Jiang Zemin and the Naughty Aughties

The leader of China through its recent decades of breakneck economic growth died today. Many Chinese people and foreign observers are nostalgic for Jiang Zemin’s rule. But does the past just look better in contrast to the dourness and growing repression of the Xi Jinping era?

China’s former leader Jiang Zemin died today, November 30, 2022. For details, see our news story. The essay below was originally written as a chapter for the book The Chinese Communist Party: A Century in Ten Lives, edited by Timothy Cheek, Klaus Mühlhahn, and Hans van de Ven (© 2021, published by Cambridge University Press, and reproduced here with permission). It has been lightly edited, and photographs and video have been embedded in this version that do not appear in the original version. Please consult the print book for full footnotes.

Jiang Zemin and the Naughty Aughties

A parade in Beijing

On October 1, 2009, the Chinese Communist Party celebrated the 60th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic with an enormous military parade in Beijing. There were tanks, helicopters, planes, armored cars, amphibious vehicles, and thousands of soldiers from every major division of the People’s Liberation Army. State media proudly enumerated the numbers: 10,000 troops, 52 weapons systems, 151 warplane flyovers, and 12 intercontinental-range missiles. The parade also gave the world a glimpse of what was said to be the world’s first anti-ship ballistic missile (ASBM), the Dongfeng 21-C, nicknamed “aircraft carrier killer.”

The parade included what the New York Times called “improbably, a female militia unit toting submachine guns and attired in red miniskirts and white jackboots, and a fleet of floats with representations of a giant fish and Mount Everest.” Among the floats were four carrying outsized portraits of each of China’s postrevolutionary leaders, each decorated with two of the pictured leader’s trademark slogans:

Máo Zédōng 毛泽东

Long live Mao Zedong Thought

The Chinese people have stood upDèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平

Persevere with Deng Xiaoping Theory

Push forward with reform and opening up and the modernization of socialismJiāng Zémín 江泽民

Adhere to the important thoughts of the “Three Represents”

Comprehensively build a moderately prosperous societyHú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛

Implement the scientific outlook on development

Unswervingly follow the path of socialism with Chinese characteristics

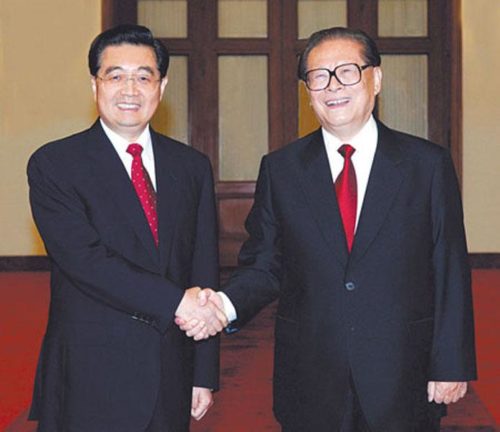

Two of the men depicted on the floats were still alive, and watching the parade: former president and General Secretary of the Communist Party Jiang Zemin, who stood behind the incumbent, Hu Jintao.

The last time Jiang had reviewed a military parade in Beijing — in 1999 for the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic — Deng had been dead two years, Jiang was leader of the Party, and no one was breathing over his shoulder. But for the next decade, Jiang would breathe over the shoulder of Hu Jintao, a president and Party general secretary who never really succeeded in marking out his own political turf. This meant that the first decade of the 21st century, the Naughty Aughties, when China went from third-page news to front-page story in the Wall Street Journal, was really the time of Jiang’s Communist Party.

What were the aims of the Communist Party from 2000 to 2010, under Hu, who was under Jiang? Was the Party at that time a reformist organization? Was Jiang a leader who could or did change the Party? Fundamentally, was the Party he left behind different from the Party of Deng? What did China’s increasingly globalized society make of this reformed Party?

Answers are difficult. China was a Wild West boomtown in the Naughties, an era of pregnant possibilities, with much craziness and vibrancy. The ghost of Jiang Zemin floated above it all. He continued to shape events through his proxies, the so-called Shanghai Gang or Shanghai Clique, a group of Jiang loyalists who had worked with the former leader when he ran the city of Shanghai as mayor and Party secretary from 1985 to 1989. Developments that he had set in train, or pushed along, or agreed to in the 1990s, such as China’s entry into the WTO, came to fruition in this decade.

I was living in Beijing at the time, working as an entrepreneur. My business was publishing a website (the now defunct Danwei.org) that covered Chinese media and politics critically. The Beijing city commercial authorities granted me a business license for technology consulting, which gave me legal cover to run a company that was producing uncensored media. Nobody ever checked up on what I was doing with my company. It felt like China was on the brink of a new era: I actually believed that I would be able to run an independent media company in Beijing, and the Communist Party would let me do it. The Party seemed open to new ideas: the Ministry of Culture even commissioned my company to arrange a forum attended by various foreign specialists in media and cultural fields to advise the ministry on how to engage with foreigners. Those were heady days. (My website was blocked in 2009, as the last of Jiang’s powers were waning.)

