What do Taiwan residents really think about independence?

“The status quo feels safe, but I’m not sure it’s what people actually want.”

For Taiwan, what does it mean to be independent? The answer isn’t straightforward.

“Republic of China (ROC) independence,” or huádú 华独, refers to a state of de facto independence under the ROC constitution. President Tsai Ing-wen’s (蔡英文 Cài Yīngwén) Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) points to Taiwan’s current government as evidence that they are already independent from the People’s Republic of China, and for years, the popular understanding was that this “status quo” is what the majority of Taiwan residents want to maintain.

Alternatively, supporters of “Taiwan independence,” or táidú 台独, believe in de jure independence, and advocate for changing the ROC constitution and the country’s official name to “Republic of Taiwan.” Beijing is unequivocally opposed to this stance, as formally recognizing Taiwan as a separate state would break from the One China principle.

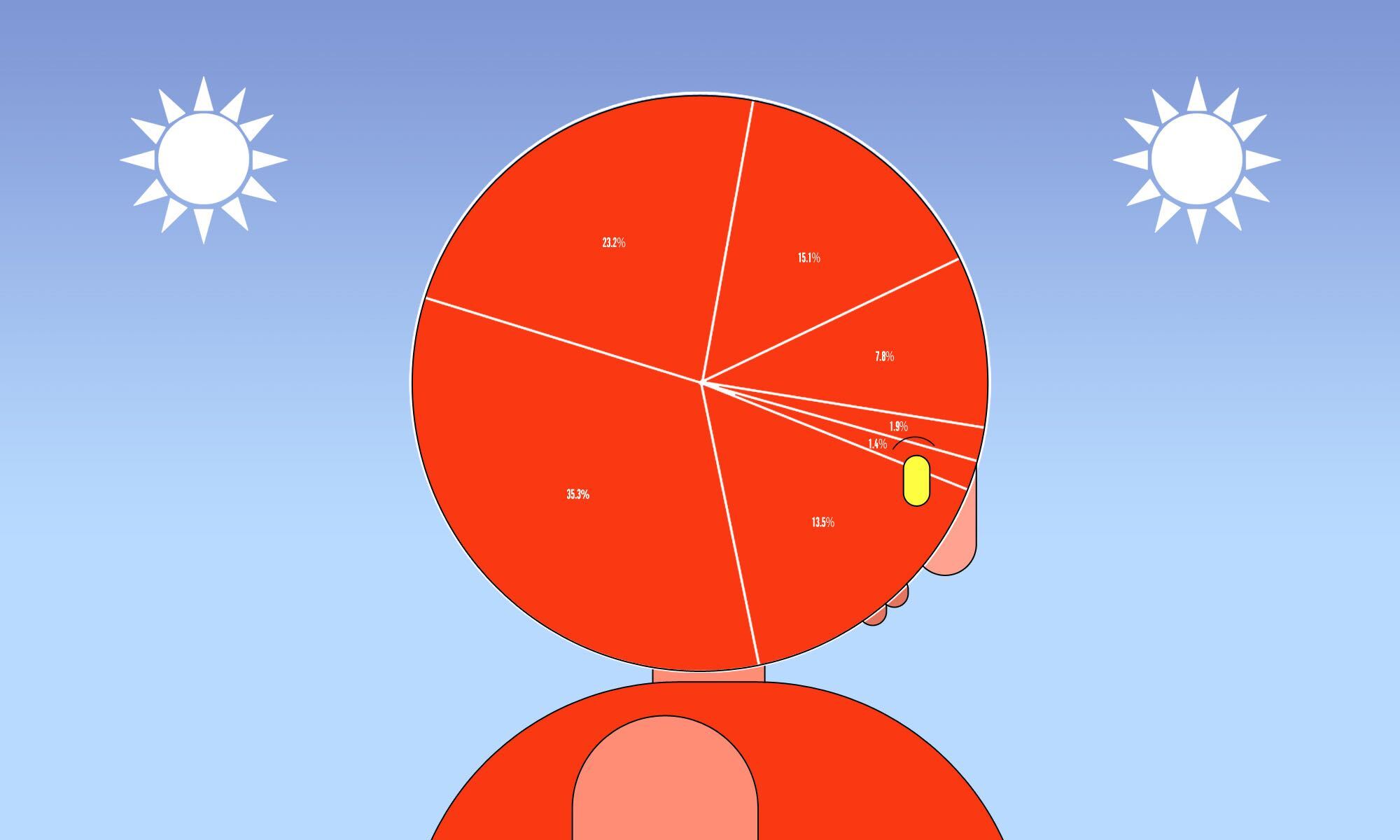

However, there is evidence to suggest that more and more people in Taiwan are moving into this camp. After results of a June 2020 poll from the Taiwanese Public Opinion Foundation were released, foundation chairman Michael You (游盈隆 Yóu Yínglóng) said, “In my research on public surveys on these issues over the past 30 years, this is the highest rate of support among Taiwanese for independence. It is also the lowest figure for people supporting unification with China.” More recently — just last month — You directly challenged the results of polls that say people favor the status quo.

