China’s increasing influence in Myanmar’s civil war

Analysts warn that Beijing is gaining leverage in Myanmar, backing the junta and no longer actively urging the regime to return the country to its democratic transition. This doesn't come without risks, however.

China has emerged as the most powerful outside force in Myanmar’s spiraling crisis, embracing the military regime just as the generals are losing control over swathes of the country while also building its clout over several ethnic armed groups on their joint borders.

Chinese Foreign Minister Qín Gāng 秦刚 made his first official tour to Myanmar last month, meeting the junta’s Senior General Min Aung Hlaing in Naypyidaw. Beijing also convened peace talks between ethnic resistance organizations (EROs) and the junta. The military’s proxy Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), meanwhile, visited Yunnan Province.

Analysts warn that Beijing has gained substantial leverage over Myanmar’s embattled regime and several armed actors along the porous borders. For more than two years, the junta has relied on Chinese and Russian fighter jets and arms to kill, airstrike, and gun down civilians and the resistance across the country.

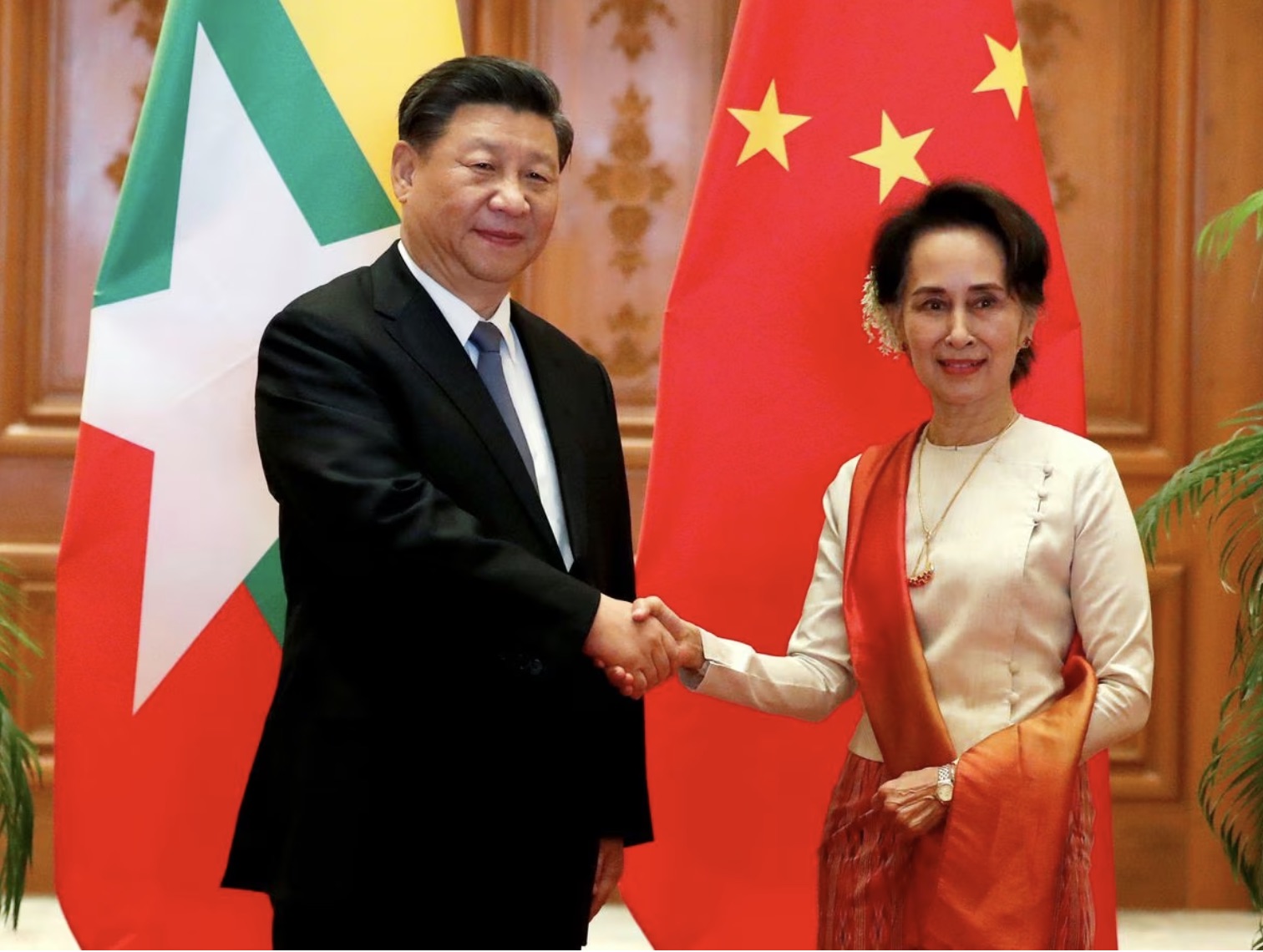

In recent months, China has stopped actively urging the regime to return Myanmar to its democratic transition, or voicing support for detained leader Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy (NLD) party. It has continued to cold-shoulder the underground National Unity Government (NUG), a parallel government set up by elected and ousted lawmakers primarily from the NLD.

This, however, is not without risks, experts and diplomats warn. The Burmese generals have effective control over less than half the country, according to some estimates, and efforts to bring them to the negotiating table with the ethnic armies have yet to produce results. Beijing’s support also shields the junta from international pressure to back down, and prolongs the civil war that puts Chinese strategic ambitions at risk.

But the Chinese leaders likely do not see it that way. By throwing its weight behind the junta and ethnic armies, China seeks to ensure that Myanmar’s fragmentation — similar to China’s historical “Seven Warring States” period over 2,200 years ago, to quote one veteran Burmese analyst — will fend off any considerable Western presence.

China’s growing influence

Beijing’s growing clout in Myanmar, a country larger than France and sandwiched between India, China, and Southeast Asia, has massive geopolitical implications for the region. The junta plans to give Beijing access to the Indian Ocean through a proposed Chinese-led deep-sea port in western Myanmar, and railway and highways linking the port to Yunnan through northern Myanmar.

