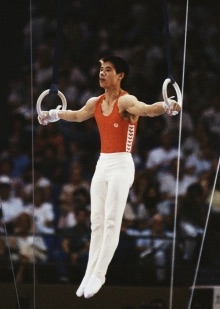

It was quite the heist. Li-Ning Company Limited, at the time China’s largest homegrown sportswear company, had lost the bid to Adidas to exclusively hold the sportswear advertising rights to the 2008 Olympics. But somehow the company’s chairman and namesake, Lǐ Níng 李宁, the “Prince of Gymnastics” himself, was hoisted up to light the gigantic torch on the roof of the Beijing National Stadium, flashily dressed in his own branded trainers. Revenue rocketed by 54% while Adidas whinged about the stunt violating its exclusive rights.

Few in China cared. Their Olympic team had been wearing Li-Ning for decades, and the man was of such stature at home and abroad that it only seemed right he be showcased at the opening ceremony. “Li Ning remains one of the sport’s most admired competitors,” wrote the International Gymnastics Hall of Fame in 2000. “His originality, quickness, strength and explosive power is legendary.”

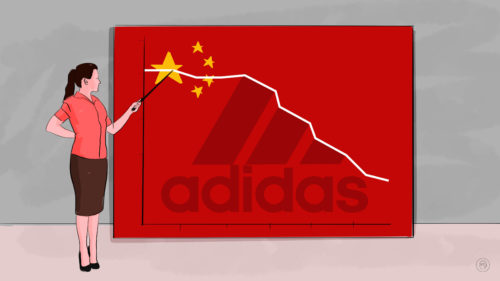

The Li-Ning Company has always been tied to national pride — named after the man who won 106 medals for China over his 19-year career — and has capitalized on its homegrown credentials in the face of foreign competition. Its most recent news splash was during the Xinjiang cotton boycott, when Nike and Adidas were being shunned in China alongside H&M for their stance on forced labor in Xinjiang. The Weibo hashtag “Li Ning puts Xinjiang cotton on his labels” was viewed hundreds of millions of times, ensuring the company’s stock price rose 10% in just two days.

But shares in Li-Ning had already been on the up for a while, prices tripling since last year. Although the company is still dwarfed by giants Anta (a domestic competitor) and Nike, the company is “a bellwether for China sports fashion and even the wider apparels industry,” according to Rupert Hoogewerf of the Hurun Report, always “at the cutting edge…of the industry.” His new sportswear collections are a staple of “Guochao,” a new movement in fashion and design, Chinese brands updating traditional Chinese aesthetics for the 21st century (aiming to make Chinese consumers feel pride for things “made in China”).

Who is Li Ning?

A legendary gymnast-turned-billionaire, with a current estimated worth of $20 billion, according to the Hurun Report (which does an annual China Rich List). Li rarely talks about his early life in interviews, preferring to focus on the present and future. But in a 1999 interview with New Sports Magazine, he gave credit to a few people. One of these was Zhāng Jiàn 张健, the coach who trained him into a champion.

What the Chinese knew of gymnastics, they knew from the Soviets. A delegation had been sent out there in the 1950s, but the Cultural Revolution put a halt to most Western sports. A revival started in the late 1970s in preparation for international tournaments, where China was expected to hold its own. The country was determined to break the “big duck egg” — a reference to how many total medals China had ever won at the Olympics: zero.

Li (like hundreds of other young children across China) was plucked out of school in Guangxi at age 8, chosen for his “short stature, good speed and jumping,” according to Zhang. By 1973, just two years later, he was already making waves, championing floor exercises at the National Junior Gymnastics Competition — this was the time when the “little monkey” first attracted Zhang’s attention, becoming Li’s guardian angel. When Zhang asked the national team why Li hadn’t made it, he was told it was because Li was “too naughty.” Zhang made sure he got onto that team in 1980.

Training for Chinese Olympic teams was grueling, candidates placed in institutions that combined boarding school and boot camp, with bunk beds, early-morning roll-calls, and marching drills. But it clearly molded Li, both physically and mentally. In a 1999 interview with New Sports magazine, Li said Zhang “turned me into a man who knows how to be responsible to himself, to gymnastics, to the team, and to society.”

He started doing well. In 1982, he earned six out of the seven medals up for grabs at the World Cup Gymnastic Competition, an astonishing achievement. But his crowning glory would come two years later at the Los Angeles Summer Olympics.

There, his performances in floor exercise, pommel horse, and the rings became legendary, both in China and the international sporting community. He was the most-decorated athlete of those games, winning six medals (three gold, two silver, one bronze), and had gymnastics moves on the rings and pommel horse named after him. He was invited to become a member of the IOC Athletes’ Commission in 1987, the only Asian to get an invite. Alongside Láng Píng 郎平 and the China women’s volleyball team, 1984 was the year when, according to Dr. Susan Brownell, an expert on Chinese sports at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, “China’s dream of regaining what it regarded as its rightful place as a world superpower began to seem like more than a fantasy.”

