In the Global South, China is pitching its Ukraine stance as an antidote to Western hypocrisy

Amid the Ukraine war and the economic impact of massive sanctions on Russia, China is deftly connecting worries about international turbulence with Africa’s wider perception that it’s perpetually ignored. Here’s what that means for the future of China’s relations with the Global South.

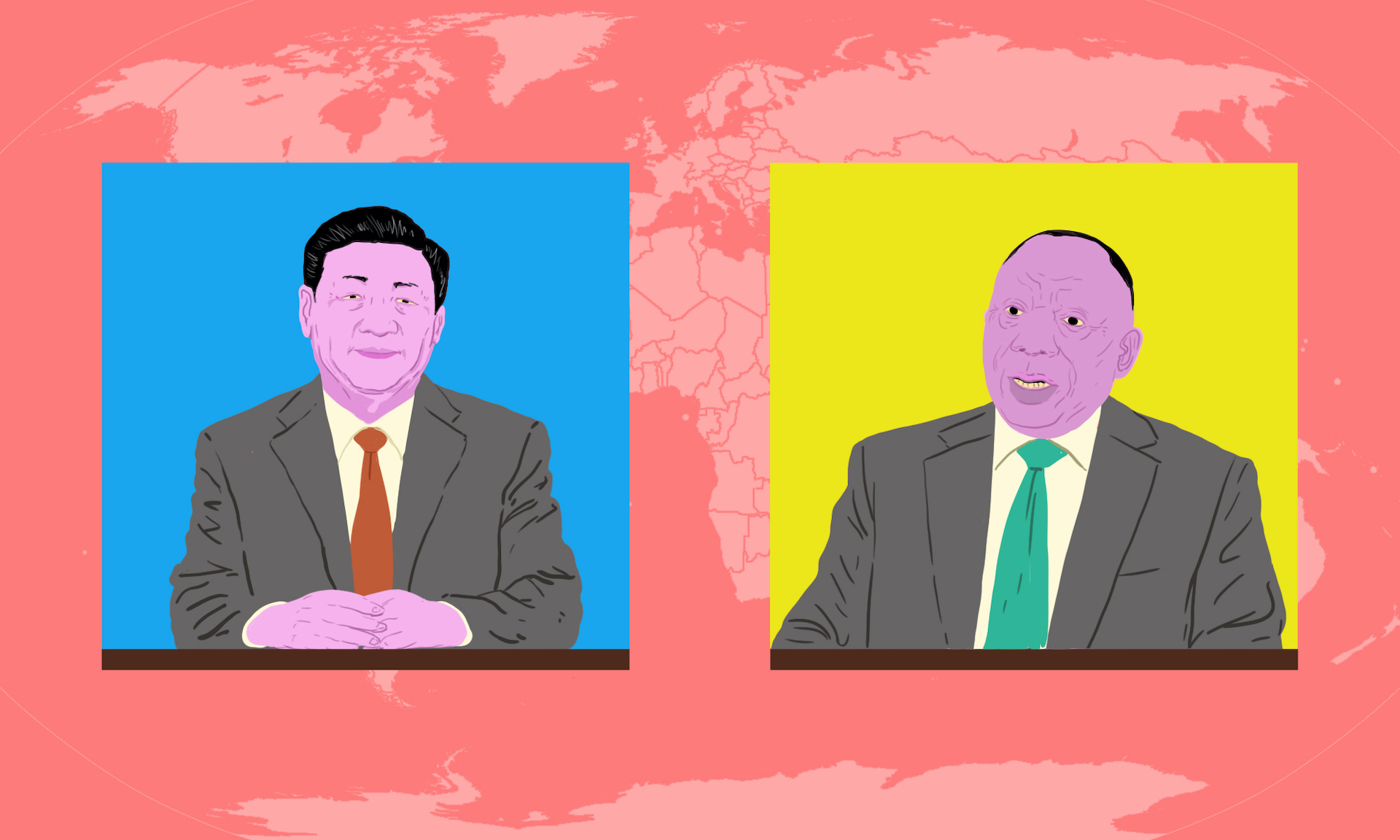

This weekend, Chinese leaders embarked on a diplomatic blitz. President Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 had a call with South African President Cyril Ramaphosa on Friday, and during the weekend, China’s Foreign Minister Wáng Yì 王毅 also met with counterparts from Zambia, Algeria, and Tanzania.