The Burmese military has also explicitly backed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China’s claim over Taiwan. This may shift the balance of power in Southeast Asia, where the U.S. and China have been competing for influence.

Beijing’s position has to do with domestic politics, after President Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 centralized decision making and sidelined the foreign affairs ministry, said China expert and former diplomat Michael Ng.

“In the same month [March] that he secured a convention-breaking third term, Xi paid a state visit to Moscow even as Russia continues to bomb and pillage Ukraine,” said Ng, a former Hong Kong government official in charge of Southeast Asian affairs. “It is a clear sign that Xi is doubling down on authoritarian regimes around the world as long as they support his ambitions. It isn’t too surprising that Xi extended support to Min Aung Hlaing by sending Qin Gang to Myanmar.”

China had supported the leading role of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in resolving the Myanmar crisis, but later decided to bypass the bloc and initiate its own maneuvers because of ASEAN’s inertia, Ng told The China Project. “In May, Qin Gang ‘downgraded’ the coup from an international or regional issue to internal affairs, and stopped talking about ASEAN’s role in Myanmar,” he noted.

Min Aung Hlaing’s regime has been pushing for Chinese investments to resume, several Chinese sources told The China Project. Chinese investments top approved foreign direct investments under the Myanmar junta, which stopped publishing details of the investment approvals.

“China is now backing the junta,” a diplomat in Yangon commented, referring to the active engagement between the regime and the Chinese government.

The key question, the diplomat said, is how the regime may accommodate China’s economic and strategic ambitions in Myanmar, including the proposed port, dams, and roads.

A decade of reformist governments under Thein Sein and then Aung San Suu Kyi sought to ensure mega infrastructure proposals aligned with Myanmar’s economic and environmental interests, but the junta has neither the capacity nor the political muscle to do so.

“How far will the Burmese generals allow China to dictate the terms? This is a question relevant to the geopolitics in the broader region and the Indo-Pacific,” the diplomat said, adding that there’s also the question of how much Beijing can achieve with this strategy of backing the regime and ethnic armies, given the chaos in Myanmar and the suspicion of Burmese generals toward their giant neighbor.

