Shadow reserves — how China hides trillions of dollars of hard currency

China has a lot of foreign exchange reserves that do not show up in the official books of the People’s Bank of China. Those funds have been hidden in the state banks, and largely escaped scrutiny.

China is so big that how it manages its economy and currency matters enormously to the world. Yet over time the way it manages its currency and its foreign exchange reserves has become much less transparent – creating new kinds of risks for the global economy.

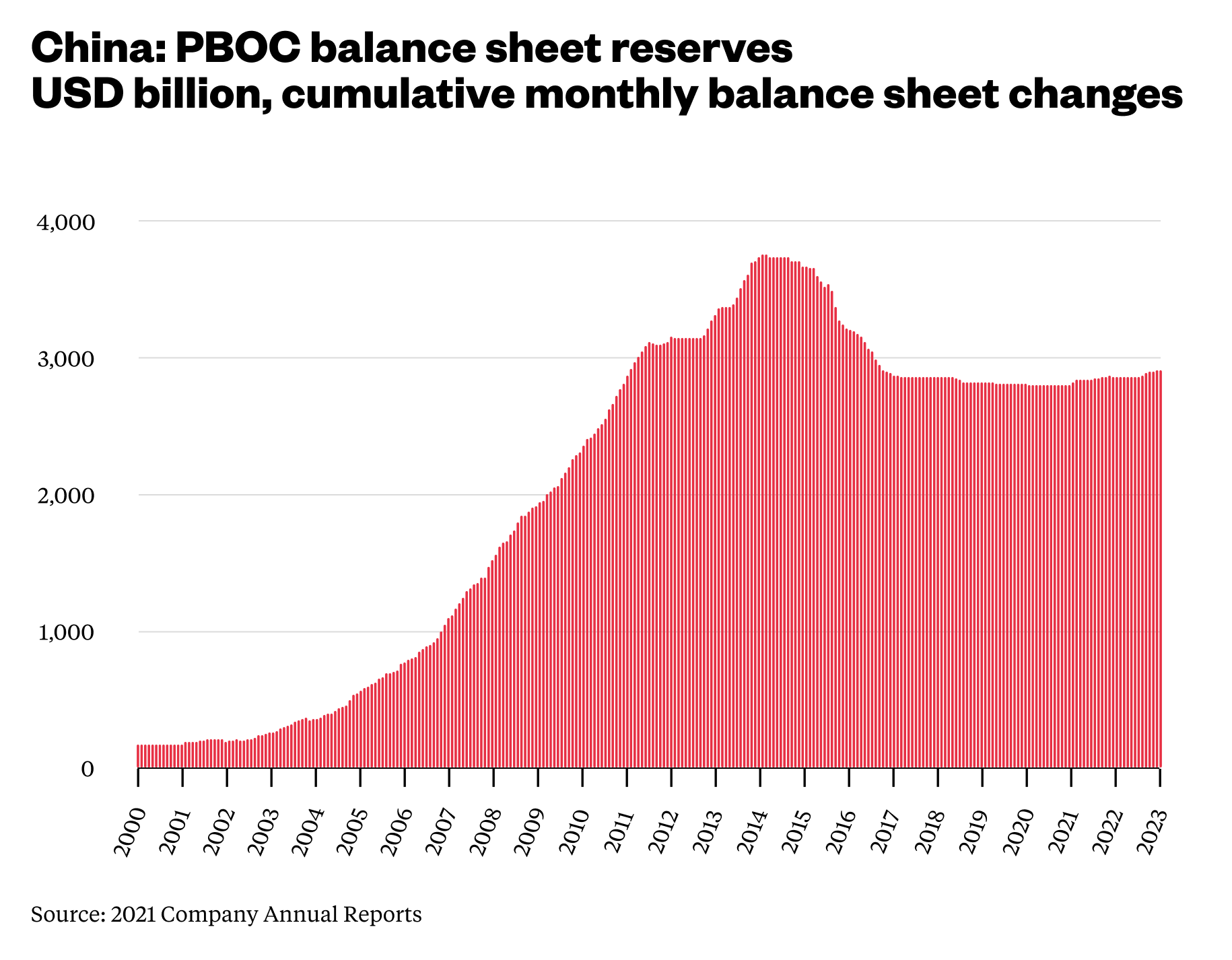

From 2002 to 2012, China’s central bank was active in the currency market almost every day — usually buying dollars to keep China’s currency from rising, and to make sure China’s exports stayed cheap.

