What a skirmish at a Laos potash factory tells us about Chinese activity on the frontier

When the commodity frontier calls, entrepreneurs answer, and state policy follows.

On January 30, an attempt to disperse 30 or so Chinese workers demonstrating in front of the offices of Sino-Agri International Potash in Khammouane Province, Laos ended in gunfire.

No injuries were reported in the anodyne brief from local officials, which was picked up by local press (link in Lao). As the official report has it, workers from a Sino-Agri subcontractor were agitating for an increase in travel expenses. When police stationed at the mine office were dispatched to disperse them, workers grabbed their guns. Members of a provincial militia detachment fired into the air.

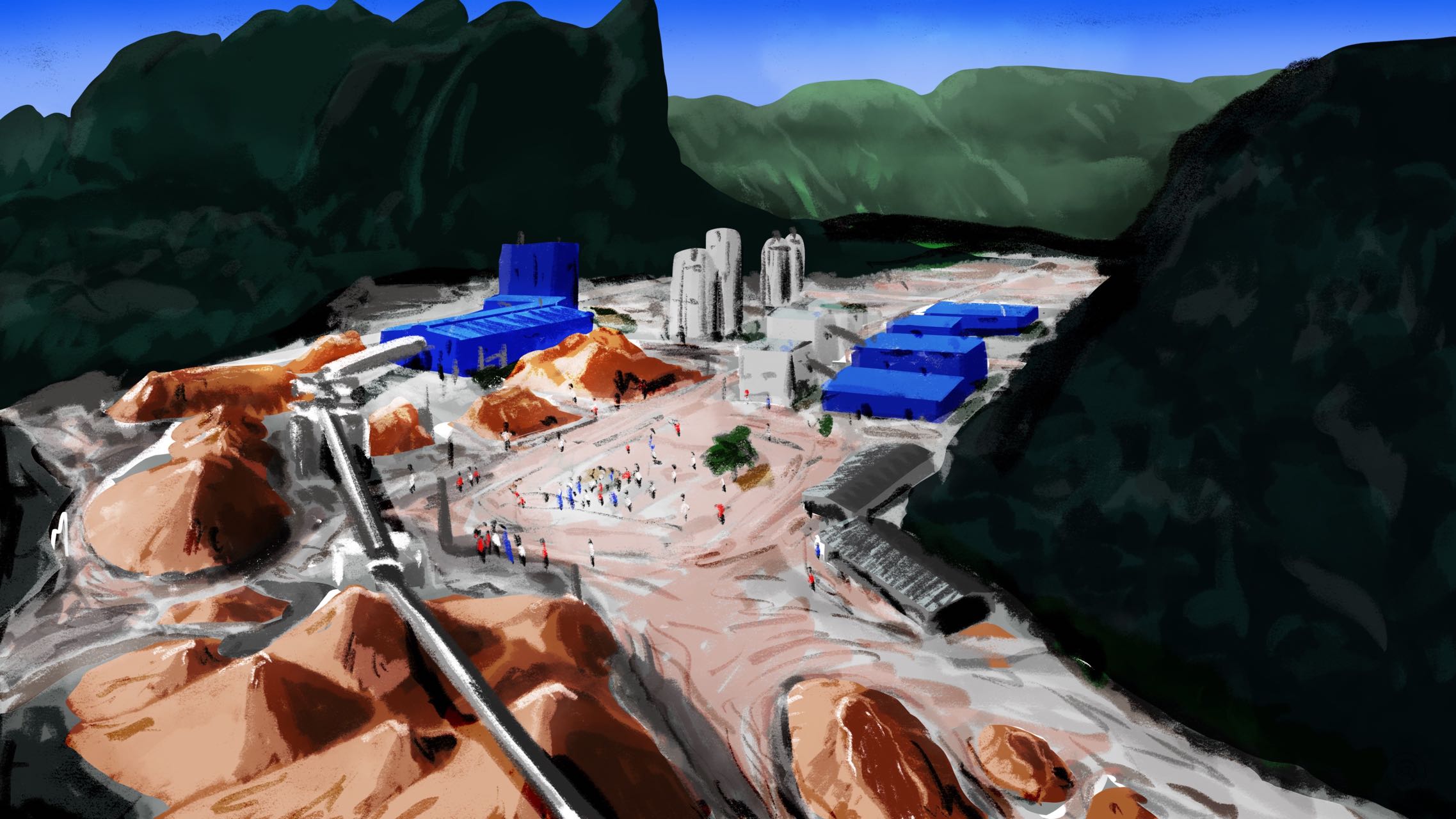

Shaky videos purporting to be of the incident seem to confirm this. In the background of the first, we can see the type of village that Chinese firms build on the frontier: a basketball court, cinder block dormitories, dirt roads, and a gleaming white SUV parked in a driveway. A man in a white T-shirt and a blue face mask is seen grabbing an AK-47 and running off camera. A man in a Lao police uniform gives chase, but pauses after a couple strides. That is followed by the sound of a rifle being fired. It sounds close. We can hear spent rounds jingling on the concrete. The shots probably came from the Lao militia men, as the report says.

In the second video, a few hotheads grab at the barrels of AK-47s slung over the shoulders of Lao soldiers in camouflage. A few men in Sino-Agri jumpsuits attempt to defuse the situation, but it appears to end with a company representative being swarmed and beaten.