The era is too close to our own to allow for a steady bearing, but seen from today, in the first decade of the 21st century, the Party seems to have been making an uncertain but genuine attempt to withdraw its tentacles from society.

Ruling From Behind the Screen

Jiang had served as general secretary of the Communist Party of China from 1989 to 2002, chairman of the Party’s Central Military Commission from 1989 to 2004, and president from 1993 to 2003. But for most of that time, Deng Xiaoping had remained “paramount leader.” When Deng died in 1997, his People’s Daily obituary called him “One of the major leaders of the People’s Republic,” while the New York Times said that while he “formally retired from his last important post, chairman of China’s central military commission, in 1989 … he continued to wield immeasurable influence, reserving final say in all important political matters for several years afterward, and finally relinquishing power only as he grew frail and disoriented.”

Despite his frailty, Jiang’s hold over the Party remained questionable for the last few years of Deng’s life. “Veiled attacks on Jiang’s theories of governance” in Party magazines would “continue through 1997,” writes political scientist Bruce Gilley — a sign that powerful forces inside the Party were opposed to Jiang’s leadership. But by the end of 1997, Deng was truly gone, and Jiang was in charge. That year was “a landmark for Jiang Zemin,” according to Willy Wo-Lap Lam:

He presided over the historic July 1 Hong Kong handover. The Chinese economy grew by 8.8%while inflation dipped to 2%. The president shoved aside two long-standing enemies, Qiao Shi and Liu Huaqing at the 15th Chinese Communist Party Congress in September. A month later [he] achieved the long sought-after stature of world statesman by holding a historic summit with US President Bill Clinton at the White House.

But by that point, Jiang had only five years to go as official leader. The system of leadership transition set up by Deng that led to Jiang’s rule meant he was supposed to retire after two “terms,” or roughly a decade. Jiang stepped down as general secretary of the Party in November 2002 to make way for Hu Jintao. But the elder leader waited until September 2004 to relinquish his post as chairman of the Party’s Central Military Commission, and another six months to resign from his chairmanship of the state’s Central Military Commission. In other words, Jiang had formal power over the barrel of the gun until more than two years into Hu’s first term as leader. An equivalent would be an American president retaining the title of commander in chief of the armed forces more than two years after he had left the White House.

At a press conference in Hong Kong in 2000, Jiang Zemin lectured a critical Hong Kong journalist for being “too young” and “sometimes naïve.”

Jiang’s influence remained powerful even without a formal title: Six of nine new Politburo Standing Committee members appointed at the 16th Party Congress of 2002 were members of the “Shanghai Gang.” Three of Jiang’s men stayed on the Standing Committee after the 17th Party Congress in 2007.

So although Hu Jintao assumed all the trappings of China’s top leadership position when he took over as Party Secretary in 2002, he seemed almost chosen for his weakness and lack of revolutionary credentials. He was an uninspiring speaker, sometimes caricatured as a robot. He was the first leader of the People’s Republic without any direct ties to the Revolution. Although Jiang did not fight in the Civil War, he had been an underground student organizer in Shanghai, whereas Hu not only came from a merchant (capitalist!) family, he was just seven years old in 1949, and only joined the Party in 1964. He had never studied in the Soviet Union (or anywhere else outside China).

during the 16th Chinese Communist Party Congress in 2002, when Hu was elevated to Party leader and Jiang Zemin retired as General Secretary and President. REUTERS/Andrew Wong

BY

Hu Jintao and the “Most Democratic Body in the World”

Hu’s relative weakness was often said to demonstrate a strength of the Party’s method of collective leadership, by both Western commentators and Party leaders themselves. One of the Wikileaks Cablegate documents (dated July 2009) is illuminating:

Hu Jintao as Chairman of the Board?

Chinese Communist Party Politburo decision-making is similar to executive decision-making in a large company, two well-connected contacts say. Chen Jieren, nephew of Politburo Standing Committee (PBSC) Member He Guoqiang and editor of a Communist Youth League website, told PolOff [U.S. Embassy political officer] May 13 that Party General Secretary Hu Jintao could be compared to the Chairman of the Board or CEO of a big corporation.

[Wú Jiàxiáng 吴稼祥, who served under now-Premier Wēn Jiābǎo 温家宝 on the Central Committee General Office staff in the late 1980s, used the same analogy in a May 18 meeting with PolOffs. Wu said that PBSC decision making was akin to a corporation in which the greater the stock ownership the greater the voice in decisions. “Hu Jintao holds the most stock, so his views carry the greatest weight,” and so on down the hierarchy, but the PBSC did not formally vote, according to Wu. “It is a consensus system,” he maintained, “in which members can exercise veto power.”