During this period, China’s foreign exchange reserves steadily increased. So did China’s holdings of Treasuries and the bonds issued by Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae— the two major types of “Agency” bonds that are implicitly backed by the U.S. federal government. Economists worried that China’s intervention in the currency market was keeping trade unbalanced; foreign policy gurus worried that China might sell bonds in a moment of geopolitical tension, turning a security crisis into a financial crisis.

Poof!

But a funny thing happened sometime over the last ten years: China’s reserves stopped rising. Sure, the number reported by the foreign exchange authorities bounces around a bit, as the market value of China’s long-term bonds and euros sambas with global markets. But the foreign exchange reserves reported by the central bank (the People’s Bank of China or PBoC), which accounts for its reserves on its balance sheet at their historical purchase price, has been constant.

The stability of China’s reported reserves is a real puzzle. Despite all the talk of deglobalization, China’s export surplus is actually at an all time high. China’s true current account surplus is likely larger than the $400 billion that China now officially reports. And currency traders know that China’s currency bounces around a lot less than other big currencies — the yuan doesn’t act like a currency that is tightly pegged to the dollar anymore, but it doesn’t act like a freely floating currency either.

So what is going on?

Just as China has “shadow banks” — financial institutions that act like banks and take the kind of risks that a bank might normally take but aren’t regulated like banks — China has what might be called “shadow reserves.” Not everything that China does in the market now shows up in the PBoC’s balance sheet.

China’s lack of transparency here is a bit of a problem for the world. China structurally is so central to the global economy that anything it does, seen or unseen, will eventually have an enormous impact on the rest of the world. China’s enormous purchases of U.S. Agency bonds before the global financial crisis pushed private investors into riskier mortgage backed securities, helping to create the conditions that gave rise to the 2008 shock.

China’s post-crisis push to diversify its reserves helped give rise to the Belt and Road Initiative, which started as a new way for the policy banks to help Beijing put its ever-accumulating foreign exchange to use before a genuine strategic purpose was grafted on to it. More recently, China’s state banks have become a big source of dollars for their global peers — including, rather strangely, Japanese institutions looking to juice their returns in the dollar bond market.

So, while exchange reserves may seemingly be of interest only to economists, their management and use can have enormous real-world effects. They are powerful enough of an economic force such that an entire, global, decades-long infrastructure plan was, in some ways, just a side effect of a 2009 decision to find new ways to manage China’s foreign exchange.

So how can a country make its foreign exchange reserves disappear?

One way is to set up a sovereign wealth fund — the central bank basically sells its foreign exchange to a specialized government agency that has a mandate to invest in risky (non-reserve) assets. China of course did so, setting up the China Investment Corporation (CIC) back in 2007. But CIC got burned on a couple of its initial investments and actually didn’t use the bulk of the $120 billion it raised to buy foreign exchange off the books of the PBoC until 2009 or 2010.

The main way China has hid its reserves has been its big state banking system. For much of the early history of the People’s Republic, there wasn’t much of a distinction between the central bank and the state banks — they were all just part of the government. The Bank of China, whose iconic I.M. Pei designed tower helps define the Hong Kong skyline, was the de facto central bank of the early Chinese Republic, and was China’s only foreign exchange bank in the early days of the People’s Republic. As recently as the 1990s, it helped manage a portion of the government’s formal reserves — and it is rumored to still occasionally act in the market on the government’s behalf.

