Bolsonaro vs. Lula: What’s at stake for China in Brazil election?

Brazil is holding a historic presidential runoff on October 30. Here's what a win for either candidate will mean for the Brazil-China relationship.

The world will be watching on Sunday as Brazilians head to the polls to cast their vote in the second-round runoff of a historic presidential election. The battle between left-wing former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and right-wing incumbent Jair Bolsonaro has been exceedingly bitter and divisive, with each candidate perceived by the other side as a disaster for Brazil.

The mononymous Lula, the Workers’ Party candidate, is running on a promise to bring back the golden years of his 2003-10 presidency, when the Brazilian economy boomed and international expectations were high. He has pledged to tackle hunger, and stands for more progressive social and environmental policies.

In the other corner, Bolsonaro is a uniquely Brazilian incarnation of familiar far-right populism, uniting agribusiness, evangelicals, and the armed forces with his ultra-conservative promises to defend “God, family, homeland, and liberty.” While Lula believes in the state as an engine of economic growth, Bolsonaro puts his faith in free market capitalism. The latter, much like Donald Trump did pre-election, has also hinted at rejecting the election results if they don’t go his way.

Neither candidate has made China a big talking point in his election campaign, but you can bet that they will have differing approaches to China while in office.

Why does Brazil matter for China?

Representing roughly half of South America’s landmass, population, and GDP, Brazil is China’s most important partner in Latin America.

In 2020, Brazil was China’s sixth largest source of imports overall, its fifth for crude oil, second for iron, and first for soybeans. This last commodity is particularly important considering the only other significant source of Chinese soybean imports is the United States. Trade drives the economic relationship, but Brazil also hoovers up roughly half of Chinese investment in Latin America. According to a new report by the China-Brazil Business Council, Brazil was China’s number one destination for investment in 2021 globally.

Brazil also joins Russia, China, India, and South Africa in the BRICS, a group that Beijing hopes to expand as a counterweight to the West. If Lula wins the upcoming election, his victory will be the latest in a string of victories for left-wing candidates in Latin America. Against the backdrop of U.S.-China tensions, this renewal of left-wing politics will inevitably be read by some commentators as a rejection of U.S. hegemony.

Which candidate would Beijing prefer?

Chinese media has largely kept quiet on this issue. According to (in Chinese) Niú Hǎibīn 牛海彬, deputy director at the Shanghai Institute for International Studies, “Brazil will continue to maintain friendly and cooperative relations with China” regardless of who wins the election. This official line is a pragmatic and diplomatic non-answer, but it’s not completely untrue.

Bolsonaro’s anti-environment stance, aversion to multilateralism, and contempt for any world leader who isn’t a right-wing populist have made him a reviled figure in much of the West. He probably doesn’t have many fans in Beijing either — his anti-China rhetoric in 2018, when he was running for president, stoked concern among Chinese diplomats, but four years of good economic relations have calmed nerves in Beijing. If he won re-election, Beijing would send polite congratulations and settle in for four more years of solid economic cooperation.

Still, Lula is a friendly face, and it would be a surprise if Chinese diplomats aren’t secretly hoping for his return. Behind the scenes, Karin Costa Vazquez, senior fellow at the Center for China and Globalization in Beijing, says that most of her Chinese colleagues are rooting for Lula: “Virtually everyone I engage with here is hoping that Lula wins. While this doesn’t necessarily reflect the views of their institutions or the government, there’s a sense he’d be more open-minded to cooperation.”

What are the candidates’ actual positions on China?

The candidates are fighting tooth and nail, which means there has been precious little room for serious discussion of foreign policy, let alone China. “It’s such a low level of campaign, there’s no real policy discussion at all,” says Isabela Nogueira, coordinator of LabChina and professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. “But both candidates have served as president, so we can at least project based on what we’ve seen so far.”

Bolsonaro’s record: Bark worse than his bite

Bolsonaro’s political base harbors anti-China sentiments, but he also answers to powerful business interests. He’s pragmatic enough to not derail cooperation with China.