A distinct identity, a sovereign country

There is a widening cultural chasm between Taiwan and the mainland, reflected in the popular attitude toward “independence.” “(De jure) independence means nothing to me,” said 43-year-old Jessie Huang (黃潔西 Huáng Jiéxī), a business development consultant in Taipei. Pointing to the ROC flag, her ROC passport, and the New Taiwan Dollar currency, Huang laughed. “It’s quite funny to me when people talk about independence. Taiwan is already a country, we don’t need to use the word independent. What would we be independent from?”

But this line of thinking wasn’t always the status quo. In the past, when Taiwanese people felt more Chinese, there was greater affinity for reunification. “My grandparents don’t mind if you call them Chinese, because they came to Taiwan from there,” journalist Tang Chia-yi (唐家儀 Táng Jiāyí), 27, said. When the Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, KMT) fled to Taiwan in 1949, they brought the ROC government with them, and the promise to eventually retake the mainland.

To this day, the KMT maintains the One China principle, but dispute Beijing’s view that the PRC is the legitimate government of China. Although the KMT is no longer in power in Taiwan, many of their supporters, such as Tang’s grandparents, still support unification with the mainland.

But younger Taiwanese no longer identify in the same way as their older kin. “We get angry when people say we are part of China,” Tang said.

Fierce defense of Taiwanese national identity can take on nasty undertones on social media. When speed skater Huang Yu-ting (黃郁婷 Huáng Yùtíng), one of the four athletes representing Taiwan at the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, posted a training video on Facebook wearing a Chinese national team suit, she received caustic blowback from Taiwanese online users.

Although she took down the video after the backlash, Huang refused to acknowledge the issue, which further emboldened what she called “trolls and haters” to attack her. As quoted by the Taipei Times, one of the comments on her post said, “You should be thanking Taiwanese, as their taxes paid for your training, but instead you betrayed them.” The Taiwanese Sports Administration later cut Huang’s funding for two years in a further official condemnation of her attitude.

For some, consistently questioning Taiwan’s future is a futile endeavor. Lù Pèi-róng 陸姵絨, 31, a vegan baker from Kaohsiung, noted that despite Taiwan’s democracy, the island’s political status has never been in the hands of the Taiwanese people. “I prefer to focus my efforts on local issues such as the environment, waste and food industry issues,” Lu said. “These are issues I can stand for because I know about them and believe in them.”

Huang was similarly nonchalant when discussing the recent uptick in Chinese military threats to the island. Commenting that there is no use getting stressed about it, she said, “We know there is a threat, but what can we do? We can’t really do anything about it.”

Meanwhile, Tsai’s administration passed a spending bill in January to inject an additional $8.6 billion into the Taiwanese military. Recent calls to extend the period of compulsory conscription from four months to one year have emerged in an effort to bolster the island’s defenses, while civil defense preparations in the form of workshops and civilian handbooks have gained fresh momentum in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The status quo compromise

Tang’s family has long sided with the pro-unification KMT, but despite voting for Tsai’s DPP in 2020, she has become disappointed in how the administration functions. Tsai, she said, “is good at cultivating a popular public image, but there have been some decisions I disagree with.” One of them, Tang noted, was the National Communications Commission’s decision to remove the broadcasting license of pro-China Chung T’ien (CTi) television channel in 2020.

Tang feared that the current administration has been weak, but has demanded support through parochial actions. “The NCC decision was controversial because it did not allow freedom of speech,” Tang explained. “My dad and grandma were so angry when the channel was closed down. Most of my green-voting friends were happy about the decision, but to me, blocking freedom of news is autocratic.”

Despite the channel’s repeated violations of disinformation regulations, Tang defined the crushing of dissenting voices as a hallmark of authoritarian rule that led her to question what the DPP, and in turn the ROC, stands for. But for all her malaise, Tang has no intention to change how she votes.

Tang is not the only one to compromise with the DPP’s vision for Taiwan. Yang Mei-lin (楊美林 Yáng Měilín), a 29-year-old social worker from Taoyuan, pointed to potential discrepancies between survey results and true public opinion, stating, “The status quo feels safe, but I’m not sure it’s what people actually want.”

Acknowledging that, like Tang, dissatisfaction does not always lead to political action, Yang reported seeing increased accusations of Tsai not being assertive enough on cross-strait relations. There are young people, Yang said, now looking for “smaller and more radical independence parties for more structural change.”

One such option is a left-wing vision of Taiwan independence that aims to re-conceptualize Taiwan’s current political system. “We need to acknowledge that the KMT existed not as a neutral force that took over Taiwan when the Japanese left, but it was actually a colonial regime that instituted a lot of ideas that we still have today,” scholar and LGBTQ activist Liú Wén (劉文) explained.

Despite Taiwan’s reputation as a bulwark of liberalism in Asia, supporting the abolition of the death penalty and legalization of same-sex marriage, Liu pointed to shortfalls in labor and citizenship rights among minorities. Instead, she stands for a vision of Taiwan independence that acknowledges the colonial and authoritarian roots of the ROC state apparatus, working toward a future “that provides LGBTQ justice, indigenous rights, and pays more attention to Taiwan’s multicultural and multi-ethnic society.”

More than a national or even ethnic project, Liu voiced the desire to reconstitute what Taiwan could be. “We do not see Taiwan independence as an end goal in itself, but as something that should be continuously worked toward,” Liu said.