Step 1: Put the money in state commercial banks

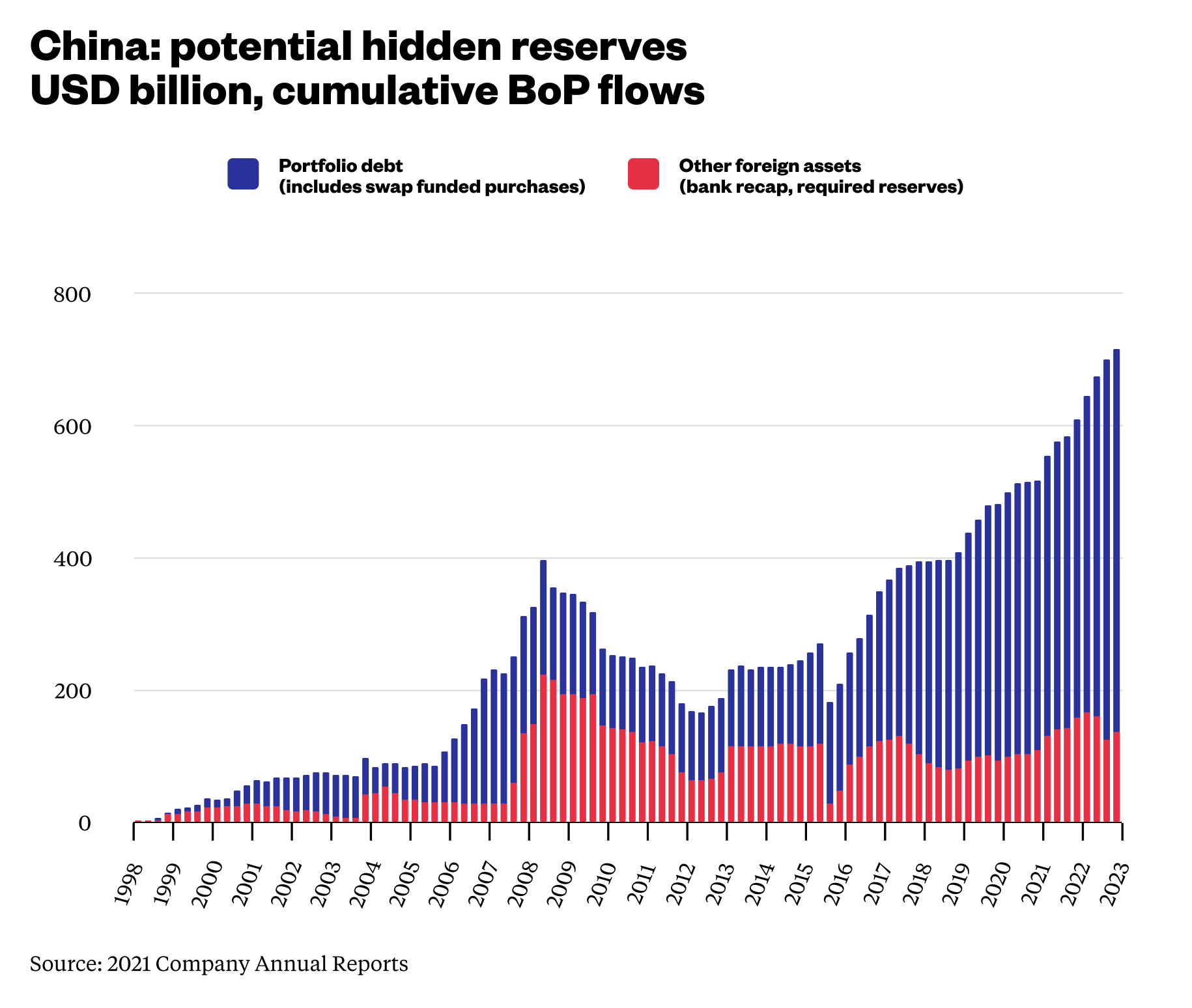

There is actually a well-documented money trail between the PBoC and the state commercial banks in the years between 2003 and 2008 — though this history is now often forgotten. (The major state commercial banks are the Bank of China, Industrial & Commercial Bank of China or ICBC, China Construction Bank,and the Agricultural Bank of China.)