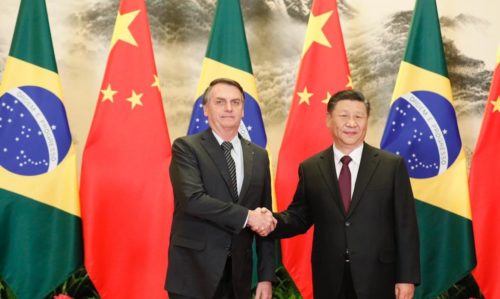

On the campaign trail in 2018, Bolsonaro put the U.S. at the center of his foreign policy and adopted populist, anti-China positions reminiscent of Trump, whom Bolsonaro has called his “idol.” Bolsonaro visited Taiwan in February of that year, and in the run-up to the election angrily denounced China as a predatory economic power.

But economic realities and powerful domestic interest groups made it impossible for Bolsonaro to deliver on his anti-China rhetoric once in office. “Agribusiness in particular made it clear to Bolsonaro that you cannot turn a blind eye to China,” says Vazquez.

Speaking in Beijing after inviting Chinese companies to participate in a Brazilian offshore oil auction, Bolsonaro said in October 2019, “Today we can say that a significant part of Brazil needs China, and China also needs Brazil.” As if to illustrate his point, the only international firms that ended up bidding in the auction were Chinese. In January 2021, Bolsonaro was even forced to backtrack on his opposition to Huawei’s participation in auctions to roll out 5G in Brazil.

Bolsonaro’s anti-China rhetoric never completely dissipated. Bolsonaro repeated Sinophobic conspiracy theories about the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic, and his son, Congressman Eduardo Bolsonaro, became involved in a Twitter brawl with the Chinese ambassador after he tweeted about COVID-19 that “the blame is with China and freedom is the solution.” But this antipathy toward China never made a real dent in the economic relationship between China and Brazil. During Bolsonaro’s tenure, trade figures hit record highs and Brazil remained the main destination for Chinese investment in South America.

Lula’s record: Strategic partnership

During his time in office from 2003 to 2010, Lula embraced China as a strategic partner in his efforts to reform the international order.

Lula oversaw an intertwining of China and Brazil’s economies, with China becoming Brazil’s largest trading partner in 2009. Although Lula can’t be credited with the 2000s commodities boom that drove this dynamic, he did steer the relationship, creating the High Level Sino-Brazilian Commission in 2004 and meeting with his Chinese counterpart Hú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛 eight times while in office.

But what distinguishes Lula’s record is the politics of his China policy. At the start of his mandate in 2003, Lula made the strategic decision to draw closer to China, and he framed his first trip to Beijing in 2004 as the most important foreign visit of his presidency.

Lula was elected as a man of the people, and he applied his politics of social justice to international relations. He sought to “redefine Brazil’s place in the world” by creating a more muscular Brazilian foreign policy and by attempting to reform what he saw as an unjust international order. By forging deeper connections with other countries in the Global South, Lula hoped to “construct a new world geography” that gave more room to voices from developing countries. This sentiment fueled the creation of the BRICS grouping in 2006, combining the major emerging economies of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and later South Africa.

“Lula had this vision that it was in Brazil’s interests to build a more multipolar world with a connection to everyone, but mainly China,” says Nogueira, professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. “It was strategic: they were trying to build policy space in relation to the United States.” China, as the world’s largest developing country, was key to Lula’s mission of reform. Lula saw Brazil and China on a semi-equal footing, as “great countries” that could together “change unfair rules” and cooperate “within an “international system marked by inequality.”

If Bolsonaro wins:

Continuity and business, but not much goodwill

“Bolsonaro doesn’t like China, but he’s forced to accept reality,” says Maurício Santoro, author of Brazil-China Relations in the 21st Century and professor at Rio de Janeiro State University. This combination of personal antipathy and pragmatic acceptance has resulted in a laissez-faire China policy that lets the economic realities of Brazil-China relations speak for themselves. Much of the work on deepening ties has been done by state governments or by business organizations, with neither interference nor much encouragement from the federal government.

