The relocated couriers who risked their health in COVID-ravaged Beijing

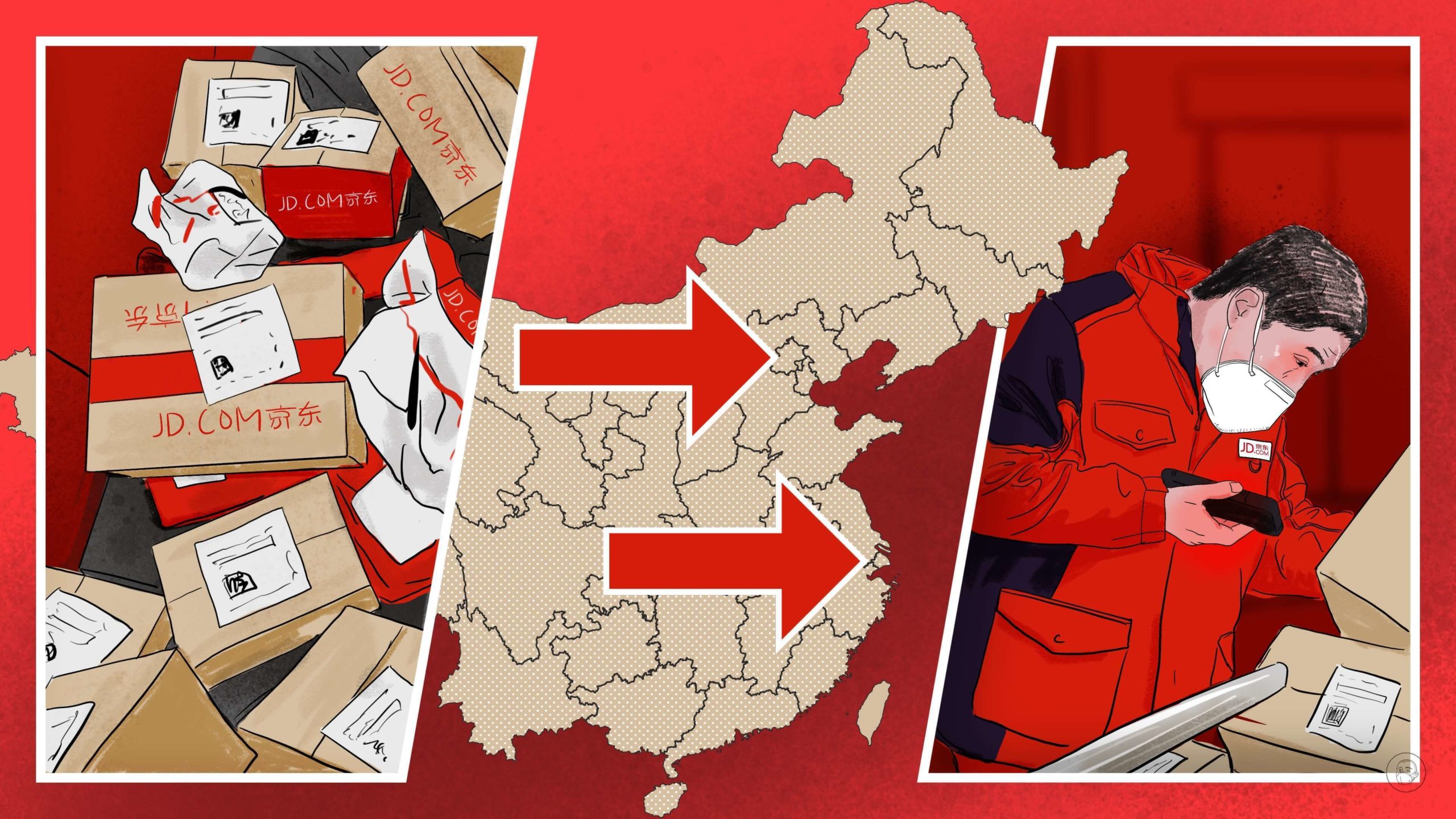

When a rapid spread of COVID-19 engulfed Beijing and caused severe delays in package delivery, an army of couriers from other cities were relocated to alleviate the problem. Their bravery has led to a national conversation about privilege and the role of essential workers.

Over the recent Spring Festival holiday, 330 million packages were delivered across China, an increase of 10% year-on-year, according to data released by the State Post Bureau. For people in Beijing, these numbers would have been unfathomable about two months ago, when sorting facilities were overloaded with packages and delivery capacities were stretched to the limit due to a COVID-induced labor shortage.

What it took to turn the situation around was a government directive, carried out by thousands of migrant workers who agreed to be relocated to the capital, where they risked their health to keep the city’s logistics operation running.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

Some of the relocated couriers chronicled their weekslong grind and exhaustion on Chinese social media. One of them is a man from the southwestern province of Yunnan, who posts on Douyin — the Chinese version of TikTok — under the name “Deliverymen support Beijing” (快递小哥支援北京 kuàidì xiǎogē zhīyuán běijīng). In a video from mid-December, the man told his followers: “When I decided to come to Beijing, I was prepared mentally to get infected with COVID. I have been here for three days.

“I hope I can get COVID soon. If I get COVID, I can have antibodies. Then I don’t need to worry anymore. The mental torture is worse than the physical torture. I deliver packages for COVID patients every day. Many people around me tested positive. To be honest, I am a little afraid.”

He didn’t disclose his name in the clip, but when he showed a bag of supplies provided by his employer, his name on the bag read Xiè Huálóng 谢华龙.

Toward the end of November in 2022, China seemingly lifted its pandemic restrictions overnight. The number of COVID-19 cases in Beijing spiked in the following weeks. As more and more local couriers contracted the virus and became unable to work, the delivery system in Beijing suffered devastating disruptions.