Chen had told PolOff previously that he knew “on very good authority” that “major policies,” such as the country’s core policy on Taiwan or North Korea, had to be decided by the full 25-member Politburo. Other more specific matters, he said, were decided by the nine-member PBSC alone. Some issues were put to a formal vote, while others were merely discussed until a consensus was reached. Either way, Chen stated sarcastically, the Politburo was the “most democratic body in the world,” the only place in China where true democracy existed.

What Chen did not say is that outside observers had no way of knowing what was driving the decision making. If more than half of the Politburo members were under the influence of Jiang Zemin, the process was perhaps a little less democratic than Chen would have his interlocutor believe.

The Golden Age of Chinese Liberalism under Hu Jintao, and Jiang Zemin

Democratic or not, the first decade of the 21st century was a time of rapid change and economic opening up for Chinese society, which was accompanied by an influx of foreign technologies and ideas. At the same time, the government continued to remove itself from its citizens’ private and cultural lives. Civil society grew as activist lawyers, NGOs, university professors, and journalists pushed the boundaries of the politically possible.

The major events that defined China’s new reality in the 2000s happened under Jiang Zemnin’s leadership, before Hu Jintao became Party Secretary and president. First, in July of 2001, the International Olympic Committee selected Beijing as the venue for the summer games of 2008. Second, China became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in December 2001. This was negotiated by Jiang’s government, or, to be more specific, by his premier, Zhū Róngjī 朱镕基, who was much beloved by his Western counterparts and was one of the people who did most to convince Western business elites that China was in safe hands.

Jiang had laid the ideological groundwork for Communist China to join the WTO in the 1990s, with his “Three Represents” contribution to Party theory. This theory states that the Communist Party of China “should be representative of advanced social productive forces, advanced culture, and the interests of the overwhelming majority.” This was a welcome to “entrepreneurs” (what the ideologically unenlightened might call capitalists) as representatives of “advanced social productive forces” to join the Party, a reassurance to China’s educated elite (as “forces of advanced culture”) that the Party respected and valued their knowledge, and a promise to Chinese society that the Party would take a backseat. Making money and having fun was okay as long as one did not challenge the Party’s right to rule.

While it is often mocked for its ridiculous-sounding name, the theory was actually translated into practice — essentially, that the Party should welcome businesspeople into its fold, and be more responsive to citizens who are not Party members, including respect for China’s educated elites. The policy led to important changes: Almost every significant Chinese entrepreneur is now co-opted into the Chinese government as an adviser to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), and Chinese tycoons sometimes join the entourage of presidential visits, as their Western counterparts do. This was a remarkable change for a party that still called itself Communist: the country’s biggest capitalists were (and continue to be) not only welcomed, but also celebrated by state media and propaganda organizations. Likewise, a fair number of China’s intellectuals found work and rewards working in the Party, for the Party’s goals, or by aligning their public voices to avoid open contradiction with Party rule. While dissidents remained, China’s establishment intellectuals, now pocketing a nice salary (or two), found ways to couch their political criticism as advice to the Party. At universities and a growing number of think tanks, intellectuals found productive, prestigious, and well-paid work as teachers in classrooms and as researchers.