But having risen so high, Li began making the most embarrassing of mistakes at the 1988 Seoul Olympics: Falling after missing the rings mid-swivel, and landing flat on his ass when completing a pommel horse routine. “He made a smile before the camera. But when he returned to the restrooms he burst into tears,” former CCTV commentator Song Shixiong told ShanghaiEye. Such pratfalls led to a big fat duck egg of his own.

A turn toward business

Li swapped jobs while waiting for the plane home. At the Kimpo International Airport he supposedly bumped into Lǐ Jīngwěi 李经纬, another man he credited for his success. Li was a wily businessman who owned Jianlibao Group, at the time China’s most famous sports drinks brand. Li Jingwei knew that Li Ning had a recognizable brand in himself, which, although damaged in 1988, still sparkled.

Li Ning retired from sport that year (aged 26), but would never be forgotten — honored as “one of the world’s most excellent athletes” by the World Sports Correspondent Association in 1999. Unlike other athletes who usually became coaches or bureaucrats, Li went into business. In 1990 he was offered a job as general manager for the new “Li-Ning” brand under the Jianlibao umbrella, spinning off into Li-Ning Company Limited in 1994, selling professional sports gear, which several commentators noted as having a more-than-passing resemblance to Nike’s.

It’s unclear how Li Ning’s company managed to break onto the national stage while its municipal-government-owned parent company crashed into oblivion when it tried to do the same in the early 2000s (later, Li Jingwei was cuffed by local authorities for corruption). Perhaps, as Brownell suspects in her essay “Why 1984 Medalist Li Ning Lit the Flame at the Beijing 2008 Olympics,” there was political guanxi involved. “The leadership in Beijing was interested in seeing the creation of ‘national brands’ that could fly the flag of Chinese national pride, and a company owned by a small city in south China was unlikely to fulfil this function.”

What made the brand so special was Li Ning’s personal reputation, his 1984 successes now permanently linked to national pride and prestige. It was how he convinced the State Sports Commission in 1990 to award his company with brand rights for the 11th Asian Games in Beijing, despite bidding less than foreign brands. The commission was won over by the pain he claimed to feel by having to wear foreign brands as a Chinese Olympic champion.

The brand became fashionable, boosted by the publicity of the Asian Games and a strong rural consumer base. Turnover rocketed during the mid-1990s, and it became standard for Chinese athletes to appear at the Olympics in Li-Ning clothes. By 2004, Li-Ning was the largest Chinese sporting goods company on the Hong Kong stock exchange. Li was keen to put his days as an athlete behind him. “I am an entrepreneur with more than 10 years of business history,” he puffed to the press around this time. “Please stop thinking of me as a star idol.”

Instead of merely consolidating his hold on the domestic market, Li aimed for the international market, setting up a chain of U.S. stores. Alas, his company had little knowledge of American consumer tastes. A 2010 Time article noted how “the products in the Portland store do not shy away from Li-Ning’s origins, highlighting apparel for popular sports in China like badminton, table tennis and kung fu.”

The company began to fall on hard times in the early 2010s once Li left. Losses piled up. Suddenly, Li-Ning began to seem old-fashioned, failing to win over the younger generation of consumers more attracted to branding of “excitement, lifestyle, and coolness,” rather than “patriotism and national pride,” according to market analysts. Attempts to win over young people through rebranding were botched, also alienating the older generation. Three CEOs came and went before Li returned to the chair of the Board of Executives.

Under his renewed tenure, the company has branched into sports fashion, becoming a trendsetter sitting at the intersection between youth culture, patriotism, and traditional Chinese design. The new “中国李宁” (zhōngguó lǐníng, China Li-Ning) collection — in the characteristic red and yellow “egg and tomato” colors of the Chinese flag — wowed China and the world when unveiled on the runways of New York and Paris Fashion Weeks in 2018. Channeling hip-hop culture, the brand became trendy, one “young people are proud to wear,” according to Daxue Consulting. It was at once both identifiably local and triumphantly global: the first Chinese sports brand to land on fashion runways in the West, while fashion shoots in traditional Beijing hutongs injected a quintessentially Chinese identity.

Even the Party is getting behind Li-Ning. A long queue formed outside the People’s Daily media department in 2019 (that is, according to their own coverage) when the two brands paired up, a new collection appearing with “People’s Daily” written across the sleeve in English. It’s hard to find a precedent for the dusty People’s Daily being so youthful and vogue.

But perhaps the company’s best move was the signing of Xiāo Zhàn 肖战 (Sean Xiao) — still by far and away the hottest youth idol right now — as a brand ambassador at the start of April, giving them access and exposure to Xiao’s gigantic base of young fans. The brand can hardly be accused of being old-fashioned now.

Although it’s all-change at Li Ning’s company, the base factors that made it appealing to consumers have never wavered. When it comes to pushing foreign brands out of the way for his own ascendant moment on a tide of national fervor, the thousands of social media comments posted during China’s recent H&M boycott would have been similar to the public’s reaction to his stunt in 2008: “Support Li-Ning!!”

Chinese Lives is a recurring series.