Back in 2003, China used $45 billion of its reserves — a big sum at the time — to recapitalize the Bank of China and China Construction Bank. ICBC, one of the other four major state-owned banks, got $15 billion in 2005. The banks took over the management of $45 billion of China’s reserves — the reserves were never sold, they were just handed over to the bank — and China’s central bank got equity in the banks in exchange.

The PBoC also moved about $150 billion over to the state commercial banks in late 2005 and calendar 2006. It did so by swapping dollars for the yuan held by the banks. Doing this as a swap rather than a loan had some technical advantages for the central bank — and it kept the transaction off the PBoC’s formal balance sheet. The dollars shifted into the banks were invested in foreign bonds (holdings of foreign bonds by “private” investors in China went from around $50 billion to close to $200 billion). The entire transaction is all visible in the banking data if you know exactly where to look.

Finally, in 2007 and 2008, the PBoC more or less forced the banks to hold $200 billion of their required reserves in dollars even though the banks at the time didn’t have many dollar deposits. This too can be tracked: the banks’ foreign currency reserves appeared on the PBOC’s balance sheet as “other foreign assets.”

All told, by the end of 2008 China’s government had about $400 billion in “hidden” reserves — small by today’s standards, but a sum then equal to about 10% of China’s GDP.

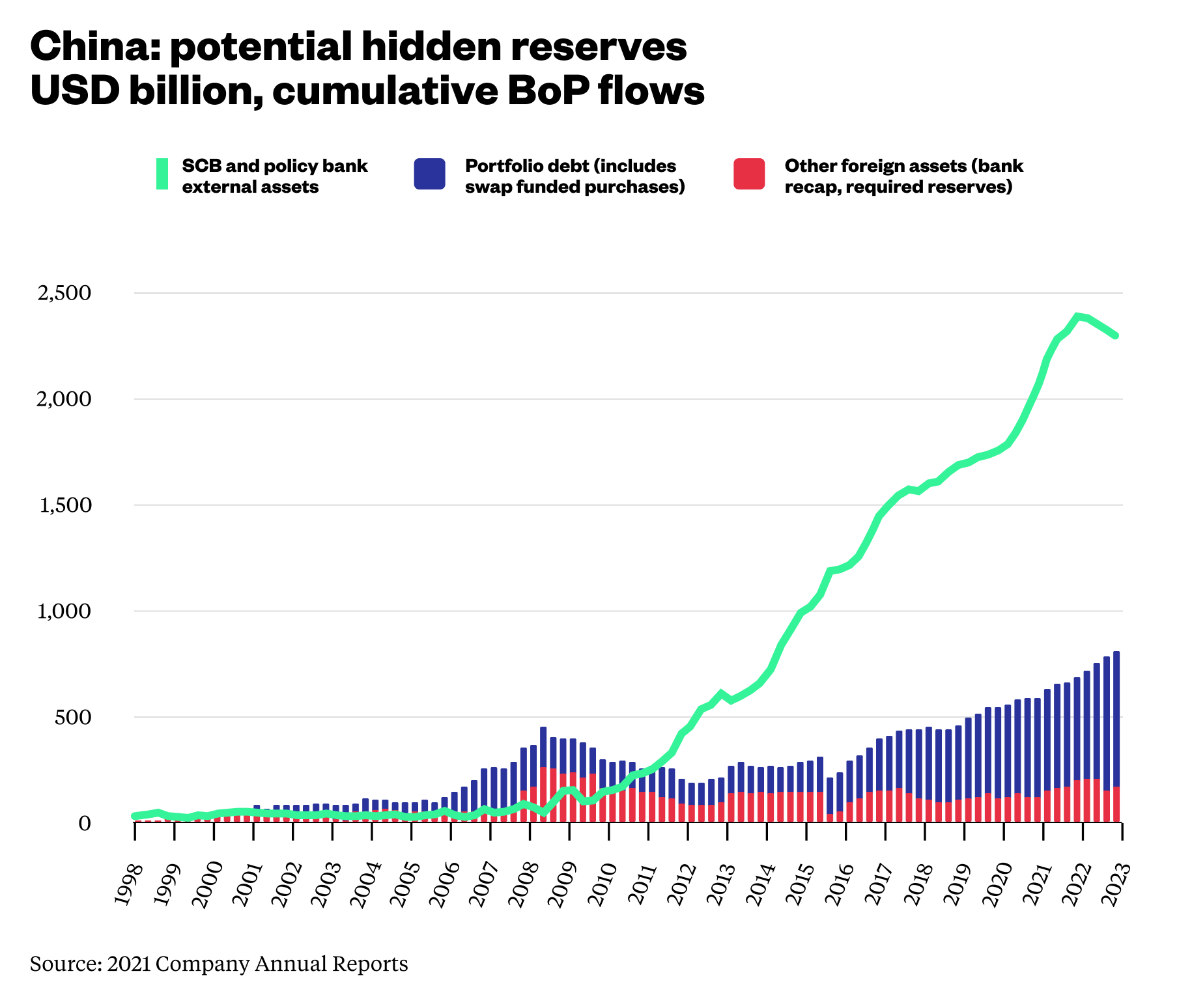

Step 2: Put the money in policy banks

After the global financial crisis of 2008-2009, China settled on a new strategy for making use of its excess foreign exchange reserves: handing a portion of its foreign exchange to the big policy banks — the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China — so that they could lend to support China’s ballooning overseas investment.

One of the first signs of this policy shift came when the China Development Bank started to lend huge sums to support an increase in global oil output to help meet the needs of China’s growing economy. Scholar Erica Downs noted back in 2011: “Since 2009, China Development Bank has extended lines of credit totaling almost $75 billion to national energy companies and government entities in Brazil, Ecuador, Russia, Turkmenistan and Venezuela.” Russia’s state oil company for example got a $15 billion loan to expand production in the far east, and Russia’s oil pipeline company got $10 billion to build a pipeline to bring the oil to market. Venezuela got at least $30 billion. Angola got over $20 billion.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