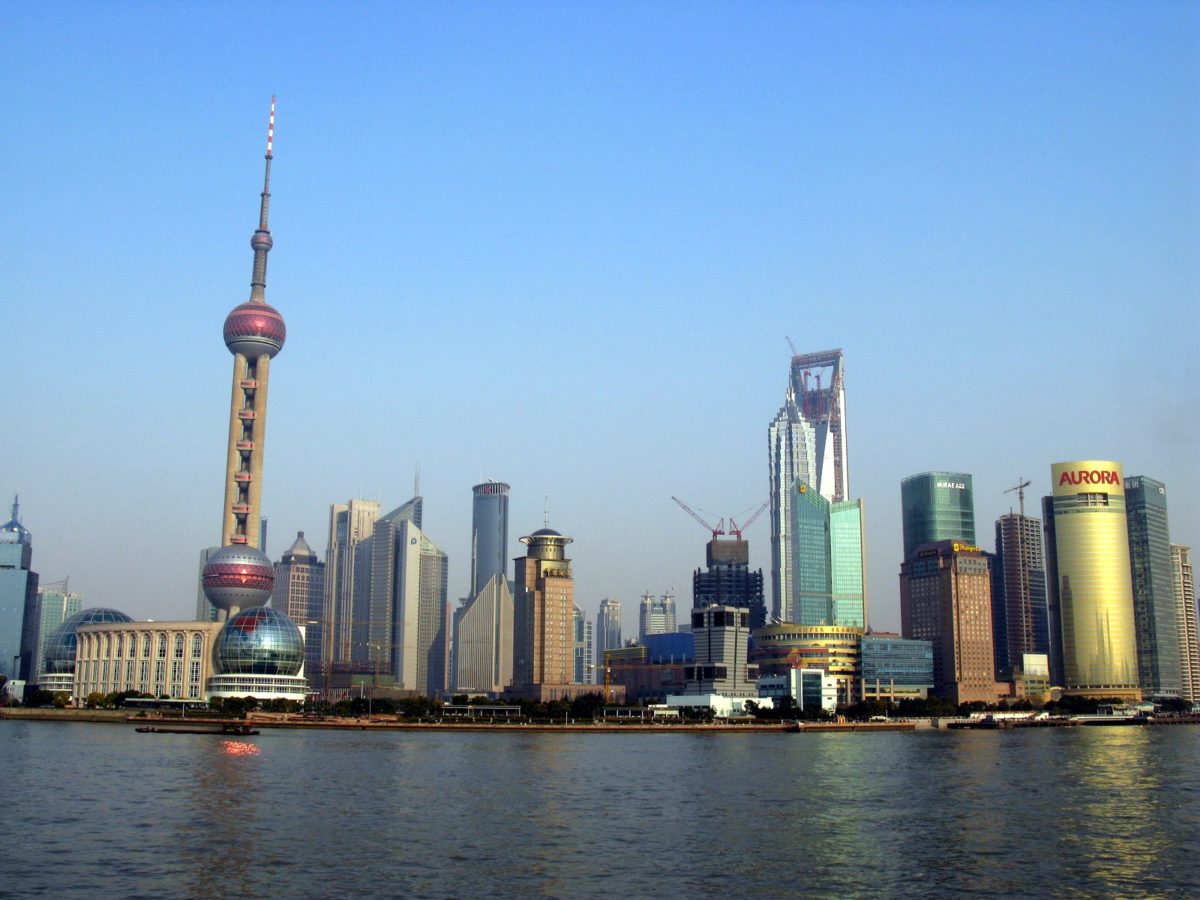

Fears that China would turn back on economic reform after the death of Deng Xiaoping in 1997 were thoroughly dispelled by the reformed Party under Jiang’s leadership. In fact, Jiang oversaw a period of extraordinary growth, an economic boom of a scale the world had never seen.

With WTO membership, China’s status changed, very suddenly. No longer was the country a poor developing nation that Wall Street bankers and international political leaders could afford to ignore. Now it was a market of 1.4 billion people that made every multinational-company executive salivate, and go on to lose a mint. Now it was preparing to host the most ambitious Olympic Games ever, a “coming-out party” on the world stage.

In the first decade of the 21st century, China became the world’s second-largest economy and the world’s largest goods exporter. The country experienced the fastest growth in GDP per capita of any major economy in human history — in 2001 China’s GDP was $1.3 trillion. By 2010, it was $6.1 trillion. Average GDP growth was around 10%for a whole decade. Foreign direct investment (FDI) in China leapt from under $1 billion in the year 2000 to more than $100 billion in 2010. Companies and entrepreneurs from all over the globe arrived in China, seduced by the promise of a gargantuan market and a government that seemed to encourage any kind of business activity, as long as it helped grow China’s economy. Even Google — which at the time still promoted its old corporate slogan “Don’t do evil” — set up shop in China in 2006, promising to expand the range of information available to Chinese internet users (they beat a hasty retreat in 2010).

Although foreign companies tended to get more anglophone press, Chinese companies, both private and state-owned, were perhaps even greater beneficiaries of China’s entry to the WTO and the positive buzz that the coming Olympic Games generated. Nowhere was this more obvious than in the internet industry. Companies like Alibaba, Baidu, Sina, and Tencent began life as clones of Western tech services in the late 1990s, but by 2010 they had established themselves as major global players with user numbers matching and exceeding their American peers like Google and Facebook. The framework that the Party provided these companies under Jiang Zemin’s leadership provided some, but not all, of the conditions for this growth. China blocked outside Internet companies effectively with what scholars Geremie Barmé and Sang Ye dubbed “The Great Firewall of China.” Thus, the Chinese companies did not have to compete for the China market with Facebook and later Twitter and Google. Outside tech, Chinese companies also began competing globally: from shipbuilding to real estate, chain restaurants to fashion brands — China stepped up its capitalist game at an awesome speed under the rule of Hu Jintao, and the man standing behind him at the military parade in 2009, Jiang Zemin.