It is unclear exactly how the protest was brought to a close. A fragmentary Radio Free Asia writeup (link in Lao) does not provide much additional detail, but confirms that the protest was over unpaid wages. The RFA report and the official statement differ on whether the protest was sparked by the construction subcontractor refusing to provide sufficient travel expenses or an ongoing issue with Sino-Agri not covering payroll.

The most basic question raised by the incident is what Chinese miners are doing in Laos.

Chinese companies pulling resources out of the ground in places like Laos are often understood as being participants in grand state strategy. This is a view of things promoted by Beijing and their rivals.

Looking closer at the operation of resource entrepreneurs in Khammouane, it’s unclear how they are contributing to the “win-win plan” of international development described by official media. They can’t be used as evidence of a neocolonial project led by the Chinese state.

Rather than being rationally directed by state planners, the global marketplace makes it profitable to send capital, migrant workers, and new technology to a commodity frontier. When we see state power being used, it is being leveraged by entrepreneurs to stay competitive with global competitors.

The miners in Khammouane and the sub-contractors building their dormitories and facilities or providing security are there because of global trends in commodity markets.

Commodity prices are a better predictor of Chinese frontier adventures than state policy.

Potash is expensive. Apart from an anomalous surge in 2008, it is more expensive than it’s ever been. As the price continues to climb, miners stand to make a lot of money.

Potash keeps the world fed. Along with nitrogen and phosphorus, it’s one of the key ingredients in commercial fertilizer. Without it, North Chinese farmers would struggle to grow wheat and soybeans. A disruption to the supply can be catastrophic. Peak fertilizer prices in 2008 exacerbated a global food price crisis. Current high prices for fertilizer are already causing hunger in Africa.

Most potash used in China is imported. When the global price soars, farmers in Heilongjiang pay about the same price as farmers in Indiana.

China manages strategic potash reserves through Sinochem, which they can release to control the price, but it’s in the interest of Chinese firms to keep fertilizer prices ticking upwards. They have significant stakes in the global potash market, having scooped up interests in industrial fertilizer operations in places like Belarus, Canada, and Jordan.

There are domestic deposits of potash, which began to be effectively exploited in the 1990s and 2000s. Operations in Qinghai, Xinjiang, and Yunnan produce around 10 million tons a year. Self-sufficiency is possible but domestic production capacity has plateaued since around 2014. It can be more expensive to ship potash from Qinghai and Xinjiang to northeastern provinces than to bring it in from overseas. Zero-tariff exports were introduced to spur production while not harming the interests of firms operating overseas. However, the country’s largest player, Qinghai Salt Lake Potash, has occasionally struggled to remain solvent.

Potash mines in Laos are not intended to reduce the price of fertilizer, secure strategic reserves, or give China a competitive edge. The output of the Laos mines can only account for a slim percentage of Chinese consumption. Some of their output is intended for export markets. The workers striking at Sino-Agri might have been producing potash intended for Indonesia.

The mines in Laos are marginal projects. They exist because of high fertilizer prices and leveraging of state resources. Sino-Agri can send potash into Laos or south to the Thai border only because of the China-Laos Railway.

The first train to depart for Kunming on the new line was loaded with Sino-Agri potash. A company representative said: “The opening of the railway will help boost the potassium production in Laos and its exportation.” The railway also makes it easier to take fertilizer south to Thailand and on to export markets. Fertilizer products from Yuntianhua’s joint ventures with an Australian firm can now be brought from the Lao hinterland to the Thai border in a third of the time (link in Chinese).

The commodity frontier calls, the entrepreneurs answer, and state policy follows.

The state doesn’t direct this expansion and can’t protect it, either. State power in the China-Lao borderlands, like the AK-47 rounds pumped into the humid air in Khammouane, is mostly symbolic.

Having Lao police or military stationed at your potash mine is another cost of doing business. Although the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party is in the midst of an anti-corruption drive, doing business with security forces, local officials, and state-owned enterprises requires tolerance for paying tolls.

The most successful Chinese businessman in Laos is Zhao Wei, whose business practices have earned him sanctions from American authorities. He runs casinos and hotels from a 40-square-mile concession purchased from the government. If the Department of the Treasury is to be believed, his Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone operates at the pleasure of his Wa State militia backers across the border. More legitimate money would be scared off by rumors of methamphetamine trafficking and barely regulated prostitution.

When necessary, Zhao Wei leverages state power, too: his lengthy battle with Khun Sa associate Naw Kham, which may have led to the Mekong River massacre, was ended by Chinese and Lao police.

Zhao Wei’s frontier entrepreneurship runs parallel to operations at Sino-Agri. Their potash mines contribute as much to the Belt and Road Initiative as Zhao Wei’s casinos or alleged methamphetamine trafficking, which is not very much — and not intentionally. They make use of state resources to varying degrees but are not directed by the state and frequently operate in zones of post-national sovereignty.

Chinese entrepreneurs have come to dominate commodity frontiers in Southeast Asia, Central Asia, and Africa. Bureaucrats in Beijing sign off on grand state projects, but their chaotic undertaking has more to do with potash miners in Khammouane. The drive to pull resources out of the ground rarely comes from state policy.