The CDB and the Export-Import Bank of China also lent big sums to countries looking to buy Chinese telecommunications equipment. That helped drive the global expansion of firms like Huawei, which has a credit line of at least $30 billion with the CDB. Work by Aid Data and the World Bank documents how the Export-Import Bank of China also ramped up its support for road, dam and powerplant construction across the world.

All this is well known by now. It was institutionalized in 2013 with the formal launch of Xí Jìnpíng’s 习近平 Belt and Road Initiative.

What isn’t as well known is that the policy bank’s overseas lending also served, in effect, to hide some of China’s reserves. When China’s reserve manager, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), lends money to CDB or the Export-Import Bank of China, those funds are — correctly — no longer counted as part of China’s official reserves.

However, the money trail through the policy banks is much harder to follow than the pre-global crisis money trail to the state commercial banks.

The first signs appeared back in 2010, when reports emerged that the CDB and the Export-Import bank of China were making “entrusted loans” on behalf of the State Administration of Foreign Exchange. Caixin reported:

The State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE)… has taken initial steps toward giving policy and commercial banks authority to handle loans for intergovernmental cooperation projects. The reforms also expanded SAFE’s responsibilities beyond its traditional role of managing foreign exchange reserves, effectively turning the agency into a foreign-currency lender. The new forex direction dates from the end of last year, when the State Council asked SAFE to take the lead in projects, including a Chinese loan-for-Russian-oil exchange deal. The agency was also told to study additional innovations for policy lending.

The policy banks initially weren’t totally happy about the initial financial set up for “entrusted loans” — they got a fee for managing SAFE’s money when they would rather have taken in a deposit from SAFE and then made the loan on their own balance sheet. The scale of these entrusted loans has never been transparently disclosed, but there are hints that it is big. Back in 2015, for example SAFE converted $93 billion ($45 billion for Exim, $48 billion for CDB) of entrusted loans were converted into equity in the policy banks.