With the flows of money came people: a population census conducted in 2010 found more than a million foreign citizens residing legally in China, including citizens of Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan, but not including short-term visitors and businesspeople living in China without a long-term work visa. In the previous census of the year 2000, foreign citizens were not even counted. The foreigners brought capital, and intellectual property, but they also brought ideas. Deng Xiaoping is supposed to have said, “If you open the window for fresh air, you have to expect some flies to blow in,” meaning that opening China’s market to the world meant a certain acceptance of values and ideologies that were anathema to the Party. The flies swarmed in.

U.S. TV host Mike Wallace conducted a candid interview with Jiang in September 2000 in New York.

During the 2000s, foreign and domestic money poured into the internet, opening up channels of direct communication between citizens, and enabling small provincial newspapers to get nationwide exposure for reporting. This had consequences for the Party, especially in local governance. For example, in 2003, the Southern Weekly, a Guangzhou-based newspaper, published an investigative report about a migrant named Sūn Zhìgāng 孙志刚. Sun was arrested in Guangzhou for not having a “residence permit,” and was beaten to death while in police custody in Guangzhou. The article went viral among China’s then 80 million-strong population of internet users. By June that year, the government abolished the “custody and repatriation” policy established in 1982 that led to Sun’s detention.

That same year, a young journalist with the online name “Mùzi Měi” (木子美) started a blog in which she recorded her sexual experiences. After publishing a rather negative “review” of her experiences with a well-known rock musician, her diary became an overnight internet hit, read by millions of Chinese youngsters. Blogging became a household word as millions of ordinary citizens — and professional journalists — discovered the joy of publishing without an editor or censor. In December that year, Menbox, China’s first openly gay glossy magazine, began distributing to newsstands in Beijing, Shanghai, and other large cities. The magazine was produced in partnership with the prestigious Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

In 2004, the advertising operations of the state-owned Beijing Youth Daily Newspaper Group were listed on Hong Kong’s stock market — the first such listing of a mainland media company. As government departments ceased subsidies to local and some national newspapers, these publications were forced to go to the market for money, and the market rewarded interesting news above propaganda. For the first time in the history of the People’s Republic, there was a powerful commercial force encouraging journalists and editors to take risks.

Some of these challenging social developments came through entertainment. In 2005, provincial television station Hunan TV’s reality talent show Super Girls (超级女声) broadcast the final, knockout competition. The finalists were far from conventionally feminine, nor did they fit any model of youth or womanhood that the Party would endorse. But the show was a nationwide hit, drawing advertisers away from the stodgier programs on China Central TV (CCTV) and giving viewers a tiny taste of democracy: winners were decided by vote via mobile phone text message. Some 8 million people “voted” on the final night of the show. In 2006, the Rolling Stones played a concert in Shanghai. Also that year, the Uyghur economist Ilham Tohti founded a website called Uyghur Online, which published critical commentary in Chinese and Uyghur on social issues. (In 2014, Tohti was found guilty of “separatism,” and sentenced to life imprisonment.) The Party had given an inch in the “Three Represents,” but society tried to take a mile.

In fact, as the 2008 Olympic Games approached, the Party advertised its openness to the world and allowed an unprecedented amount of unsupervised intellectual and cultural activity. In retrospect, some commenters called it the “golden age of Chinese liberalism under Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao.” But perhaps it should be the “golden age of Chinese liberalism under Jiang Zemin,” because the elder leader’s presence was undeniable, both physically and ideologically.

Jiang appeared in public on multiple occasions during every single year of Hu Jintao’s tenure, often accompanied by senior leaders still in office. Jiang loyalists and relatives remained in key positions in the Party bureaucracy. They also commanded power in the growing economy of state assets under private or semiprivate control. But more importantly, his “Three Represents” — which was included in amendments to the Party and state constitutions at the 16th Party Congress in 2002 — set the tone for the next decade.

By contrast, Hu Jintao’s contribution to Party theory, the “Scientific Outlook on Development,” was a veritable nonevent. Party propagandists struggled to define this as anything more than reheated leftovers of “socialism with Chinese characteristics” (Deng’s policy from the 1980s).

It got worse. The other slogan associated with Hu is the schoolmarmish “Eight Honors, Eight Shames,” which he began promoting in 2006 as a moral code for all Chinese, but especially Communist Party cadres:

Honor to those who love the motherland, and shame on those who harm the motherland.

Honor to those who serve the people, and shame on those who betray the people.

Honor to those who quest for science, and shame on those who refuse to be educated.

Honor to those who are hardworking, and shame on those who indulge in comfort and hate work.

Honor to those who help each other, and shame on those who seek gain at the expense of others.

Honor to those who are trustworthy, and shame on those who trade integrity for profits.

Honor to those who abide by law and discipline, and shame on those who break laws and discipline.

Honor to those who uphold plain living and hard struggle, and shame on those who wallow in extravagance and pleasures.

