This Week in China’s History: June 9, 1938

The Second World War set new standards in almost every category of human suffering or injustice. But even in the context of those dark times, a single event that was responsible for more than half a million deaths and the dislocation of many millions more stands out. Even more remarkably, this was not a result of perversions of industrialization or new technologies with unanticipated consequences, but rather, in the words of historian Diana Lary, by “great numbers of soldiers [working] with spades, picks, hoes, drill, and hammers.” By the time they were done, the Yellow River, China’s second longest, began flowing out of its banks and down across the plain.

It had taken three tries to spring the river from its course. A first attempt, starting on June 4, blasted a hole in the levee with dynamite, but planners had unknowingly chosen one of the strongest points in the entire levee system, and the gap was too small, and too high, to allow the river to flow out. A second attempt, on June 7, blasted another hole in the riverbank, but this time in the wrong channel, leaving the main watercourse flowing unimpeded. It was the third try, using the pickaxes and shovels of the Nationalist army, that finally released the river.

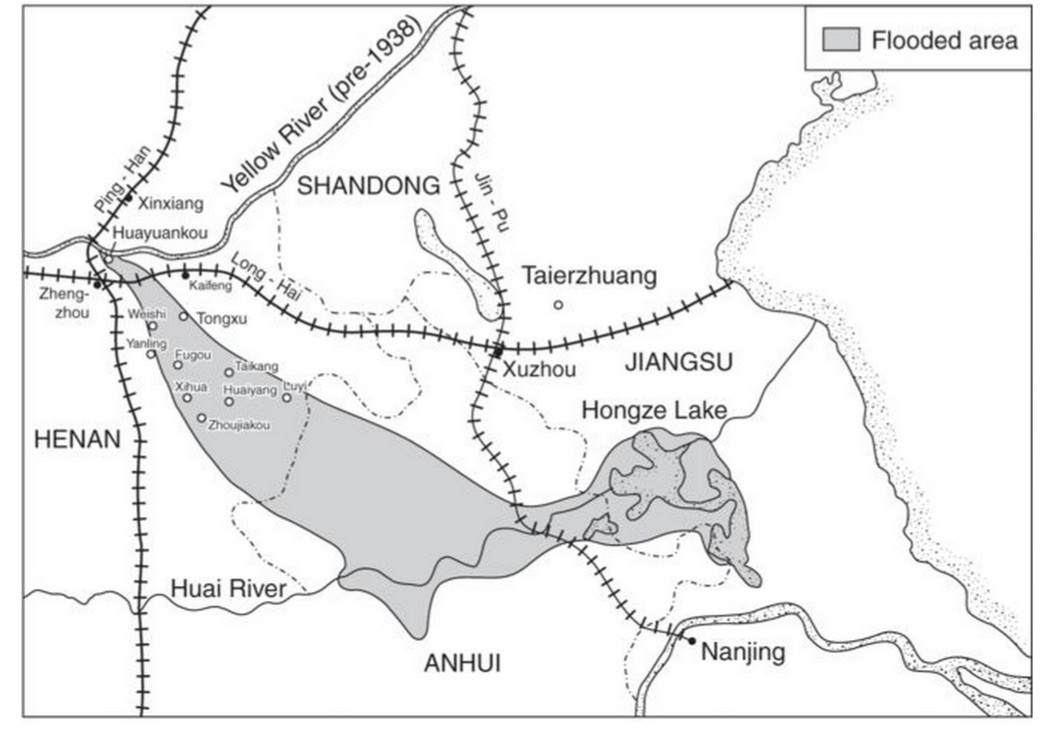

“Once unleashed,” writes Micah Muscolino in his field-defining book The Ecology of War in China, the river “flowed unimpeded across eastern Henan’s landscape…Advancing at a steady rate of around [10 miles] per day, floods spread into narrow, shallow beds of rivers and streams that flowed toward the Huai. Floodwaters filled these waterways and broke their embankments, causing them to overflow and inundate fields to the east and west.”

Within weeks, the floodwaters surged into the Huai River, and then Hongze Lake, overflowing its banks. Seasonal rains augmented the disaster, falling steadily throughout July and August. “At this point,” Muscolino writes, “the scale of destruction went uncalculated.”

The Yellow River originates in the Qinghai plateau, across Inner Mongolia and then northern China. It takes its name from the color imparted to it by the fine loess soil that joins the flow as it crosses Shaanxi and Gansu. (Proving the point, in Mongolian the river was long known as the Black River, reflecting the clarity of the water before it crosses the loess plateau).

