Hong Kong celebrates a record Olympic run amid political controversy

Hong Kong, which competes in the Olympics as a separate team from China but plays the P.R.C. anthem at award ceremonies, has won more medals in Tokyo than at any previous Games. While much of the attention was on the impeccable display of talent, the city’s moments of triumph were also marked by political controversy.

Yesterday, the Hong Kong women’s table tennis team bagged the city’s first-ever bronze medal in the event at the Tokyo Olympics. Doo Hoi-kem (杜凱琹 Dù Kǎiqín), 24, Lee Ho-ching (李皓晴 Lǐ Hàoqíng), 28, and Minnie Soo Wai-yam (蘇慧音 Sū Huìyīn), 23, defeated Germany with a scoreline of 3-1. Shortly after, Grace Lau (劉慕裳 Liú Mùshang), 29, won a bronze medal in the Games’ first women’s solo karate competition.

Last Friday, Siobhan Haughey, 23, became the first multi-medalist from Hong Kong after winning a silver in the 100m women’s freestyle and another silver in the 200m women’s freestyle on Wednesday.

This came after Edgar Cheung Ka-Long (張家朗 Zhāng Jiālǎng), 24, made history by bagging Hong Kong’s first gold medal in men’s individual foil last Monday, after beating Italy’s Daniele Garozzo — the first gold since the 1997 handover of the city to the Chinese rule.

While much of the attention was on the impeccable display of talent, the city’s moments of triumph were also marked by political controversy.

Even though the city competes as a separate team under the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region flag with different jerseys from the People’s Republic of China team, it is the Chinese national anthem that is played for it at medal award ceremonies.

Man arrested after police investigate booing of Chinese national anthem

Thousands of people gathered in malls across the city to cheer for Chueng and Haughey. However, the city found itself divided as the flag-raising ceremony was met with a chant from the crowd of “We are Hong Kong,” and booing at the Chinese national anthem from some.

Videos circulated online — with some racking up more than 200,000 views — showed the anthem replaced with the popular protest song “Glory to Hong Kong,” the lyrics of which are now considered secessionist by the government and hence possibly illegal under the sweeping new National Security Law. The law was promulgated unilaterally on July 1, 2020, by Beijing and criminalizes acts of subversion, secession, terrorism, and collusion, which are all punishable by a life sentence.

In June 2020, mere weeks before the imposition of the National Security Law, Hong Kong passed a National Anthem Law that criminalizes insults to the National Anthem of China, and carries a maximum penalty of three years in jail.

This year on Friday, July 30, a few days after the booing incident, the police said that they had launched an active investigation. That evening, the police confirmed that a 40-year-old journalist had been arrested for “inciting others on site to boo and chant slogans.” Meanwhile, the same day, the first trial under the National Security Law ended with the accused getting a nine-year jail sentence for terrorism and secession.

Politicizing outfits

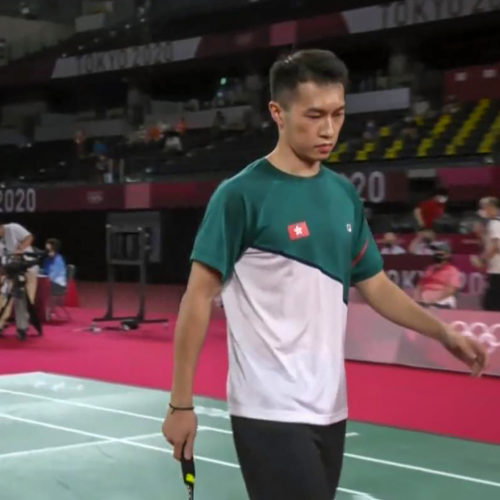

On July 24, Nicholas Muk (穆家駿 Mù Jiājùn), a member of the pro-Beijing party Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB), blasted the city’s badminton player Angus Ng Ka-Long (伍家朗 Wǔ Jiālǎng), 27, for his attire at the Olympics as his T-shirt was missing the bauhinia emblem and instead just bore the team name “Hong Kong, China.”

Unlike Cheung or Haughey — both of whom had sponsors during the event — Ng’s sponsor had backed out at the last moment, forcing him to arrange for his own clothing. Globally ranked number 9, Ng said on social media that under the regulations, he’s not allowed to print the regional flag of the city without government authorization.

If the lack of sponsorship wasn’t enough, even the black color of his attire attracted the ire of many pro-Beijing figures, including Muk, for wearing the color that was worn widely by the pro-democracy protesters in 2019 in opposition to the government. This, combined with the lack of the emblem, attracted dozens of hateful comments, some of whom even started to blame Cheung, confusing him with Ng, since they both share “Ka-Long’’ in their names.

Senior counsel and adviser to the chief executive Ronny Tong (湯家驊 Tāng Jiāhuá) commented that Hongkongers “are afraid of the dark after encountering ghosts [referring to the 2019 protesters], so you’d better avoid wearing black, otherwise, some may have a heart attack while watching television.”

His jersey for the first group stage match was, however, perfectly aligned with the International Olympic Committee’s guidelines, which require the athletes to display their name and the delegation they represent, “Hong Kong, China.”

The Hong Kong Badminton Association (HKBA) took the blame in a statement and vowed to improve the “communication between the badminton teams” and arranged for a jersey via the event sponsor FILA.

None of the athletes, including Ng, had expressed any political views. In fact, they were required to sign a declaration that barred them from being political at the Games. Yet they found themselves in the crossfire of the intense divide that plagues the city.

The head of Hong Kong’s delegation to Tokyo, Pui Kwan-kay (貝鈞奇 Bèi Jūnqí), said that he hoped “people would stop politicizing the incident” and that the delegation will focus on the Games “hoping outside forces won’t affect the athletes.” He added that no athlete would omit the emblem, as they see representing Hong Kong as an honor.

After much backlash from the public as well as from his own party, last Wednesday, Muk finally apologized to Ng days later about the incident — an apology that many pointed out was only for the tone Muk used and not the content.

By that time, the blow had already been dealt and Ng lost his race in the Games to the Guatemalan with the world rank of 56, Kevin Cordon. He said after the match that his mental state had been affected and that he just wanted the jersey saga to pass.

He hoped that “people can focus more on athletes’ performance, rather than things off the court.”

The tally for Hong Kong at the Tokyo Olympics 2020 currently stands at five, which is already its best run, with this year’s total surpassing all its previous medals combined. And for a city so heavily divided, the Olympics seemed to offer what we all have lost in Hong Kong — a sense of unity, which, however, was short-lived.