Beyond the Mask

The story of the misunderstood facekini

This article was originally published on Neocha and is republished with permission.

Stepping off the elevator, a handwritten sign with a crudely drawn arrow reads, “Swimsuits, diving suits: pickup area.” A long dark corridor leads us to unit 501, an office space that feels more like a stockroom; it’s cluttered with all sorts of swimwear, boxes, and clothes racks. The Qingdao sea is barely visible through the large window, a slit of water squeezed between buildings on the gray, wintry morning.

We’re greeted by Zhang Shifan and Liu Keliang, a neighborly couple in their seventies and the owners of swimwear brand Sturgeon Dragon. Zhang wears a nondescript sweater and has her hair tied back in a bun. Liu wears a dark brown leather jacket and Nike shoes. He’s the one who began explaining the story of their business when we were barely past the door.

Seventeen years ago, his wife Zhang invented the facekini, a Lycra swimming mask that starts at the collarbone and covers the entire head, available in several colors and patterns. Because of its unconventional design, Zhang’s invention gained international notoriety, being featured in publications like The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Vogue. Over the years, the facekini became a global curiosity, a fashion statement, and the source of much controversy.

Despite the common belief that it’s a sun-protective mask, the facekini originated from another practical need at the beaches of Qingdao: protection from jellyfish stings. Many species of jellyfish bloom on the Yellow Sea coast, where Qingdao is located, sometimes weighing more than 100 kilograms and ranging up to two meters. As they commonly reach shallow shore waters, they pose a threat to beachgoers.

When Zhang was six years old, she witnessed how dangerous these animals can be. Her family lived on a military base and once hosted an army nurse. One day, while training out at sea, the nurse was severely stung by a jellyfish. She was wearing a swimsuit with long sleeves, so her arms and most of her body were protected, but her face and hands swelled up with large red patches.

To this day, Zhang clearly remembers the night that followed the incident. “We took her home for my grandmother to treat her, but she was suffering through the night!” With the cries of the nurse echoing through the night, Zhang couldn’t sleep. “I just remember thinking if only her clothes covered a bit more, she wouldn’t be suffering that much.”

Going to the beach was not a big part of Chinese culture until the Europeans arrived. For a brief period, Qingdao fell in the hands of German colonizers as the capital of the Kiautschou Bay concession, and in the early 1900s, they introduced activities such as diving and promenading to the city. Still, the local population rarely took part in them.

Living by the sea, Zhang saw the evolution of beach culture in China. In her childhood, going to the beach revolved around activities such as picnicking or fishing. Swimming was only an afterthought. Beachwear was also uninspiring and conservative at the time. “It was horrible! It was all made of cotton, and the stretching was not good,” she recalls. “After a little while, clothes would look baggy and loose. Colors faded fast, and they would form lint balls.”

Things changed little until the late 1980s when Lycra fabric finally arrived in Qingdao. “Lycra is far more structural. It shapes the body nicely and pushes the breasts up, putting them in the right place,” Zhang says, gesturing with her hands with a spark in the eye. With the introduction of the material, vivid colors and patterns brightened the beaches of Qingdao, making beach culture more commercial and even sensual, opening up the expanding niche of leisurewear.

Around the year 2000, Liu owned a manufacturing company supplying swimwear to brands across the world. He was also an inventor, designing machines for high-resistance training, such as underwater treadmills and bicycles. Once, he was even commissioned to design an underwater bicycle for athletes training for the Tour de France.

One of Liu’s American buyers, a 73-year-old woman who was the president of a swimwear brand, once visited his manufacturing facilities in China. Zhang, fifty at the time and retired from her accounting job, was fascinated by her, and by the fact that she was running her own successful business on the other side of the world. She suddenly realized that she could do the same. So, with deadstock fabric from Liu’s factory and studying his product catalogs, Zhang began designing her own line of swimwear. She quickly opened a brick-and-mortar shop by the beachfront to cater to the local market. Still, sales were slow at first, and she realized she needed something different to attract new customers.

Zhang noticed that many people who came into her shop shared a common fear. “They were afraid of swimming because of jellyfish! Many of them would even wear long Johns to go into the water. Sometimes they would wear their pajamas. It all looked awful, and uncomfortable to swim.”