Communist guided Party members on self-cultivation, and subordinating personal interest to the greater — that is, the Party’s — good Lei Feng embodied selfless devotion to the collective and Mao Zedong Thought in the 1960s. But unlike Liu’s text, Hu’s moral code was not written for a revolutionary party: the context was a growing sense among the public — reflected in the Chinese media and internet commentary — that China’s rapid economic development had left the country in a spiritual vacuum: the old ideologies and Communist values had disappeared, replaced only with rampant materialism, corruption, and moral decadence. Lei Feng had been revived, but the Communist boy scout was laughed off as a meme for stupidity. The emptiness of the “Scientific Outlook on Development” did not succeed in rallying the Party and country around a set of values, but the Eight Honors, Eight Shames had even less impact. Even worse for Hu Jintao’s legacy, by 2006, China’s Internet population was heading for 200 million, and a number of those people were writing blogs that ruthlessly mocked Hu’s campaign.

The Olympic Games and the Global Financial Crisis

Despite growing public cynicism about the Party’s confused ideological messaging, for most citizens, the extraordinary economic growth of the post-WTO years and its concomitant rise in living standards were more than enough to compensate. The Olympic Games became a promise and then an achievement of the Party that resonated with large numbers of Chinese people who were genuinely proud of the country’s apparent arrival on the world stage. Not even riots in Tibet in March 2008, nor the Wenchuan earthquake in Sichuan in May that year that killed around 70,000 people, dented public enthusiasm for the Olympics, and for China’s new image as a major global player. In fact, together with the games, those two events helped solidify a sense in China that the country had finally stood up.

A new generation of internet-savvy young Chinese people who understood English were horrified by the way their country was represented in Western media coverage of the protests and subsequent ethnic conflicts in Tibet, which tended to be sympathetic to the Tibetans. This trend was epitomized by the website Anti-CNN.com, founded by a student in Beijing named Rao Jin, dedicated to exposing the alleged hypocrisies of the Western press. (Disillusionment with Western ideas and Western media was not novel: The 1996 best-selling China Can Say No (中国可以说不) by former Americophiles Sòng Qiáng and 宋强 and 张藏藏 Zhāng Cángcáng expressed similar attitudes.) These were informed and independent critics, not just Party stooges. These young intellectuals “jumped the firewall” (accessing Western media by using VPN software). The Party may have become more irrelevant for many Chinese youth, but ardent patriotism (that tends to buttress Party legitimacy) had taken root and took issue with slanted Western portrayals of China. Anti-CNN was just the latest example of young Chinese people defending the PRC and its government without direct coercion from the Communist Party, something that continues to be underemphasized in media reports about young Chinese nationalists.

The Party even managed to turn the Wenchuan earthquake into a propaganda success. In the first few weeks after the quake, journalists and bloggers had exposed deadly local government malfeasance, such as schools built with substandard materials, so local officials could skim money off the top, which collapsed during the quake, killing thousands of students. But the government soon silenced such reporting, and dispatched Premier Wen Jiabao to the epicenter of the quake to pose for photos, and assure the people that the central government had their back. (A similar dynamic would play out in early 2020 as Beijing turned the narrative about the COVID-19 epidemic from one of government cover-ups and bungling to a story of disease-fighting success and global leadership.)

By the time the Olympic Games opening ceremony began at the auspicious date and time of 8 p.m. Beijing time, August 8, 2008, the Communist Party had succeeded in convincing much of the Chinese population into celebrating. The event comprised a mass concert of dance, music, and lighting involving thousands of performers at the Beijing National Stadium, also known as the Bird’s Nest. The show was produced by film director Zhāng Yìmóu 张艺谋, with fireworks by visual artist Cài Guóqiáng 蔡国强. Both artists were once considered avant-garde in China (and beloved by the international art scene), but now the two men had found comfortable positions producing light shows for the party-state. Jiang’s “Three Represents” at work.

And what a show it was. It wowed the audience in Beijing. Television viewers across the world were suddenly exposed to a China that looked rich, modern, and powerful. China’s “Prosperous Age” was at hand. The rest of the games did not disappoint: China ran a smooth operation, the country looked good on global television, and China raked in the lion’s share of gold medals, 48 compared with America’s 36 and Russia’s 24.

Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao both attended the opening ceremony of the games. They must have been very happy with that evening’s performance, and with the rest of the games, which were incident-free and competently managed. They would soon have cause to be even happier.

The games ended on August 24. Less than a month later, on September 15, 2008, the investment bank Lehman Brothers collapsed, heralding the global financial crisis of 2008. Within a year, the economic contagion had put much of the globe into recession, but China was partly insulated because its economy was not completely interconnected with world financial markets. And the Chinese government kept the country’s economy steaming along with enormous stimulus packages. China came out on top.