Recent Sino-Burmese relations

China had long viewed Myanmar under previous military-run regimes as its backyard, but felt sidelined when then president Thein Sein opened up the country in 2011 and initiated a process that brought about limited democratic reforms in the formerly isolated country. It was Thein Sein’s quasi-military government that suspended China’s much-prized Myitsone Dam project located in northern Kachin State, to the chagrin of Beijing. None other than Xi, then China’s vice president, officiated the ground-breaking ceremony of this dam in 2009.

Chinese officials were seen by Western governments and pro-democracy supporters in Myanmar as unduly concerned about U.S. influence in the country, and were pressuring ethnic communities not to engage with the U.S.

“When I was in Myanmar, my Chinese counterpart suggested I not visit Kachin, as it was sensitive,” said Scot Marciel, who was the U.S. ambassador to ASEAN, Indonesia, and Myanmar. “I took it to mean China considers Kachin in its backyard.”

In 2018, when Marciel traveled to Kachin, then Chinese ambassador Hóng Liàng 洪亮 flew there the next week, warning local communities not to engage with the U.S. and demanding their support for Myitsone. Hong’s threatening warnings were taken poorly in Kachin, and the attendees went public with the meeting.

“How far will the Burmese generals allow China to dictate the terms? This is a question relevant to the geopolitics in the broader region and the Indo-Pacific.”

Beijing’s unchallenged influence in Myanmar — primarily because the U.S., Japan, and Southeast Asian governments are paralyzed about what to do — is a far cry from the time China got denounced across Myanmar for not joining worldwide condemnations against the coup.

The military’s party got platformed in China recently. USDP’s visit to a Yunnan university in mid-March took place at around the time the NLD and major political parties — which collectively won 89% of seats in the 2020 general elections — were dissolved by the junta by force.

The USDP delegation was led by Lin Zaw Tun, a former military colonel allegedly involved in the assassination of Ko Ni in 2017. Ko Ni, a Muslim lawyer who’s also a Supreme Court Advocate and one of Suu Kyi’s top legal advisers, was shot in the head at point-blank range outside Yangon International Airport in what Yanghee Lee, then the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, branded as “another shocking example of a reprisal against those speaking out on behalf of the rights of others.”

The NUG leadership said they were “horrified” by the USDP’s visit to Yunnan, but “sadly not surprised” by China’s hugging of the Burmese generals.

“Although it is evident that a stable Myanmar is in China’s interest, China clearly prefers Myanmar under an oppressive and isolationist military regime,” said Minister Dr. Sasa, a cabinet minister of the NUG and an NLD member close to Suu Kyi.

Referring to Myanmar’s resources and strategic location for China, Sasa said, “Beijing is betting that by supporting the junta, they can secure unfettered opportunities to expand their political, military, and economic interests into Myanmar. This thinking betrays a poor understanding of the Tatmadaw, whose core ethos is betrayal and selfish exploitation.”

“Tilting the balance of power”

Beijing is keen for Myanmar’s junta to prove that they are a credible governing force, according to diplomats and analysts. To that end, China has pushed for peace talks among Myanmar’s warring states.

China recently sponsored talks in the Mongla region in northern Myanmar’s Shan state, near China’s Yunnan Province, between the junta and three of Myanmar’s ethnic army coalition, known as the Northern Brotherhood Alliance. According to VOA, the talks were aimed at convincing the ethnic armies to support the junta’s planned polls, but collapsed without an agreement on June 2. Mongla is a Chinese-speaking region controlled by a rebel group.

The attendees — the Arakan Army (AA), the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) — have been supporting the anti-coup movement by providing military training and supplies. (The three most important ethnic groups currently fighting the junta — the Kachin Independence Army, the Karen and Karenni forces — were absent from the talks and are continuing their fight.)

“China’s top priority in Myanmar is to gain access to the Indian Ocean through the proposed port in Kyaukphyu and connectivity from Rakhine to Yunnan.”