Zhang’s first hit was a Lycra wetsuit covering most of the body, exposing only the feet, hands, and head. She and Liu had the idea of printing her telephone number on the back of the wetsuit. The design was dull, unflattering by most people’s standards, but it was surprisingly effective marketing for their business. Zhang’s first customers were like walking—and swimming—advertisements. Her phone never stopped ringing. Her first batch flew off the shelves, and they put her swimwear shop on the map.

Business was going well, and Zhang was happy. But one day, a woman in her forties made a remarkable observation. “You’re doing something right. But only halfway,” she said. Then the woman pointed at her own head. “Our heads are still exposed!” Zhang’s mind went back to the incident with the nurse, and it all clicked.

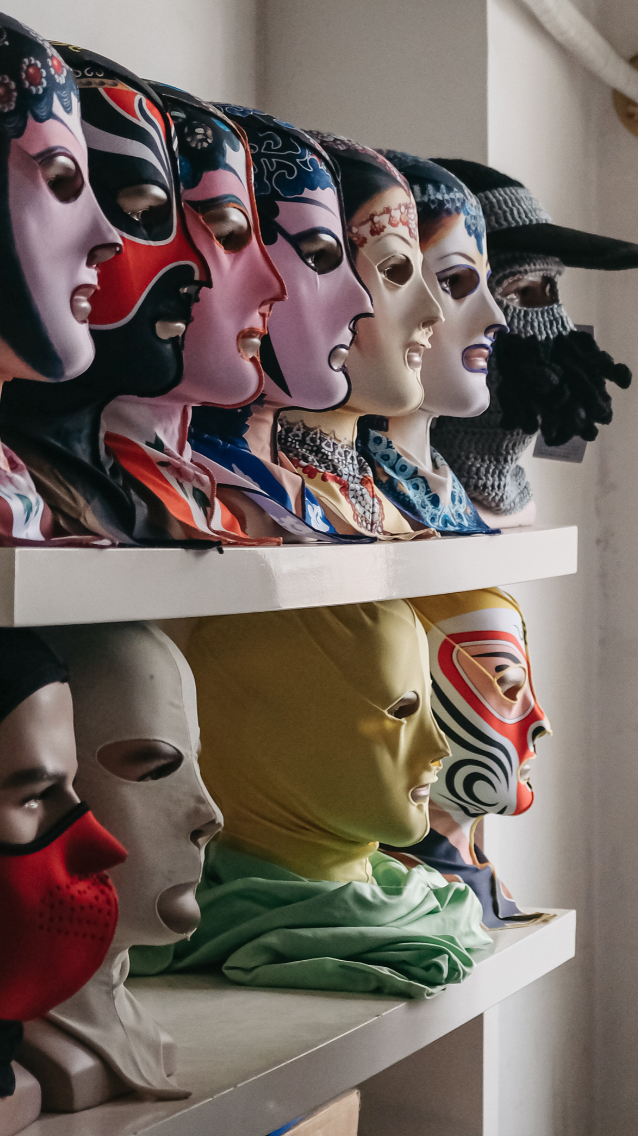

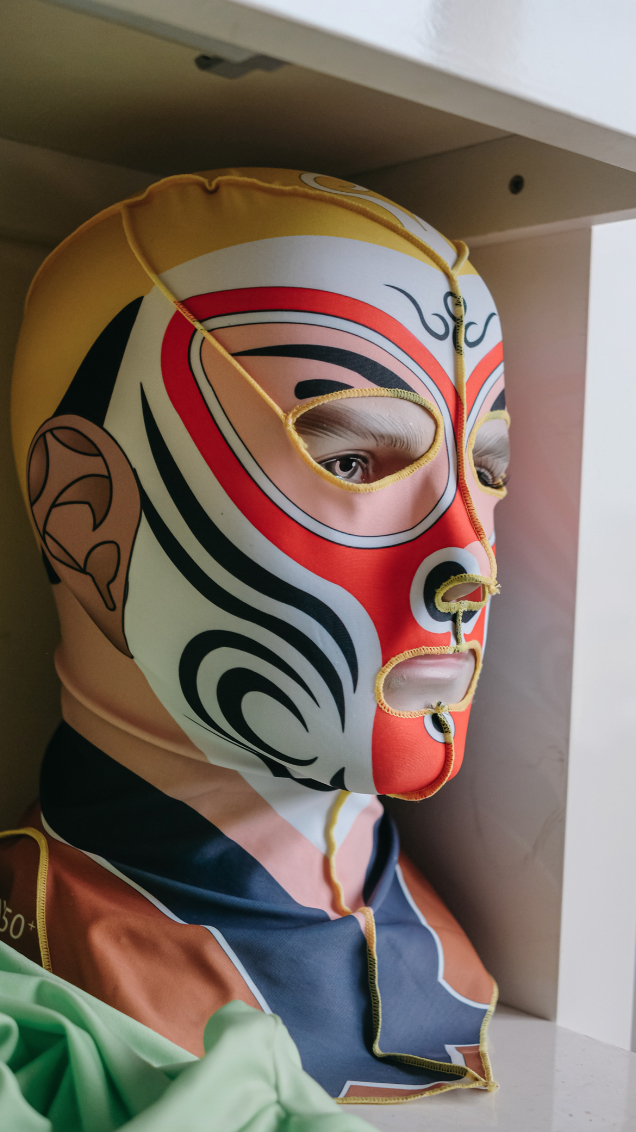

In 2004, the facekini was born. It was an extra layer of protection for the most important part of the human body: the head. Zhang studied ski masks and diving masks to develop a concept of a Lycra headgear that was suitable for swimming, and she spent years perfecting it. Today, different generations of facekini prototypes are neatly displayed in a corner of Zhang and Liu’s office.

These two designs are clearly the most cherished in the couple’s collection. They’ve even worked to create unique prints commissioned from local artists. Like the bodysuit, the facekini was first produced in plain colors, but over time they began including human features, such as eyebrows and hair. More intricate patterns also began appearing, many of which pay tribute to Chinese folklore and traditions, such as Peking Opera masks. An all-time favorite is a theme that takes inspiration from Uygur dancing costumes, featuring dangling gemstones as printed headpieces. It fills Zhang with pride. There’s also a collection themed after endangered animals that combines the facekini and bodysuit in one single piece.