According to Nogueira, “China policy under Bolsonaro runs on autopilot, guided by short-term agribusiness interests.” A second term for Bolsonaro means continuity in China policy. That’s good news for business, but a disappointment for those seeking to expand cooperation with China.

“If Bolsonaro wins a second term, we can expect more of the same — continuing trade and investment, but not much progress on other fronts,” says Vazquez, the senior fellow at the Center for China and Globalization.

There is one school of thought that believes Bolsonaro’s reservations toward China would disappear entirely if he won a second term. Bolsonaro’s relationship with the United States has cooled since Trump left office, and his alienation of Western leaders has deepened relative dependence on China. Whether or not Bolsonaro actually factors this into his strategic thinking, Beijing will be aware of Bolsonaro’s vulnerabilities. The Valdai Club, a Russian think tank associated with Vladimir Putin, makes the slightly absurd argument that Bolsonaro has become more enthusiastic about BRICS in part because he is “worried about the inclusion of environmental issues in the NATO agenda.”

Lula would be Beijing’s preferred partner, but there might be a silver lining in Bolsonaro’s isolation from the West.

If Lula wins:

A Lula victory warrants a slightly closer examination. Lula is leading in the latest polls, and though he’s spent longer in the Palácio do Planalto than Bolsonaro, it’s more difficult to predict how he’ll behave this time around. While Bolsonaro marks continuity for China, Lula’s third term would signal a new direction.

An old friend of China returns, but what does that mean in 2023?

Bolsonaro is famous for eating alone at the Davos World Economic Forum and being bumped out of G20 photo shoots, whereas Lula is the man that President Barack Obama once called the “most popular politician on earth.” For many China analysts, having Lula back means having a constructive, active foreign policy again, and that can only be good for ties with China. That perception is underlined by Lula’s record as an “old friend” (Chinese) of the Chinese people.

Economic realities might not change much under Lula, but the Workers’ Party is sure to strengthen the political dimension of the relationship, with a focus on BRICS and South-South cooperation. China analysts in Brazil are hoping that under a more proactive China policy, ties will expand into cultural and scientific domains.

There are also hopes that more pro-China signals from the administration will help move the dial on sticking points in the economic relationship, such as Chinese barriers to higher-value Brazilian exports. Although economic ties have grown under Bolsonaro, the hope is that with greater political will, the China-Brazil relationship could mean even more. “If we have a competent foreign policy, have more of a strategic eye, we can tie up geopolitics with economic deals — this is the sort of thing I could expect from a Workers’ Party government,” Nogueira says.

However, relying on Lula’s record to predict the future is dangerous: the 2020s are very different from the 2000s. Lula’s official government program calls (Portuguese) for the strengthening of BRICS, the return of Brazil to “global protagonist status,” and the “construction of a new global order committed to multilateralism.” But as Vazquez points out, while Lula’s promises might not have changed, times have moved on: “On foreign policy, Lula’s government program feels like a document from the 2000s, but this past doesn’t exist anymore — these concepts need to be updated.”

What’s changed?

U.S.-China tensions

In 2004, the U.S. was focused on the Middle East, not the Indo-Pacific, and China was still far from being designated a “strategic competitor.” In 2004, Lula could maintain good relations with the U.S. at the same time as designating China an “ally” in the fight to reform the international order. “Nowadays,” says Santoro, “he will face much more pressure from the U.S.”

Celso Amorim, an important foreign policy figure in Lula’s inner circle, generated headlines back in January when he said that relations with China would improve under Lula. But Amorim’s most insistent message was that this improvement would not come at the expense of relations with Europe and the U.S.

A full tilt toward China is unlikely. “Lula is well known for being pragmatic,” says Igor Patrick, Research Fellow at the Wilson Center. “He would not throw away relations with the EU or U.S. to side with China.”

