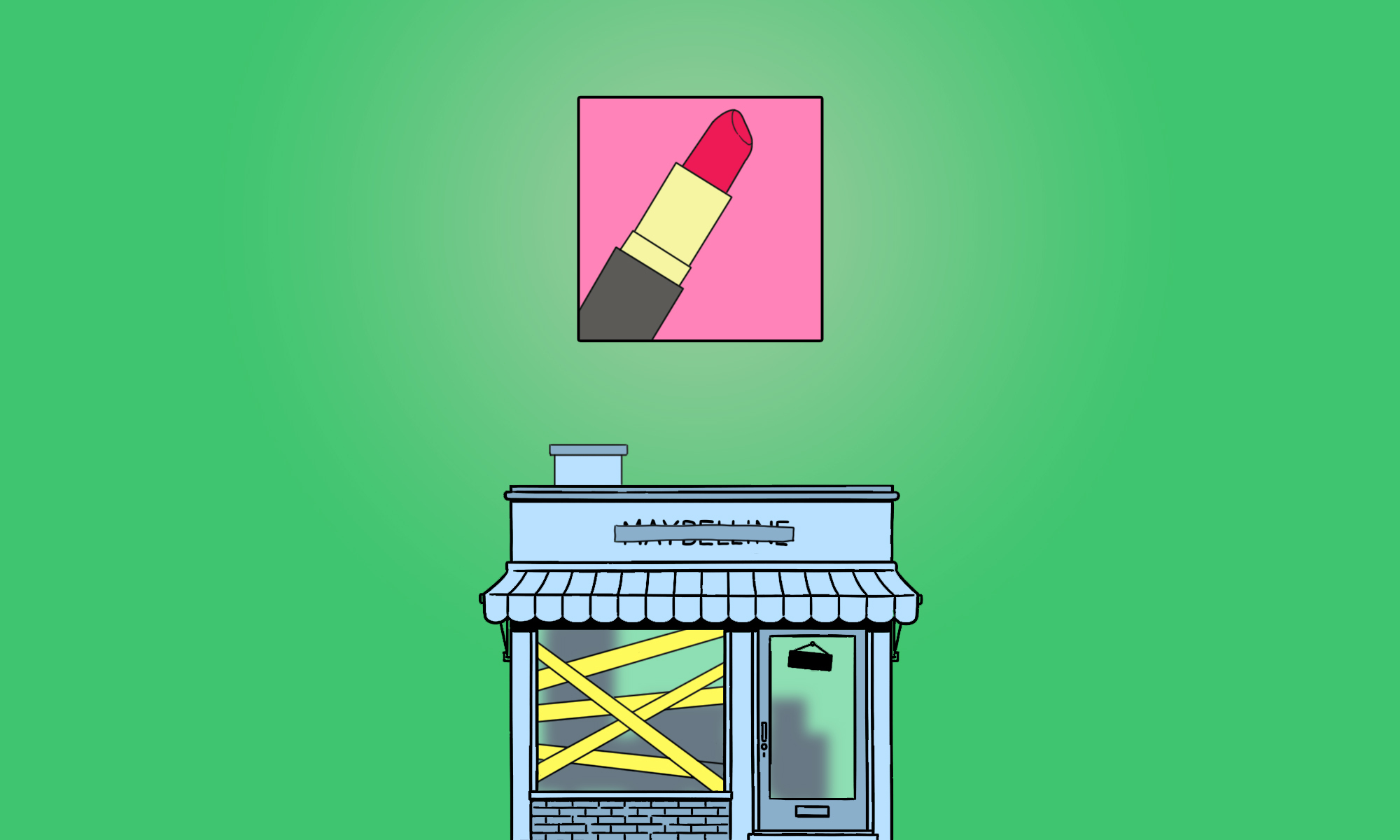

Why is Maybelline closing its brick-and-mortar stores in China?

Once a beloved makeup brand in China — known for its affordable products and glamorous image in advertising campaigns — Maybelline’s business model in the country is being tested by growing local competition and rapidly changing demands from increasingly sophisticated consumers.