It’s no surprise that Ukraine featured prominently in these discussions. In fact, these meetings represent more than China’s usual African engagement. We’re arguably seeing a glimmer of how Beijing is repositioning itself in relation to the Ukraine crisis, and that it will crucially involve the Global South. This repositioning has three aspects:

- In the first place, China is trying to use broad statements in support of negotiations as a way to stake out a third position that relieves the pressure to be either pro-Putin or pro-NATO. After his meeting with Ramtane Lamambra, Algeria’s Foreign Minister, Wang Yi said, “We generally agreed that there are more than two options, namely, war and sanctions, for dealing with international and regional hotspot issues, but dialogue and negotiation is the fundamental solution.”

- Second, China is trying to reframe the debate from solidarity in the face of aggression toward the economic impact that this solidarity (in the form of massive sanctions and mangled supply chains) will have on the global economy. China of course has its own sanctions-related preoccupations, but it has managed to hook them to the Global South’s worries about paying for a conflict far away with spiking bread prices in its own countries. Wang Yi deftly connected these concerns with Africa’s wider perception that it’s perpetually ignored, stating, “The more turbulent the international situation is, the more attention should be paid to the voices of African countries, and the more support and assistance should be provided to Africa.” Not to sound cynical, but if that’s your message, you’ll always find a receptive audience in Africa.

- Third, Beijing seems to be wagering that whatever outrage certain Global South constituencies feel about Russian aggression, this will be sufficiently diluted by wider misgivings about Western double standards to at least give its third position some political legs. This is arguably the most potent part of the strategy, and the one Western countries trying to build solidarity on Ukraine will find the most troublesome.

Take South Africa. President Cyril Ramaphosa echoed China’s call for negotiations. As the public intellectual and radio personality Eusebius McKaiser recently pointed out, the position makes no sense in the face of naked aggression from Russia, explaining, “It is premised on the false belief that Russia and Ukraine carry equal responsibility for the invasion.”

But McKaiser’s frustration with Pretoria’s position isn’t shared broadly. For example, on March 3, Riina Kionka, the EU ambassador to South Africa, tweeted “We’re still scratching our heads over here at Team Europe” about South Africa’s abstention from the UN vote. She received many clapbacks, for example: “Please continue scratching. It’s 28 years post-apartheid and we’re still scratching our heads as to how the biggest beneficiaries of apartheid including corporates didn’t receive the kind of sanctions seizures European countries are executing on Oligarchs. Palestine says hi btw.”

This resistance goes all the way up to the government. Clayson Monyela, the head of public diplomacy in South Africa’s Department of International Relations and Cooperation, tweeted in response: “#whataboutism Let’s not forget the People of Palestine, Yemen, Syria, Libya, Somalia etc. The EU should ‘condemn’ aggressors in these cases as well.”

China’s emerging position seems to shrewdly hone in on twin Global South resentments: of the economic fallout from Western sanctions, and of Western pressure as a whole, no matter the specific merits of the case. This weekend, Xuē Bīng 薛冰, China’s new special envoy to the Horn of Africa, struck this note, too, saying: “Some Western countries come here and tell you what and how to do it. From our discussions, I have a feeling countries are fed up with that.”

China’s call for negotiations, combined with vague condemnations of outside pressure on countries, is increasingly cohering into a third position on Ukraine, one that offers Global South countries a set of talking points to both stay out of a faraway conflict and to avoid fights with anti-Western factions at home. There are signs this strategy is working in Africa and beyond.

This position may well be rooted in little more than China’s own anxieties about new forms of Western sanctions, but that doesn’t lessen its impact on the Western campaign for global solidarity on Ukraine. This is because it taps into the West’s most formidable opponent: its own history in the Global South.

This commentary was originally published by the China-Africa Project, and is republished here with permission.