China’s a bigger beast

And it’s not just a question of yielding to outside pressure. As Thiago Bessimo, Institutional Director at Observa China, points out, “Lula wants a multipolar world order, but not necessarily with China at the helm.” Lula’s wariness of the United States is all about giving Brazil the room to chart an independent course. When Lula took office in 2003, he considered Brazil “a big country,” standing alongside China as an emerging power. Nowadays, Brazil and China are clearly in different leagues, and Lula will not want to reduce Brazil’s dependence on the U.S. just to become dependent on China.

On the campaign trail, Lula riffed on Bolsonaro’s 2018 rhetoric about China “buying” Brazil, warning that China is “occupying” Brazil. Lula was in electoral campaign mode, speaking at an industry confederation and saying something his audience wanted to hear, but it’s still surprising rhetoric from an old friend of China. Lula is unlikely to pursue protectionist policies at the expense of Brazil’s relationship with China, but his comments suggest that the Sino-Brazilian relationship won’t all be smooth sailing if he wins on Sunday.

Political and economic constraints at home

Regardless of the direction Lula chooses, he will not have the same bandwidth nor leeway as last time to pursue foreign policy objectives. The general elections on October 2 saw right-wing candidates make unexpected gains.

“Brazil is a different country 20 years later,” says Bessimo. “Bolsonarismo is not going away and Lula will also have a tough time in Congress.”

Facing opposition and division at home, Lula will not have the same luxury he enjoyed in the 2000s of pursuing foreign policy objectives. Neither will he have the same resources at his disposal. “The policy space is narrower now than when Brazil was surfing a commodity boom,” says professor Nogueira, referencing Brazil’s good economic fortune in the 2000s.

What to look out for if Lula wins

Given all this change, it is unclear how a friendlier stance on China might manifest in practice. Two things to watch out for are how Lula will approach BRICS and how he will approach China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

BRICS

Lula has already stated that BRICS will be at the forefront of his foreign policy. This activism will be welcomed by Beijing, which is pushing for an expansion of BRICS. There does, however, seem to be a question as to what extent Brazil will welcome this change. Lula’s politics suggest he’d be on board, but some Brazilian diplomats are concerned over the extent to which BRICS might be seen as an anti-Western grouping.

Whether or not Lula throws his weight behind expansion, his approach to BRICS would be a departure from the Bolsonaro era. Bolsonaro did not withdraw from BRICS, as some commentators expected, but he did cancel a parallel outreach program when Brazil hosted the BRICS summit in 2019. Bolsonaro’s anti-globalist instincts were tempered by hard economic truths soon after he was elected, but he never became a fan of multilateralism. If Bolsonaro does win re-election, BRICS is likely to remain far down Brazil’s list of foreign policy priorities.

The BRI

Another question is whether or not Brazil under Lula will finally join China’s Belt and Road Initiative. There are already plenty of Chinese infrastructure projects underway in Brazil, but it is one of only a handful of developing countries that have not yet signed a memorandum of understanding with Beijing on jointly building the BRI.

Bolsonaro resisted Beijing’s invitation for Brazil to join its “big family of the Belt and Road Initiative” when he visited China in 2019, but his predecessors in government didn’t sign up, either. Brazil is already the largest target of Chinese investment in Latin America, so it is unclear what Brazil would gain from providing its endorsement other than annoying the United States.

Given Lula’s enthusiasm for South-South cooperation, he could be the president that finally signs Brazil up to the BRI. Argentina signed on in February, and for its troubles received a package of agreements worth $23.7 billion. While some analysts, including Brazil-China Relations in the 21st Century author Maurício Santoro, believe that Lula will take Brazil into the BRI, others are uncertain. “I’m not sure if Brazil will be part of the BRI. Even with Lula, there’s no clear advantage, given we already have half of CN investments flowing toward South America,” says Tulio Cariello, research director of the China-Brazil Business Council.

The direction Lula takes on BRICS expansion and the BRI will indicate the extent to which Lula has adapted old pro-China policies to 2020s realities.

And the extent to which Lula’s old China policies can survive in the 2020s is questionable, but between Lula and Bolsonaro, Lula is the more China-friendly option. The China-Brazil relationship hasn’t been derailed by Bolsonaro’s Sinophobic tendencies, but neither has it flourished.