The PBoC also contributed to a set of opaque funds that help the policy banks out. SAFE supplied 65% (over $25 billion) to the $40 billion Silk Road Fund. SAFE supplied 80% of the “initial” $10 billion of the China-Africa Fund for Industrial Cooperation (CAFIC) and 85% of the $30 billion for the China-Latin America Cooperation Fund (a.k.a. China-LAC Cooperation Fund). SAFE’s 2020 annual report celebrated the “10th Anniversary of the Diversified Use of Foreign Exchange Reserves” by SAFE’s contribution to diversifying China’s reserves by highlighting its “entrusted loans” to “small, medium and large sized financial institutions” and its capital investments in CIC International Co., Ltd. and CNIC Co.

CIC International is of course the Hong Kong branch of China’s sovereign wealth fund; CNIC is a Hong Kong based mining, energy and infrastructure investment company that had an initial capitalization of $11 billion.

Sum it all up and the disclosed funds provided to these initiatives total over $150 billion — and that is likely only the tip of the iceberg. These funds are of course on top of the funds provided through entrusted loans and the conversion of entrusted loans into equity.

These hidden funds, backed with foreign exchange moved out of the reserve holdings of China’s central bank, are likely to be a big reason why China’s reported reserves are stable. It is completely fair not to report these foreign currency assets as part of China’s formal reserves — they aren’t being held in easy to sell, safe foreign assets. But China should separately report all of the foreign currency assets held by the PBoC, including its foreign currency funding of state banks and investment funds.