The functional design of the facekini also evolved with time. Each summer, Zhang improved the product based on her observations and the feedback she received from her now loyal customers. For instance, the first generation only had four holes; two for the eyes, one for the nose, and one for the mouth. But then she added extra holes, including one to stick a ponytail out and two for the ears to fasten goggles and hold sunglasses.

When a huge public swimming pool opened in Qingdao, Zhang saw the demand for facekinis increase exponentially. It was only then that she realized that her invention had a multifunctional purpose. “People also like it because it protects them from the harmful rays of the sun. It’s just like wearing a hat—but this one doesn’t blow off in the wind.”

Unlike Western countries, suntanning is a developing practice in China, one that’s only recently gained momentum with the establishment of Hainan as a holiday destination and interest in surf culture. While more and more young Chinese aspire for bronzed skin as a symbol of a healthy and free-spirited life, it’s a distinctly different ideal of beauty for most of the population in China. Traditionally, not just in China, but in East Asia at large, pale skin is associated with a higher social status, while tanned skin associates an individual with working in the field, under the sun. Hence, mainly for women, white skin is still very much idealized as a standard of beauty.

Most of Zhang’s customers are middle-aged women living in the coastal cities of China who are keen on keeping their skin porcelain-white. It’s not unusual to see them at the beach with umbrellas, shawls, and hats—or in face-covering and head-to-toe designs that evoke imagery of Leigh Bowery—to protect from the sun. They’ve been flaunting their style on the beaches of Qingdao for several years with their facekinis, but they only caught media attention in 2012, when photos of the attire went viral. Shortly after, The New York Times published a front-page story about the surging trend in Qingdao, but the article didn’t mention Zhang, Liu, or their invention.