A deliveryman surnamed Jia told The China Project on December 20, “Delivery work requires physical strength, and people cannot do it when they are sick. With the Spring Festival approaching, many want to return home, resulting in a shortage of labor that will likely continue.”

Lǐ Qīnghuān 李清欢, another deliveryman based in Beijing, told The China Project in December that 70% to 80% of his colleagues fell sick when the city was battling its first wave of infections after loosening almost all virus-control curbs. An employee at SF Express, one of the leading delivery service providers in China, revealed to media in mid-December that there were approximately 18,000 deliverymen in Beijing, but 7,000 to 8,000 were unable to work at the time due to illness.

Complicating the matter was an uptick in delivery usage in December. In the first two weeks of December, there were more than 4.3 billion deliveries to be processed, an increase of 3.5% from last year, according to statistics published by the State Post Bureau.

In order to get Beijing’s logistics network back on track, officials overseeing the city’s postal service encouraged several delivery companies to send a total of 2,300 couriers to the capital. The initiative went into effect on December 13.

One source from an express company that took part in the relocation initiative revealed to The China Project that government officials were racing against time to find a solution. “The government had this need [to overcome this problem] and came up with some plans, and we had the ability to do it,” she said. The person added that the government provided free accommodations for 400 of their deliverymen and instructed them to make incentive policies to keep the workers motivated.

This was not the first time China has relocated couriers in a time of crisis. In the spring of last year, when Shanghai was locked down to contain a surging outbreak, Chinese ecommerce giant JD.com sent around 5,000 employees to the financial hub of the country. One source from the company told The China Project that some workers from its delivery force supported both Shanghai and Beijing.

By December 21, JD.com had sent around 2,000 deliverymen to the capital, and they were from 180 cities across 16 provinces. Among them was Xie, who arrived in Beijing on December 15 and documented his predicament in a string of Douyin videos. In a video posted on December 18, Xie shared his work schedule while showing piles of unsorted packages in a warehouse. According to Xie, his day started at 6 a.m. and by the time he filmed the video at 4 p.m., there was still an insurmountable amount of packages waiting to be processed and transited.

The influx of thousands of deliverymen improved the situation in Beijing. On December 17, the number of daily deliveries increased by 13% compared with December 13, reaching 10.84 million. As Beijing’s delivery capacities slowly grew, so did complaints about unequal treatment from people in other areas. “Shandong’s delivery system is also failing. Is there anyone coming to help?” one person wrote on Weibo. “When the capital has trouble, all of the other cities are paralyzed. Which city is not struggling? Why do we still help others when we have our own difficulties?” another person griped.

“When Xinjiang was under lockdown, I could not receive any packages for three months,” a Weibo user wrote. “Twenty of my packages are still stuck somewhere I don’t know.”

At JD.com, the 2,000 delivery men relocated to Beijing only made up 1 percent of its entire delivery force nationwide. According to official data, there were 4 million deliverymen in China in 2020. In theory, the relocation of a few thousand couriers in December shouldn’t affect the delivery systems outside Beijing that much. But for non-Beijing residents, the eruption of outrage was actually the outcome of long-simmering discontent over the capital’s privileged position. For example, just as the relocation of couriers took place, hundreds of medical professionals from Eastern China were also sent to Beijing to help battle the outbreak.

On Weibo and lifestyle app Xiaohongshu, some Beijing residents said that they had been lambasted and blamed online for the delays of deliveries in other cities. Many critics linked the shortage of couriers in Beijing to its 2017 crackdown on unlicensed buildings that many migrant workers called home. After a fatal fire caused 17 deaths in Daxing District, the Beijing government has been demolishing developments it saw as unsafe, forcing tenants to leave on short notice in the past few years. Unable to find affordable residency, many migrant workers left the city and returned to their hometowns.

For those who agreed to move to Beijing temporarily in December, financial benefits were the main motivation. An employee of JD.com’s logistics department told The China Project that when the couriers arrived in Beijing, their unfamiliarity with the city affected their efficiency and consequently their incomes. To ensure their satisfaction on the job, the company provided salary protection and subsidies for them. “The overall salary they get is usually higher than they can get in their hometown,” the person said, adding that the experience would also give them a leg up should someone wish to get promoted in the future.

A Beijing deliveryman working for YTO Express heard that couriers relocated by JD.com could earn 5 yuan (0.74) for each delivery, more than double the normal payment. “It’s for the money,” the delivery man told The China Project. “If there is no benefit, who will come?”

Those who were enticed by the incentives had to endure grueling working conditions. Many of them reportedly had to work up to 14 hours a day. In Xie’s videos, he said his hands were frequently shaking while delivering packages due to the cold weather in Beijing. In one video, after a medicine delivery, Xie is seen drinking baijiu, his face flushed red from a lack of tolerance. “I heard drinking baijiu could kill the virus, so now I am drinking it,” he said. “If I don’t get COVID, it means this theory is true.”

By December 22, nine days after the arrival of the first batch of JD.com’s relocated couriers, the backlog of its deliveries in Beijing was nearly cleared, according to a source from the company. Since then, most of the deliverymen have left the city. “Some of them went back to their previous job positions, and some of them went to support other cities in their regions that needed support,” the person told The China Project. By the Lunar New Year holiday, Beijing’s delivery system had returned to normal. The location of Xie’s Douyin IP address has changed from Beijing to Yunnan.

“The pandemic made more and more Chinese people realize one thing,” a comment on Weibo read. “It is that the so-called ‘low-end population’ like couriers and sanitation workers actually are very important. Their importance and contributions to society are no less than those of white collars and gold collars. If a city does not have people like them, it will get paralyzed immediately.”