China’s revised law on women’s protection: What you need to know

The revised version of the Women's Rights and Interests Protection Law, voted for adoption by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee on Sunday and effective from January 1, is the first amendment to the women-focused legislation in 15 years.

Following two drafts and rounds of public consultation spanning nearly a year, China’s top legislative body has updated its decades-old laws on women’s rights, adding new provisions to better safeguard the interests of women in the workplace and society as a whole.

The revised version of the Women’s Rights and Interests Protection Law, voted for adoption by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee on Sunday and effective from January 1, is the first amendment to the women-focused legislation in 15 years.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

A draft of revisions was first presented to the public for feedback in December 2021 and received an unusually large number of comments. A second draft was released in April, which was also met with a great deal of enthusiasm from the public, demonstrating the public’s increased awareness of women’s well-being.

Initially passed in 1992 and previously modified twice, in 2005 and 2018, the law aims to guarantee women’s safety, honor their personal rights, and empower them. The latest revisions added 25 new articles to the previous 61, some of which were also updated.

According to Chinese state news agency Xinhua, the updated legislation will “strengthen the protection of the rights and interests of disadvantaged groups such as poor women, elderly women, and disabled women.” At a press conference last week, Zāng Tiěwěi 臧铁伟, the spokesperson for the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress legislative affairs commission, stressed that the revisions were based on “extensive research” and intended to solve “thorny issues” concerning women’s rights — namely, sexual harassment and discrimination in the workplace — adding that it’s impractical for Chinese lawmakers to “copy measures in the Western system.”

Jeremy Daum, a senior fellow of the Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center, told The China Project that although the new law shows “an awareness of the importance of women’s rights to society” and “a clear intention to protect women,” it still has room for improvement. One of its glaring weaknesses, he said, which has been on display in various versions of the law over the years, is how the legislation consistently addresses the rights of women in terms of the rights of men.

“The beginning of every section on various types of rights and interests always starts with the phrase women’s rights and properties should be equal to those of men. That’s a weird way of phrasing that,” he said. “It assumes that men are the norm and women are the other. They could have just said that all persons have equal rights in this regardless of sex.”

The revised law comes at a time when Chinese women are struggling to remain hopeful that a more equitable future is within their grasp after a series of scandals this year.

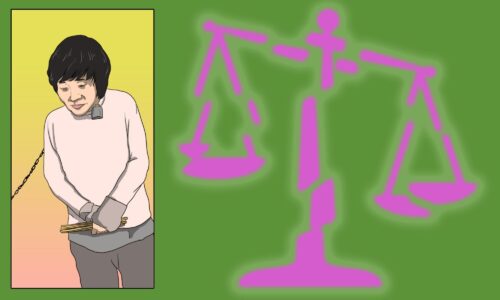

In January, grim footage of a Chinese mother of eight shackled by her neck and locked up in a freezing shed in Xuzhou sparked a provincial investigation and soul-searching national conversation about human trafficking and forced marriage in China. A few months later, a violent attack in the northeastern Chinese city of Tangshan, where a group of men were caught on camera assaulting a woman and her female friends at a barbecue restaurant, unleashed a renewed wave of anger and debate over male violence against women in the country.

Such news has put women’s issues at the forefront of Chinese people’s mind, which explains why “the amount of comments submitted during the public input period for the amendment was spectacularly high,” said Daum, who runs the China Law Translate project, a collaborative blog that has published a full translation of the revised law over the weekend.

“The amount of public attention to this law in general shows you how important it is, as well as how people were hoping for more,” he added. “This is a hot issue right now.”

Below are some highlights from the amendment, accompanied by commentary from Daum:

Media coverage of women’s issues

Before the official passing of the amendment, a newly added article about media coverage on women’s issues, which was revealed to the public by local news outlets, caused some strong reactions on social media. Placed under the section of “Rights and Interests in Person and Personality,” the paragraph in question stipulates that media reports involving women’s matters should be “objective and appropriate” and must not “infringe on the personality rights and interests of women through means such as exaggerating matters and excessive hype.”

Although the article is phrased in a way that suggests it’s in the interest of women, critics raised questions about whether the real intention was to deter journalists from writing about gender issues. Their worries, according to Daum, are not totally groundless.

“Given where it appears in the law, it seems to be about protecting women’s personality rights and making them not the subject of salacious media reporting,” Daum said. “But at the same time, there’s been a couple of stories related to women in the past year that received huge media attention and caused public opinion crises for the government, which in some cases felt the need to proactively address the problem. It’s natural for one to wonder if this article is about that. And we all know there’s media control in China. It’s strong.”

Daum suspected that “there’s a bit of both” in Article 28.

Sexual harassment

In order to increase female students’ awareness of sexual assault and sexual harassment, the updated law encourages schools to make sex education part of the curriculum and employ measures in areas such as management and facility. When it comes to the workplace, the amendment calls on companies to set up mechanisms to effectively prevent sexual harassment against women and promptly handle such complaints. However, legal ramifications for failing to do so are unclear.

“It’s a nice requirement for employers to have rules, but there’s no enforcement mechanism,” Daum said. “And the individual has no right to sue their employer for not having policies in place to address this.

“But beyond that, it’s not even clear when other mechanisms like the procuratorate would be available to get involved. The procuratorate is authorized to do public interest lawsuits for violations of women’s rights. But it sounds like that is waiting for problems to occur rather than enforcing a preventative mechanism of making employers have a policy. “

Daum noted that because Chinese laws are meant to be refined in practice by implementation rules and regulations, they are often written in a high level of abstraction, and it’s likely that better rules related to the amendment will come out later. But given the lack of provisions on employer responsibilities for prevention, even additional regulations introduced in the future won’t be able to fix the problem. “We might see some refinement and improvement on some of the laws that are there, but we won’t see totally new additions, most likely, at least not in a while,” he said.

Daum also pointed out that the final version of the law takes out some of the specific examples and definitions of what sexual harassment would be that were included in the proposed amendment. In the previous draft, there’s a list of five items clarifying that any comments with sexual connotations, inappropriate bodily behavior, sexually explicit images, or suggestions of benefits in exchange for sex toward a woman without her consent would constitute sexual harassment.

“It struck me as odd when I first noticed it. But as I looked more closely, I now think that they decided that this law is not the place to define that,” he said. “It’s not that they don’t think these things are sexual harassment. It’s a question of which law these should go in.”

In China, sexual harassment has long been a problem in both academic and professional settings. Due to a persistent culture of victim-blaming, Chinese women often feel reluctant to report harassment, and it is rare for such cases to make it to court in a legal system that places an unfair burden on survivors to prove that their allegations are true.

To further complicate matters, while the #MeToo movement has achieved many things in China since it took off in the country in 2018, including changing the public discourse around sexual assault and accountability, reshaping definitions of boundaries in the workplace, and transforming many industries such as entertainment and tech, it has been losing momentum in the past year due to suppression and censorship.

Gender and pregnancy discrimination at work

The amendment prohibits employers from asking female job applicants about their marital or parental situations and rejecting them based on their answers — a discriminatory practice that is repeatedly criticized by officials but still surprisingly common at workplaces in China. It also bans pregnancy tests as an item in physical examinations for employment.

The law states that female employees who already have jobs are protected from being fired or having their salaries slashed if they get married, become pregnant, or take maternity leave.

While on the surface such changes may seem to be rooted in the ideological principle of gender equality, the motivation for them could also be practical: China has been attempting to engineer a baby boom as its aging society grapples with record-low birth rates and marriage numbers. To make the idea of having children appealing to professional women, there’s an incentive for lawmakers to make sure having babies won’t be a career killer for them.