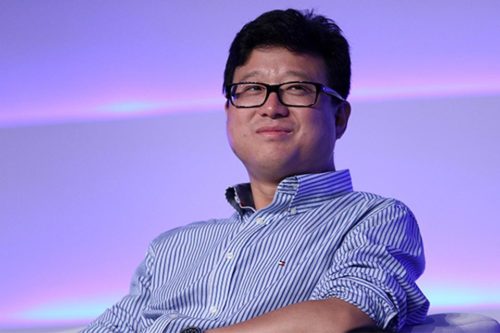

Mǎ Huàténg 马化腾 — $57.4 billion

The rivalry between Tencent and Alibaba, China’s two internet giants, is well documented. Both vie for users of their payment, gaming, and ecommerce apps.

But the two Mas couldn’t be less alike. Where Jack Ma is outgoing, Tencent CEO Ma Huateng (Pony Ma) is low-key. Very little is known about his private life, and he prefers to keep interviews strictly on his work and his beliefs.

The man behind WeChat and QQ was born in Guangdong in 1971, either to a poor or “relatively well-off” family. They moved around the country in search of his father’s next job, settling as a port manager in Shenzhen. From there, Ma went on to study computer science at Shenzhen University, using the city as a power base for his future business.

Ma takes a keen interest in astronomy thanks to his parents giving him books on the subject when he was a child, his company now investing in start-up ideas for a future space-age.

The owner of WeChat also served as a deputy to the 12th Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC). He has stated, “Lots of people think they can speak out and that they can be irresponsible. I think that’s wrong…We are a great supporter of the government in terms of information security.”

Zhōng Shǎnshǎn 钟睒睒 — $53.7 billion

Due to the dubious quality of Chinese tap water, it’s no surprise the country’s market for bottled water is thriving. The red-capped bottles of Nongfu Spring are a staple of corner shops, offices, and restaurants, but the company has since branched out into coffee, juice, and sports drinks, all overseen by Zhong Shanshan.

The beverage tycoon was born in Hangzhou in 1954, dropping out of school at 12 during the Cultural Revolution when his intellectual parents were persecuted. He scrabbled around in torn cloth shoes on building sites until 1977, when he enrolled at Zhejiang Radio and TV University.

He then went through a string of jobs — journalist, mushroom-seller, and peddler of erectile dysfunction pills — before founding Nongfu in 1996.

Known as the “lone wolf” for his lack of interaction with his billionaire peers and reclusive lifestyle, Zhong has had his fair share of hard knocks — like accusations from the Beijing Times in 2013 that his water was inferior to tap water. But this year he’s shot up to the top three thanks to the IPO of Nongfu. It also helps to own a vaccination company (Beijing Wantai Biological) during a pandemic.

Wáng Wèi 王卫 — $35.3 billion

Although SF Express is one of the largest delivery companies in China today, it started with 6 smugglers in a minivan. It’s the empire of Wang Wei, another reclusive Shenzhen billionaire.

Born in Shanghai in 1970 to a Russian language translator and a university professor, the family moved to Hong Kong when Wang was 7 — but Chinese degrees were worthless over the border, meaning the family was immediately impoverished. Wang didn’t go to university, instead getting a job as a laborer with his uncle.

Later on he set up a printing and dyeing factory in Foshan. Wang was frustrated at delays to get samples into Hong Kong, so he started smuggling packages across the border. Friends would ask him to take their packages too. Smelling demand, in 1993 he set up Shunfeng Express, carting goods across the border illegally.

Not even his own company’s internal magazine has managed to get an interview from him.

He’s known for being very dedicated to boosting his brand’s quality (an obsession, according to the South China Morning Post) and looking after his workers — he reportedly once told colleagues, “I know the taste of being poor, of being discriminated against by people for being poor.” When his company registered its IPO in 2017, he arranged for a driver slapped by a sports car driver after a collision to ring the opening bell.

Pandemics have been useful for his business. During the SARS epidemic of 2003, airline prices plummeted, allowing him to negotiate with a desperate Yangtze River Express (now Suparna Airlines) so that his courier company would be the first in China to charter flights. This similarly isolated year has seen his wealth double, putting him in the Top 10.

Xǔ Jiāyìn 许家印 — $34.6 billion

Xu Jiayin is chairman of Guangzhou-based Evergrande Group, one of the largest property developers in the country.

Born in rural Henan 1958, his mother died when he was only 8 months old, so he was brought up by his grandmother and father (a retired soldier). After high school, his jobs included security guard (of the village livestock), shifting lime between towns for tiny profits, and shoveling dung.

When the national college entrance exam was reinstated starting in 1977, Xu tried twice to pass the exams. According to an article he wrote about his childhood, the training school was so full at one time that he had to live in a hut, with a -15 C wind blowing through a broken window. Training in metal work at the Wuhan Institute of Iron and Steel, he was often the one to volunteer to keep the sewage flow clear in the college latrines. He subsisted on 10 yuan per month ($1.40), taking his classes while eating little more than sweet potato and moldy buns. He claims his favorite food is still cheap dry noodles.

He clawed his way up from working in metal production to becoming a property tycoon in Guangzhou, the proud owner of a football club and a volleyball team (coached by none other than Láng Píng 郎平).

But he doesn’t seem to have forgotten his roots. In 1999, he donated 1 million yuan ($152,000) to his old village, asking them to build a school.

Hé Xiǎngjiàn 何享健 — $33.1 billion

At one time, a fifth of China’s home appliances were being made in the town of Beijiao, Guangdong, thanks to the ambition of He Xiangjian, chief shareholder of Midea Group.