For generations of Chinese women, the American cosmetics and skincare brand Maybelline epitomized a certain kind of aspirational New York cool.

When the L’oreal-owned company made its foray into the Chinese market in 1997, it was one of the first Western beauty brands to introduce makeup as an everyday glow-up tool to Chinese consumers. In the following years, glossy commercials for Maybelline were unavoidable on Chinese television, and its iconic tagline — “Beauty comes from within. Beauty comes from Maybelline New York” — were ubiquitous at department stores and its standalone shops.

That sight, however, will soon be relegated to history. Last week, after a flurry of reports emerged in the Chinese press, Maybelline confirmed that it was going to shutter all of its physical locations in China, adding that the closures would occur in phases and that it’s pivoting to online sales as part of a major adjustment to its business model.

The news comes on the heels of Maybelline trying to revamp its brand image in the past few years to make itself seem more high-end and sophisticated to Chinese shoppers. But the restructuring also signals how hard it is to turn around a struggling brand in the ever-growing and fast-paced beauty industry in today’s China, which is estimated to be worth $78 billion by 2025.

In a statement to Women’s Wear Daily (WWD), a fashion industry trade journal, a spokesperson for Maybelline cited a need to “adapt to the changes in the market and consumer demand” as the reason for the scaling back of its physical presence in China, writing that although the decision would affect nearly 80 stores across the country — with some underperforming ones being shut down imminently and others being gradually phased out as their leases expire — Maybelline products will still be sold at around 10,000 brick-and-mortar drugstores, as well as on ecommerce sites like Tmall and JD.com.

“Starting from 2020, Maybelline New York in China has gradually carried out the strategic transformation from traditional channels to Online + Offline channels, thus bringing consumers a diversified and interactive beauty shopping experience,” the spokesperson said.

The end of an era

The news wasn’t entirely unexpected. In May 2018, in a strategic move to adapt to the online shopping trend that was sweeping across China, Maybelline announced a full withdrawal from supermarket chains such as Carrefour and Walmart. Two years later, as the COVID-19 pandemic battered China’s retail sector, the company began leaving department stores in cities like Shanghai and Beijing.

“They have really lost appeal to Chinese consumers because of their limited innovation capabilities, their focus on hero products that made them completely dependent, and the rising competition of domestic brands,” said Steffi Noel, research director at the Shanghai-based Daxue Consulting. “And COVID did not help for sure.”

“All those blue-eyed, blonde-haired supermodels in its advertisements were spokespeople for Maybelline,” recalled Tia Han, 42, who remembers seeing a Maybelline commercial for the first time when she was a college student in Guangdong province. “Seeing these glamorous women stare straight down the lens as they walked on the busy streets of New York was exhilarating.”

“They had the most extravagant display in cosmetic sections at department stores,” Han added, recalling purchasing her first mascara from Maybelline and the excitement of applying it when she returned to her college dorm. “At the time, there weren’t many beauty brands on the market, so it was like, if you were a makeup beginner, chances were you would get your first makeup product from Maybelline. Its ads were everywhere.”

Founded in 1915 by LGBTQ makeup pioneer Thomas Lyle Williams, Maybelline got its start with a lash and brow product, and later developed a reputation in the beauty business for its sensibly-priced, accessible, and diversified product line. In 1996, the company, which was the third-largest U.S. maker of beauty products at the time, was acquired by French cosmetics giant L’Oreal in a deal valued at $660 million. The purchase further solidified L’Oreal’s domination of the global market, where it now stands as the world’s largest cosmetics company by revenue.

When Maybelline entered the Chinese market in 1997, it was a highly strategic move, said Noel, because “Chinese makeup users were highly influenced by the Western culture, and particularly American culture.”

“The upper class in Tier 1 cities just started to regularly travel overseas and became familiar with international brands. Arriving with the name ‘Maybelline New York’ was the perfect fit,” she added. “Additionally, the brand always sold quite affordable makeup products, meaning that it could easily target not only the upper class, but general makeup buyers influenced by American culture.”