China has effectively abandoned the NLD and Suu Kyi, and instead openly strengthened relations with the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC), which is the largest negotiating body of ethnic armies, said Jason Tower of the United States Institute of Peace.

According to Tower, Beijing is giving high levels of political, economic, and tactical military support to the United Wa State Army, a powerful Chinese-speaking militia group controlling territory in northern Shan State that nominally pledges loyalty to Myanmar’s sovereignty.

By doing so, China is “tilting the balance of power in favor of the Wa and supporting consolidation of the critical northern EAOs under UWSA leadership,” Tower told the China Project. “Beijing is using the relations with the northern armed groups to pressure the junta and vice versa, and in practice has abandoned its support for ASEAN’s leading role in the Myanmar crisis.”

Sources involved with the Chinese insist, however, that Beijing was merely dealing with whoever’s in power.

“A few months ago China moved to fully engage with the State Administration Council (also known as SAC, the official name of the junta) after keeping some distance with the Burmese generals since the coup,” a source close to Chinese government officials said. “The engagement has resumed but the results haven’t.”

“China’s top priority in Myanmar is to gain access to the Indian Ocean through the proposed port in Kyaukphyu and connectivity from Rakhine to Yunnan,” the source added. “Chinese officials are aware how unpopular the SAC is and how much support Aung San Suu Kyi has. But Daw Suu went too far in trying to eliminate the Burmese military.”

Many will challenge this assessment. Suu Kyi reached a compromise with the generals more than a decade ago and took part in the system under the military-drafted constitution, which barred her from being the president and gave the military a huge role in government and parliament.

China’s hopes for the future of Myanmar

The Burmese junta has moved to align with Xi’s core interests, backing China’s claims over Taiwan in a joint statement. The military’s proxy USDP also accused then U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi of destabilizing East Asia with her visit to Taiwan.

“On China-Myanmar relations, we started to see a notable change in China’s approach from December 2022, around the time when Beijing decided to end its draconian COVID control measures. This was also after Xi’s consolidation of power and the new emphasis on the Global Security Initiative,” said Laetitia van den Assum, formerly the Dutch ambassador to Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia.

In particular, China appears concerned about U.S. support for the resistance and NUG, and the U.S. Burma Act, according to various government sources. Last December, U.S. President Biden signed into law the Burma Act as part of the 2023 National Defense Authorization Act, which pledged non-lethal assistance to Myanmar’s resistance.

“Although it is evident that a stable Myanmar is in China’s interest, China clearly prefers Myanmar under an oppressive and isolationist military regime.”

Marciel said Beijing saw the Burma Act as a sign that the U.S. was more actively supporting the resistance and that a resistance victory could therefore increase U.S. influence at China’s expense. It’s plausible that the Chinese government stepped up pressure on northern ethnic armies to cut a deal with the junta as a response, he added.

“China has given the junta greater recognition and legitimacy, and it has continuously emphasized the importance of the 2008 constitution. It looks like the NLD and Aung San Suu Kyi have been written off,” said van den Assum. “If China assumed that the SAC would emerge victorious from its fight against the broad-based resistance movement and that peace talks with the junta stand a chance, it might have to think again. Anti-China sentiments around the country are already rising.”

The NUG has told the network of anti-coup resistance forces not to attack Chinese investments, but the sentiment might change as Beijing doubles down on its support for the junta.

Meanwhile, the generals have relied on Chinese investors to revive the energy sector. But even Chinese companies appear to stay clear of making long-term commitments.

“Before the coup, public and private companies from China and elsewhere were interested in long-term projects, like building and operating a solar plant for 20 years,” said Guillaume de Langre, an energy expert who advised Myanmar’s civilian government until 2020. “Now they focus on short-term supplier deals, like delivering a turbine or an inverter. It’s less risky, because they can leave at any time, and it doesn’t require long-term trust in the SAC.”

For the NUG, which commands huge influence over the Myanmar population, the message to Xi is that the Burmese generals are bad for China.

“Chinese foreign policy prioritizes Chinese interests, and we cannot fault Beijing for this, but President Xi must understand that Chinese interests cannot be served by partnering with the Myanmar military,” Minister Sasa said.