Born in 1942, He never attended university, working as a farmer after leaving high school. In 1968 he started a ramshackle plastics factory in the town — it was illegal at the time due to being outside the planned system. Kerosene lamps were used to melt and mold the plastic, workers unable to see through its thick smoke.

The factory was finally able to go public in the 1980s. Appliances brought back into China from Hong Kong and Macao sparked He’s mind, and he decided to upgrade the factory, first to fans, then air-conditioning. The demand for consumer goods exploded over the decade.

Today the company is branching out into robotics, keen to pioneer the future. He Xianjian is another recluse, but was in the news due to a prominent break-in to his home in Foshan, men armed with explosives aiming to kidnap him. He’s also the first boss of a 100 billion yuan company to hand chairmanship over to someone other than his son, choosing a protégé named Fāng Hóngbō 方洪波.

Yáng Huìyán 杨惠妍 — $33.1 billion

China’s richest woman is also the only billionaire in Hurun’s Top 10 who isn’t self-made. Born in Guangdong in 1981, Yang is the second daughter of Yáng Guóqiáng 杨国强, who went from farming to founding Country Garden, one of China’s largest property firms.

Yang Sr. groomed his daughter to become his successor, taking her to board meetings when she was just a girl and sending her to study in America. Upon returning home she immediately entered the company as purchasing manager. Within a year she was promoted to executive director.

Aged 24, she married a Tsinghua graduate, son of a senior government official in the northeast. In 2007, Yang Sr. transferred all of his company shares to her before the company’s IPO.

As an employer she’s been called “the girl next door,” who smiles a lot but rarely speaks. Her adept steering of the company through the turmoil of the 2008 global financial crisis has proved her a competent executive. But according to one Chinese article, her real ambition had been to be a teacher. Perhaps this is why she chairs Bright Scholar Education Holdings, the biggest operator of bilingual K-12 schools in China.

She’s also been caught up in a citizenship scandal, involving the Cyprian government issuing passports to 500 wealthy Chinese. She appears to now be “Cypriot-Chinese,” even though China doesn’t accept dual nationality.

Dīng Lěi 丁磊 —$32.4 billion

NetEase is nowhere near as big a digital fish as Tencent, but it was one of the biggest Chinese internet companies during the early 2000s, its selection of games (later including the best-selling Fantasy Westward Journey), making its founder Ding Lei the richest man in the country in 2003. Ding is still doing all right for himself, recently buying up an L.A. mansion once owned by Elon Musk.

Born in Zhejiang in 1971, Ding was making and assembling radios by the time he was 16, determined to become an engineer. By the time he got to the Chengdu Institute of Radio Engineering, he was pouring through IT manuals and learning how to code — not a great student, but always willing to put forward his ideas.

He was convinced the internet would become a huge part of Chinese life, quitting a respectable job in China Telecom (against the wishes of his family) in 1995. NetEase became popular for its free bilingual email service but suffered setbacks in 2001 due to false revenue reports. But his fortune was secured during the chaos of SARS, when millions turned to his mobile games and messaging services.

He’s a man intent on creating his own luck. “People who want to be strong always create opportunities,” he told a class from his alma mater. “Smart guys seize opportunities and never let them slip between their fingers. And those who think themselves weak always wait for opportunities.”

Colin Huáng Zhēng 黄峥 — $32.4 billion

Pinduoduo has a polarized reputation in China. Some see it as a platform peddling shoddy goods, doing its utmost to turn consumers into addicts with its merger of games and commerce. Small businesses in lower-tier cities see the platform as a golden opportunity to buy goods at bargain prices.

Either way, it’s a remarkable success story in the world of Chinese ecommerce, somehow thriving in an industry dominated by Alibaba. It’s the brainchild of Huang Zheng, a 40-year old tech whizz born to factory workers on the outskirts of Jack Ma’s turf in Hangzhou.

Identified as a bright child, Huang studied at the prestigious Zhejiang University before going to the University of Wisconsin in 2003 to pursue a degree in Computer Science — he’d already been noticed as a programmer, contacted by Ding Lei (already famous) for help on technical problems.

Bizarrely, he turned down a job offer from Microsoft (despite out-earning his parents even as an intern), deciding instead that the fledgling Google looked more promising. He returned to China in 2006 with the vanguard of Google employees — trying to make themselves China’s primary search engine.

Huang disliked the company’s intense micromanagement and left a year later, starting a string of start-ups before hitting on the idea of an app offering heavily discounted products (the price is lowered if you get friends to chip in). His wealth skyrocketed by 63% this year, thanks to a locked-down population focusing on online games and shopping.

Qín Yīnglín 秦英林 and Qián Yīng 钱瑛 — $29.4 billion

Bringing up the rear are two pig farmers from Henan, who together sit on the board and are majority shareholders of Muyuan Foodstuff Company, one of the largest pig-breeding companies in the world’s largest national pork market. Agricultural jobs aren’t considered very prestigious in China, but thanks to the market disruption of swine flu and COVID, for the past two years the couple has shot up the rich list.

Qin Yinglin spent his childhood in poverty from the late ’60s to early ’70s, his parents encouraging him to go to university during Reform and Opening Up in the 1980s. He and Qian met in their “iron rice bowl” jobs (the term for lifelong state employment, highly coveted at the time) in the animal husbandry unit of Nanyang City. Strangely, they decided to move back to the countryside and launch a breeding farm.

They put their knowledge to good use. Starting with just 22 piglets in 1992, their sties were home to 10 million 20 years later.

Chinese Lives is a weekly series.