This had consequences. The Olympic success, combined with Western financial woes, convinced many that China’s day had come. Deng Xiaoping had advised “hiding our strength and biding our time.” No more. By 2010, the scholar David Shambaugh — not a China hawk by any means — was writing about Beijing “showing its claws,” and many other observers began to observe a new swagger in the manner of senior Party officials. If Beijing was showing its claws abroad, at home it was also baring its fangs. Although the Chinese economy emerged from the financial crisis unscathed, the Party had plenty to worry about: perhaps most importantly, a deadly ethnic riot in Xinjiang in August of 2009, and fears about an increasingly critical — and exponentially growing — social media commentariat. Events abroad were worrying: Iran was experiencing its “Facebook revolution,” cheered on by techno-utopians and much of the Western press.

In response to these threats, the Leninist machinery of the party-state began to reassert itself. Domestic internet censorship intensified. Veteran dissident and literary critic Liu Xiaobo, who had headlined an effort by a number of Chinese intellectuals to push for democratic reforms in Charter ’08 as an internet open letter, was peremptorily arrested for the effrontery. He would be convicted and died still under incarceration in 2017. Preparations for the 60th anniversary military parade in Beijing attended by Jiang and Hu involved chasing further dissidents and other troublemakers out of Beijing. By the end of 2009, all major foreign social media websites had been blocked. Rights activists, lawyers, journalists, and bloggers saw the end of the golden age of liberalism under Hu Jintao (and Jiang Zemin), and even in business the talk was less about the private sector and more about “the state advancing and the private sector retreating.” The Party began to take back that “mile” from society.

The Ten Grave Problems of the Hu–Wen Era

In the closing years of the Hu Jintao administration, the Party had even more to worry about. There was a popular perception that corruption was out of control. Citizens and senior officials alike could hear the environmental destruction wrought by decades of breakneck economic growth in the coughs of their children. Extreme inequality was obvious in Chinese cities where Bentleys competed for road space with bicycle couriers earning a couple of hundred dollars a month. In 2011, a high-speed train crash near the city of Wenzhou that killed 40 people prompted even the Communist Party mouthpiece the People’s Daily to wonder in an editorial whether China had not lost its way pursuing a “blood-soaked GDP.” Stories of corruption abounded. The Chinese internet lit up in March 2012 after reports that top Hu Jintao adviser Ling Jihua’s son died in a car crash in Beijing — in a Ferrari, accompanied by two half-naked women. Also, that year, the New York Times and Bloomberg published separate stories detailing the wealth accumulated by close family members and relatives of both incumbent premier Wen Jiabao and president-to-be Xi Jinping.

By the end of the naughty aughties, messaging in state media and scuttlebutt from diplomats reported in the media had already begun to make it clear that the Communist Party machinery was settling on a choice of successor for Hu Jintao. It was Xi Jinping, the son of one of the “Eight Immortals” of the Chinese revolution, Xí Zhòngxūn 习仲勋. Xi did in fact assume leadership of the Party and the country. The era of Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao came to a formal end on November 15, 2012, when Xi Jinping was appointed general secretary of the Communist Party and chairman of the CPC Central Military Commission by the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. His rise was not a sure thing: Bó Xīlái 薄熙来, another son of a revolutionary leader, was widely seen as a powerful rival to Xi, but his career came to a dramatic end after his wife was found guilty of murdering a British businessman in 2012. Bo himself ended up behind bars on corruption charges, leaving Xi untouchable.

Both Jiang and Hu attended the meeting when Xi’s ascent was formalized. It was not, perhaps, as happy an occasion as the sixtieth anniversary military parade for them three years earlier. This time they watched from the sidelines: there was a new man in charge. However, many observers, both inside and outside China, looked forward to Xi taking power as Party secretary and president. The New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof predicted that Xi would “spearhead a resurgence of economic reform, and probably some political easing as well.” Kristof bravely, or naively, went on to forecast that “Mao’s body will be hauled out of Tiananmen Square on his watch, and Liú Xiǎobō 刘晓波, the Nobel Peace Prize–winning writer, will be released from prison.” (Needless to say, Liu Xiaobo died in prison in 2017 and Mao Zedong’s corpse is still in the mausoleum at Tiananmen Square.)

Even commentators who did not see Xi as a reformer recognized that he had inherited a government that was struggling to cope with the result of its successes. In 2007, Wen Jiabao himself had warned of the “Four Uns” — that the Chinese economy had become “unbalanced, unstable, unco-ordinated, and unsustainable.” In August 2012 — a few months before Xi was anointed top leader — Dèng Yùwén 邓聿文, a senior editor at the Party School journal Study Times, published an editorial titled “Ten grave problems left behind by the Hu–Wen administration.” The ten problems were:

1. No breakthroughs in economic restructuring and constructing a consumer-driven economy

2. Failure to nurture and grow a middle class

3. An increased rural–urban gap

4. Population policy lagging behind reality

5. Bureaucratization and profit-incentivization of educational and scientific research

6. Environmental pollution continuing to worsen

7. Government failure to establish a stable energy supply system

8. Moral lapses and the collapse of ideology

9. “Firefighting” and “stability-maintenance” -style diplomacy, lacking vision, strategic thinking, and specific measures

10. Insufficient efforts to push political reform and promote democracy

Xi had his work cut out for him.