In 2014, there was a furor in the fashion world when Carine Roitfeld, the former editor-in-chief of Vogue Paris, ran a piece featuring models wearing designer swimsuits and facekinis in her own biannual magazine, the CR Fashion Book. The piece shocked most fashionistas, for they thought Roitfeld was endorsing the Chinese trend. If only they had actually read the editorial, they would have known that her intention was to highlight the opposing ideals of beauty and the contrast between East and West regarding tanning practices—raising no judgments. “In Asia […] a tan does not signify a chic trip to Capri, but it could mean hours of hard labor spent out in the harsh sun,” she wrote.

By then, countless international magazines had already reached out to Zhang and Liu for interviews. Zhang, however, was always hesitant in drawing too much attention to herself. She refused all interview requests until a close friend told her she had to take credit for her invention. She finally gave her first interview to a German magazine. Liu still has their cold email in his mailbox, which he shows to us on a dated desktop computer.

Ever since, they’ve given interviews to more magazines than they can remember. Zhang shows us the clippings of many articles about the facekini. As we flip through them, we see pieces in Japanese, Russian, Arabic, English, and what seem to be Swedish at a quick glance. It was the media that gave the facekini its famous name. Before, the product was simply called “face protector,” but the public fell for the buzzword in China and abroad. Nowadays, the term even appears in online dictionaries as a countable noun.

However, many of these publications didn’t feature Zhang’s facekinis. They featured copies with different patterns and structural designs. In fact, an American business executive copycatted the facekini and trademarked the name in the United States in 2013, right after it went viral. He was even interviewed by Inc. magazine. All this prompted Zhang and Liu to protect their concept legally, but there’s little they can do in international waters.

Also, as the facekini became a media phenomenon, mockery set the tone. The new product and Chinese beach culture at large came under the scrutiny of tendentious journalists. The facekini was a “terrifying trend,” a “Halloween prop,” a “hip of horror.” Some said that “bandit masks invaded the beach” and that the facekini was “fashion’s worst trip to the beach yet.”

Zhang remained oblivious to it all until the day she learned that a photograph of a Qingdao beachgoer wearing one of her designs appeared as part of a selection of shocking photos in an American magazine. Right next to it, a picture of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. “Of course, I had heard occasional comments about the way the facekini looked. And there were some isolated incidents of children getting frightened at the beach. But I always worked on my designs to keep them away from any negative associations, and I always thought of the facekini as something good, made to protect people. It was disturbing to me to see it related to something so negative.”

China also joined the international frenzy. Chinese netizens went wild with comparisons between the facekini and the burkini, especially when the latter was banned in some resort towns in the French riviera in 2016. Jokingly or not, there were calls for a ban of facekini on the basis that it could help the ill-intentioned conceal their identities.

Zhang found the accusations and comparisons preposterous. She says there’s nothing intrinsically evil about her invention. As with many other things, it’s how people use it that determines whether it’s harmful or not. She also says that the facekini is not religious nor mandatory. “You wear it if you want, and for whatever reason you want.” Still, she had to stay away from the internet for quite some time to avoid getting upset.

Despite the widespread obsession with the facekini, face-covering masks are nothing new. Balaclavas, for instance, were already worn by police, the Pussy Riot members, Mexican wrestlers, and fetishists alike. In parts of Southeast Asia, construction workers and motor cyclists commonly wear full-head accessories to shield themselves from the scorching sun. Still, Zhang was the one to re-imagine the accessory as a wearable device away from the purpose of concealing one’s identity and to make it both protective and fashionable.

Not to say that the international exposure did not benefit her business. She now exports facekinis to Japan, Australia, the United States, and England. She sells it to almost all Chinese provinces, including places far away from the coast, because some customers also like to wear facekinis to go jogging or trekking. Her company with Liu, Sturgeon Dragon, has about ten employees spanning product development, customer service, and logistics. Zhang is the inventor and lead designer, while Liu is more focused on the business, marketing, and public relations side. They’ve worked together for over twenty years, seventeen of those perfecting the facekini, a product that represents at least ninety percent of their business revenue.

Like the story? Follow Neocha on Facebook and Instagram.

Contributors: Tomas Pinheiro, Daecan Tee

Photographer: Mae Szeto

Chinese Translation: Olivia Li

Additional Images Courtesy of Peng Yangjun