Noel’s analysis rings true to Han. For her, “high-quality products sold at affordable prices,” coupled with Maybelline’s professional, premier image, were what drew her to the brand in the first place, she said. For years, she had Maybelline as a makeup staple on her vanity desk — just like millions of other women in the country.

With little competition, the late 1990s and early 2000s were the boom years for Maybelline in China. At its height, the company operated more than 5,000 stores and counters in department stores across almost 130 cities. In 2011, Maybelline’s market share in China was 15.71 percent, roughly three times that of its closest competitor. It remained the best-selling cosmetics brand in China until 2019 — but these numbers belied the increasingly narrowing gap between Maybelline and its rivals.

The rise of C-beauty

A confluence of factors has contributed to Maybelline’s slow demise in the country, where it now rarely cracks the top 10 in best-selling cosmetics brands on popular ecommerce sites like JD.com and Alibaba. In 2016, a major shift in China’s cosmetics landscape happened when the government changed tax rules for beauty products in an effort to stimulate domestic spending and help prop up slowing economic growth. With “the consumption tax on non-luxury beauty and makeup products plunging to zero,” Deloitte wrote in its industry forecast, Chinese firms “may get more of an opening, as price differentials will increase between foreign and domestic brands.”

The prediction became reality. In the next few years, a crop of local makeup companies led by Perfect Diary and Florasis emerged to give their foreign competitors a run for their money. In 2020, despite a drastic drop in Western beauty-industry sales caused by the pandemic, Chinese beauty brands generated several billions of dollars in revenue, accounting for half of the total cosmetics market in the country, according to a recent report released by consulting agency Fabernovel.

With their nimble product offerings, sensitivity to local consumer demands, and prowess in social marketing, Chinese makeup firms have outperformed their foreign counterparts on almost all fronts. Much of their success relies on their proximity to local factories, which allows them to conceptualize, launch, and manufacture a product line within a period as short as three months.

Riding a wave of interest in China’s cultural heritage known as guócháo 国潮 — literally “national tide” — Florasis, founded in 2016 as a direct-to-consumer brand in Guangzhou, is a breakout star among this cohort of Chinese makeup companies. Known for its “Chinese-style” cosmetics that resemble the looks of beauty items used by imperial concubines in ancient China, Florasis reported sales of 3 billion yuan ($443 million) in 2020, more than double the prior year’s 1.13 billion yuan ($167 million).

“Based on price positioning, the main competition of Maybelline now comes from domestic brands and Asian brands. Judy Doll, Perfect Diary, 3CE, or KissMe are all producing affordable makeup products,” Noel said. “Their products are innovative in terms of format and are also investing massively in packaging. The final products almost look like premium makeup products. Maybelline has real difficulties to follow up the pace and innovation capabilities.”

Struggling to attract young shoppers, C-beauty’s main customer base, Maybelline revamped its advertising strategy in the past few years. In an attempt to look hip and relatable, the company dropped foreign supermodels in commercials and hired a series of Chinese celebrities as the face of the brand. But the makeover seemed to have yielded little result.

“I really don’t know much about Maybelline as a brand. My impression is that it’s a decent starter brand for makeup beginners and it’s classic,” said a soon-to-be college student who goes by the name of taetae on Chinese social networking and ecommerce app Little Red Book. In July, after reading a plethora of product reviews on the app, taetae splurged nearly 6,000 yuan ($887) on her first comprehensive makeup kit from Maybelline. A mix of the upscale and the affordable, the local and the foreign, the set consists of over 20 items, including a foundation primer and an eye makeup remover.

“I saw positive reviews of those two products so I bought them. It’s as simple as that,” taetae said of the two cult-favorite products from Maybelline. However, considering herself a customer with no brand loyalty, taetae said that she wouldn’t mind switching to a different brand if her financial situation changed. “If I have more money, I will probably go for more luxurious makeup brands. And if I’m tight on budget, I’m sure I can find decent alternatives from Chinese beauty brands.”