Along with its key role as one of the cradles of Chinese civilization, the Yellow River is perhaps best known as “China’s Sorrow”: a source of unpredictable and often catastrophic flooding. One component of this is the river’s tendency to change course — the result of silt raising the riverbed until the water surges over the top of the ever-higher levees — as it crosses the plains of Henan, shifting between a northern channel that flows into the Bohai Gulf and a southern course that terminates in the East China Sea. An 1855 change in course may have killed a quarter of a million people. Floods in 1887 were even more devastating, killing twice that many.

What distinguished the 1938 floods from those earlier episodes, as well as from the 1931 floods, which were centered on the Huai River, was their origin. The floods of 1938 were caused deliberately.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

After the Marco Polo Bridge Incident of July 1937, Japanese armies spread south and west from Beijing, occupying major coastal cities and preparing to move inland. Shanghai fell in the fall of 1937, as did the Nationalist capital, Nanjing, where the Japanese army brutalized the population.

From Nanjing, the Japanese armies attacked Xuzhou, Kaifeng, and Zhengzhou, a quick rail journey from Wuhan, where the Nationalist government had relocated its capital. If Wuhan fell, Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石 Jiǎng Jièshí) might have no choice but to surrender.

The idea of intentionally breaching the Yellow River levees is often attributed to a German advisor, Alexander von Falkenhausen, but he was just one of many, and the decision to use the river to stymie the Japanese advance was endorsed and proposed by Chinese commanders and planners. Some hoped that the floodwaters would destroy the Japanese forces, but in any event the flood would slow their advance by destroying the critical railway, giving the Nationalists time to evacuate Wuhan. When Xuzhou fell, leaving little between the Japanese armies and Wuhan, Chiang approved the plan to unleash the river.

Discussions among Nationalist leaders make clear that they were both aware of the destruction the floods would cause, among both the Japanese military and the Chinese civilian populations, and their belief that this was a necessary sacrifice. “It is clearly known that the sacrifice will be great,” Muscolino quotes KMT commanders, “but with the urgent need to save the nation the pain must be endured.”

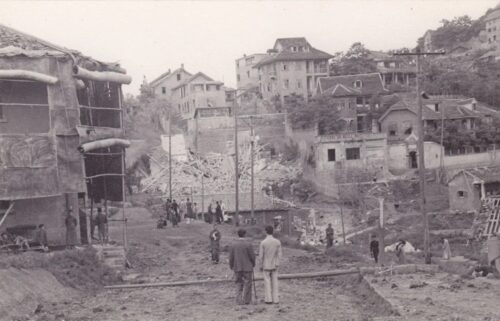

The breach of the dykes was successful in the short term, cutting the railroad and delaying the Japanese advance. The delay enabled the KMT government and armies to evacuate Wuhan, relocating to Chongqing, a thousand miles up the Yangtze.

But the cost of this short-term military success was borne not by Nationalist leaders, but by China’s civilian population. A warning might have given civilians a chance to escape the path of the floods, but wanting to maintain the secrecy of the plan, KMT officials provided only minimal notice. In fact — perhaps betraying a sense of guilt — as soon as the levee was broken, KMT leadership began an information campaign blaming Japanese bombs for the breach. Propaganda filmmakers staged the breaching of the levees by Japanese bombs. Ironically, Lary writes, the staged sabotage “was the only time at which explosives were actually used.” Chinese soldiers were filmed attempting to stop the floods and “local people were drafted in to give the semblance of mass participation in ‘closing’ the dyke.” The Nationalists brought foreign journalists to photograph and report on the breaching, going so far as to cite the floods as another example of Japanese atrocities, even though they had been caused by the Chinese government itself. The Japanese, however, quickly pushed back and demonstrated that this was not true; the narrative quickly shifted from an atrocity perpetrated by a foreign enemy to a necessary sacrifice.

The strategic benefits of the floods were temporary. Wuhan fell to Japanese forces within a few months, although the time gained did enable the Nationalists to continue the fight. By that measure, it may be that the actions were justified, from a military standpoint.

Nonetheless, the cost was devastating. The river continued to flood across the plain throughout the war, and the breach that Chiang’s armies had opened was not closed until March of 1947.

Historians, including Lary, Muscolino, and Kathryn Edgerton-Tarpley, have pointed to the intentional flooding as part of a complex and profound moral shift in how the Chinese government defines the nation’s survival, from a traditional focus on the people’s welfare as paramount to a more abstract concern with national defense and security. Edgerton-Tarpley in particular, in a 2014 article in the Journal of Asian Studies, compares the responses to the 1876 Henan famine, with the decision to intentionally cause one catastrophe in hopes of reducing another, perhaps the ultimate example of “destroying the village in order to save it.”

The decision to flood the Yellow River may, or may not, have been justified. Much depends on what basis we use to evaluate it, but it is unquestionably an example of the kinds of moral debates — with dire consequences, regardless of the decision — that defined much of World War II.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.