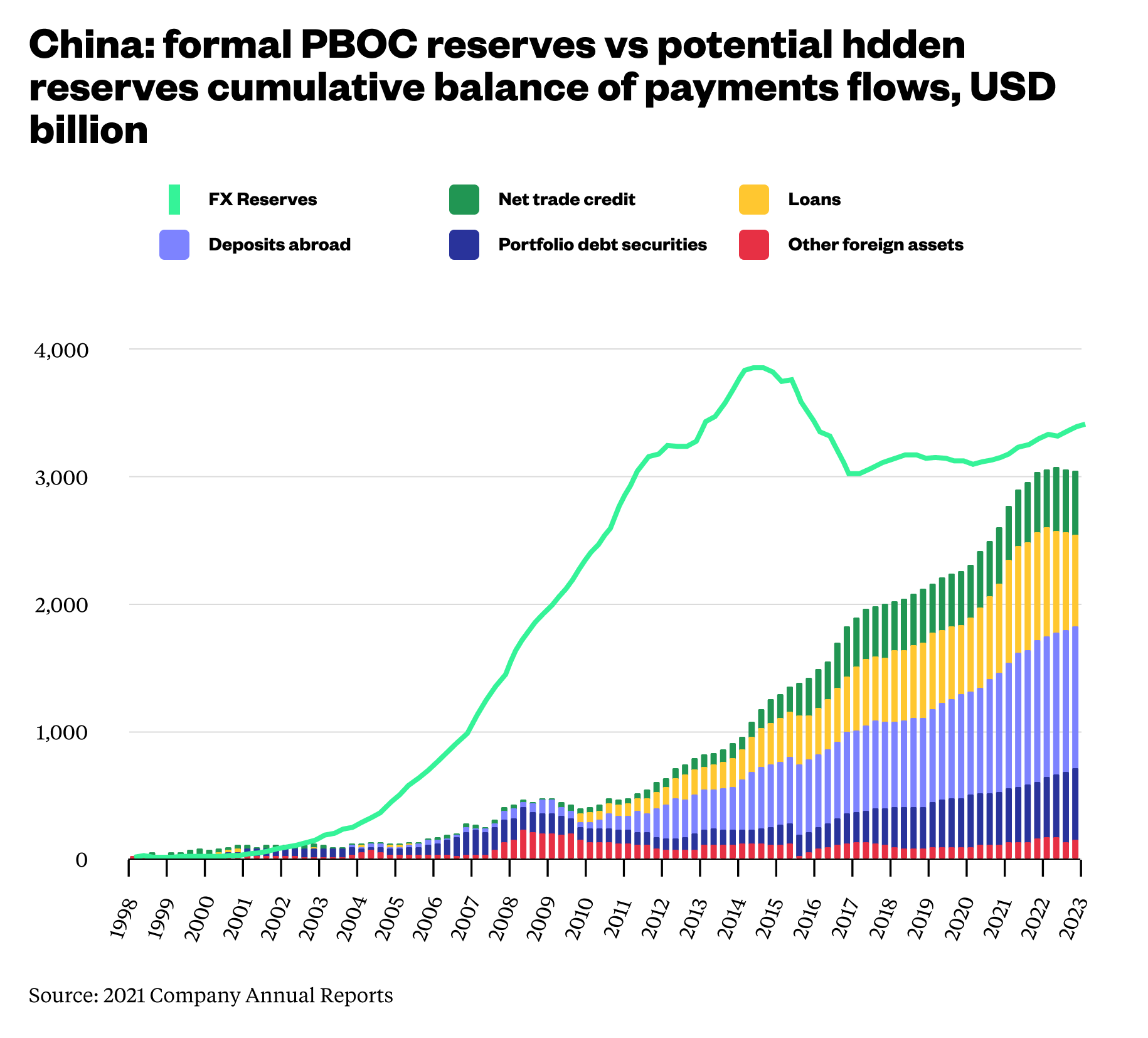

Step 3: Convince the State Commercial Banks To Act Like the PBOC

There is one other important source of hidden reserves — the domestic foreign currency deposits of the state commercial banks. The deposit taking banks, a set of state banks that are separate from the big policy bank, now have over $1.1 trillion in foreign assets. They only have $200 billion in foreign liabilities, so they have about $900 billion in foreign holdings that are funded domestically. Some of these funds historically have come from the State Administration of Foreign Exchange, as noted above (though the accounting for entrusted assets may be complex). But the banks also have taken in more domestic foreign currency deposits than they have lent out domestically in foreign currency, so these domestic deposits — think deposits from the state oil companies and other big state-owned enterprises — are balanced by offshore foreign currency assets.

The strange thing about these deposits is that they don’t act like normal deposits. Dollar deposits rose when dollar interest rates were below the rate on yuan, and recently have slid even though dollar rates now top yuan rates. The net foreign asset position of the state banks looks like the balance sheet of a central bank that is acting in the market to stabilize its currency. Perhaps that is just a coincidence — but I rather doubt it.

A six trillion dollar pile of money?

All told, institutions that report to China’s central government probably have closer to $6 trillion in foreign assets than the $3.12 trillion SAFE reported in December 2022.

This total counts the foreign assets of the state commercial banks (owned by a State Council holding company through the CIC), the state policy banks (owned by the PBoC, with some participation of the Ministry of Finance), and the CIC (owned by the State Council but with some funding from SAFE).

Why should we care?

What does any of this matter?

Well, China is so big an economy – and such an unbalanced economy – that all its activities just have an outsized global impact.

China’s shadow reserves are big. Bigger than the formal reserves of the world’s second largest holder of reserves (Japan). Bigger than the assets of the world’s largest sovereign wealth (Norway, though Singapore would be in close competition if its sovereign fund disclosed its true size). It isn’t a surprise that these massive pools of foreign exchange are at the center of most interesting debates. China’s contribution to global debt distress is a function of the diversion of foreign exchange out of the U.S. bond market and into global infrastructure lending. Yet China’s banks have access to so many dollars that China’s state commercial banks came to play an important role in providing funding to other global banks through cross currency swaps (what the Bank for International Settlements or BIS calls hidden debt) even as the policy banks turned low income countries into their playground. Looking at China’s reported holdings of Treasuries just misses the bulk of China’s global financial presence these days.

The scale of these hidden reserves — foreign current currency assets that aren’t formally counted as “reserves” — also highlights an important fact that is often forgotten amid all the talk of China’s domestic debt problems. Globally China is still a massive creditor, and the weight of China’s massive accumulation of foreign exchange is still felt around the globe.