Toad Worship in Xi Jinping’s New Era

Jiang’s network of loyalists in the Party leadership were almost completely removed by the 18th Central Committee that selected Xi as Party secretary and president in 2012. Within months, Xi began a crackdown on corruption (and his political enemies), civil society organizations, and the media. Xi strengthened governing techniques invented during Jiang’s rule: the crackdown on Falun Gong since 1999 became a template for religious repression in Tibet and, under Xi, in Xinjiang. The Great Firewall was invented in the 1990s; Xi fortified it and promoted it as a positive feature of internet sovereignty.

However, it would take a few years for Xi’s autocratic tendencies to be widely acknowledged. In 2013, it was not yet obvious that Xi’s China would be a much more repressive place. State media and official reports from Party meetings frequently quoted Xi on the need for reform, and observers read what they wanted into that word. Nicholas Kristof was only one of many believers in the liberal possibilities of Xi’s rule.

That year, Dutch artist Florentijn Hofman inflated an enormous yellow duck and tethered it near the waterfront of Hong Kong island. The installation immediately inspired copies in cities across China, initially all yellow ducks, but later a whole menagerie of floating animals. By 2015, there was a giant inflatable toad floating on Kunming Lake at the Summer Palace in Beijing. Photographs of the toad circulated on the internet and online wags soon began comparing the toad’s expression to former president and general secretary of the Communist Party Jiang Zemin — the resemblance lay in his thick black spectacles and pants pulled up way past his waist.

Despite the mockery inherent in comparing an elderly Party leader to an inflatable toad, an online fan culture dedicated to Jiang began to develop called “toad worship culture” (蛤蟆文化). Adherents, who called themselves “toad fans,” created online groups to share videos, photos, memes, and quotes of Jiang. By 2015, it was also apparent that Jiang’s China had been a much more tolerant place than the country ruled by Xi Jinping. Part of the appeal of toad culture seemed to be nostalgia for a time when China’s leader was more approachable, given to off-the-cuff remarks to journalists in several languages, and playing the erhu or piano in front of foreign dignitaries and television cameras. And nostalgia for a time when it seemed that Chinese civil society and freedom of expression were expanding.

Compared to Xi Jinping’s grim efficiency, Jiang appeared in a whole new light to young Chinese internet users, who might not even have been born when the Elder (长者) — as some toad fans called Jiang — was in office. Was he a more enlightened ruler than Xi? How much responsibility does Jiang bear for the illiberal nature of the Chinese Communist Party under Xi Jinping?

In a caustic essay criticizing Xi for his handling of the COVID-19 outbreak, the legal scholar Xǔ Zhāngrùn 许章润 — whose recent writings have earned him suspension from his teaching duties at Tsinghua University and house arrest — had this to say:

The Three Represents and the ideas [and policy changes of the time] represented a relative apogee of possibility; since then there has been an evident downward curve which, in recent years, has indicated that the Communists are ever more obsessed with control over their Rivers and Mountains, in particular by means of big data totalitarianism.

Toad culture is nostalgia for that “apogee of possibility,” but is the toad himself worthy? Perhaps not. The Three Represents may have been a sincere attempt to democratize the Party, or at least give it a mechanism to hear public feedback and allow citizens to participate in the political process a little more than previously. But when he left office, Jiang left in place a caretaker administration that was never powerful enough to make any real changes. Hu and Wen, with Jiang watching from behind, just kicked the can down the road when it came to so many urgent problems facing China, from inequality to environmental degradation to deteriorating relations with ethnic minorities. Writing in 2015, Chinese journalist Shi Feike commented on toad culture with a judgment that may ring true when the Party eventually leaves the stage:

The nostalgia wave for the “toad’’ is a natural outcome of the comparison with the “bun” [a derogatory nickname for Xi Jinping]. But actually, there is nothing to be nostalgic about.

The trend in the past three decades has always been that each leader is less accomplished than his predecessor.

★★★★★

This essay was originally written as a chapter for the book The Chinese Communist Party: A Century in Ten Lives, edited by Timothy Cheek, Klaus Mühlhahn, and Hans van de Ven (© 2021, published by Cambridge University Press, and reproduced here with permission).

It has been lightly edited, and photographs and video have been embedded in this version that do not appear in the original version. Please consult the print book for full footnotes.