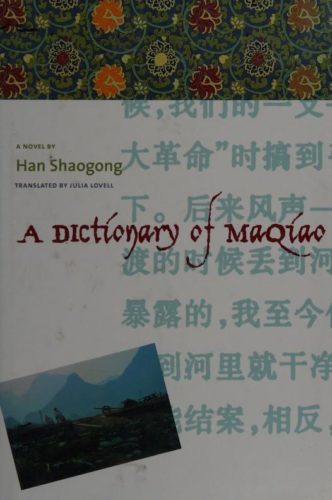

This is book No. 5 in Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

“Han’s novel is an eccentric handbook on a village in rural China during Mao’s Cultural Revolution.”

—The North Carolina News and Observer

“The Dictionary of Maqiao is innovative, interrogating the local to capture the universal.”

—The Newman Prize Committee

“The translation, by Julia Lovell, brings us as close as possible to an appreciation of the novel’s original style and its multi-layered meanings…the peasant vocabulary — vulgar, quaint, superstitious — which so perplexes the young outsider is also revealed to be cunningly subversive, an antidote to the totalitarian imposition of a ‘reality’ irreconcilably at odds with the real thing.”

—The Boston Globe

“A rich gallery of precisely sketched characters including the truculent beggar ‘king’ and malcontent Old Master Nine Pockets; Teixang, the recklessly unfaithful wife of an ineffectual Party leader; Ma Wenjie, lord of a feared ‘bandit army’; and versatile artist Yanwu, whose paintings are declared ‘reactionary’ for failing to create convincing likenesses of Chairman Mao. The result is a subtle and smashingly effective critique of the futility of totalitarian efforts to suppress language and thought — and, more to the point, a stunningly imaginative and absorbing work of fiction.”

—Kirkus

About the author:

Hunan-born Hán Shàogōng 韩少功 (born 1953) was labeled an “educated youth” and sent down to the countryside in the Cultural Revolution. In the 1970s his early fiction criticized the excess of the Maoist era. Initially, Han employed modernist techniques in his writing, but in the 1980s emerged as a major voice in the Xungen (or “search for roots”) Movement that distanced itself from the Maoist idea of a hegemonic Chinese culture and sought out the local and the pluralistic. Other members of the movement include Mò Yán 莫言 and Jiǎ Píngwá 贾平娃. In 1987 Han published a translation of Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being. A Dictionary of Maqiao is certainly Han’s best-known work, both within China and internationally, though he has subsequently written half a dozen other novels. In 2011 Han was awarded the prestigious Newman Prize for Chinese Literature.

The book in 150 words:

A Dictionary of Maqiao (translated into English by Julia Lovell) is a novel set in the remote and isolated Hunan village of Maqiao. It purports to be a collection of 115 articles, or vignettes, on Maqiao life and manners written by a young student sent there as part of the “Down to the Countryside Movement” in the 1960s. The articles take the form of a “dictionary” of the uniqueness, or quirkiness, of Maqiao life and linguistic oddities — the word for “beginning” is the same as the word for “end”; “little big brother” means older sister; to be “scientific” means to be lazy; and “streetsickness” is a disease afflicting villagers when they visit towns and have to avoid other pedestrians. It is at one and the same time amusing and witty while also being a dissection of the ridiculousness of the Cultural Revolution.

Your free takeaways:

“In Hunan, contradictions are not contradictions. They’re normal. Life here is a bit like Chinese food. Throw lots of different things into a wok and stir them around.”

“Maqiao people have a very simple way of expressing flavors. Normally, one umbrella term suffices for anything that tastes good: ‘sweet.’ Sugar is ‘sweet,’ fish and meat are also ‘sweet,’ boiled rice, chili pepper, bitter gourds are all ‘sweet.’ Outsiders have found this hard to understand: was it because their sense of taste was crude, and therefore they lacked vocabulary to describe flavors? Or was it the other way around: had a lack of vocabulary to describe flavors caused their palate to lose the ability to differentiate?”

“Although standard Mandarin has words like ‘seasick,’ ‘carsick,’ and ‘airsick,’ it doesn’t have Maqiao’s ‘streetsick.’ Streetsickness was an illness with symptoms similar to seasickness, but which struck sufferers instead on city streets, causing greenness of face, blurred eyesight and hearing, loss of appetite, insomnia, absent-mindedness, apathy, weakness, shortness of breath, fever, irregular pulse, sickness and diarrhea, and so on; female sufferers would tend to get irregular periods and run out of breast milk after giving birth. A whole swathe of quacks in Maqiao had special prescriptions for curing streetsickness, including wolfberry, tuber of gastridia, walnuts, and all manner of things.”

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

Han Shaogong was looking back a quarter-century to the Cultural Revolution, a time he knew as a young man, “a sent down youth.” But his A Dictionary of Maqiao was published at a time when concerns around rural matters were largely off the agenda. The Jiāng Zémín 江泽民 era was still in full swing — the emphasis on export-led growth, urbanization (by now up to around 36 percent of the population and still rising), and luring inward investment while pump priming through massive construction projects. Simply put, the economic boom of the 1990s had made little to no impact on the rural economy and the tens of thousands of country villages. The peasantry, as our previous bookshelf entrant Graham Peck might have noticed, remained under-educated, over-taxed, and shut out of urban lifestyles, better healthcare, and the general boom of living standards in coastal cities. Raising rural incomes was seen as a paramount task, and relieving the burden on the peasantry a necessary thing. It was to be, at least in their vocalizations, a key task of the incumbent Hú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛 – Wēn Jiābǎo 温家宝 administration. It wasn’t just about improving lives though; it was about the long-term survival of the Communist Party too.

Han’s Dictionary was taken by readers to be a paean to rural life — folkloric stereotypes of cuckolded husbands, long-suffering wives. At times there is something of Chaucer about life in Maqiao. Yet it was also a call to accept what Han saw as the impossibility of universalizing, or normalizing, language. Many of the “entries” in Dictionary draw attention to the confusion, comedy, and calamitousness of trying to enforce a common language with common meanings on a massive body of people.

Han also draws on a much wider variety of sources and influences than most post-1949 Chinese authors — Confucius and Laozi, but also Freud. Ultimately, Han Shaogong’s argument is that parochialism can be universal, as it also deals with the fundamentals of human life and society. China rural dwellers are not as often described as the “black ants,” the unseen, but are indeed fully formed 3-D human beings, and Maqiao’s inhabitants are characters as rich and colourful as Dickens’s Londoners, Hugo’s Parisians or Babel’s Odessans.

Han humanizes the peasantry, the Chinese countryside in all its oddity and humor. He elicits sympathy for the peasants at a time when they were being sidelined while being held up on a pedestal by political leaders, both historically in the Cultural Revolution and by the Jiang Zemin leadership who claimed growth in their name but channeled any fruits of that growth to the urban areas. Han Shaogong’s A Dictionary of Maqiao was a call from the Hunan countryside — we’re here, we survive, and we’re not going anywhere.

Next:

Han Shaogong sought to parody village life and expose the ridiculousness of the Cultural Revolution in A Dictionary of Maqiao. But how much had the stresses and strains of rural life, the endemic poverty, and the perceived injustices and corruptions of Chinese rural life changed over 30 years after Han’s recreation of his experiences in Hunan in the 1970s? In the first years of the 21st century, supposedly China’s century, a husband-and-wife investigative reporting team set out to answer exactly that question. And their answers provoked a storm.

Check out the other titles on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.